Fist of the North Star proposes then resolves a Third World War in a single opening page.

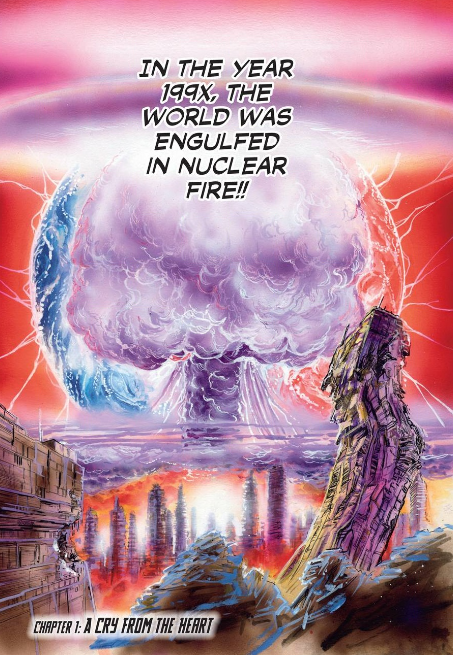

The crackling violet mushroom cloud of a thermonuclear detonation is deployed as a bulbous plume of exposition, a world-shattering cataclysm invoked to get the manga’s readers exactly where they need to be: a time and place in which civilization no longer exists. Serialized in Shūeisha’s Weekly Shōnen Jump magazine from 1983 to 1988, Yoshiyuki Okamura (writing under the heat-packin’ pen name Buronson) and Tetsuo Hara’s creation has endured as the foundation for a pop culture phenomenon that continues to this day, spawning everything from feature-length animated and live-action films to bespoke electronic books and arcades packed with licensed pachinko machines.

Newly reissued in English by VIZ Media as part of their hardcover Signature line, the series benefits from a translation—provided by Joe Yamazaki—that eschews the flat declaratives and incessant swearing pasted over ancient fanscans to arrive at a mode of written communication that firmly contextualizes Fist as a (bloody) Boys’ Own style adventure, laundering the post-apocalyptic wasteland seen in more adult fare like George Miller’s Mad Max films or Gō Nagai’s Violence Jack manga. The explicit sexual terror of those works is dialed down so as to be more suitable for Jump’s younger audience, though the constant bodily trauma remains. Armageddon’s survivors are, broadly, divided into gangs of muscular monsters and their cowed chattel - predators and their prey. The apocalypse then is used as a pretext to return mankind to a tumultuous era of feudalism, one in which water is limited and violence rules the day. Hara’s linework describes this brutality, and the brawn that drives it, in markedly distinct ways. Although ferociousness is standard, heroes and villains resolve conflict differently. The gangs that rule the ruins of the 20th century are massive and uniform; they are the human body as a thick, steroid-pricked nightmare to be used purely in the service of cruelty.

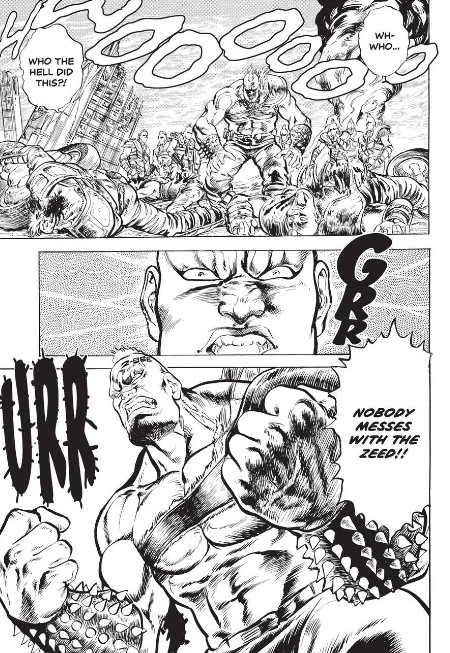

The anonymous, foot soldier-level villains seen in these first four volumes are culturally similar to the kabukimono hooligans of Japan’s warring states era, though—while the visual language employed in their rendering is likewise cultivated and doting—these vein-popped monstrosities are portrayed with a more modern, 1980s action movie aesthetic. They are Muscle Beach warlords, swinging their axes in a gutted, irradiated Japan. The basic characteristics of these brigands may change as the story progresses—a motorcycle horde in the second book; a pack of lupine savages that feast on human flesh in the third—but the premise remains the same: unnaturally powerful bodies completely untethered from any moral framework. The manga’s hero, Kenshiro, may be similarly pumped-up but his body is honed, his energies restrained rather than exploding. Ken, as the true heir to the Hokuto Shinken assassination style, has complete control of his physique. This martial artist is able to manifest techniques and forms, as required, like a Silver Age Superman born from fire and brimstone. Hara draws his hero as a handsome mix of Mel Gibson’s Road Warrior adorned with the thick eyebrows and striated physique of Bruce Lee; a matinee idol breezing through hell. The opening chapter in the first volume portrays Ken in similarly adoring terms: a magnificent stranger with quasi-religious undertones. John Hunt’s art touch-up and English lettering leave Hara’s artwork appearing pristine to the point of luminescence. The grayscale muddiness that can often mar black and white manga reproduction is completely avoided.

Ken’s motivations, at least at this point in the story, are deliberately thin. Stumbling upon a besieged township while suffering a state of delirium, Ken is greeted as just another future-shocked wanderer. He is thrown into a makeshift prison by the town’s frightened militia and left there until an elder can arrive to dispense judgment. Okamura writes Kenshiro as polite and disarmed, not at all worried about his current predicament. Ken fulfills an archetypal, easily understandable function—the unruffled outsider hiding incredible technique—but the abilities of this newcomer go beyond that, demanding an almost Biblical consideration. Not only can Ken heal Rin, the stricken child who attends to his cell, but when he is brought before the village’s doddering leader, we discover that Ken’s body is covered in scars. Hara dots his hero’s chest and stomach with pitted wounds that resemble Ursa Major, the North Star constellation. Not content to simply state the manga’s name within the text, Okamura and Hara make it a bloody stigmata on their hero’s body. Further stories treat the religions of the world as all-purpose grist for a tale heading towards a heavenly detonation. Shinto creation myth and Hindu heroism mix and intermingle, marking Ken as an all-conquering God of Death who brings karmic balance to this blighted world.

When Zeed bandits arrive to burn the homestead in vol. 1, though, Ken doesn’t immediately spring into action. This village imprisoned rather than helped him, after all. It’s only when he discovers that Rin’s life is in immediate danger that Ken hurtles after the child. This anti-heroic affectation betrays a character apparently attuned to a similar kind of moral frequency as a boisterous schoolyard. A more ruggedly civic stance might position the newly-minted Ken as some sort of do-gooder dweeb to his young readers; not an ideal framing for a loner steeped in fantastical martial arts. Bullying though, especially directed at what amounts to a sickly preschooler, is a predicament any pre-teen can understand, relate to, and perhaps even want to thwart. Endangered youngsters are a recurring motivation in Fist of the North Star then. Children are beaten and brutalized throughout, prompting Ken to quietly seethe, then act. Youngsters—very much the piece’s intended audience—are used as a kind of currency in this manga; harm visited upon them will be repaid tenfold.

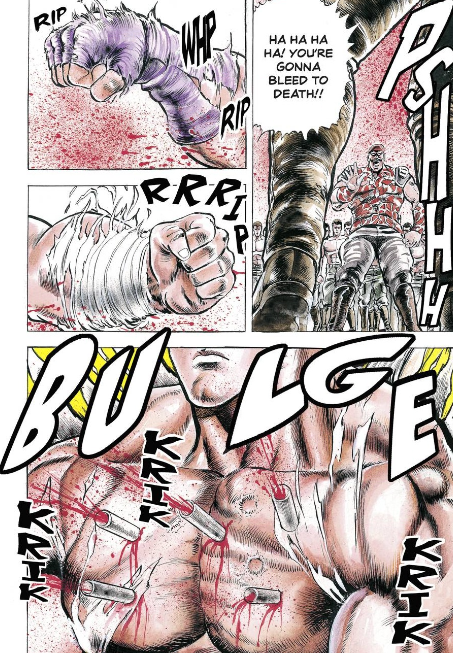

Even when not specifically dealing with children, threat is assessed in terms of human dimension. Hara accentuates the helplessness of the civilian characters in Fist of the North Star’s confrontations by drafting his savages in absurd terms, as if viewed from the perspective of somebody themselves still growing. Throughout VIZ’s four available volumes, the male form is positioned as grotesque and physically overwhelming. Mohawked malcontents have fingers massive enough to ensnare entire skulls; pachyderm sized bruisers seem to grow (and grow and grow) between panels. Smug commandos radiate thick wafts of cosmic intent, smoke rolling off them as they themselves are a blazing fire. Hara uses this deliberately surreal portraiture to illustrate not just the level of danger these figures represent, but also to offer readers a measuring stick by which we can gauge Ken’s seemingly bottomless strength. Ken’s answer to these outrages is pure, hormonal, wish-fulfillment: martial arts techniques so precise that it frequently doesn’t matter that he hasn’t obviously—immediately—hurt his opponents, they are already dead. Ken’s attacks are not designed to do anything as gauche as bruise an eye or break an arm; instead, he deploys directed finger jabs to obliterate chakra lines in his enemies. The brutes of the wasteland are defeated on a metaphysical level.

Fist of the North Star, at least initially, positions the swollen musculature of its villains as cloddish and unthinking. It’s probably no coincidence that Ken’s attacks cause their bodies to bulge and warp in obscene ways before detonating. Their flesh and bone hasn’t been drilled in such a way that they are able to channel or control these haywire life energies. While later volumes go to great lengths to depict a strenuous back-and-forth between Ken and his foes, particularly when Ken’s estranged family are stirred into the mix (Jagi, a failed heir to the Hokuto Shinken legacy whose head is held together by screws and metal, is introduced towards the end of the third volume; the despondent Toki and the indomitable Raoh debut in the fourth), the stories collected in these earlier hardbacks have an identity all of their own precisely because they lack a standard sense of tension. Hara’s panel progression often deliberately defies any obvious temporal concern. A crossbow bolt can be snapped out of the air in one panel; then, by the time we see the next, Ken has already—invisibly—deposited the arrow into his assailant’s eye. It’s not that we’re missing key information so much that Okamura and Hara are explicitly telling us that Ken’s actions are simply too quick to be captured.

Ken's adventures will take him deeper and deeper into the wasteland, battling systems and bloodlines with roots extending back into the distant past. This incessant genealogical conflict will reveal monsters who straddle the divide between the mutated musculature of petty post-apocalyptic fiefdoms and the martial arts expertise that Kenshiro wields. These conquerors, though, defined primarily by their egotistical self-sufficiency, cannot heal the Earth. They can only exploit it, repeating the patterns and mistakes that marched the world into this period of nuclear darkness. Fist of the North Star's hero then holds himself to a higher, much more chivalrous ideal than any of his body-warping brothers: protecting those with the capabilities to return mankind to some semblance of civility. Ken fights for the children.