The following article features explicit pornographic images.

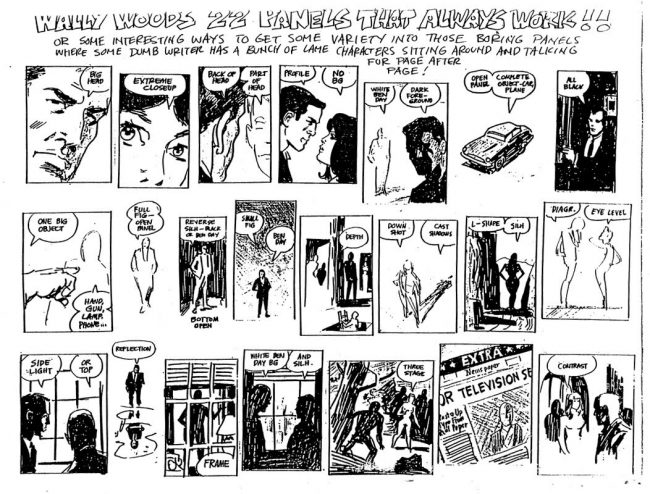

As his era recedes from the present, Wally Wood occupies a precarious position. Once regarded as a pantheon figure whose importance was self-evident, his iconic status has diminished over the current century. Wood was an all-time draftsman with a telegraphing individual style that reads as the culmination of an idiom that a huge number of early comic books derived their visual identity from. Wood evoked Prince Valiant's Hal Foster with greater understanding and brilliance than any of that strip’s countless imitators, but also went beyond mere homage, sanding down and sleekening Foster's baroque ornateness into something lean and nearly mod. Seeing a style the comic book industry was literally built on shitty imitations of both skillfully echoed and cannily refined can feel revelatory, like the crude oil that "comic books" as a popular image runs on turned to jet fuel. It goes beyond mere drafting; Wood understood his form, treating panel breakdowns like architects treat joists and beams. His later career locks in on finding a simple solution for comics, a pictorial lingua franca suited for as wide a use as possible. Wood's (in)famous "22 Panels that Always Work" guide is an ultimate expression of a search for grace in utility. He elevated the pedestrian content of his work by diligently streamlining form, at his best creating imagery that seems to speak to a stylistic core of American comics in sum (1).

The "22 Panels" guide also points up the repetitive sameness of the stories Wood yoked his skill to, and the emphasis his working environment placed on production over innovation. In the pulp-birthed, self-censoring, comic shop-bound, fundamentally stagnant mainstream comics industry of the late 20th century, cosmetic innovations such as Wood's were enough to garner seemingly permanent regard - especially, crucially, when works by any artist who wasn't currently employed on a monthly periodical were rarely in print. Before the trade paperback became a universal currency, with the reading public's access limited to what a few superhero publishers spotlit every week, one or two reprinted fragments of skilled artists’ work were often forced into representing their entire careers in the popular imagination. Some tantalizing installments of a long-ago serial, or a few anthology shorts that caught the popular imagination, when added to in-print praise from one's contemporaries, could build a minor legend.

Today, when books tend to stay in print as long as they sell, and reprints are as fertile a ground for publishing as new work, has knocked some rose from people's glasses. With whole career arcs available to readers, and a greater diversity of content and approach on display than ever before, yesterday's legends can easily be digested and taken as read, rather than slowly tracked down back issue by back issue like white whales, the picture of their true import only piecing into focus over the years. Too, the bar is higher now. Some exceptional Daredevil issues don't go as far as they once did when a century of great works from every continent are being proffered one by one. All this is in aid of saying: Wally Wood was a great artist, but he isn't that great to read.

Wood's career spans an era from the imperial phase of the comic book format to the infancy of the "graphic novel"; a time when the short form wasn't merely dominant in American comics, but monolithic. Few are the works made for the 20th century’s periodical magazine serialization which carry a lasting foothold in today's book-focused market; everyone can name the ones that do, because they're the ones said market was built on reprinted collections of. Wood made a career illustrating and occasionally writing 6-to-24-page shorts for an industry that was starved of talent and amnesiac in its presentation of itself to the buying public, one in which superior visual treatments of rote content could legitimately elevate a book to a rarefied tier of relative quality. There's undeniable power in his drawings, and that power will always have a place in comics history as something that had a wide and lasting influence. Said influence is waning these days, though, with most action comics having moved from Wood’s naturalism to photo-referenced, backgroundless “realism”. And the times Wood worked in dictated that he didn't leave us much to chew on that the form's collective memory hasn't already digested. There's no lasting, revelatory Wally Wood comic because he didn't work on any stories that were even very good.

If I had to pick fragments that embody how I see Wood, they'd be the "22 Panels" cheat sheet, something only a true and truly frustrated craftsman could have created - and the end that his truly depressing life story as a hack among hacks in a predatory industry stumbles to: alcoholism, sudden physical decline, suicide. It's tough not to see Wood as a human talisman of the midcentury comics industry's sins, a benday-dotted Lear. "This month: the greatest talent of them all, denied a place to work in comfort, driven to the bottom rungs, and left embracing death!" *BANG* *GASP*! Too, there is a legitimate darkness to Wood's work, which is meticulous and finely wrought but often stiff and strangely void of warmth, stripping away layers of detail the older its artist gets - hitting deadlines, hitting deadlines, racing, losing, as the clock ticks ever louder. (2) Couple the work with the merest fragment of biography and it's tough not to feel an immense dissatisfaction barely out of sight on every page. Reading Wood as an admirer forces one to question the attitude common to comics that paints the creation of quality work under a predatory system as a triumph over adversity. Does fetishizing something formed by an inherently abusive mandate also fetishize the abuse itself? It's a thoroughly depressing headspace to enter.

If I had to pick an actual book to typify Wood, I might go with Fantagraphics' recent release Cons de Fee: The Erotic Art of Wallace Wood, a collection of short pornographic strips done outside the bounds and on the fringes of his era's comics industry (3). This is a flawed compendium of exhausting, exhausted work that nonetheless manages to do some heavy lifting in its portrayal of Wood's increasingly torpid career arc and the evolution (and subsequent devolution) of his style over the years. It also trains readers' focus on the haunting emptiness that flits around the edges of his panels, managing in its sheer banality to put across some of the exasperation and futility its artist must have felt having to actually make this stuff.

Fantagraphics has already mined a similar deposit of Wood's career with deluxe re-presentations of Cannon and Shattuck, strips produced for overseas military newspapers' audience of enlisted men, free of the comics industry's omnipresent censors. Though their quotient of tits and fucking is preposterously high, these are resolutely action comics, all thrust and no release. They meet a standard of quality as high or higher than anything in Cons de Fee, which is perhaps to be expected since they're right in Wood's gunpowder-and-brawn comfort zone - but their trackless emptiness still echoes loudly. I quit Cannon after a not unenjoyable hundred pages or so (encompassing what I'd estimate to be a few hundred murders and a few dozen sex scenes), once the third or fourth adventure's bad guy was revealed as an incognito Adolf Hitler. With a creator who'd so clearly thrown his hands up, how could I not? There isn't much to be learned from Cannon, I suppose, no clue as to what powers its frenzied exhibition of sheer, thin, perfect eggshell surface.

Cons de Fee, a collection of low-profile, low-paying porno comics, with drawings of fucking that didn't even have to be good in order to fulfill their single consumer requirement, offers a chance to go deeper. Wood's drawing always clearly hungers for the erotic; in every era of his career a drive to do something not just pretty but sexy is obvious. This impetus was almost always stymied by the industry he worked in, however. Action plots demand conflict in much greater proportion than sex; the Comics Code Authority's censors took care of the rest. The violence Wood's better-known work almost exclusively trades in obscures a mysterious stillness, something enigmatic that seems to wait just beneath the froth of its content. Can Cons de Fee, which foregrounds something softer and more pleasurable - something at its best transcendent - show a naked side of its artist that the fatigues and spandex and spacesuits of his career highlights hid? That was my hope, and while the book doesn’t deliver precisely that, it’s illuminating nonetheless.

Cons de Fee’s framing is sorely lacking. Its chronological publication history is useful, but editor J. David Spurlock’s fanboyish supplemental writings are frankly embarrassing – especially coming from a publisher that has frequently provided a considered critical lens through which to view the works it presents. For readers unconvinced of Wood’s abiding genius, or even fans curious why this particular material warranted lavish hardcover reprinting, there is nothing. No analysis, no consideration of historical context or merit relative to other such work done in the overlap of comics and men's magazines, no insight as to what any of the material meant to its creator or why it should mean anything to anyone today. What you will find is the table of contents’ chronology restated as a series of complete sentences, a bewilderingly detailed anecdote on the creation of a 5-page spy spoof “historic comics milestone” called “Pussycat”, and the revelation that Spurlock’s own biography of Wood was nominated for an Eisner Award in 2007. The brief Wood bio that concludes the book is as bad, rendering its subject’s life as unfeelingly as any Cannon episode, signing off with a twist ending as “the gun-loving ex-GI with the mischievous glint in his eye decided to check himself out of this world.” Who needs insight when this case is closed?

It’s a shame, because the material itself could use a road map. It begins simply enough, with a collection of the cheesecake gag cartoons Wood dashed off for Playboy imitators in the 1950s. These are rote and uninspired, rendered in the wispy washes and gouaches common to their idiom, miles from the bristling, polished ink burn of their artist’s overwhelming work for EC Comics a few years previous. The 1960s comics for similar venues that immediately follow are indebted to Playboy as well, specifically former Wood collaborator Harvey Kurtzman’s "Little Annie Fanny": dialogue-heavy parodies of James Bond and Disney that ladle on lavish detail and bare skin without showing any actual sex. This short section of the volume contains a few really good drawings (a nude shot of Snow White's wicked queen voguing in a mirror, pose and reflection rhyming perfectly from a tricky angle, testifies to the plain superiority of Wood's ability), but its value as anything but representative midcentury smut is basically nil.

It's not until the '70s, when the comics marketplace had been opened up somewhat by the underground comix revolution and publishers' subsequent, usually harebrained attempts to ride its coattails, that things get interesting. A collection of Wood's three-color covers for the notorious Screw magazine see him producing gag imagery far more suited to his sensibilities than the weak Hefner imitations that open Cons de Fee. Liquidly rendered, alluringly colored, and legitimately weird in their "humor", the best of these drawings have a verve that the comics material they appear alongside never matches. A short from warhorse underground anthology Slow Death sees the artist taking his professional frustrations head on with the story of a struggling cartoonist whose rage-based superpowers make him perfect for a sideline as a porn star. It's stupid stuff, but telling nonetheless, and seeing Wood bend his style toward the over-rendered, horror vacuii bigfoot idiom of the undergrounds (one his own 1950s work provided a wellspring of inspiration for) is interesting, as is the echo of Wood’s influential Mad Magazine short “Superduperman”.

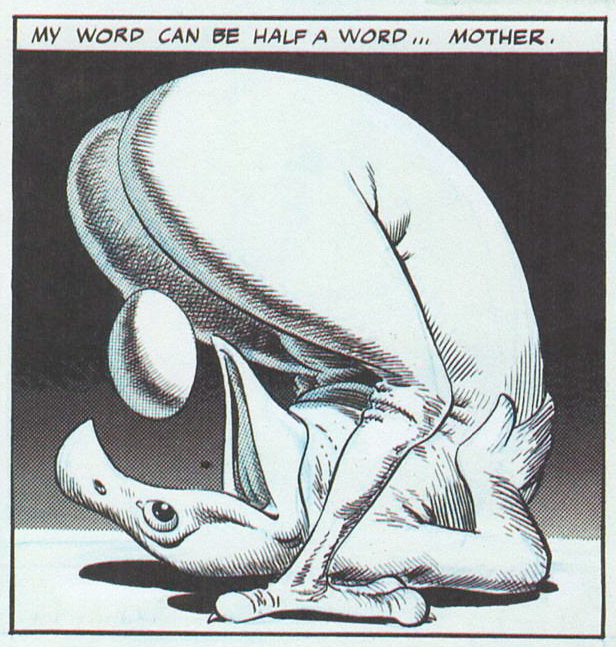

If Cons de Fee has a centerpiece, it's "My Word", a 3-pager published in Big Apple Comix - nominally an underground, but put together by a cohort of mainstream comics mainstays and hangers-on, as edited by longtime Marvel admin Flo Steinberg. "My Word" parodies Wood's own "My World", a cutesy but well-remembered EC short that renders the science fiction genre as a living, breathing environment for devotees to opt into as an alternative to reality. Twenty years on from that starry-eyed lark, Wood renders the opposite side of the coin, conjuring his New York City home as a stinky, venal, and perverted wasteland in which even decadence lacks the ability to move anyone's sensibilities. I've rarely seen a more absurdly sad rendering of despair than a sequence of two tiny panels picturing a woman straining forward to lick her own pussy, a caption next to her moaning "You must love yourself before you can love anyone else, but how many people really can?" and a guy sucking his own dick, reading "Honestly, did you ever try to see if you could? I asked a wise man, and he replied, 'If I'd been able to, I'd never have discovered girls!'"

"My Word" is, if anything, more shocking in the context it's given here than one imagines it would have been in Big Apple Comix. Amid a collection of baldly explicit porn, creator speaks directly to audience not of freedom or pleasure, but of nausea. We get a sense of its author's unease with what he's doing, which probably doesn't matter anyway because the world's already too corrupted for reservations to make a difference. This feeling is elaborated on in Cons de Fee's final story, the appealingly dashed-off "The Sexual Revolution", which reads exactly like what it is: a horny old man's profound ambivalence about the changed world he finds himself in. Wood bemoans sex education and the lifting of obscenity laws, a pornographer halfheartedly imploring his audience to think of the children and turn back toward the morality of his own youth or be "faced with the prospect of an entire generation gazing stupefied in admiration at the twitching of their own hairy assholes". Genuine distaste is unusual to see in the pornographic works of our sex-positive age, but it's unmistakable here. The question to untangle is whether Wood's dislike is greater for the work he's doing, humanity as a whole, or himself. Either way, "My Word" is the best looking thing in this book, its brevity and callback to a career-defining moment pulling a vintage performance out of Wood, however embittered. "The Sexual Revolution" is the closest thing to a key to the rest of what's collected herein: we're seeing the master in a mode more mercenary than masturbatory, his disgust for the jack-off material he's making at least as significant a presence as said material's allure.

After "My Word", both Wood's increasing ill health and his case of who-gives-a-fuck-itis swim into focus as the pages pass. Once dense and dialogue-laden, the layouts open up to a few panels per page; once obsessively rendered and cast in detailed tableaux, the figures simplify, stiffen, and increasingly float against backgrounds either blank or pasted over with zipatone and a few stray perspective lines. There's real weight to watching this process occur, both biographical and historical. You can follow Wood's further streamlining of his own streamlined-Foster style, his drive for a simpler way ever more apparent. You can also see that drive as the practical necessity of a low-paid journeyman artist more than a virtuoso's passionate endeavor. If Wood's 1960s simplification of his eyeball-wrinkling '50s work reads as a canny veteran's embrace of a graphic approach and the limitations of his printing process, at some point in the '70s he overbalances and starts to lose what made him special to begin with.

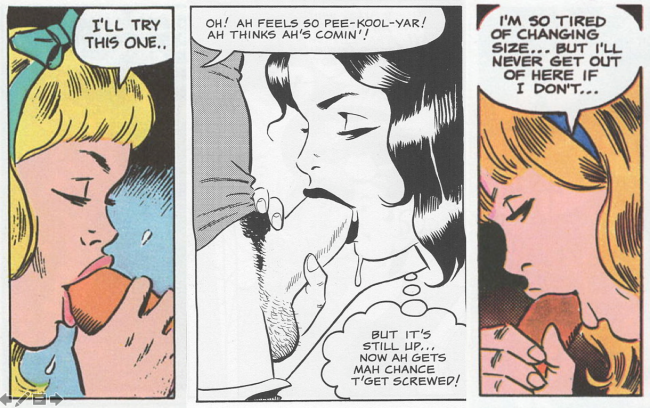

As the stories wear on, both their content and their roteness become progressively more obscene. A second Snow White parody, not as effective or pretty as the first, flickers by without leaving much impression. The frustrated-cartoonist-into-superhero-who-fucks story also gets a second airing, one so perfunctory it never made it past Wood's pencils to the inking stage. A string of newspaper comics sexifications have worth as exercises in style, especially the Prince Valiant one's sideways homage to Wood's master Foster, but none's visual power equals that of its source material, and seen in rapid succession their mockingbird charm goes stale. A bit livelier are "Malice in Wonderland" and "The Wizard of Ooz", a pair of multi-part full-color serials that are notable for mining the same kids' book source material Alan Moore did in Lost Girls. Wood's writing, surprisingly enough, is what provides these with the weight they carry. Their punning dialogue, rhyming lyrical interludes, and knowing references to original versions both cinematic and literary call Moore to mind quite forcefully, parodic sources aside. Notable for less positive reasons is "Malice in Wonderland"'s featuring of precisely zero consensual sex acts. The endlessly repeating rapes both here and elsewhere in the book are played for laughs in a manner that anyone who's ever seen a vintage cheesecake cartoon will have no trouble calling to mind, yet "Malice"'s insistent reenactment of them breaks through familiarity to become something genuinely unpleasant. It's difficult to keep reading by the time the book reaches this point.

So far I've been discussing Cons de Fee as a collection of narrative or publishing tropes, or a chronicle of its artist's career, without really touching on the impression that reading it makes. Part of this is because it's truly one of the most boring comics I've ever read. It's almost (almost) fascinating as such. For an artist whose erotic imagination held such visible sway over his commercial work, to the point that rendering drapery over female figures during his ‘50s golden period appears almost to have caused him pain, Wood's actual erotic comics are stultifyingly one-note. They read like the work of a preternaturally talented grade-schooler who's seen his dad's Playboys and knows what they look like under there, but can only refer to a few stock stag-film images of what actually happens during sex. Identical slim-hipped, vacant-eyed, huge-titted female figures lie on their backs, pull their knees up to their chests, let them spread open again and again and again. As soon as the era's publishing mores allow, studs alternately brawny and scrawny but with identical Magnum cocks, kneeling between the figure's legs like sprinters at the starting blocks, execute the same plunge again and again and again. A few different angles of rigorous thrusting splay out over a page or two, then things conclude with a sarcastic one-liner, or a brawny cock parting identical pouty lips in the same neck-up shot of what if any of this even felt real would be the toothiest blowjob of all time. Once in a while someone eats a pussy for a panel, or a second guy or girl appears to overlay one of the stock poses we've already seen dozens of times onto a combination of the same. It'd be a stretch to say Wood uses 22 different panels to illustrate all the sex acts this book contains. It feels like maybe half that.

The effect of this is profoundly, upsettingly numbing. Wood's wielding of craft is rendered powerless: no artist could have imbued this collection of material, taken as a whole, with any frisson. The parodic nature of every single story is a key to the artist's attitude: here, sex is both something to be laughed at and something that soils, debases. The positions and permutations change slightly, but the overwhelming feel of the book is that of one single unceasing missionary position fuck, a soulless emotionless passionless oil-derrick pounding that never ends or changes, each thrust identical to the next and the last in force and depth and duration, soundtracked with an unamused, sneering "ha ha". As a body, these stories render not just sex but the erotic in sum as a pleasureless yet all-consuming hunger that can never be satiated. It's not that eroticism requires romance or creativity or desire or affection or obsession or transgression or exploration, but Christ, it's gotta have at least one of those! To say Cons de Fee is masturbatory is an insult to that practice, because here there is no fantasy or build, just repetitive motion, then an end. It's a terrifying referendum on the dullness of straight male erotic life in the Playboy era, a piercing shriek for the more varied and creative imaginings of sexuality that (somewhat) more equal representation has brought to comics and everything else in the years since Wood's death. A trip to Pornhub or down this week's superhero new release wall provides a rainbow's spectrum of diversity by comparison.

So I pity Wally Wood, who this book depicts jettisoning unasked-for flourishes of creativity one after another, chasing a single ossified image of male heterosexual power over a frozen female body in ever-tightening concentric circles until there's nothing left but the end. Cons de Fee is so utterly draining that it's impossible not to view the suicide of the man who made it with a touch more compassion once (if) you make it to the end. To be a considerable talent in a world with no need for such must have weighed heavily. And yet...

And yet this book still reflects a world made for Wally Woods, where straight white gun-loving ex-GIs could obtain a lifetime's paying work in their field of choice, continue on propped up by assistants long after whatever fire burned in them for it had died, and be well remembered at the end. A world where one single, frighteningly subjective picturing of sex, the most varied and variable of human experiences except perhaps for art, not only could be but was rendered to the world at large as a short set of peepshow images that begin again at the beginning when exhausted. As the only option. A world where nothing was exchanged or mutual, where neither pleasure nor consent existed. The paucity of Cons de Fee's supplemental material is ultimately forgivable, because it digs up the most indelible image in this whole thing, a photo of Wood dashing off a portrait of a cringing Playboy Bunny at a Cartoonist's Society function some swinging '60s evening. Wood, head down and captured in profile, is tough to see, but he looks satisfied with what he's doing. The portrait carries a hint of its subject's likeness, but looks more like the same mascara'd, vacant face we've seen attached to any number of fashionable hairpieces and pin-up bodies throughout this volume. The unidentified Bunny looks like she just really wants to get the fuck out of there.

__________________________________________________________________________

(1) In this Wood is not at all dissimilar to his contemporary Alex Toth. While Wood pared down Hal Foster, Toth's style cuts every ribbon of faux-cinematic fat from Milton Caniff and Noel Sickles. The parallels don't end there: Toth too trained a laser focus on formal elements of staging and composition, slowly unearthing a set of comics-native pictorial solutions that remain very much in use today. And Toth too had a long, winding career that ended in personal frustration and a lack of truly superior (or even like, interesting) stories. He's probably been better served by the reprint market than Wood because his corpus is composed of all-ages pabulum rather than adult pabulum. But for me at least, his most iconic, lasting works aren’t comics but the character model sheets he illustrated for Hanna-Barbera Productions' animated series; another parallel, this time to Wood's "22 Panels" guide.

(2) Austin English has written more fulsomely on the strange void that seems to lie at the heart of Wood's art; his words can and should be read here.

(3) Tied for first place in my personal pantheon of Wood comics is 1965’s much sunnier Daredevil vol. 1, #7, which showcases the artist at the height of his powers, a master of illustrative detail beginning to simplify his style in a very appealing manner. Its more iconic panels whisper of an alternate history in which Stan Lee embraced Wood as an equal to Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko rather than driving him away; one in which Wood could perhaps have had the stable home and classic run of comics that his post-EC career always lacked. Even this fantasy only kicks Wood's total disillusionment further down the road, however... look at how Kirby and Ditko ended up, after all. Comics!