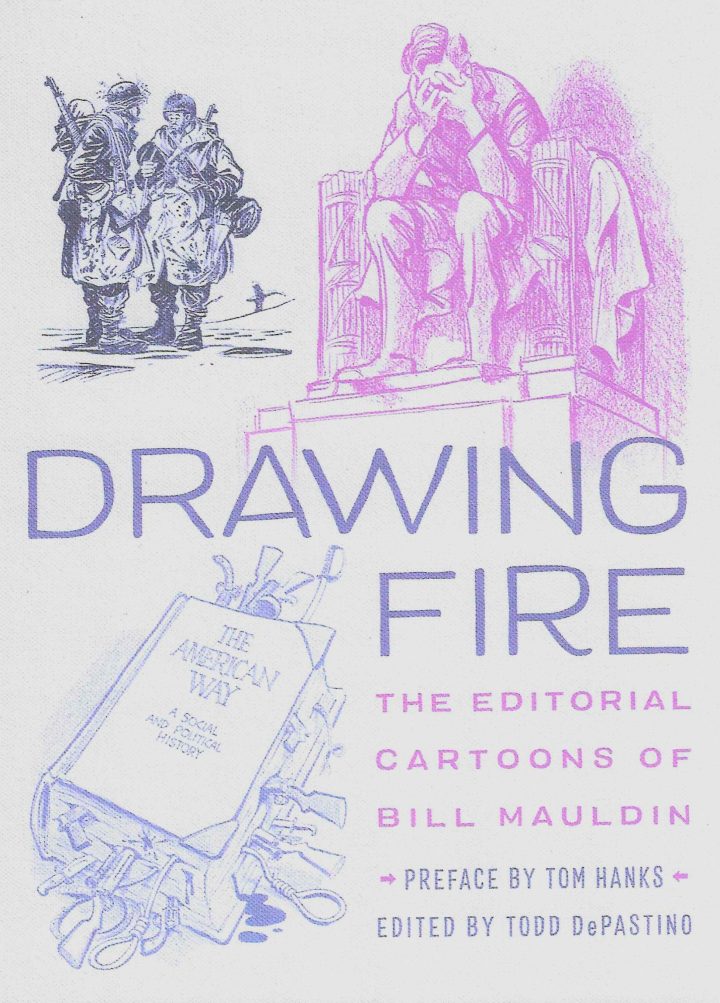

JUST ABOUT EVERY PAGE in the 226 7x10-inch page Drawing Fire: The Editorial Cartoons of Bill Mauldin (2020 Pritzker Military Museum hardcover, $35) has a Mauldin cartoon on it. Just one. Which means his cartoons are given greater display herein than they ever got in the newspapers that initially published the cartoons. Mauldin drew political cartoons for about 40 years; and he drew cartoons about ordinary foot soldiers (“dogfaces”) in World War II as a 5-year prologue. That was the first war he cartooned about; he would cartoon about four more, ending with the first Gulf War.

Mauldin’s cartoons have been published in books before this. The most famous of them was Up Front, in which Mauldin also writes about his World War II experiences drawing his bedraggled dogface characters Willie and Joe.

In the cartoons he drew for military newspapers, he depicted the life of the ordinary foot soldier the way it was. Rained on and shot at and kept awake in trenches day and night, the combat soldier was wet, scared, dirty, and tired all the time; and Mauldin's spokesmen— the scruffy, bristle-chinned, listlessly dull-eyed, stoop-shouldered Willie and Joe in their wrinkled and torn uniforms— were taciturn but eloquent witnesses on behalf of the prosecuted. Through simple combat-weary inertia, they defied pointless army regulations and rituals: they would fight the War, but they wouldn't keep their shoes polished.

Because they so faithfully represented the average foot soldier's plight and proclivities, Mauldin's cartoons were immensely popular with the men in the trenches. And that very popularity was an affront to generally accepted notions of military propriety, but Mauldin never wavered even after the Third Army's legendary General George S. Patton leaned on him. No matter. Another general, Dwight D. Eisenhower, leaned on Patton, telling him to leave Mauldin alone.

By the time the cartoonist met Patton in 1945, Mauldin, a baby-faced youth of 23, was celebrated throughout the armed forces as a man who spoke for the grunts in the field. He even had his own personal jeep (outfitted as a traveling studio) so that he could travel easily to various venues of the battlefield, assembling material that would reflect the realities of war. His cartoons appeared regularly in Stars and Stripes, the famed serviceman's newspaper, and were distributed stateside as Up Front by United Feature syndicate. Mauldin, although he didn't act it, was doubtless as famous as Patton. The cartoonist, in short, stood his ground.

When Mauldin arrived in the European theater of the war, he was no longer, strictly speaking, a rifleman, a frontline foot soldier. He was assigned to division headquarters and worked full-time as a soldier cartoonist, but he spent much of his time out in the field, squatting in dugouts listening to G.I.s tell their stories. Stories about jeeps and rifles and bad food and leaky boots and other primitive conditions.

Maudlin remembered his safaris for accuracy years later in writing The Brass Ring: "I kept learning over and over that real-life experiences were necessary to my drawings. When I begged off field trips during maneuvers and hung around the 'office' more than a few days, my mud stopped looking wet and my pen-and-ink warriors lost authority. If a drawing lacked authenticity, the idea behind it became ineffectual, too.

"This was especially true in the infantry, where a man lived intimately with a few pieces of equipment and resented seeing it pictured inaccurately. Once I drew the safety ring on the wrong side of a hand grenade hanging from a man's belt. It was a tiny thing, and I couldn't find a razor blade to scratch out the detail for a correction, so I was tempted to let it go. In the end, though, I signed my name backward and asked the engraver to reverse the whole drawing. I never regretted it."

Mauldin's drawing style for the wartime cartoons was wonderfully evocative of the ambiance of the dogface's life. He drew with a brush, and his lines were bold and fluid but clotted with heavy black areas, clothing and background detail disappearing into deep trap-shadow darkness that gave the pictures a grungy aspect that approximated visually the damp and dirty feelings bred by the miserable field conditions of a soldier's life on front lines everywhere. Willie and Joe looked like they needed a bath, and so did many of their readers.

The appropriateness of the style, however, was not entirely the result of a deliberate decision. Mauldin was merely adapting to the conditions of his "workplace"— whatever printing facilities the military newspaper he drew for could find as they moved up the Italian boot from Sicily, which is where his outfit, the 45th Division, landed in July 1943. And they didn’t find much that wasn’t damaged or otherwise nearly inoperative.

Said Mauldin: "In wartime Sicily and Italy, engravers' equipment was worn out or wrecked, making it impossible for them to reproduce fine lines or fancy shading. So I drew heavy, bold, contrasty lines that even a cracked lens couldn't miss. The fact that this resulted in an appropriate and distinctive 'style' for wartime drawings was not due to any inspiration on my part: it was simple expediency."

THE IMAGES OF MAULDIN'S REPORTAGE of the raw ironies of battlefield life— relieved, thankfully, by the sardonic sense of humor that found a common humanity alive and well amid the tedium and hazards of combat life— won Mauldin the first of his two Pulitzer Prizes in 1945.

That was the year the book Up Front was published, and it was No.1 on the New York Times bestseller list for 18 months. In the prose he wrote to accompany his cartoons, Mauldin talked about the inspiration for this cartoon and that. He also wrote about life in the military— his life and the lives of the soldiers he knew.

Some of his discourse is amusing in a sort of sarcastic "ain't life funny" way. He writes about the inequities inherent in the military hierarchy: officers have separate latrines which enlisted men can't use, but if the officers' latrine is further away and it's raining, the officers feel no compunction about using the nearest enlisted men's latrine.

The book has as much Mauldin text as it has Mauldin drawings. And Mauldin was no slouch as a writer of prose. The text alone makes Up Front the best book about war ever written. And almost none of it is about combat—because combat is the smallest part of war for the everyday infantryman. War for an ordinary soldier is mostly about waiting and griping.

Mauldin wrote the text for Up Front in just a week, which his biographer, Todd DePastino, the editor of the book at hand, related as follows:

“Ed Vebell [another artist on the Stars and Stripes staff] recalls Bill holing up in a Grenoble hotel with an eighteen-year-old French girl for seven days, never leaving the room, not even for meals, writing all the while, taking breaks only to sleep, eat, relieve himself, and have sex. The telltale sounds of this last diversion were unmistakable to Vebell, who occupied the room below. Every few hours, he would hear the desk chair scraping backward, then footsteps, murmurings, and the sound of bedsprings creaking. Then no more creaking, the feet padding back to the desk, and the chair scootched back into place.”

I wouldn’t dare doubt Vebell or DePastino, but this sounds too good to be entirely accurate. It’s a great story. And it reminds me of a newspaperman’s credo (one of his credos): when the fact becomes legend, print the legend.

Up Front was the first book of cartoons I’d ever encountered. My father bought it, probably in 1945, the year of its publication, and I inherited it, my first first edition. My father bought the book for himself, but several years later—I was a teenager by then— intrigued, no doubt, by the title on the book’s spine, I took it off the shelf and found the cartoons inside. Then I tried to imitate Mauldin’s drawing style for a while.

Contrary to popular belief, Mauldin wasn't with the daily Stars and Stripes for the entire War. He didn't join the S&S staff until the Allied campaign reached Naples in December 1943. His initial cartooning in the service, three years of it, was done for the 45th Division News, a weekly tabloid newspaper.

MAULDIN JOINED THE ARMY in September 1940, before the U.S. was in the War. He was in the quartermaster corps of the 45th Division, which was made up of National Guard units from three other states, New Mexico, Colorado, and Oklahoma. One of the Oklahomans had been editor of the Daily Oklahoman in civilian life, and he decided to start a weekly newspaper for the Division, a venture without precedent on the divisional level anywhere in the American military.

Noticing there were no cartoons in the paper, Mauldin arranged to be introduced to the editor and soon thereafter found himself assigned to the paper on Friday afternoons to draw cartoons. The rest of the week, he continued scrubbing pots and pans and toilets in typical Army fashion.

Realizing that a soldier's life consisted of more than KP duty, Mauldin asked to be transferred to the more army-like infantry so he'd encounter more viable material for cartoons (and escape KP). As a rifleman in the infantry, Mauldin was closer to the experiences most soldiers have. Eventually, he would be assigned to the 45th Division News every day, so he had a week to conjure up cartoons for it.

In January 1944, the famed war correspondent Ernie Pyle wrote about Mauldin and Willie and Joe, and Mauldin's cartoons were soon syndicated to stateside newspapers nation-wide. Mauldin refused to give up ownership of Willie and Joe, though, and in the compromise deal with United Feature, he took a cut in pay as a result.

After the War, Mauldin returned to civilian life a celebrity, and United Feature wanted him to continue with cartoons about soldiers returning to civilian life.

Mauldin wanted to take a year off to adjust to civilian life, but the syndicate invoked the terms of his contract, which didn’t allow any break from producing a cartoon every day. So that’s what Mauldin did.

Under a succession of titles (Sweatin' It Out, Willie and Joe, Bill Mauldin's Cartoon), Willie and Joe shed their shabby uniforms and dressed in mufti. But they didn't look very comfortable. Mauldin's bold brush strokes and trap-shadow shading, ideally suited to depicting the gritty life at the front, made his civilians look like bums. But that wasn't all that was going awry.

Initially, the circulation of his feature doubled, but Mauldin soon found that his approach to cartooning wasn't working in civilian life. He had started by reflecting the returning G.I.'s experience— their anger at shortages, no housing for themselves and their new families and few goods and fewer jobs, and at unthinking yahoos who failed, apparently, to appreciate sufficiently the sacrifices the erstwhile dogfaces had made.

Mauldin’s ire up, he went on to assault segregation and racism, the Ku Klux Klan, and then right-wing veterans' organizations and politicians. While taking essentially the same satirical stance that he'd taken in the service, his cartoons were now seen as "political" rather than "entertaining," and newspapers dropped his feature quickly, saying they had their own political cartoonist.

Mauldin realized he couldn't cope with what was happening to him and be a good cartoonist. So he dropped out for about a decade, writing books, acting in movies, and running for Congress in 1956. Milton Caniff lived in the same district, and the two became good friends. Caniff drew campaign posters for Mauldin, and Caniff's wife, Bunny, was Mauldin's treasurer. But Mauldin didn't win: it was a densely Republican district, and he was a flaming liberal Democrat.

One of the books Mauldin wrote during this period is about his growing up in New Mexico, Sort of a Saga; illustrated by the author but with sketches not cartoons, it may be one of the best books about growing up.

Mauldin wrote as well as he drew, and he eventually produced over a dozen books, all of them illustrated, some being reprints of his political cartoons. He revisited the autobiographical landscape of his youth in the Southwest and his rise to fame in the Army in The Brass Ring in 1971. But with Up Front, his first endeavor in prose and pictures, he produced a classic about men in war.

In 1958 on one of his wanderings through the wilderness, Mauldin dropped in to visit Daniel Fitzpatrick, the celebrated political cartoonist at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and when he learned that Fitz was retiring, Mauldin promptly applied for the job. He got it, and suddenly, Mauldin's liberal voice had a home again. Winning his second Pulitzer in 1959 and the National Cartoonists Society's Reuben as Cartoonist of the Year in 1961, Mauldin continued the battle he had begun in the army. "I'm against oppression," he said, "— by whomever."

MAULDIN WAS PERFECT for a career as a political cartoonist. He could draw anything, and he was eager to take on the establishment. "If I see a stuffed shirt," he would say, "I want to punch it." From which his advice to political cartoonists everywhere follows as logically as the day follows night: "If it's big, hit it. You can't go far wrong."

In 1962, he made an unusual agreement to join the staff of the Chicago Sun-Times, "not as its editorial page artist," he explained, "but as a sort of 'cartoon commentator.'"

He wanted to be on the op-ed page rather than the editorial page because he didn't want anyone to think he endorsed the newspaper's opinions. And he wouldn’t work always in the office. "I was free to say what I pleased," he wrote, "and travel where I wanted, so long as I got my stuff in on time." His WWII experience seemed to be kicking in again:

"It has always seemed to me that a cartoonist who stays desk-bound and does not get out, like any other reporter— or recorder— of events, and sniff the world about him, is in danger of falling back more and more upon drawing elephants, donkeys, Uncle Sams, and other devices of our craft which haven't changed much since Thomas Nast invented most of them nearly a century ago."

Mauldin was away from the office— albeit not far— on November 22, 1963, the day he would produce his most memorable cartoon. He had finished his week's work before noon and went with Ralph Otwell, the paper's managing editor, to a luncheon speech on foreign policy. The speech was never given.

"Halfway through dessert," Mauldin wrote, "the news that President Kennedy had been shot spread through the room."

Soon, they knew Kennedy had died of his wound. Mauldin and Otwell headed back to the newspaper office, but Mauldin didn't go into the building right away.

"He took a stroll around the neighborhood," Otwell remembered, "trying to get over his personal grief. And then he went back to his cubicle. Some admirer had sent him a bottle of Jack Daniels that had been gathering dust in his desk drawer." And before he went to work, Otwell said, Mauldin "reached around his drawingboard, pulled out the bottle, and took a big snort. That's what he told me later."

"I was amazed at how upset I was," Mauldin wrote. "There is nothing like doing familiar chores in familiar surroundings to keep your keel under you. I started working at 2 p.m., one hour after the President had been declared dead.

"What to draw? Grief, sorrow, tears weren't enough for this event. There had to be monumental shock. Monument— shock— a cartoon idea is nothing more-or-less than free association. What is more shocking than a statue come alive, showing emotion. Assassination. Civil rights. There was only one statue for this."

Maudlin drew the now familiar picture of the statue of Lincoln in the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, bent forward in his seat, head in his hands, a perfect posture of grief, an emblem of national mourning.

It was so effective a device that it would inspire a generation of editorial cartoonists. Henceforth, tragedy and death were often symbolized by an inanimate artifact weeping. The most celebrated, perhaps, being the Statue of Liberty, shedding a tear as the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center burned in the distance on September 11, 2001.

"I started the drawing at 2:15 p.m.," Mauldin said, "and finished at 3 p.m.— the fastest I had ever worked. An average cartoon takes three or four hours. I almost threw it away (after all, my week's work was done, and nobody expected this one) because I couldn't get his hair right. No matter what I did with it, it looked more like Kennedy hair than Lincoln hair. This might confuse some people who weren't familiar with the statue. Then I decided that if they didn't know the statue, they wouldn't get the cartoon anyway."

In an unprecedented move, the Chicago Sun-Times published the cartoon on the back page, giving the tabloid an alternative cover.

"Our first edition was on the street at 4:45 p.m.," Mauldin said. "Later I was told that most Chicago news dealers sold the paper with the cartoon side up."

HE CARTOONED for the Chicago Sun-Times for almost three decades. Eventually, Mauldin moved back to New Mexico where he grew up. He settled in Santa Fe, where, for amusement, he worked on old automobiles and a 1946 Willys Jeep, exactly the vehicle he toured Europe with while in the Army. He sent his cartoons to Chicago electronically.

Officially, Mauldin retired in 1991. In a perverse way, his retirement, at last, was forced upon him: pursuing his avocation as auto mechanic, he had dropped a large car part on his drawing hand.

Then, sadly, in the early years of the 21st century, he developed Alzheimers. By the spring of 2002, he was in a nursing home in Orange County, California. He was very frail: he'd been badly burned in a household accident, and his cognitive skills were, mostly, gone. Much of the time, he lay in his bed, not speaking, just staring ahead.

And then veterans of WWII began to hear about him and his situation. They began arranging schedules to visit him in the nursing home, a few vets every day, one at a time in his room. Mauldin’s cartoons had cheered them during bad times in their lives; they would now return the favor and try to cheer up the cartoonist in his bad time.

Mauldin still wasn’t talking, but the nurses there said his eyes lighted up when he had visitors that had once been dogfaces.

Drawing Fire is different than all the other Mauldin books. For one thing, every cartoon is accompanied by an annotation that describes the context for the cartoon. And only a few of the cartoons are Willie and Joe cartoons. All the rest are culled from his long career as an editoonist.

Then there are essays about Mauldin and his cartoons. There are nine of them, starting with a Preface by Tom Hanks and ending with some recollections by Jean Schulz, the widow of Peanuts’ Charles M. Schulz, who was a great fan—and friend—of Mauldin’s.

The two met as a consequence of Schulz’s Veterans Day strip in 1969, Jean said. In that strip, Snoopy, dressed in a WWII Ike jacket, heads over to Bill Mauldin’s house to drink root beer.

Mauldin wrote Schulz a thank-you note, and the two began a correspondence that lasted through their lives.

Sparky (as friends called Schulz) convinced Mauldin to attend the 1999 Reubens convention of the National Cartoonists Society in San Antonio. Neither knew of Mauldin’s developing affliction. But it soon became apparent that something was wrong.

When Mauldin rose to speak, he would often lose his train of thought when relating some favorite story. Mauldin’s first wife Jean, who had undertaken late in Mauldin’s life to shepherd him around, had to finish some of his sentences for him.

“It was sad,” Jean Schulz writes. “Yet it was also wonderful because the audience was still spellbound just to be in his presence. When Bill was struggling to tell a story, Sparky jumped up and told it for him, [drawing on his knowledge of Up Front].

“Then a few other older cartoonists, especially the WWII veterans, also stood up and told more Mauldin stories [thereby masking Mauldin’s inability to finish sentences]. It defused any tension in the room and turned an awkward situation into a fitting tribute to a great man.”

The rest of the Drawing Fire essayists are similarly at the top of their professions. Tom Brokaw, for instance. The others are historians, authors of books about war usually.

Thanks to one or another of the essays herein (or to DePastino’s biography of Mauldin), a mystery about Mauldin’s publication history (that I didn’t even know was a mystery) has been solved.

Long before the publication of Up Front, Mauldin’s cartoons had been collected in book form—at least three times—while the War raged on.

The first of these was Star Spangled Banter, which was the name of Mauldin’s cartoon in the 45th Division News. It was a magazine-size publication, about 40 8.5x11-inch pages in black-and-white. Published in 1944, Banter printed several cartoons on every page, echoing the appearance of Mauldin’s cartoons in the News, where he had half a page to fill with cartoons and sketches, whatever took his fancy.

Later in the same year, more of his cartoons were collected in Mud, Mules and Mountains. This, too, was in booklet form, 46 6x9-inch pages with an Introduction by Ernie Pyle. The cartoons here were printed one to a page.

Then in 1945, a respectable square-bound paperback book appeared—120 6x9-inch pages of glossy paper with a 4-page Foreword by the Editors. Entitled This Damn Tree Leaks, the cover illustration showed Willie and Joe seated under a tree; inside, the cartoons were printed one to a page. It was published by Stars and Stripes, which is where Mauldin had been assigned in late 1943.

The previous collections had been published by the 45th Division News as money-raising projects, intended to subsidize the News.

And that, until November 1, 2021, was what I thought was the whole shelf of Mauldin cartoon books before Up Front. And then on the fated First of November, I dropped in on Rob Stolzer’s Facebook page—where Rob had posted Mauldin cartoons from a booklet, he said, that was entitled Sicily Sketchbook.

I’d run across allusions to a “sicily sketchbook” before, here and there, but the words were often neither capitalized nor italicized. So I wasn’t sure that it was an actual publication. But with Rob’s posting, I knew: Sicily Sketchbook , 28 8.5x6-inch pages, was the first of Mauldin’s cartoon collections, published in 1943 shortly after the 45th Division landed in Sicily. And it, like the next two collections, was intended to raise money for the publication of the 45th Division News (the mystery that I didn’t know was a mystery—why the collections were published).

Mauldin easily ranks in the top ten American political cartoonists of the 20th century. He's in that pantheon because he hit his subjects hard, pulling no punches in presenting his opinion, and because he did it by yoking words to pictures for emphatic, memorable statements that were often powerful visual metaphors.

But with Willie and Joe, Mauldin did something more: he created myth. At least a score of the cartoon images of Willie and Joe are iconographic, imprinted with every wrinkle and whisker intact into the cultural consciousness of American popular arts.

Hereabouts, to round off this review properly, are several of Mauldin’s most famous cartoons, and a couple of my favorites. Not all of them are in the book.