This month Philadelphia-based cartoonist Box Brown returns with a new, timely book of graphic non-fiction, Cannabis: The Illegalization of Weed in America. Over the last few years, readers have followed Brown’s evolution from a self-published creator and the founder of Retrofit Comics to the author of best-selling pop-culture titles about Andre the Giant, Tetris and Andy Kaufman.

This month Philadelphia-based cartoonist Box Brown returns with a new, timely book of graphic non-fiction, Cannabis: The Illegalization of Weed in America. Over the last few years, readers have followed Brown’s evolution from a self-published creator and the founder of Retrofit Comics to the author of best-selling pop-culture titles about Andre the Giant, Tetris and Andy Kaufman.

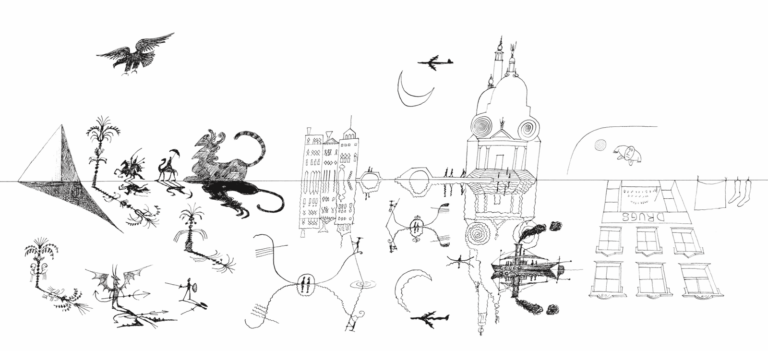

Cannabis might be Brown’s most epic work to date, taking readers on a detailed journey through the history of marijuana and America’s legislation against it. Much of the book focuses on Harry J. Anslinger, who led the movement to criminalize marijuana as the first commissioner of the U.S. Federal Bureau of Narcotics from 1930-62.

When he’s not making comics, Brown stays busy as the father of a 2-year-old. (His business partner, Big Planet Comics’ Jared Smith, has taken the lead at Retrofit.) A few days before heading out on his book tour, Brown was happy to chat about Cannabis, his relationship with obsession and his wide appeal.

Whitney Matheson: You’re in Philly, which seems to have a growing community of cartoonists.

Box Brown: It’s kind of like my adopted home. Over the last few years, a bunch of cartoonists have moved here from New York because the cost of living is so much cheaper. Philly has maintained itself as a working-class place and kept prices down in a way that other East Coast cities haven’t.

Do you work from home?

Yeah. I’ve been contemplating getting a studio, but unless you can find a super-small space, you have to get studiomates, which can be difficult. They opened a medical cannabis patient lounge in my neighborhood, and I became friends with the owners. I was thinking of renting out some space in there. (Laughs)

That would be appropriate! So your new book, Cannabis, continues a successful run of books with First Second. Was Andre the Giant your first nonfiction work?

That would be appropriate! So your new book, Cannabis, continues a successful run of books with First Second. Was Andre the Giant your first nonfiction work?

Before Andre the Giant, I was working on a series of comics called Everything Dies, which ended up being, like, 450 pages. More than half of it was nonfiction, and I self-published that. Then Andre was the first big nonfiction work that I did that wasn’t self-published.

Was it after Andre’s success that you realized, “Oh, I might be onto something here?”

My interest in nonfiction, I think, stems from an interest in documentary film. It’s amazing to watch while you’re drawing comics, because you can look up every once in awhile; you just listen and learn things.

Sometimes, I think that nonfiction has more power behind it. For instance, the Darren Aronofsky movie The Wrestler … I thought it was a good depiction of pro wrestling, which is rare. But I remember leaving the theater and being like, “That would’ve been better if it was a documentary about like Jake ‘The Snake’ Roberts.” On the other hand, they did make a documentary about Jake “The Snake” Roberts and it wasn’t as good as The Wrestler, so I guess it depends whose hands it’s in. (Laughs)

Do your ideas start with topics you’re already pretty obsessed with?

Yeah, all of them come from an obsession. It’s kind of funny, because within the last three years, I was diagnosed with OCD. I look back on stuff now, and I’m like, “Oh yeah, this is obsession.” The pro wrestling things were, for sure. I wasn’t an obsessive studier of the history of Tetris, but there was a time in my life when I was an obsessive Tetris player. Also, I feel like I got lucky, because the Tetris story is just a crazy story.

The Andy Kaufman thing also comes back to pro wrestling. When I was flipping through the channels and came across Andy Kaufman documentaries on Comedy Central, the thing that drew me in wasn’t Andy Kaufman, it was Jerry “The King” Lawler. And then I kind of stayed for the comedy.

Cannabis doesn’t focus on pop culture like your previous books. Is this topic something you’ve been interested in for awhile?

Cannabis is more of a lifelong obsession. I was arrested for possession when I was 16. I didn’t see this as an opportunity at the time — it was the worst thing that had ever happened to me — but I got to go through the legal system, being handcuffed, that whole thing.

Wow. What year was that?

This was 1996. And what I found out in my research, actually, was that in 1996 the number of people arrested for cannabis doubled. In 1995 there were 200,00 people arrested for cannabis laws, and in 1996 there were 400,000. So I just got caught up in that. But going through probation and urine tests and seeing how people of color are treated differently from white kids in the middle-class suburbs … I got off probation on good behavior in four months. At the time, I was happy, but you know, in high school kids would get busted for underage drinking, and they didn’t get arrested. Their parents would get called, and that was it. I just saw that as a huge hypocrisy, and since then, it’s never been far from my gaze.

So essentially, you’ve been researching this for years.

Yeah, but it got more intense when I started working on the book. It’s funny, after the Andre book, I was pitching ideas to Calista (Brill), my editor at First Second. I made a whole list of (topics), and cannabis was on there. We never talked about it or anything. After I finished the Andy Kaufman book, Calista was like, “Hey, how about this cannabis book you were talking about a few years ago?” I was so stoked. I didn’t think they would ever let me do a book like that, for some reason. Then it became work to really figure out the story and how I was going to tell it.

Whenever I’m working on stuff, I’m always like, “Where does it start?” I always think of that scene in Adaptation where he’s trying to figure out how to start his screenplay, and he’s like, “Start at the beginning of time!” So then I was like, “Where does cannabis start? What’s our history with it?” Because I think people sometimes think that it was invented by jazz musicians in the ‘30s or invented by the hippies or something like that. The truth is, it goes back to all of human history.

One of the things that I found was in the Hindu creation myth, they mention cannabis. It’s in the Hindu holy book and used in religious ceremonies the same way that red wine is used in a Catholic religious ceremony. So if you think about that … If the shoe was on the other foot and India decided red wine should be completely prohibited across the world and then used their power in the U.N. to make everyone in the world sign on to that, you could imagine what the Catholic people in the world would say about that. But that’s essentially what we did with cannabis to the Hindu population (and) the people of India. We forced them to outlaw this substance that they’ve been using in religious ceremonies since the beginning of time. Then over the course of 83 years, millions of people were arrested and imprisoned all over the world. And it was all because one guy (Harry Anslinger) basically wanted to keep working, and there was an industry behind that to help make this happen. It’s just a huge travesty.

You know, I think about the way that you see cannabis treated in mainstream media — it’s almost always a joke. And it’s just not funny. I lost my sense of humor about it a little bit.

Who do you think is the audience for this book?

I feel like it could be anybody. Cannabis is in the news every day. People are making decisions about whether or not this thing should be made legal, and they don’t even understand why it was prohibited in the first place. I think you need to know that history before you make that decision. I think we’re seeing a lot of legalization bills come through that are still incredibly punitive when, really, this is a wrong that needs to be righted.

It’s not an opportunity to get rich. It’s not “Let’s tax the shit out of it, let’s regulate and create all these things” — even though all of that stuff is good. That’s a side benefit. The real thing you’re doing is to stop arresting people, you’re letting people out of jail, you’re expunging records and you’re not persecuting people for no reason anymore. This is a huge, enormous horrible thing that the United States did to the world.

You may spark action or change people’s minds with this book.

I would hope so. Somebody on Twitter this week was like, “I probably have the total opposite opinion than you do about this book, but I’m still looking forward to reading it.” And I was like, “Well I wrote it for you!”

For some readers, I have a feeling your work is their entry point to comics.

I hope so. I was just at C2E2, and a few teachers came to me and said they keep my Andre the Giant and Tetris books in their classrooms. As I was making all of those books, I was thinking of the audience as adults, and it’s funny to me that, in a lot of ways, the biggest readers of them are teenagers. That’s amazing to me. This kid came up to me at C2E2 that was 16 and told me that he bought my book on Saturday, on Sunday he read the whole thing — and he’d never read a book before! It was the first time he’d read a book.

When I bring up your name to other cartoonists or industry folks, they’ll often say something like, “I don’t know how he works so fast!”

When I bring up your name to other cartoonists or industry folks, they’ll often say something like, “I don’t know how he works so fast!”

Well, there was a long time when I was a workaholic for sure. The first seven to eight years I was doing comics, I was doing like 12 hours a day — no breaks, no weekends, nothing. It was unhealthy. Now I keep a super-regimented working schedule, but I just work five days a week, 8-5. Also, one thing for sure is that I don’t have a second job, which slows people down and can suck creativity out of you. So I’m lucky as hell in that way.

And I just love to work. One of my joys in life is making comics. I feel like the comics round out who I am, and without making (them), I’m not all of who I am.

Would you consider yourself a more confident cartoonist than you were 10 years ago?

Probably not. (Laughs) It’s like, when you make work, you look at it and you’re seeing all your mistakes. It really takes me like a long time away from a piece of comics to then look back on it and see the good parts. It’s like looking at yourself in the mirror: Even when you’re in good shape or losing weight or whatever, you’re still seeing your problem areas.

Considering the success you’ve had in the last few years, I might assume otherwise.

Oh, but the other day I read a review of my work that had a single sentence in it that could be construed as somewhat negative, so that’s what stands out. Such is life of being a creator, I think.

Many artists spend years trying to find their own voice. Do you feel that you’ve found yours? Your work really seems to have evolved over the last few years.

Yeah, I actually do feel that way … but it’s a never-ending search, you know? In the Garry Shandling documentary, they talk about how in his journals, he wrote, “BE MORE GARRY.” He was always trying to be more like who he is and was about unraveling more of who you are and being as true to your real self as you can be. And that’s a never-ending struggle. So I feel better about it, but I’m still working.