1. Why is the art of Wally Wood so hard to describe, so hard to get at? Why am I so interested in the care Wood put into his art, while the similarly painstaking craftsmanship of a Joe Kubert or Will Eisner leaves me cold?

2.

People are obsessed with this panel. I love looking at it, and who doesn't? But thinking of Wood as a 'sci-fi' artist leads one astray. I don't look to Wood to have my mind opened to new concepts of reality or what is possible within the cosmos. Wood's art is about the human world, and very specifically his own world. It's revealing that people care about this panel and not the six pages of so-called sci-fi it serves as a conclusion. It might be the only point at which we confront Wood's art for what it really is: an expression of the complicated reality of Wood himself, an artist of enormous talent in an industry that was indifferent to all but the most superficial aspects of his expression. The idea of Wood as a 'sci-fi' artist is one of many side roads diverting us from the richer truth of what he was up to.

3.

Here's a sad story, which can be found in the excellent The Life and Legend of Wallace Wood, Vol. 1, edited by Bhob Stewart and J. Michael Catron. It comes to us via an exchange between Wood and Mark Evanier:

Wood: I enjoyed working with Stan [Lee] on Daredevil but for one thing. I had to make up the whole story. He was being paid for writing, and I was being paid for drawing, but he didn't have any ideas. I'd go in for a plotting session, and we'd just stare at each other until I came up with a storyline. I felt like I was writing the book but not being paid for writing.

Evanier: You did write one issue, as I recall--

Wood: One yes [Daredevil #10]. I persuaded him to let me write one by myself since I was doing 99% of the writing already. I wrote it, handed it in, and he said it was hopeless. He said he'd have to rewrite it all and write the next issue himself. Well, I said I couldn't contribute to the storyline unless I got paid something for writing, and Stan said he'd look into it, but after that he only had inking for me. Bob Powell was suddenly pencilling Daredevil.[Later on in the interview] ... I saw [Daredevil #10] when it came out, and Stan had changed five words---less than an editor usually changes. I think that was the last straw.

Quite a bit of smoke and mirrors to get out of paying someone for writing. It gets at a key point about Wood: all this relentless professionalism, all this ambition to be one of the best artists in his field and ... for what? Why? The desire to do something well in comics, and the much rarer execution of that desire, is treated with deeply abstract (or, more accurately, opportunistic) reactions. 'Thank you for all your hard work. I will now wage a campaign of confusion so that I don't have to pay you what you're owed.'

Lee's spectacularly immaculate record of mistreating his artists is no great revelation, of course, but comes alive when we place it next to this statement about Wood from Harvey Kurtzman (also pulled from The Life and Legend of Wallace Wood):

Wally Wood was a workhorse, and I feel that Wally devoted himself so intensely to his work that he burned himself out. He overworked his body. That's my own observation. Wally had a tension in him, an intensity that he locked away in an internal steam boiler, and I always had the feeling that Wally was capable of erupting---which he apparently did occasionally----but he had that quality of frustration and tension and I think it ate away his insides and the work really used him up. I think he delivered some of the finest work that was ever drawn, and I think it's to his credit that he put so much intensity into his work at great sacrifice to himself.

Most people first see Wood's work as a child, and it leaves a lasting impression. It certainly did on me. To a 10-year-old, it seems like magic. Later, we hopefully comprehend that a lifetime of effort and dedication was the true magician. Of course, when people are going out of their way to not pay you, your effort and dedication might just have to be tripled, and that might affect your physical and mental health. We talk a lot in comics about intellectual property, about how certain artists didn't benefit from the money their billion-dollar characters generated. But what about the abuse of the faith (in Wood's case, deep faith) these artists placed in making the art itself? What does that look like in reality?

4.

When Wood pared down his style, a horrible emptiness to the world he rendered begins to emerge. That's not a criticism, as I prefer Wood's simplified style to his more famous EC detail-upon-detail mode. Hovering around every line is a crushing lack of warmth, a cynical world without a single utterance of actual cynicism. Wood communicates a story through drawing better than anyone, so you are guided through a world void of feeling with expert precision. You stop and confront it head on. Here it is, looking right at you:

I don't feel unease from what this figure (The War-Lord) is saying, but I feel a real horror in how Wood chose to draw him. It's a hugely depressing image in its coldness. And yet Wood's T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents stories are as divorced from a world where 'depression' or 'sadness' exist as anything put to page. Unlike a social critic making a point about lack of passion, we are left with the thing itself. The above splash page of Noman really sums it up: a perfectly rendered figure, 'invisible' but more accurately described as ghost-like, standing stiffly in a perfectly ordered, lifeless world. The answer to my question as to why Wood put so much care into his work in the face of such indifference is almost answered in the drawing: 'I've erased my feelings about all of that.'

Twelve years prior, Wood gave us images like this one. Kurtzman's assessment of Wood mentions 'intensity... capable of erupting,' which I take to mean anger. That quality is evident even in a 'joyful' image like this one, with its ruthless determination to render meticulously something so ridiculous. But the contrast of feeling between this and Wood's work for Tower, which paid badly, is a story in and of itself. A decade and a half in the comics industry has left a mark on the artist. Yes, Wood probably pared down his style mainly to save time, to be able to generate more work and thus support himself. But the absence of feeling smeared all over the simplified panels is something beyond mere simplification.

Is the story of Wally Wood's art 'I am a science fiction artist. My name is Wood' or a pictorial statement of self-negation from someone whose work was never fully appreciated? That drawing of Noman screams, 'This is where I'm at now.'

5.

Here's one more sad story from The Life and Legend of Wallace Wood related by Wood's peer and art-partner Harry Harrison, describing what it was like to work for Fox Comics in 1949:

The art director would say, 'Well, yeah, this is great stuff but we don't pay very much. Know what I mean? I think the rate at Fox was $23 per page for ten-page stories. And while he was talking, he'd slip you a note saying something to the effect that they also expected kickbacks of $5 a page. This made a big difference to us in the rates, of course. But all these guys took kickbacks, and if you didn't go along with it, you wouldn't get any work...We would slide in this ten-page pile of crap with a real good splash page for the first page on top. He would look at only the first page and count the other nine, flipping through them fast. Nobody really cared about the quality. Nobody looked at these books, no one read the things very carefully. So he'd count the pages. We'd give him the $50 or whatever it came to----$5 a page in kickbacks---and then we'd get our check in the mail from Fox, not necessarily in a week or two but in a month or so, sometimes slower than that. The money owed would add up...

Wally Wood was 22 when he was working for Fox, and this is quite an introduction to his chosen profession. So many artists of this era left comics for advertising or illustration, and of course why wouldn't they? Treatment like this was standard. Wood, on the other hand stayed with comics forever, as did practices like the one in place at Fox. Lee, sixteen years later, was essentially doing a crueler version of the same thing, depriving Wood of money for his writing, and syphoning it into a credit for himself.

Wood made perfect drawings throughout his life and placed them into this sea of maltreatment. His self-publishing, with Witzend, might have been the only space where his work was not preyed upon in some fashion, meaning the only business partner Wood could be safe with was himself. Only Wood fully appreciated and respected what Wood was up to, a hard thing to reconcile when his vast artistic achievement is immediately apparent, even at a side glance.

6.

But, again, what is this vast achievement, exactly?

When I look at a Wood story from Shock SuspenStories, it reads as a document of a singular project that I can't quite explain to myself. The writing in Shock SuspenStories is, at its absolute best, silly. But the art Wood put into those stories cannot be dismissed as 'first-class illustration of pap.' Instead, it expresses something as it grafts itself onto a template of cliches that do not. But why and how? Internally we tend to solve the question in our heads with 'wow, look at the detail!' But I don't think this answers much if we are truly engaged in taking the time to examine our honest reactions to Wood.

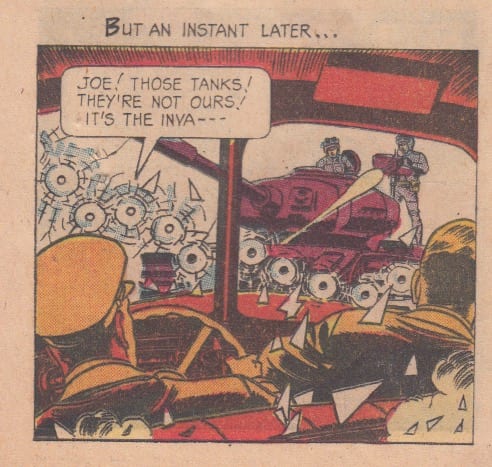

I'm uncomfortable with my usual "improvised" conclusion, that artists like Kubert and Eisner were more adept at keeping themselves financially secure than Wood was, and that because of this their work feels more 'safe' to me. Instead, I think a closer stab at the truth centers on the notion that Wood's heart and mind are richer than Eisner and Kubert. Even when confronted with a particularly mindless sequence like this one below from Total War #2, I feel the presence of an actual human, fully involved:

There is emotion here too, though it is extremely clipped. I don't mean emotion in that Wood 'feels' for the murdered civilian in panel 3. As with the lack of voiced dissent in T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents, that's not what Wood is about. But there is feeling from Wood himself for what he is trying to accomplish, for pulling it all off. What emerges to me about Wood's art in this period is an angry defiance. This sequence almost says, 'You can debase what I do, but I'll continue to do it better than the rest, even as I take away the bells and whistles that people superficially latch onto. I will take a pride in it, and it will continue to be done well, even as it is done less and less to please you.'

The violence in Total War and T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents isn't bloody, but it is blunt. You don't empathize with the civilians, but you recognize that brutality has been done. It's not the villains that are doing the destruction here, but the artist, and it's directed inward. That his focus and his allegiance to his craft remains crystal clear as this battle is waged----yes, here we come to part of what I think makes Wood so important and why I always want to read one of his stories. He is there, in every one of them, and often there with pain, though he never indulges it.

7.

Wood once said: 'I'm an artist, I do it for a living.' The larger context for the quote is Wood stating that he doesn't spend too much time worrying about whether he is defined as a high or low artist. 'They sell those fine art paintings, don't they?' He is an artist working for a living like any other. But the quote opens itself up widely. Wood accepted the limitations and degradation of his chosen field in that he remained loyal to comics his entire life as an artist. But coupled alongside that acceptance, we witness a deep rejection in the undertone of his stories. Wood's intelligence could not remain unaware to the paradox of his situation, and the art he dedicated his life to producing has that understanding imbedded into every line.