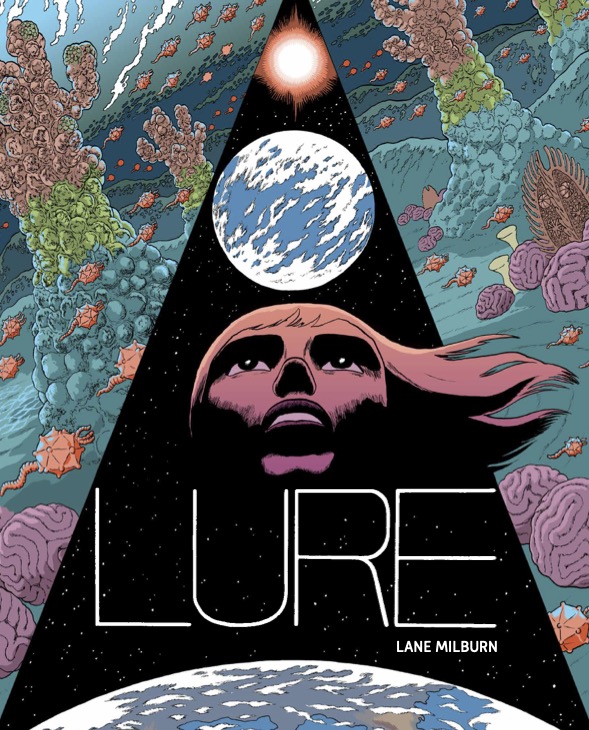

Lure, the new graphic novel from Chicago cartoonist Lane Milburn, follows Jo, a twenty-something artist who accepts an off-world corporate art gig. She travels to Lure, a sister planet to Earth and a vacation spot for Earth’s elites—a trip that takes her from post-art school ennui to existential outrage. The story is a departure for Milburn as well, visually and tonally distinct from his previous book, the 2014 sci-fi romp Twelve Gems. In depicting the complicated dynamic between Jo and Ian, an ethically compromised technician, or in rendering Lure’s alien landscapes, he demonstrates an expanded range as a storyteller across the comic. -Greg Hunter

Lure, the new graphic novel from Chicago cartoonist Lane Milburn, follows Jo, a twenty-something artist who accepts an off-world corporate art gig. She travels to Lure, a sister planet to Earth and a vacation spot for Earth’s elites—a trip that takes her from post-art school ennui to existential outrage. The story is a departure for Milburn as well, visually and tonally distinct from his previous book, the 2014 sci-fi romp Twelve Gems. In depicting the complicated dynamic between Jo and Ian, an ethically compromised technician, or in rendering Lure’s alien landscapes, he demonstrates an expanded range as a storyteller across the comic. -Greg Hunter

Greg Hunter: First, I wanted to ask generally about Lane Milburn the cartoonist. You worked on your latest project a long time, and you’re someone who’s not a full-time comics maker or a gigging artist on licensed comics. How is that work-life-art balance for you these days?

Lane Milburn: It’s pretty good. These days I work four days a week at Trader Joes—that’s kind of how I make my income—and then I have three days off that I dedicate to cartooning. Occasionally I’ll have freelance art gigs come in, but they’re very irregular and very minor—friends’ bands will need some album art. I’ve had many kinds of day jobs in my life, and I’m discovering I do well with ones where the responsibility on me is minimal, the expectations and boundaries are clear, I can get time off when I want . . . That’s been really great.

In terms of the new book—Lure depicts an off-world journey, but it’s clearly grounded in some real-world concerns about the inhabitability of our planet in decades to come, some real-world class dynamics . . . One character even remarks, “It’s like we’re at Palm Beach.” To an extent, I can imagine a version of this story that takes place in some playground for elites here on Earth. So I’m curious about when the trappings of science fiction become useful for you, what they do for you or compel you to do.

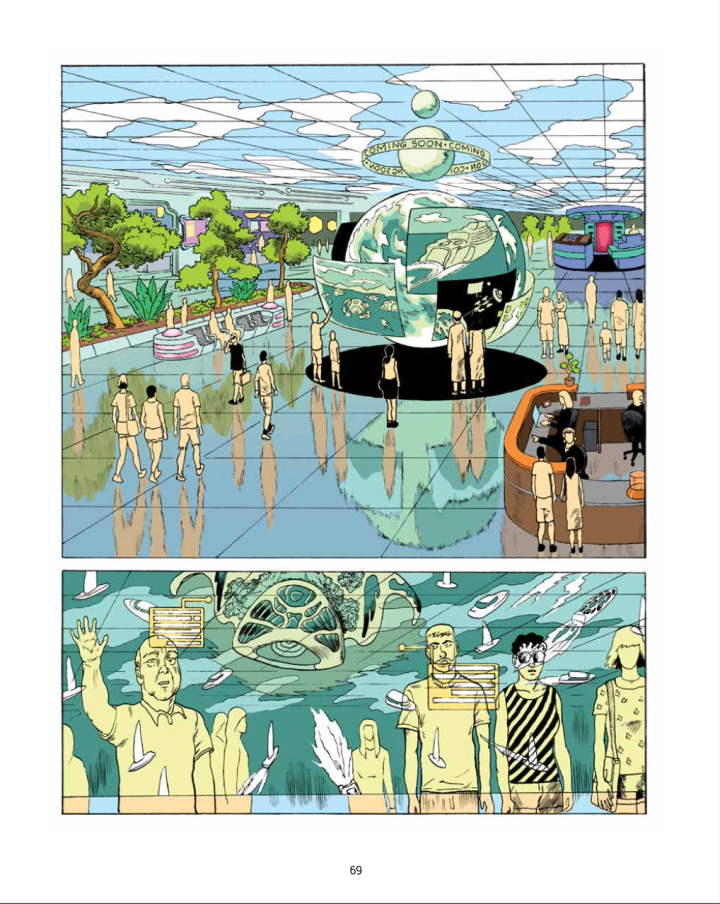

It’s something I think about a lot. I have brought more realism and more autobiographical material directly into this book—considerably more than in any of my previous work. At the same time, I’ve kept some genre trappings, and hanging onto those genre trappings makes the work fun—and therefore possible for me. It’s funny—sometimes conversations around genre or science fiction can tend toward the big ideas, the big questions about society. Money, the future. I’m right there for that discussion, but being a cartoonist also means that you get to be a child playing in your sandbox, and science fiction means that you can draw a bubble-shaped building or alien foliage—fun stuff like that.

In a big project like this, I try to have things that I plan for and look forward to drawing. The genre trappings help me do that, for sure.

Lure has its origins in your earlier, abandoned project Envoy. In that regard, it was sci-fi from the start, in a specific, inherited way. How differentiated are those two projects now? How would you answer the question of “How long in the making was Lure?”?

In its current iteration, I began working on Lure at the beginning of 2016. But if you factor in the prior year, when I was serializing Envoy on Vice.com—I spent about a year on that—the total time is six years. I regard this iteration as being completely different from that first one. The only things I’ve held onto from that previous iteration is that the book stars a young woman named Jo who goes to a planet called Lure. Those were the only elements that I kept.

It was a difficult thing. I had been working on that previous iteration, and I was happy with some of the artwork, but I read over some of the story and it wasn’t working for me. I wanted to step up my writing game. I was working as a graphic designer for Whole Foods at the time. That was a job with a slightly more white-collar color to it than my current job. It was an office job—I’ve had some other strange, corporate art gigs in my time. So I was bringing in some of that stuff, and the current and final iteration of the book is an unusual mashup of realism and science-fiction elements.

Did you have a pretty realized idea of what Lure would be, after that fork in the road and you started going in the direction of what became the published book? Did you have the comfort of the story being mapped out ahead of you, or were you abandoning one direction for the process of figuring out an alternative direction?

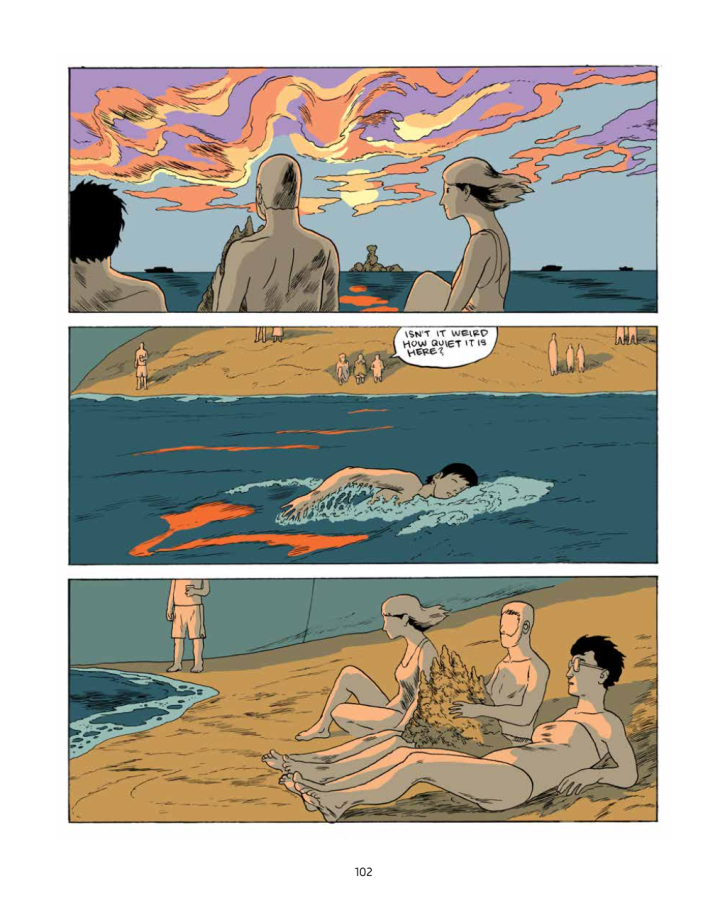

The direction was very unclear after I abandoned that first version. Abandoning a project after a year of work was hard on me, and I wanted to hang onto a couple elements, but it was just those two simple things I described. It took a long time for Lure to take shape. I think that is palpable in the book, and I’m okay with the book having that quality. It has a slowness—a sense of the narrative arc taking shape slowly—and that follows from the long gestation process the book had.

I knew I wanted to create a world. That was clear from the beginning. And the themes of corporatism, art, climate change—those I think about all the time, but they were integrated into the work slowly. Having people close to me look at the project at various stages, that also helped it begin to take shape.

In terms of major shifts—Twelve Gems, your last book with Fantagraphics, was a sci-fi comic first and foremost, I think it’s fair to say, but it would not have been strange for someone to call it a humor comic too. A line like “I’m too pumped to knock” still rattles around in my mind, and the sensibility of that older book is pretty over the top.

Lure, like you’ve said, is more measured in its storytelling. There’s a wit to certain aspects, like the way artists talk to each other, but there aren’t the same kind of laugh lines, and there’s more restraint at work. So I was hoping you could talk to that transition—the extent to which it was a conscious choice.

That was definitely very conscious. It’s strange—it’s hard for me to even put myself in the mindset of the person who made Twelve Gems, because I don’t read my old work, rarely ever look at it. I think the humor and the tone of that book was where I went automatically. To me, it feels like a young person’s creation. It’s funny—the tone was both automatic and yet had come about from years of work, because I did have a few years of cartooning behind me at that point.

The transition into the way I’m writing now was a really big one. It’s the biggest leap I took between the two projects. And it was part of a larger transition in the whole way I thought about my work—everything relating to how I thought about my work. The writing, the restraint, the muted tone of Lure is much more attuned to my personality, my subjectivity, my way of being in the world. The writing is also related to observation, to things I’ve said or would say . . . I gradually just became more interested in writing things that had the character of things I’d heard other people say or were actual scraps of things I’d heard other people say. That came to be the comedic writing I most appreciate: a recreation of the un-self-aware things people say, humor that emerges out of everyday speech, misunderstandings.

Like I was saying earlier about Twelve Gems being a young person’s book, this book represents not only an evolution in my way of working, in thinking about my work, but in my tastes—in humor and everything else.

In terms of still finding pleasure in the work—the pleasures of a more serious work—you referred earlier to the joys of drawing some of these sci-fi structures. And I’d wanted to ask about the intersection of composition with plot and theme in a book like this. Often, when you’re drawing Lure—the planet within Lure the book—you’re drawing a vision of decadence—these ornate structures made for fanciful living. It’s lively imagery with a grim context. So I wanted to know what that process is like—not in terms of what tools you use or anything, but whether or not you would lose yourself in the drawing of things that, on plot level, have some contemptible origins.

Yeah, and it’s interesting that you talk about them that way, because I’m right there with you, with there being a dubious morality behind this place. The thing is, part of the evolution in writing and thinking about my work is also a leaning into ambiguities. In creating Lure the world, this pleasure planet for an extreme minority of billionaires, I want there to be an ambiguity in the sense that I wanted it to actually seem nice, to actually seem pleasurable. It’s not realism, but I wanted it to seem like a place you would want to be. It’s a kind of paradise.

That’s how I was thinking about the composition of the world in relation to some of these themes. It’s funny because I think that so many of the ways in which we are dominated by the inequalities in society are totally invisible. I didn’t want a screamingly obvious satire of corporate greed and evil. I would like Lure too.

On a similar note, Lure has human-made structures, but its own environment, its own fauna. I liked the wordless interlude with the bioluminescent creatures. So I’m curious too, in drawing things not of this Earth—and in getting further away from the Twelve Gems approach, where you’re really riffing on sci-fi tropes—what is your measure for how alien is alien enough, visually? Is that a conscious process?

It’s very conscious, and something I feel unsettled about in my work is what proportion of reality and unreality I want there to be in a book. I’ll probably be wrestling with that proportion forever. But science-fiction imagery, and also psychedelic imagery, comes to me very easily. I can sit down and just do that.

I wanted the world definitely to look alien. I was using for reference a lot of Ernst Haeckel drawings. He was a nineteenth-century Prussian scientific illustrator of microscopic organisms. He would do these incredibly detailed, highly rendered illustrations that were laid out on a page in an incredibly beautiful, decorative way. If you look at his work, there’s just nothing more alien or magical.

If you look at lifeforms that exist on Earth, you easily can discover things that look incredibly alien. Things you see in a YouTube clip or whatever that are not part of your familiar experience. So I was thinking about that. I wanted to create something alien but also with a bit of familiarity. And, in the conception of this book, I was thinking of Earth and Lure as two planets that orbit the sun but also rotate around each other. A while ago, I read Ursula LeGuin’s Dispossessed, and that book is about these two planets that—I don’t know if they have that exact configuration, but they’re close to each other, people travel between them.

So, my idea was that Lure was like an alternate Earth, a nearby Earth, with a different evolutionary timeline. The creatures are crustaceans, so there’s a kind of familiarity—I got into that idea. It also has the feeling of maybe a prehistoric Earth, like a Devonian Earth or something, without the big armored fish or whatever. But I was thinking a lot about those design aspects when creating the world.

What, generally, was most challenging for you as an artist and a storyteller?

What was most challenging for me was, and is, creating plot. Something I’m discovered that I can do, and think this book is evidence of, is create a world and meander around in it for five years. Conventional plot structure, Western narrative arcs, whatever you want to call it—that is not something that comes naturally to me. That was something I really struggled with. I like a lot of fiction that is meandering—meandering is something I enjoy doing in my work, even central to the way this book works. Getting those A-B-C plot things in place is the most challenging for me, setting something up and having a turn.

That’s interesting to me just because of how work intensive comics are. I’m not a cartoonist myself, but if I were, I’d find it difficult to meander in an atmosphere just because of how long it takes to get to the end of a two-hundred-page book.

It’s understandable. And I think the meandering may also be borne out of how, working on a comic, you become habituated to a very high volume of work. And so, at least for me, the meandering becomes possible because I’m being carried along by my routine and my process in a way that allows me to float through the world and not feel like, “Oh god, why am I doing another five pages of this subplot?” or something like that. Getting carried away in the process allows me to produce material but it doesn’t necessarily propel me through plot-point decision making.

Speaking of plot—I’ve saved spoiler territory for the end of this conversation, but we’ll enter it now. You’d mentioned earlier that Lure undeniably looks like a good time. It looks like a nice place. Along similar lines, the character I spent the most time thinking about after finishing the book was Ian. I think it’s because he’s someone who shares certain qualities with Jo and Rachel but who knowingly makes real compromises too. And in the end, he might be the person most readers are ultimately closer to.

I’m thinking in terms of the small concessions most of us make for comfort, knowing what we know, whether it’s running your air conditioning, driving a car when you could have biked somewhere, things like that. I’ll note for the eventual reader of this interview, obligatorily, a small number of companies are producing an overwhelming proportion of global emissions, etc., but still—climate change poses ongoing individual ethical concerns.

Anyway, a reader’s perspective is closest to Jo’s, which makes Ian’s choices feel like a betrayal. Not even “feel like”—it’s fair to say a betrayal is what he does. But it’s still a decision that leaves us with interesting questions. To whatever extent your view as author tracks with Jo’s or departs from Jo’s, I’m curious—what does a person like Ian owe to other people? When it comes to climate change and the interconnectedness of everybody—what is Lure saying about what we owe each other?

I think the moral center of the book lives within Jo’s encounter with Ian. He’s someone who’s moved up the ladder. And yet Jo works for a company that has brought her into the same milieu he exists in, and it’s almost like he’s Jo with fewer moral reservations. He’s someone who had artistic ambitions he abandoned or grew out of. I wonder if there’s something about adulthood in there too. I don’t want to use a cheap term like “selling out,” but he’s someone who exists in this power structure, serving this elite circle of billionaires and doesn’t have any moral reservations about it and has no compunction about doing harm to people he’s been close to if it protects himself and the structure he serves.

He grew out of some of my thinking about . . . I mentioned earlier that I had some other weird corporate jobs. One of them was working for this startup company here in Chicago. I don’t know if you’ve heard of this industry, but it’s called graphic recording. I would have been paid a lot of money to stand on a stage at, like, a Bank of America lecture at a hotel in Las Vegas. I would have been standing there with a giant piece of foam core, and I would have been cartooning out the content of this lecture they were giving in real time. It’s kind of a trend in the business world. This is a job that I had been hired for. I’d had three interviews, and I’d beat out all these other people. The job happened to mesh with my skillset, because I would be doing text bubbles and lettering and little icons in real time as I transcribed the content of this lecture. But after a couple of days, morally, it was weighing on me in the worst way. I came home really upset, trying to put myself in that place.

I guess Ian is someone who would have embodied some aspect of myself if I’d just been able to ride it out and continue working this job, hanging out with Bank of America executives and whatever. I think he speaks to the fecklessness of capitalism—the idea that we don’t owe each other anything, that a good life is an ascent up a corporate ladder. It’s kind of an American ideal, and also happens to be . . . the pinnacle of immorality. [laughs]

It’s interesting, him compared with Jo and Rachel and their immediate boss. But if Ian is where he is because he seems to have no connections left on Earth; and Jo’s boss on Lure, who’s more of a cornball, has family to provide for; then Jo, for her part . . . She ultimately makes very different choices, but first, she makes the choices that get her to Lure. And with her—again, she ultimately makes different moral choices—but her going to Lure might be the least defensible of those three, because it results more from aimlessness, post-art-school malaise. In showing how difficult it is to live your life outside of these systems, the book gives a range of people getting to the same place.

Yeah, with Jo, I agree with what you’re saying . . . I think Jo is also attracted to Lure by the novelty associated with it. She wanted to get this study-abroad grant and didn’t get it. She’s had a sense throughout life that her life is out there, awaiting her somewhere far away. That’s a version of something I’ve experienced. I did apply for a Fulbright grant to study in Madrid at the end of college, which I didn’t get. That had an effect on the course of my life. That was back when I wanted to be a painter.

It’s not one to one between me and Jo, but I think what she goes through is a version of something I felt. And I was definitely thinking about how the complicity is shaded in these different characters. The guy Teddy who works immediately above her is pretty closely modeled on one or two of my coworkers from many years ago, the kind of punk-rock dad who’s also a corporate guy. I’m interested in these shadings, and I’m constantly thinking about how all-consuming capitalism is. I didn’t want to have anyone who was an obvious, cookie-cutter, screamingly evil characters. The billionaires don’t ever really talk in the book.

So, I know what you’re saying about Jo’s decision being perhaps the least defensible. I just wanted to show people wandering into this milieu for a variety of reasons or shadings of the same reason. Definitely needing to feed your family is an understandable reason. And then Rachel, the woman Jo works with, had student loans. It’s almost like a fantasy story where people have all different reasons for going toward one place.