Massimo Mattioli, Italian comic innovator and irreverent mixer of genres, styles, and cultural levels, passed away last month at age 75. He was a central figure in the movement that conjugated the pop language of comics with the highbrow world of contemporary arts in the late 1970s and 1980s. Since 1977, he was also a key member of the Cannibale group, a cluster of artists (including Andrea Pazienza and Stefano Tamburini, among others) tied to important magazines such as the eponymous Cannibale and Frigidaire. Known to English-speaking audiences mainly for his Squeak the Mouse saga, Mattioli’s artistic output is in fact tremendously vast and diverse, ranging from deceptively innocent children’s stories, published in Italian Catholic magazines such as Il Giornalino, to the sex-guts-and rockets yarns of his Frigidaire contributions. Mattioli’s career is also singular, in the context of Italian comics, because he was one of the very few Italian comic artists to make a name for himself abroad before actually establishing his career in his own country.

In 1965, at age 22, Mattioli debuted as a comics artist and soon landed in the pages of Il Vittorioso, a venerable Italian Catholic comics magazine. For its pages Mattioli drew strips like Vermetto Sigh and Gatto Califfo, aimed at very young readers. In 1969 he moved to London, where he published in the magazine Mayfair, and then to France. Here, he contributed work to the popular children’s comics magazine Pif Gadget with the surreal comic M le Magicien. Influenced by late 1960s psychedelic aesthetics and by both George Herriman’s Krazy Kat and Pat Sullivan’s Felix the Cat, the stories of M le Magicien feature a wacky magician; his sidekick, a chameleon who can devour practically anything including balloons and page borders; a couple of goofy Martians; and a cast of talking daisies, mushrooms, and flies.

In 1973, back in Italy Mattioli introduced his character Pinky, a pink rabbit photojournalist in the pages of Il Giornalino, a prestigious comic book magazine for young readers published by Edizioni San Paolo, a Catholic publisher tied to the Vatican. From this point on, for the next 40 years, Mattioli continued producing Pinky stories even while working on some of his most adult-oriented and outrageous creations like Squeak the Mouse and Joe Galaxy.

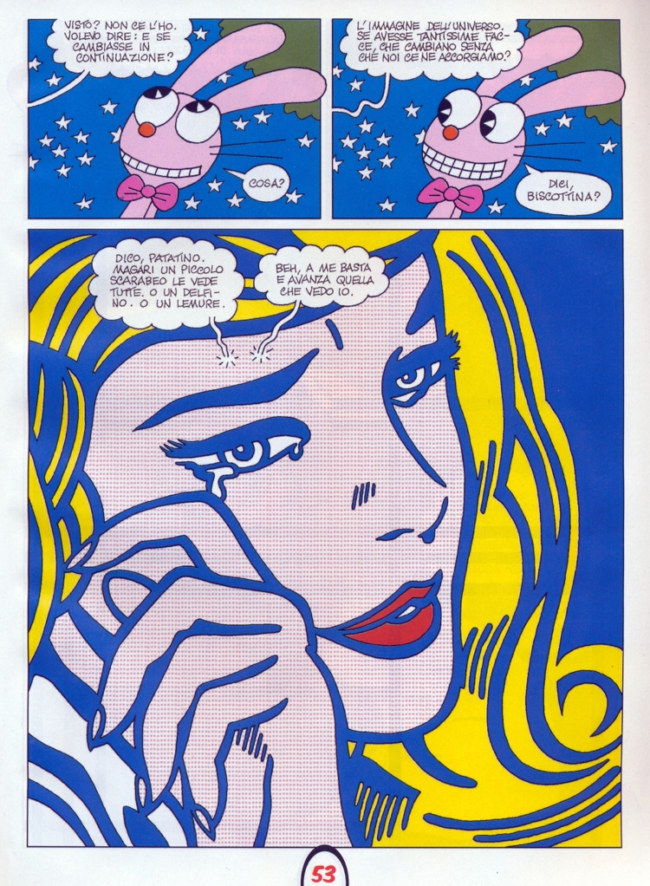

Already from this early stage of his career, Mattioli started to develop the metanarrative poetics that would mark the rest of his work. Pinky immediately displayed a voracious intertextual component, a penchant for breaking the fourth wall and for playing with and subverting the components of the medium. Drawn with a ligne claire style, Pinky is set in a world that could very well be a modernized and simplified version of Carl Barks’ Duckburg. The inside references to the world of comics and pop culture abound. In early stories there are cameos by Little Orphan Annie, Mickey Mouse, Superman, and even the four Droogs from Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange (or rather Stanley Kubrick’s version of them). As the series continues, through the mid-1970s, there are references to Jack Arnold’s The Creature from the Black Lagoon, Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, Moebius’s Arzach, Pop-art superstar Roy Lichtenstein, Pablo Picasso, and even Mattioli’s own Squeak the Mouse (minus the slashing), to name just a few.

A close reading of Pinky shows clearly that its postulated audience is not the young readers that it seems to address. Instead, within its one- to four-page stories there are meditations about space and time, the relation between narrative and reality, a subtle and sly Zen-like poetry, and a genuine sense of cruelty and violence that was certainly designed to go over its young readers’ heads. If the great revolution in Italian comics ushered in by the advent of the Cannibale and Valvoline groups in the late 1970s and early 1980s was eminently and omnivorously intertextual, Pinky is certainly its legitimate forerunner.

In 1977 Mattioli met Stefano Tamburini, known to English-speaking audience for his ultra-violent saga RanXerox, and together they founded the magazine Cannibale, a game-changing publication in the context of Italian comics. To understand the role and the importance of the magazine it is necessary to provide a little context on the state of the medium in Italy at the end of the 1970s. Up until 1977 the world of Italian comics was strictly divided in two: first, the realm of auteur comics with artists like Hugo Pratt, Dino Battaglia, and Guido Crepax, all of them connected to the groundbreaking magazine Linus (est. 1965), responsible for opening the readership of comics to an audience of older, college-educated readers. Auteur comics, like Pratt’s Corto Maltese or Crepax’s Valentina where respected by literary critics and analyzed by literary superstars like Umberto Eco or Italo Calvino; their cultural referents, with whom these authors interacted with a sense of reverence, belonged to an arsenal of nineteenth century and early-twentieth century icons: Robert Louis Stevenson and Joseph Conrad for Pratt, Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung for Crepax. On the other end stood the popular comics: humor publications for the very young, western and adventure comics, the adults-only erotic/porno publications and the pulp crime titles like Diabolik and Kriminal. The new wave of Cannibale (whose group soon expanded to include Filippo Scòzzari, Andrea Pazienza, and Gaetano Liberatore) subverted this divide by producing comics that were coming from the lowbrow side, but that dared to confront the high arts—especially the post-pop and postmodern figurative artists—on equal grounds. They also introduced a breath of fresh air in Italian comics by importing a wide knowledge of European and, especially, underground American comic artists.

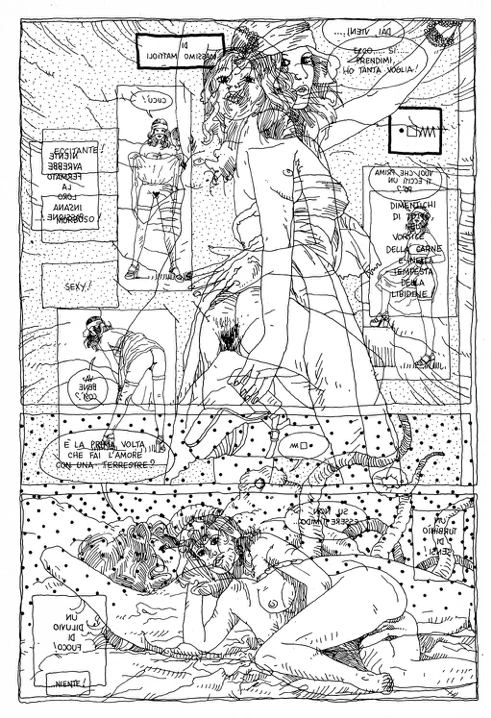

In the pages of Cannibale, free from the artistic limitations of magazines like Pif or Il Giornalino, Mattioli was finally able to experiment freely with the medium. Besides a slew of characters like the wonderful Gatto Gattivo, a pot-smoking delinquent cat besieged by a not-very-bright police dog, Mattioli contributed some real masterworks of infraction to the norms of the genre. In Champagne and Novocaine, Mattioli used the Burroughsian cut-up method, re-composing a pre-existing story whose panel themselves were traced and modified from one of Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon Sunday pages. This technique of détournement, popularized by the Situationist Internationalist artists in the 1960s, which consisted of appropriating and modifying a pre-existing text, was a favorite of the Cannibale group; both Mattioli and Tamburini (who later released a series called Snake Agent obtained by modifying original Agent X-9 strips with a photocopy machine) employed it frequently in their works. In MMO•, a two-page story seemingly narrating a sexual encounter between an alien and an earth woman, Mattioli went even further and used the practice of détournement on his own story by instructing the printer to superimpose the first page on the second, leaving the first one blank. As a young reader I was always captivated by the effect of confusion and mystery caused by what I thought was a genuine printing mistake. Only recently, some 30 years later, reading Mattioli’s notes to Bazooly Gazooly, a collection of his works published this summer in Italy by Comicon, I found out that this was indeed an intentional strategy!

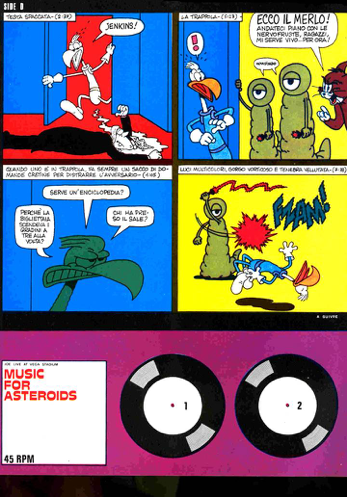

Yet, from an experimental point of view, Mattioli gave his best on the pages of Frigidaire, the magazine that Cannibale morphed into in the 1980s. Here he launched one of his most iconic heroes, Joe Galaxy, an anthropomorphic eagle/hard-boiled space adventurer. Joe Galaxy’s first story, Joe Galaxy e le Perfide Lucertole di Callisto IV, extending through the first 9 issues of the magazine, is among Mattioli's most formally adventurous where one can really sense his own enjoyment as he unhinges, episode by episode, every formal rule of comic book grammar while still telling a perfectly legible and enjoyable story. Each episode of the story adopts a different panel arrangement within the page. One episode has three strips per page and a color palette meant to allude to Piet Mondrian (a reference reinforced by the use of black gutters between panels), making the page both a narrative sequence and a synchronic painterly whole. Another is built with a classic regular cage of three-panel/four strips presenting a classic action episode where the whole attention is directed toward the steady fast rhythm of the narrative. Yet another one is arranged so that the panels represent each a track of a double LP record, Music for Asteroids; each panel/track comes with a caption specifying its duration and each of the four pages of the episode corresponds to a side of the double LP. Even the drawing style changes often from panel to panel within the same page. In Joe Galaxy e le Perfide Lucertole di Callisto IV, Mattioli adopts alternatively the thin ligne claire of Pinky, a painterly brush heavy line, found materials, collages, sex toy ads from porn magazines, and coloring schemes that include saturated monochromes, the palette of collage artists like Richard Hamilton and Eduardo Paolozzi, and Mondrian’s primary colors.

The pages of Frigidaire also hosted the debut of the character that non-Italian readers most immediately associate with Mattioli’s name: Squeak the Mouse. The whole saga actually sprung from a single black and white stand-alone story. Mattioli successively added a number of sequels that were collected into two books in the 1980s (a complete collection including a third never-before-published album was recently put out by Coconino in Italy). The original story is a classic cat against mouse yarn, Tom and Jerry-style, with the added twist that the violence implicit in its model in the end has actual real consequences. In the conclusion of the story, after a series of slapstick tricks that the cat and the mouse play on each other, and that leave them both unharmed, the cat actually kills the mouse by eating him after splattering his body against a wall.

The following episodes develop with an accumulative logic: the mouse comes back as a zombie to seek vengeance, then as an army of zombies, and is even resuscitated by way of alien technology. In a way, paradoxically, the logic of the story realigns Mattioli’s comic with its original cartoon models: cat and mouse are actually immune to harm. The saga quotes freely from the slasher and zombie movies of the late 1970s and 1980s with loads of sex and gore and plenty of cute anthropomorphic pussycats. Much has been said about Squeak the Mouse actually serving as model for Matt Groening’s "The Itchy and Scratchy Show" in The Simpsons, but the diatribe is in the end meaningless (one could point out that everything was already there in cartoons like Tom and Jerry, Herman and Katnip, the very violent 1973 comic book oddity Kit’n’Kaboodle by Brian McCoonachie and Warren Satler, or even Rand Holmes’ 1977 Nip and Tuck, for that matter). Mattioli himself in a recent interview for an Italian newspaper had this to say about the subject: “I don’t give a damn. With the new collected edition out, the readers will decide. These things are not good for your health, you risk getting stuck in a hallucinogenic vicious circle. What should I do, hate him? No […] I prefer being poorer but free.”

Other highlights of Mattioli’s long collaboration with Frigidaire include gems like Il caso Ian Curtis (1982), a black and white Chandler-esque noir with a private eye investigating the death of Joy Division’s singer (and featuring the comic artist Richard Corben, looking much like his character Den, as a producer of bootleg albums); Guerra, an excursion in the realm of painting, narrating the last battle between laser-eyed angels and a band of devils in a barren wasteland; a series of one-pagers inspired by EC comics and '50s horrors; and Frisk the Frog, where Mattioli again delves into the comic book/record genre, complete with album cover.

The comic/song was actually put into music and published in 1984 as a dance track by Maurizio Marsico of Monofonic Orchestra.

The collaboration with Marsico continued with one of Mattioli’s most openly postmodern works, Ingordo. Produced with an array of diverse graphic devices including marker drawings, pen and ink, photos, collages and abstract color compositions, Ingordo (Glutton) tells the story of an omnivorous narrator and his journey through a path of assimilation of incongruous data that are “postmodernly” received as de-hierarchized cultural experiences. The narrator indifferently absorbs religions, philosophies, learns how to pilot planes, how to play football, contracts various diseases with the same curiosity with which he consumes books (from literary masterpieces to botanical manuals), and then finally learns how to eat—vegetables, meat from all kinds of animals, human flesh. In the last page we are finally shown the real face of the narrative voice, an adipose blonde woman in shorts drawn in Roy Lichtenstein’s style holding a Warhol-esque can of Budweiser. But the stunningly diverse body of work Mattioli produced for Frigidaire is hard to exhaust in the space of these brief notes.

At the same time, while also continuing his work on Pinky in the pages of Pif and Il Giornalino, Mattioli worked in the field of graphics and advertisement, publishing for magazines such as Vanity and Vogue. In 1989 he produced the animations for Robert Palmer’s video Change His Ways. With the end of his collaboration with Frigidaire, in the late 1980s, Mattioli’s work appeared in prestigious Italian comics magazines like Comic Art (where he published further Joe Galaxy adventures) Alter, and Corto Maltese. In Spain he was published in El Vibora and in France in L’Écho des Savanes and in Lapin, the magazine of the group L’Association. But this is only a partial list. Recently, collections of his works have been reprinted in Italy by Coconino and Panini and also in France, Spain, Brazil and Russia. L’Association has published volumes collecting his early French works. Pinky, unfortunately, still awaits a complete collected retrospective.

A volcanic and proteiform artist who pushed the limits of the comic book medium, Mattioli left us a body of work that is encyclopedic in nature and volume. He built worlds where Niels Bohr and pink rabbits, Piet Mondrian, zombies from a Lucio Fulci movie, New York no-wave bands, talking flies, and sex-crazed space lizards all walk the same streets and cross paths incessantly. On a personal note, while putting this article together and going through my old issues of Cannibale and Frigidaire I was reminded how, as a very young reader, Mattioli’s stories seemed to draw a map of a territory that I was very desperately trying to find for myself. And through the abstraction of his storytelling he let the coordinates show very clearly: it all started at the corner of the zombie mouse with the chainsaw and the pink rabbit with the camera.

Massimo Mattioli leaves an enormous void in the context of Italian comics and in the world of comics in general. Hopefully, with the recent reprints of part of his work in Europe, publishers in the U.S. will follow suit so that American readers will have the possibility to appreciate one of the true greats of European comics.

* * *

Simone Castaldi is Associate Professor of Italian at Hofstra University in New York, where he teaches comics, cinema, modern and contemporary literature, the Italian language, and history. He is the author of the first in-depth English-language study of Italian comics, Drawn and Dangerous: Italian Comics of the 1970s and 1980s (University Press of Mississippi), and of numerous articles on European comics and Italian cinema. His most recently published work is a chapter on the history of Spanish and Italian comics in The Routledge Companion to Comics. For Fantagraphics he has contributed critical essays for The Complete Crepax series of books and translations to the first English-language edition of Andrea Pazienza's Zanardi and Romano Scarpa’s The Return of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. He is currently co-translating Hugo Pratt's complete Corto Maltese, an Eisner and Harvey award-nominated 12-volume series for The Library of American Comics (IDW).