It was the kid being burned on the cross that did it. Initially I didn't see it in its intended sequence, but on the preview page of The Drifting Classroom’s second volume, an advertisement for what to expect in the next installment.[1] I was sitting in the library, eleven or twelve years old, way younger than the book jacket’s recommended “M” rating suggested I should have been but ironically the exact age demographic this Shonen Sunday serial was originally intended for. That illustration, the stiffness of it, the roar of the fire matched by the cry of the boy, the terror and absurdity and specificity reached out to me and grabbed me in a way that an image can sometimes do without ever letting go. Having not grown up in the kind of household where images of martyrs abound, this was my first proper taste of horror's capacity to turn agony into the sublime.

Ten years since the day I sat in that library, Viz Media announced a reprint of Kazuo Umezz's The Drifting Classroom in three spiffy new hardcovers, sporting larger dimensions and a new translation. For myself, rereading this comic was a uniquely vivid emotional experience, recalling at once the confusion and sadness I often felt at the age I first read it and that giddy pleasure I felt then learning for the first time that stories like this could exist. Although my relationship to this comic is fairly unique, I can’t imagine any new reader being any less gripped. The Drifting Classroom is as fantastic a horror comic as there has ever been, a vivid anxiety attack brimming with unforgettable illustrations.

The Drifting Classroom begins with a child catastrophizing and rapidly shifts to actual catastrophe. Sixth grader Sho Takematsu, just too old for childhood toys he can’t bring himself to let go of, has a fight with his mother that was once memorably described as resembling a lover’s quarrel.[2] Sho runs off to school after accusing his mom of threatening to stab him (she was holding a kitchen knife), turning over in his head from anger at his mother to piddling self critique to a wish for the world to collapse, intermittently distracting himself through panic about whether to get to school on time or run back to get his lunch money.

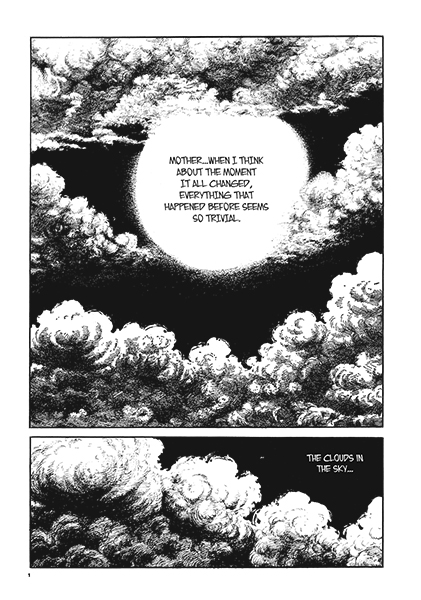

When Sho finally does arrive at school these desperate stresses turn out to be fairly insignificant - most of the other kids also forgot their money. But even so, this panic heralds the end of Sho’s life as he knew it, as a tremor suddenly rocks the school. Unbeknownst to the students, the school itself has vanished, leaving a gaping crater in its place. From within the school, however, it seems that, as Sho proclaims, “Everything outside the school is gone!” The school and nothing but the school stands intact in an endless apocalyptic zone, a mysterious, aesthetically terminal[3] place of complete desolation. Social order constricts and chaos reigns within the school as teachers are picked off like flies, while the outside is a wasteland at once wilderness and trash heap, an oppressive swell of clouds and mud and air which may be poisonous. And incidentally, the food Sho forgot to bring money for is now extremely scarce.

The Drifting Classroom as much a story of social order breaking down as it is a progression of disasters that a confused child might begin to imagine unfolding while panicked or under pressure. Parents hurt their children because they love them, until they don’t love them and start mowing them down with cars. A man who children are vaguely afraid of turns out to be a very evil man and strikes at children. Environments are confusing and bewildering, everything outside of the school is dangerous and unknown but what is inside the rooms. The scariest moments of The Drifting Classroom in its early volumes are equally the glimpses of a Lovecraftian, desolate wasteland as the crowded auditoriums, flocks of confused people who cannot settle down, a chaotic human rotation whose collective dissonant voice threatens to blot out the very ability to think. Bodies are painfully stiff, at once totally static and never settled into place. Sho does not know who he is, but he knows he is the hero, the world bends to his perspective while open ruins and packed rooms close in around him at every turn, the options being to look on and to scream. Perhaps Sho, a boy so clearly prone to paranoia, is well equipped for this nightmare world because he has been living under the impression that a nightmare might come this whole time.

The Drifting Classroom as much a story of social order breaking down as it is a progression of disasters that a confused child might begin to imagine unfolding while panicked or under pressure. Parents hurt their children because they love them, until they don’t love them and start mowing them down with cars. A man who children are vaguely afraid of turns out to be a very evil man and strikes at children. Environments are confusing and bewildering, everything outside of the school is dangerous and unknown but what is inside the rooms. The scariest moments of The Drifting Classroom in its early volumes are equally the glimpses of a Lovecraftian, desolate wasteland as the crowded auditoriums, flocks of confused people who cannot settle down, a chaotic human rotation whose collective dissonant voice threatens to blot out the very ability to think. Bodies are painfully stiff, at once totally static and never settled into place. Sho does not know who he is, but he knows he is the hero, the world bends to his perspective while open ruins and packed rooms close in around him at every turn, the options being to look on and to scream. Perhaps Sho, a boy so clearly prone to paranoia, is well equipped for this nightmare world because he has been living under the impression that a nightmare might come this whole time.

Umezz’s drawings of children screaming, eyes flashing as they comprehend some horrible reality before them are rightfully iconic, but what is even more impressive is how the presentation of his comics convey and complement the emotional landscape behind those pained expressions. Where some artists would use slash pages and “cinematic” sequences for fast-moving action, Umezz almost seems to freeze time in his larger compositions. Splash pages are weighed down by oppressive detail, events that might last only an instant spread out over multiple frames - so far as to even use up multiple splashes - slowing down each moment to the speed at which the child onlooker comprehends the horrific event. Consider the amazing sequence in the first chapter as Sho’s friend sees the crater where the school once was, taking entire pages to shift our focus from the boy’s look of shock to the sheer scale of the rupture. It is a bit cinematic, a “panning out” of sorts, but it also gives the reader a moment to share that moment of shock, that cognitive pause where the impossible and dreadful takes a step to even register as real. Or in the next chapter, when we see the event from the children’s perspective, a whole page is devoted to the split second before the traumatic tremor begins in full force, a classroom of children looks straight toward the viewer in slack jawed, wide-eyed terror anticipating the next page’s rattling turmoil as all is disturbed by the quake. By contrast, “action” happens quickly over sequences of smaller, talky panels, the busyness of the frantic story made even more absurd by how bizarre Umezz’s characters look when they are running as they most often are. Everything is lightning fast, at a fight or flight pace...except those eloquent, patient renderings of horrific realizations. The pace of the comic resembles the emotional time of real fear - there are moments that seem to last forever and sights that linger in our minds, and under the pressure of those instances the energy spent in all that time surrounding whips past in a blur.

Umezu’s commitment to a childish point of view is uncompromising. This is what gives the work its ferocity, and it’s also what spoke to me when a was a young man who did not understand why the world confused me greatly. Social interactions laced with catastrophe and doom, because the kids are doomed, but many of us feel doomed. Sadly it also contributes to the chauvinistic sexism that plagues much of the series. Umezu’s caricature of militant feminism, in which a bratty clique ringleader uses the fact that “girls grow up faster than boys” to briefly dominate the school, is frankly disturbing, but it is also worth acknowledging Sho’s friend Saki is regularly diminished, mocked and sidelined. This is not a failure per se, but these moments of barely questioned prejudice demonstrate a shortcoming of the style of totally absorbing empathy that rules Umezz’s world - The Drifting Classroom is so thoroughly invested in the perspective of a boy’s anxious worldview that another point of view can never really be offered.[4]

Umezu’s commitment to a childish point of view is uncompromising. This is what gives the work its ferocity, and it’s also what spoke to me when a was a young man who did not understand why the world confused me greatly. Social interactions laced with catastrophe and doom, because the kids are doomed, but many of us feel doomed. Sadly it also contributes to the chauvinistic sexism that plagues much of the series. Umezu’s caricature of militant feminism, in which a bratty clique ringleader uses the fact that “girls grow up faster than boys” to briefly dominate the school, is frankly disturbing, but it is also worth acknowledging Sho’s friend Saki is regularly diminished, mocked and sidelined. This is not a failure per se, but these moments of barely questioned prejudice demonstrate a shortcoming of the style of totally absorbing empathy that rules Umezz’s world - The Drifting Classroom is so thoroughly invested in the perspective of a boy’s anxious worldview that another point of view can never really be offered.[4]

While Umezz’s later seinen horror takes his vivid nightmare logic into even more disturbing graphic territory, The Drifting Classroom is the one where he finds something special, a culmination of scary stories for children that imagine scenarios where that irrational thing you worry about happening but never does is real and surrounds you. Eventually The Drifting Classroom builds to a kind of liberation, Sho becoming a mythically perfect leader guiding his child peers out of total despair, from literal class struggle to unified solidarity. Yet the greatest strength of The Drifting Classroom, what makes it a masterpiece of comics that will surely endure, are those moments where its children are hopeless, constrained, stiff, bound to the wooden stake as the flames roar, finally granted the freedom to scream out loud.

[1] Of the old edition, that is.

[2] I’m pretty sure it was manga critic Jason Thompson’s anecdote but I can’t seem to find the quote in any of the several articles where I remember it appearing.

[3] Shout out to the back cover of my paperback copy of Beckett’s Three Novels for giving me this wonderful turn of phrase that I promise to overuse until the day I die.

[4] That said, some satisfying subversive readings to the contrary are out there - I really dig Jog’s revisionist interpretation of the Sho’s mother interlude from many years ago for the now-defunct Hooded Utilitarian.