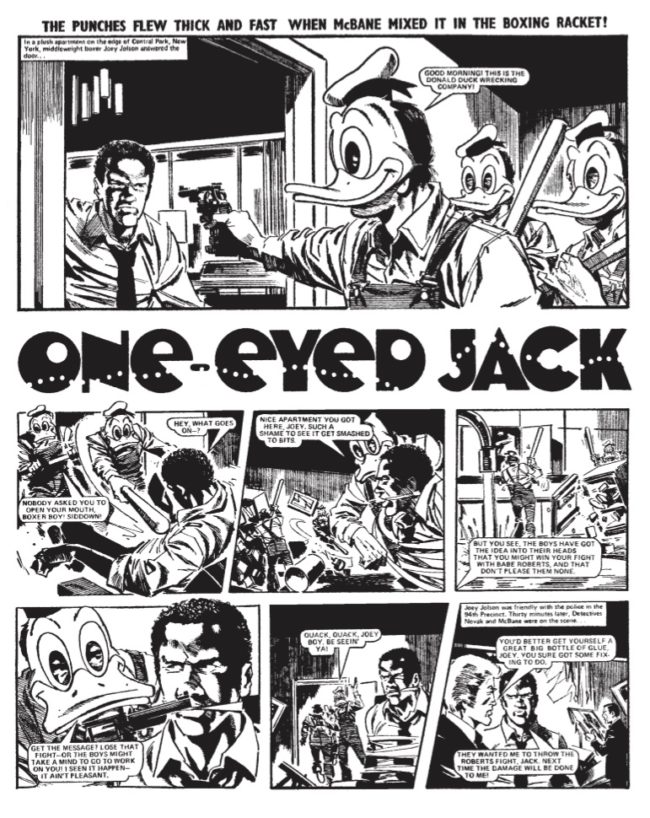

Judge Dredd's antecedent in weekly British comics was a one-eyed NYPD detective named Jackson Delaware McBane, who thought nothing of strangling a man with a snake and once squeezed himself into a luggage locker at Grand Central just so he could spring out and shoot the man who opened it. By the time Valiant serialized One-Eyed Jack by John Wagner and John Cooper in 1975 the comic was on its last legs, which Wagner took as latitude to serve up hyperbolic mayhem for 12-year-old British boys whose view of US policing was based on Kojak, just as Wagner's own view was being shaped by Clint Eastwood. The writer remembered this approach later when co-creating Judge Dredd for 2000AD; but Valiant itself flamed out and vanished into the cosmos. Weekly British adventure and mystery comics of the era—boys' titles like Valiant and Battle and Jet, plus a separate ecosystem of girls' comics often bearing the fingerprints of writer Pat Mills—were transient by nature, acute doses of hectic cartooning on newsprint that sometimes fell apart while you were reading, potentially lost to the ages within days when the next issue rolled in.

Judge Dredd's antecedent in weekly British comics was a one-eyed NYPD detective named Jackson Delaware McBane, who thought nothing of strangling a man with a snake and once squeezed himself into a luggage locker at Grand Central just so he could spring out and shoot the man who opened it. By the time Valiant serialized One-Eyed Jack by John Wagner and John Cooper in 1975 the comic was on its last legs, which Wagner took as latitude to serve up hyperbolic mayhem for 12-year-old British boys whose view of US policing was based on Kojak, just as Wagner's own view was being shaped by Clint Eastwood. The writer remembered this approach later when co-creating Judge Dredd for 2000AD; but Valiant itself flamed out and vanished into the cosmos. Weekly British adventure and mystery comics of the era—boys' titles like Valiant and Battle and Jet, plus a separate ecosystem of girls' comics often bearing the fingerprints of writer Pat Mills—were transient by nature, acute doses of hectic cartooning on newsprint that sometimes fell apart while you were reading, potentially lost to the ages within days when the next issue rolled in.

But lost no longer. Those titles and others, output of the long-gone IPC Youth Group and having languished for decades on the books of disinterested successor publishers, are back in business. Their rescuer is Rebellion, the Oxford-based group that started out as a games developer before moving into publishing, and which bought 2000AD from its then-publisher Fleetway in 2000—a transaction that the memoirs of creators such as Mills frame as more of a liberation.

Rebellion chiefs Jason and Chris Kingsley were motivated by enthusiasm for 2000AD, although the recent creation of Rebellion Productions to facilitate a Judge Dredd TV show and a Rogue Trooper movie proves that there's no ignoring other avenues to revenue in the era of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. But back in 2016 Rebellion goosed its comics interests considerably by purchasing the majority of IPC's post-1970 comics archive, and followed up in 2018 by buying most of the pre-1970 material as well. That means that the bulk of UK comics heritage not already under the Beano-shaped umbrella of DC Thomson now rests in just the one place. Rebellion said at the time that it would be "bringing books into the conversation," an acknowledgment that making any money via periodicals alongside 2000AD was a hefty challenge, and the archive has duly started to appear in paperback reprint albums, under a Treasury of British Comics imprint.

Swimming in an ocean of British comics mostly unseen since the 1970s and 1980s can give you a nostalgia trip or the bends. The sentimental aspect, inevitable if you happen to have been reading some of this stuff the first time round, is less interesting now than the stylistic approaches of creators faced with a relentless weekly schedule of short four or five-page episodes, mostly in black and white. The baseline pace of the art is supersonic; the style is rough hewn and aggressive, plainly the work of human hands; and the plots look set to roll on for as long as the comic may last, all digression squeezed out by the density of the storytelling while definitive endings recede like the horizon. And notwithstanding the laudable resurrection of historical cartooning, it's a clash of original form and newfound function. Although Rebellion does not reveal sales figures, and the numbers for the Treasury imprint can only be guessed at, routes into 150-page slabs of 150-MPH black-and-white comics created for teenagers might not materialize for casual readers without some decent guidance and husbandry. Closing the loop between Judge Dredd and Dirty Harry via One-Eyed Jack is one thing; but what readership is out there keen to beat a path back to Dirty Harry? And how old are they?

The Treasury books have showcased some bolts of creative British lightning, worth savoring as they flash past. Unsurprisingly wars, ie. World War II or its proxies, loom large. In Von Hoffman's Invasion, a 1971 strip by Tom Tully and Eric Bradbury rescued from Jet comic, a very mad Nazi scientist enlarges animals and insects into huge rampaging monsters and brews up a plan to kidnap England's greatest soccer player. His eventual defeat could hardly be unconnected to the small matter of England's real-world loss of the World Cup to West Germany the year before; never claim that the creators of comics are out of touch with the concerns of their readers. The Leopard from Lime Street by Tully, Mike Western and Bradbury, is relatively sedate, gorgeously drawn, class-conscious, and not so much inspired by Lee and Ditko Spider-Man as a loving palimpsest over the original, right down to the 13-year-old boy who gets scratched by a radioactive leopard.

The Treasury books have showcased some bolts of creative British lightning, worth savoring as they flash past. Unsurprisingly wars, ie. World War II or its proxies, loom large. In Von Hoffman's Invasion, a 1971 strip by Tom Tully and Eric Bradbury rescued from Jet comic, a very mad Nazi scientist enlarges animals and insects into huge rampaging monsters and brews up a plan to kidnap England's greatest soccer player. His eventual defeat could hardly be unconnected to the small matter of England's real-world loss of the World Cup to West Germany the year before; never claim that the creators of comics are out of touch with the concerns of their readers. The Leopard from Lime Street by Tully, Mike Western and Bradbury, is relatively sedate, gorgeously drawn, class-conscious, and not so much inspired by Lee and Ditko Spider-Man as a loving palimpsest over the original, right down to the 13-year-old boy who gets scratched by a radioactive leopard.

Bradbury was a prolific British master, but the Treasury reprints lay out the reliance on foreign artists working through agencies upon which the IPC system was built. It's a culture clash that can produce alchemy, as when Bradbury began Black Max in Thunder and then handed it over to the Spaniard Alfonso Font, whose looming shadows and spotted blacks are perfect for a story in which a vampiric German World War I fighter ace flies into battle alongside giant vampire bats. El Mestizo comes from the pages of Battle, one of several strips that Carlos Ezquerra contributed during the period that 2000AD was taking off, and follows a former slave turned mercenary in the American Civil War. It's written by Alan Hebdon, but the Western world springs fully formed from Ezquerra's idiosyncratic European pen in a way that might have matched Jean Giraud and Blueberry if it had continued longer.

And whatever else the Treasury imprint achieves, its publication of work from the forgotten hinterland of British girls' comics, mostly created by men but with some significant contributions from women, could be a cultural rescue mission. Pat Mills, who wrote or edited several of them, has said that girls' comics relied on character under duress rather than strength under fire, which made for better comics than the ballistic bedlam of the boys' sector. Read in the current moment it also makes for stories about crises of principle rather than crises of identity, distinctly against the prevailing grain. Alan Davidson and Phil Gascoine's Fran of the Floods from Jinty proves the point, invoking something not yet called climate change to create a flooded Britain in which two girls are forced to look out for each other as they struggle to reach Scotland. Mills called Davidson "the Alan Moore of girls' comics," and the Treasury reprint could let a new readership see what he meant.

And whatever else the Treasury imprint achieves, its publication of work from the forgotten hinterland of British girls' comics, mostly created by men but with some significant contributions from women, could be a cultural rescue mission. Pat Mills, who wrote or edited several of them, has said that girls' comics relied on character under duress rather than strength under fire, which made for better comics than the ballistic bedlam of the boys' sector. Read in the current moment it also makes for stories about crises of principle rather than crises of identity, distinctly against the prevailing grain. Alan Davidson and Phil Gascoine's Fran of the Floods from Jinty proves the point, invoking something not yet called climate change to create a flooded Britain in which two girls are forced to look out for each other as they struggle to reach Scotland. Mills called Davidson "the Alan Moore of girls' comics," and the Treasury reprint could let a new readership see what he meant.

Readership, and royalties: archival projects require both. Rebellion hasn't commented explicitly on creator compensation either, so you have to take it on faith that the estate of the late Phil Gascoine has benefited appropriately. But you also have to note that some strips have already been reprinted with their creators officially unnamed and unknown, and if a project of this scale labels them that way, then presumably the names are gone for good.

The appeal of these reprints for current readers of 2000AD, or indeed for precious readers unconnected with 2000AD at all, is tricky to assess. In 2017, 2000AD editor Matt Smith reckoned that the older characters were unlikely to appear in his comic; but the lure of a Rebellion Connected Universe has proved strong. Two Scream & Misty Halloween Specials in 2017 and 2018 printed new material created around a handful of the old characters by 2000AD writers and artists; and between them came the start of an annual series called The Vigilant, essentially forming a superhero team out of some Treasury characters and a couple of non-headline Rebellion properties. That strip was drawn by Simon Coleby, a modern heir to the war comics artists of old, whose smoky and mildly tortured pencils made the strip feel entirely like one of 2000AD's space-war stories for adults, into which characters shaped around the thoughts of teenagers had been bizarrely beamed. And in December 2018 the Black Max turned up in person in the ongoing 2000AD fantasy horror strip Fiends of the Western Front, splendidly rendered by Ian Edginton and Tiernen Trevallion and an entirely obvious place for the vampiric flying ace to surface—if you accept that the nostalgia he's expected to bring with him might be a boon, or might be a drag, and might not actually exist at all.

Nostalgia can only get you so far. In this I'm with Umberto Eco, who thought that stories fixated on the past mark a society with no sense of a future; and with Marc Singer, whose book Breaking the Frames discusses how pastiche and nostalgia are the end results of a huge surplus of cultural production, as part of Singer's drive-by truth-telling about pop-culture scholarship. Maybe there's just too much stuff, and finding more old stuff to mine for more new stuff does not help to slow down the carousel. This cultural craving turns into a cashflow challenge if you idly wonder what Rebellion would or could do to tend a new audience of 12-year-olds through the Treasury material, were it so inclined. 2000AD's readership is famously mature—"the comic has grown up with its readers" is still said from time to time as if the implications were not bleak on several levels—and a recent shot at an all-ages version of the comic was bafflingly presented as a one-off event approaching twice the usual cover price. One strip in The Vigilant is titled "Kids Rule," the most knowing of all possible nods backwards, towards the 1976 story "Kids Rule OK" in Action whose legendarily excessive violence was a factor in the creation of 2000AD in the first place. Rebellion has put its money where its mouth is by hauling several tons of British comics history up from an oubliette, but at some point it might need to turn its gaze 180-degrees and face the future with its prize.

Nostalgia can only get you so far. In this I'm with Umberto Eco, who thought that stories fixated on the past mark a society with no sense of a future; and with Marc Singer, whose book Breaking the Frames discusses how pastiche and nostalgia are the end results of a huge surplus of cultural production, as part of Singer's drive-by truth-telling about pop-culture scholarship. Maybe there's just too much stuff, and finding more old stuff to mine for more new stuff does not help to slow down the carousel. This cultural craving turns into a cashflow challenge if you idly wonder what Rebellion would or could do to tend a new audience of 12-year-olds through the Treasury material, were it so inclined. 2000AD's readership is famously mature—"the comic has grown up with its readers" is still said from time to time as if the implications were not bleak on several levels—and a recent shot at an all-ages version of the comic was bafflingly presented as a one-off event approaching twice the usual cover price. One strip in The Vigilant is titled "Kids Rule," the most knowing of all possible nods backwards, towards the 1976 story "Kids Rule OK" in Action whose legendarily excessive violence was a factor in the creation of 2000AD in the first place. Rebellion has put its money where its mouth is by hauling several tons of British comics history up from an oubliette, but at some point it might need to turn its gaze 180-degrees and face the future with its prize.