He was a patriarch and a diehard, one of the paper world's genuine tough guys. "Le John Wayne du neuvième art", as one obituarist wrote. When he died on Monday night of a heart attack, Alberto Aléandro Uderzo was 92. He had survived leukaemia (2011), a lung operation (2017) and a serious hip fracture (2018). Yet waking up to his absence on March 24, France was struck by an almost physical shock. With René Goscinny, who died four decades back, Albert Uderzo had created … Astérix. There are just two equivalents: Mickey Mouse and Tintin.

What Goscinny and Uderzo left is more than a legacy – it's an entire culture. In 1996, the Briton Alan Riding tried to decode it for readers of the New York Times. Its story, he wrote, essentially never varies. "It revolves around a little Gallic village on the Brittany coast that is holding out against the Roman invaders in the year 50 B.C. Four Roman camps have long besieged the village but, somehow, the legionnaires are always out-maneuvered by the hapless Gauls. Being hapless is of course part of the joke. The idea is that, like the French, the Gallic villagers spend their time eating and arguing. But when threatened, they unite and magically (thanks to a magic potion) defeat the enemy."

Certainly Astérix does contain Gallic warriors and Druid magic, just as it does a small dog and endless battles. But any focus on plot and personnel buries the lead.

As President Macron wrote in his personal tribute, "The real 'magic potion' was that ink in which Uderzo dipped his pen to draw … 'Our ancestors the Gauls' may no longer be a formula our nation's school books believe in. But faced with his Gaul, picturesque and larger-than-life, we're seized by our affiliation to these kindred souls, with their scratchy moustaches and their golden scythes. What Uderzo celebrated so untiringly was the French way of life, a world where the bounty of the word and table has pride of place, but so do solid values: altruism, faithful friendships, struggle and togetherness. His image of the Gallic banquet is its most dazzling portrait: fine food and beautiful union under infinite stars."

The launch of any Astérix album is a national moment. A new book appears everywhere – even in supermarkets – and it always tops the sales charts for months. To date, Astérix has sold almost 380 million books (Tintin, by contrast, has shifted 240 million.) The stories exist in 111 languages. But what Macron's getting at, and what the nation feels, isn't those statistics and sums. It's a profound history of culture, images and exchange. Nor is it merely French. It's also European – via the boomerangs of Manhattan humor and a Hollywood built by Europe's émigrés.

Uderzo's Italian father was a woodworker, who liked to play his flute of a night. Wounded in World War I, he settled in France in 1922. Alberto was one of five siblings, named after a brother who had lived less than a year. He came into the world with two six-fingered hands which, although surgically repaired within weeks, now seem like an omen. The boy's elder brother and sister had been born in Italy; a younger brother and sister would – like him – be born in France. Their childhood looked something like an early Sempé drawing. Alberto wore a Basque beret to school and wrote on a slate with chalk. He grew up in Clichy-sous-Bois, a poor suburb nine miles to the east of Paris.

From an early age, Uderzo longed to be … a clown. This vocation came to him via a colorful poster that advertised the Fratellini Brothers' circus. "Their act had three stars, but the real prankster – the clown with the big red nose – was my favorite. Because he was played by Albert Fratellini, it seemed like destiny!" he said in 1999. Just as they couldn't afford a pet, however, the Uderzos lacked the means for him to see the circus. His imagination "made up the difference".

Uderzo's childhood always remained a vivid touchstone. He could remember reading Mickey Mouse strips in Le Petit Parisien – before 1934, when the Journal de Mickey appeared. He remembered watching his brothers Bruno (seven years older) and Marcel (seven years younger) as they sat drawing. He also remembered the insults all Italians endured, the kindest adjectives being "oily", "dirty" and "lazy". Many of their neighbors saw called the boys "Macaronis", and accused them of coming to steal jobs from Frenchmen. This soon led Alberto to become "Al" or "Albert", Uderzo. But in his family, and to Goscinny, he was always known as "Bébert".

In 1934 Uderzo's parents became French citizens – something they had tried to do since 1922. To their surprise, only this actually made their French-born children French. "All that time I was learning about my 'Gallic' ancestors," said Uderzo in 1999, "when, in fact, they were Romans up until I was seven."

One of the artist's memories was the first time he drew in public. He was seven when his teacher asked her class to illustrate one of La Fontaine's fables. Albert's sketch so impressed her that she took him straight to the principal. He rewarded the boy with a box of watercolors. No one but Albert's mother knew he was color blind.

It was never a debit. The would-be clown devoured children's weekly illustrés, weekly magazines like Robinson, Hop-là!, L'Aventure, Hourra and Junior. By the age of 12, he was "suffused" with American comics. Then, in 1938, his family moved to Paris. Albert's brother Bruno, now a mechanic, was convinced his sibling had real talent. So Bruno dragged him to the office of the SPE, the Société Parisienne de l'édition. The SPE was a publisher of children's weeklies but they also handled women's magazines. Although Albert was still in short trousers, he became an SPE employee.

At 13, he was lettering comics, retouching photos and repairing graphic mistakes. Within six months, his first drawing was published.

One of the SPE's main artists was the versatile and prolific Edmond-François Calvo (1892-1958), who was saluted this year at Angoulême. Calvo became famous as an animal artist. But he started with caricatures for Le Canard Enchainé. He was – like Uderzo's own father – a gifted woodcarver. His great work is La Bête est morte ("The Beast Is Dead"), which was created in wartime, under the German occupation. La Bête's two volumes describe the war using animal characters. In it, the Germans are wolves, the Britons bulldogs, the Americans buffaloes, the Italians hyenas and the French rabbits, frogs and squirrels. Published three months after the liberation of Paris, La Bête still stands as a landmark. Two of its frames are among comics' first-ever references to the Holocaust.

When Albert arrived at the SPE, his family was living in rue de Montreuil. This is a part of Paris' 11th arrondissement, a traditional quartier of working class artisans. Calvo lived at Porte-de-Montreuil, two miles further east. Oblivious to the details of blue-collar geography, Albert's boss assumed the similar names meant that one was near the other. Since Calvo was habitually late with his art, he asked Uderzo to fetch the boards on his way home. Doing so meant, in fact, a four-mile journey.

But Uderzo placed Calvo's art on a level with Disney's. "So I never told anyone how far it was. I was beside myself at meeting such an artist. In fact, Calvo turned out to be even more. He was also a marvelous man, generous and funny and willing to advise this kid who just turned up at his door. After the war, he had these huge problems with Disney – which was really shameful. His style was hardly plagiarized. It was very personal, painstaking and meticulous. Not only did he have a big effect on my work. After the War he helped me a lot, giving me introductions and advice."

The young Uderzo was hungry in more than one sense. SPE staffers, many of whom were women, made sure he attended all their special events for young readers. At one of these, held in the Grand Palais, Albert recalled being served a plate with "almost half a chicken". But he had no idea how to deal with such a portion. Worried that his knife would slip taking it off the bone, the insecure youngster simply went hungry.

War and the Occupation brought more hunger. Along with Bruno, Albert fled to Bretagne – avoiding deportation to Germany and civil labour. Eventually, threatening visits from local officers split them up. Bruno went into hiding; Albert snuck back to Paris. But, despite the want and hard work, the Breton spirit left its mark on him. He still had praise for it six decades later: "There were very long hours of labor and little to eat.… It was just potatoes, always just potatoes. Yet the people greeted us with open arms. They were profoundly warm, with a wonderful sense of humor. I've always been happy Astérix is one of them."

After the war, Uderzo briefly worked in animation. His boss was Bolivian, his two artist colleagues Breton and Indochinese. He was an intervalliste – drawing the stages between a movement's start and finish. This quickly put an end to his animation fantasies. It was, he realized, "just like work in a factory". Uderzo was rescued by a small ad in the papers, which announced a publisher's comics competition. The winning artist album would see Chêne publish his album. Uderzo mailed in a strip called Clopinard, about a one-legged Napoleonic veteran.

When it was accepted, the shy youth presented himself. How much, he asked, was he going to be paid? The answer was five thousand francs. "When I went home and told my father, he leapt out of his seat. 'Five thousand francs for what? For each page or for the album?'… He forced me to go straight back and ask. I was so shy I was almost paralyzed. When I finally got the words out, there was an endless pause. But then they said, 'OK... then let's make it five thousand a board'."

It was the start of Uderzo's business skills, later to become so legendary and controversial.

Albert's intentions, however, were again upset. This time the problem was his military service. Starting in 1948, he was dispatched to Innsbruck, Austria where he served in a tank brigade, the Fifth Regiment of Dragoons. When he returned in autumn of 1949, most of his former magazine employers had vanished. Albert was so desperate, Bruno taught him to drive a truck. What finally saved his budding comics career was a union: the brand-new Syndicat des Dessinateurs. They urged their young member to widen his aims by looking for work among the daily papers. The result was a small stream of jobs from France Dimanche – a sensational publication modeled on English tabloids.

France Dimanche assigned Uderzo to draw "reports" that made small events and crimes more exciting. His territory became "juicy" affairs ("That meant anything spicy for which there were no photos"). To capture these, however, time was of the essence. "I was always 'behind'. I would finish one page, then begin another". Motorcycle couriers collected the work from his family's home but Uderzo found he loved the challenge. Soon, he was also part of France Soir's famous vertical strip Le Crime ne paie pas ("Crime Never Pays"). With the fees from this pair of jobs, he bought a drafting table and installed it in the family dining room.

The editors of France Dimanche, however, eschewed cartooning. What they wanted was realism. This had never been Uderzo's taste ("I was always into grotesques, caricature and big-nose comedy"). Yet within two months, the 22-year-old mastered it. He went from strips that were visibly maladroit into lines that were confident and dynamic. They were the polar opposite of Disney's genial rondeurs. But they would serve the tireless autodidact well.

His graphic about-face gave Uderzo more than nerve – it gave him versatility. It also built up his stamina, which was remarkable. He would start drawing before 5 am, stop for lunch and dinner, then work until midnight. Said Claire Bretécher, who met him in the 1970s, "The way those artists worked totally stunned my generation. Albert Uderzo finished a board a day".

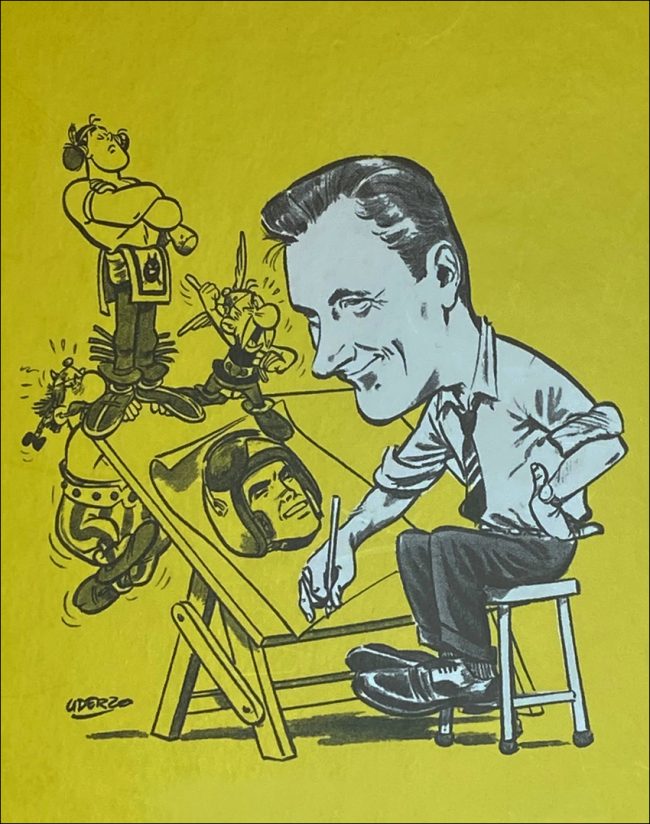

Not only did he produce in profusion; Uderzo learned how to switch his style in moments. At the time Bretécher met him, he was drawing two different strips every week. One, Tanguy et Laverdure, was the realistic tale of two airmen. The other was … Astérix. As Le Monde noted in their full-page homage, "Uderzo was and remains that rare artist who was every bit as comfortable drawing realistic comics as funny ones".

Alain Duchêne is a specialist on early Uderzo. With Philippe Cauvin, he published 2014's Uderzo L'Intégrale, 1953-1955. As Duchêne told French radio, "One of Uderzo's great idols was Franquin, who is of course a totally remarkable artist. But, although Franquin's style is singular, it's also something young artists try to copy. That's because as a style it's within their reach. Uderzo, on the other hand, may be the only BD artist who is never plagiarized. The style he developed is out of anyone's else's reach."

Style, however, is only a piece of the Astérix myth.

Viewed around the globe as quintessentially French, the Gallic saga is far from wholly domestic. Named after a typographical symbol – the asterisk – its star is, as critic Frederic Potet notes, "the purest product of immigration one could imagine". It began to germinate in 1951, the year "Al" Uderzo met René Goscinny.

Goscinny was then 25; Uderzo, 24. They shared the same favourite film, Walt Disney's Snow White, and had the same comic heroes, Laurel and Hardy. Les secrets des chef d'oeuvres de la BD ("Secrets of the Great Bandes Dessinées") gives a good summary of what their meeting brought together:

"Goscinny was a timid chap but very well-travelled. Born into family of Eastern European Jews, most of whom had died in the death camps, he grew up in Argentina. But in 1945, when he was just 19, he moved to New York – where his first works were created. These were children's books co-authored with Harvey Kurtzman, the eventual architect of Mad magazine. Kurtzman's humor, so ambitious, looney and surrealist, had a profound influence on Goscinny. It was also in New York that he met a Belgian called George Troisfontaines, who ran the syndication service World Press. Troisfontaines promised Goscinny work if he returned to Europe. "

By now, as it happened, World Press also employed Uderzo. Seduced by his journalistic strips about the Tour de France, they had hired him as an illustrator. But their Paris was still small and empty. To make it look "more professional", they imported both the artist and his drawing board. When, in 1951, René Goscinny re-joined his native France, he was assigned a seat beside Uderzo. It was, according to Albert, love at first sight. "Both of us wanted to turn comics upside down, make BD with a different sense of humor. We wanted to replace those custard pies with subtexts."

Goscinny had turned up with a detective strip, Dick Dicks. The staff at World Press rapidly agreed: all this offering proved was that Goscinny couldn't draw. The writer Jean-Michel Charlier, however, was struck by his wit. Charlier lobbied for Troisfontaines to hire him – with success. "At the time," said Uderzo, "René had some trouble getting his humor across. His jokes were too intellectual for something like Dick Dicks. I had the opposite problem – my graphic style was far too broad. Everyone we talked to turned down our early work".

This wasn't due entirely to their youthful failings. Although their medium badly needed to change, those in charge remained intransigent. "At that point," Albert write in his memoirs, "every editor had the same obsession. All they wanted was to find another Tintin. What René and I had to offer was different."

The pair's first efforts were old-school advice columns. Qui A Raison? ("Who's in the Right?") saw Goscinny masquerading as a Miss Manners, who dispensed traditional behaviour tips. Sa Majesté Mon Mari ("His Majesty My Husband") was the same thing, with harried-husband humour. Both were written by René and drawn by Albert. But they soon followed these with actual strips and new heroes such as Luc Junior, Bill Blanchart and Jehan Pistolet. Much about Jehan, a satire of pirate adventures, prefigured Astérix. It was a period fantasy set in the 18th-century. Yet the pair stuffed it with anachronisms, running gags, oddball visual allusions and puns. In what became the signature of Astérix, each of its happy dénouements ended with a feast.

Uderzo and Goscinny's first original character had failed. Oumpah Pah, devised in 1951, was an American Indian from the "Flatfoot" tribe. His adventures took place not in the Old West, but in the 1950s; their humor came from his misunderstanding of the era. At the time, World Press hoped to launch a US office – and they dispatched René to be its front man. When he set off to conquer Manhattan for them, Goscinny had six boards of Oumpah Pah in his bag.

Like its successors, Oumpah Pah held hints of the future. The critic Romain Brethes sees its hero as a "synthesis of the motors that power Astérix and Obélix – cunning for the one; force for the other ". Yet the projected series prompted no interest at all. Just like the idea of World's New York bureau, Oumpah Pah was summarily abandoned. Yet the two creators never forgot him and, in 1958, they resurrected the strip for Tintin. Bolstered by a new character, "Hubert de la Pâte Feuilleté" or "Hubert of the Puff Pastries", it enjoyed a huge success.

While Goscinny stumped Manhattan for Troisfontaines, Albert Uderzo had fallen in love. Twenty-five year-old Ada Milani was the secretary of singer Henri Varna. (Varna was also an impresario, who ran the Casino de Paris and a theatre). Ada's parents, too, were Italian immigrants. In 1953, the happy pair were married – and remained so for the rest of Uderzo's life.

Jean-Michel Charlier also found love. But the World Press family was less content. Charlier, who had training as a lawyer, told his fellow artists they ought to unionize. So the Paris group met up with their Belgian colleagues – and they hammered out twenty propositions. Charlier drew them up into an "Artists' Charter" meant to standardize their conditions and rights. Word, however, reached George Troisfontaines and he reacted by firing Goscinny. Troisfontaines had, they all knew, nothing against René. But the failure of World's New York office, plus the fact that Goscinny was "merely" a writer added up to make him an expendable employee. To Troisfontaines' surprise, however, his action failed to intimidate everyone. Charlier, Uderzo and their colleague Jean Hérbrand walked out.

These black sheep founded an agency of their own, which they called EdiPresse-EdiFrance. Despite being blacklisted by their former boss, they found work in advertising and from marginal firms that made chocolates and dairy products. Soon, too, Goscinny was writing for Tintin. Three years later, in 1959, the compatriots launched Pilote: a weekly that, like Mad, changed comics history. It was in Pilote's pages that René and Albert at last achieved their big ambition – they did turn the profession "upside-down".

These black sheep founded an agency of their own, which they called EdiPresse-EdiFrance. Despite being blacklisted by their former boss, they found work in advertising and from marginal firms that made chocolates and dairy products. Soon, too, Goscinny was writing for Tintin. Three years later, in 1959, the compatriots launched Pilote: a weekly that, like Mad, changed comics history. It was in Pilote's pages that René and Albert at last achieved their big ambition – they did turn the profession "upside-down".

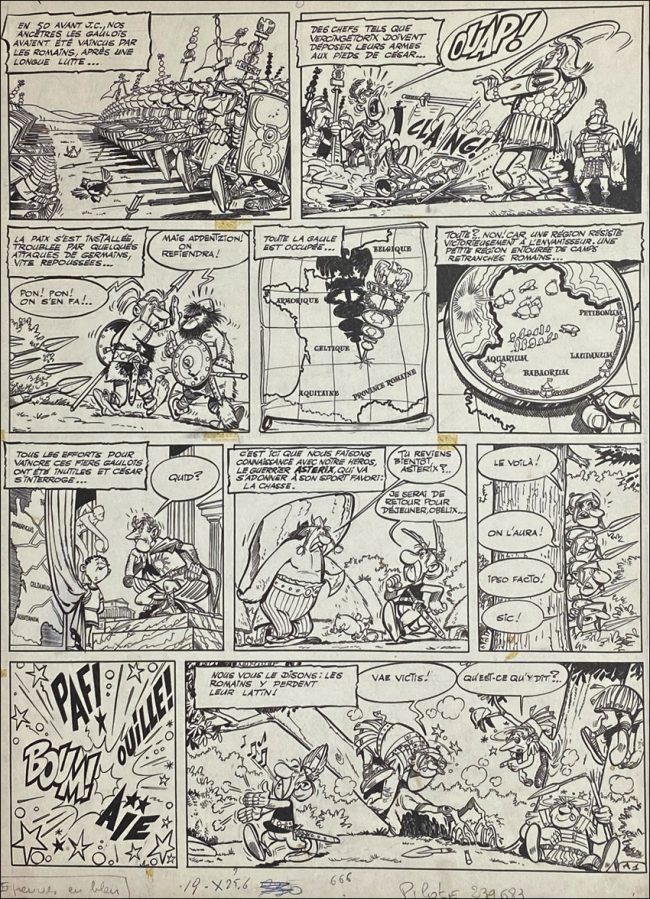

It had taken eight years of partnership. But, on October 29, 1959, Pilote's first issue introduced Astérix.

Pilote's runaway success was powered by the strip. Its first album version, 1961's Astérix le Gaulois ("Astérix the Gaul"), sold 6,000 copies. But its second, in 1962, had a run of 20,000 and its third, in 1963, more than 40,000. Six years later, in only two days, Astérix et les Normands ("Astérix and the Normans") sold over a million copies. The strip's meteoric ascendance seemed invincible – it led to toys, animations, radio and film. Then, in 1977, Goscinny died of a heart attack. After two years of reflection, Uderzo went on: scripting and writing the stories by himself, with a new imprint, his own, to publish them. Today, Astérix is read in 111 languages.

The fusion that created such longevity was unique. Goscinny and Uderzo, first generation Frenchmen, viewed both their common country and the world from different angles. Each confronted it through separate European sensibilities and tastes – but, also, through an education in American humor. What supercharged this recipe, of course, was personal chemistry – that of polar opposites who listened to each other. As René Goscinny's daughter Anne said yesterday, "Albert was the total opposite of my dad. Albert loved the countryside, he loved animals, he loved automobiles. My father detested the country, dogs weren't his thing at all and, for him, a car just got you from place to place. My dad thought civilization ended at the last streetlight".

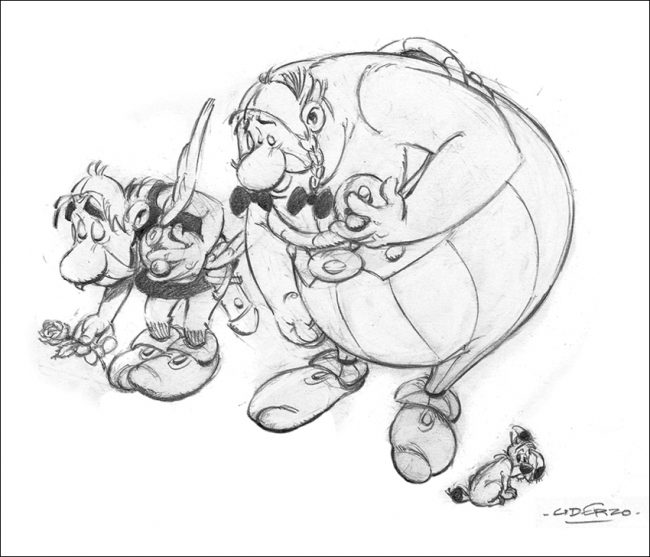

Neither creator ever grew complacent. Goscinny outlined every story in advance, carefully typing out precise, meticulous scripts. Uderzo followed them almost to the letter. But each was willing to give way to the other, as Albert noted when relating the birth of Astérix: "I had already sketched out this fairly big character… a clown, but within those lines used to show 'the Gaulois'. Then René suggested something totally different. What if he should be puny and unattractive? What if he were not so bright, just wily and cunning? The opposite of all those heroes we had been imposing on kids."

As the pair expanded the reach of their gags and inventions, their unique and tolerant complicity flowered. Astérix accrued cameos by film stars, allusions to popular culture – to paintings by Delacroix, Manet, Munch, Bruegel the Elder, Rembrandt and Géricault. All nods to the loftier arts were balanced by basic slapstick and accessible visual, as well as verbal, jokes. "Essentially," said Uderzo, "it was Laurel and Hardy in bande dessinée. We just wanted to find every option in the medium."

A good example of this was Uderzo's lettering. In some of his earliest strips as a solo artist, Albert got attention by changing this 'typeface' weekly. For Astérix, this became ongoing. The stories have characters who speak in hieroglyphs, in chiseled letters, via bullet lists or in fake 'lost languages'. They deliver curses composed of symbols – sometimes decoded at the base of the frame – or, in a chilly exchange, their speech bubbles drip icicles.

In September of 2011, Uderzo put down his pen. He was 84 and a life of endless labour had destroyed his hand and arm. "Astérix will live on after me," he said, "just as, when René died, I made up my mind he should continue." In 2013, with oversight from Uderzo, the torch was passed to Jean-Yves Ferri and Didier Conrad. The albums they produce just keep setting records. Last year's La fille de Vercingétorix, the 38th Astérix album, sold 1.57 million copies. In this nation of readers, it beat every other book – by far.

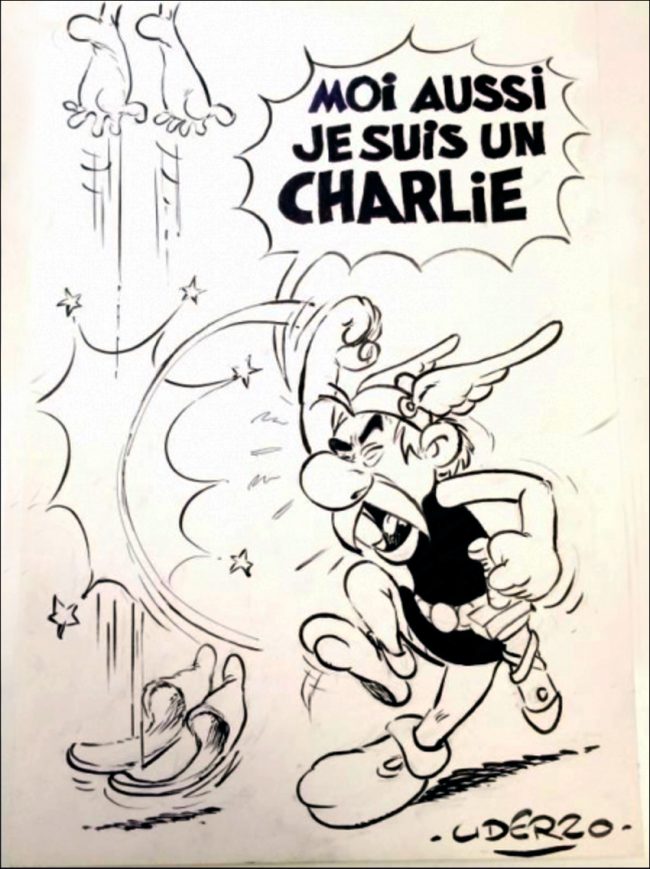

On January 7, 2015, all of France was floored by the murders at Charlie Hebdo. Albert Uderzo knew the slain artists and he was especially close to Cabu. They had met in the 60s, at Pilote. Two days after the terrible news broke, a drawing by Uderzo appeared in Le Figaro. It pictured Astérix punching an (unseen) assailant and shouting, "As for me, I'm Charlie too" ("Moi aussi, je suis Charlie"). "For five years," said Uderzo, "I hadn't touched a pen; I had to think about it all night long. But I offered that drawing from my heart; it marks my own belief in freedom of expression."

The national support, he said, "made me proud to be a cartoonist." If he could have, Uderzo said, he would have drawn for Charlie. Instead, he auctioned an Astérix original, adding a personal dedication for the buyer. It raised €150,000 for the victims' families.

Now the tributes are pouring forth for him. They have come from left and right, from every age group, from artists and fans and friends and celebrities. All of those expressing them have also spent almost two weeks in solitary confinement. As the French confront their share of a new pandemic, the idea of Gallic resistance strikes a nerve. Le Figaro, the paper that published Uderzo's last drawing, featured him in an editorial – on the paper's front page.

"Uderzo is gone…" wrote editor Bertrand de Saint-Vincent, "disappearing at a moment when our world resembles what he and Goscinny dreamt up… a citadel besieged. Encircled by invaders, their Gaulois have now been resisting for sixty years … For the moment, I suggest we ignore all those well-meaning recommendations to read – or, as the more diplomatic put it, 're-read' – Proust and Seneca. Instead, let us all reopen our Astérix albums. For it's all there, even a loathsome Roman charioteer called Coronavirus…They show us the best and worst, but let's retain the best. After all, it's now or never. Too bad if it doesn't correspond with all those virtues the wider world wants us to adopt. Let's remain unique and stubborn. Let's cultivate that spirit of resistance, based in friendship, that links Astérix and Obélix. Let's cultivate their profound love for their village, for their people and their history. That's the actual source of their supernatural energy. For let's not fool ourselves: the magic potion – that vaccine we're all awaiting – can cure nothing more than this evil of the moment. Theirs is the true spring of eternal renewal."

- With very special thanks to the excellent Uderzo L'Irreductible by Numa Sadoul (Hachette, 2018) as well as L'Intégrale Uderzo 1951-1951 by Alain Duchêne and Philippe Cauvin (Editions Hors Collection, 2014) and Uderzo Se Raconte by Albert Uderzo (Stock, 2008); René Goscinny, Au-dela du rire at the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire du Judaïsme (catalogue of the same name by Hazan, both 2018); Les secrets des chef d'oeuvres de la BD (Beaux-Arts Editions, 2017), Goscinny et moi by José-Louis Bocquet (Flammarion, 2007) and Goscinny by Pascal Ory (Perrin, 2007)

- The exposition Calvo, Master of Fables is due to run through May 31, 2020 at Angoulême's Musée de la Bande Dessinée. Attention, schools: For the show, Les Courts Tirages have made exclusive prints from Calvo's 1946 alphabet primer "Mr Loyal Presents: Beasts, Blarney and Capers". There is a poster for €50 and single letters can be ordered as numbered, limited-edition prints for €50. They have also produced fifty luxury gift boxes that hold thirty images. All are available via their web boutique. Gallimard has a beautiful, one-volume facsimile edition of Calvo's La Bête est morte