Al Jaffee, at 99, is among our last living links to the beginning of comic books. Young Al bought the first issue of Famous Funniesin 1934 when he was 14. His life spans the whole history of comic books, first as an engaged and enthusiastic fan, and then, as we all know, a professional cartoonist.

Jaffee was born in Savannah, Georgia, but lived in Lithuania for a total of five years between the ages of 6 and 12 when his mother took him and his siblings back to her home country (twice), before settling permanently in the U.S. He grew up reading and adoring comics and displayed a knack for drawing as well. He quickly set himself the goal of becoming a comic book artist and achieved that goal in 1942, working first for Will Eisner’s shop, then for Marvel (called Timely in those days), where he worked under a 22-year-old Stan Lee. Jaffe became what could best be described as a journeyman comic book artist, working on staff at Timely for a while and cranking out whatever features were called for, eventually writing his own stories, but always more attracted to humor than other genres.

He finally came into his own when he met Harvey Kurtzman and started contributing to the magazine incarnation of Mad with issue #25, cover-dated September 1955. When Kurtzman had a falling-out with Mad publisher Bill Gaines three issues later, Kurtzman left to edit the humor magazine Trump (a title now ridiculous but no longer humorous) for Hugh Hefner, and Jaffee followed. Trump lasted two issues, and Jaffee, with artistic compatriots Kurtzman, Arnold Roth, Will Elder, Jack Davis, and Harry Chester, embarked upon their next adventure by self-publishing their own humor magazine, Humbug. Humbug lasted eleven issues and featured some of the most passionate creative work of those gentlemen’s careers. Nonetheless, Humbug, too, went bust. It was immediately back to Mad for Jaffee, where he found a home for the rest of his career and has regularly and happily contributed to it from 1958 until about a week ago.

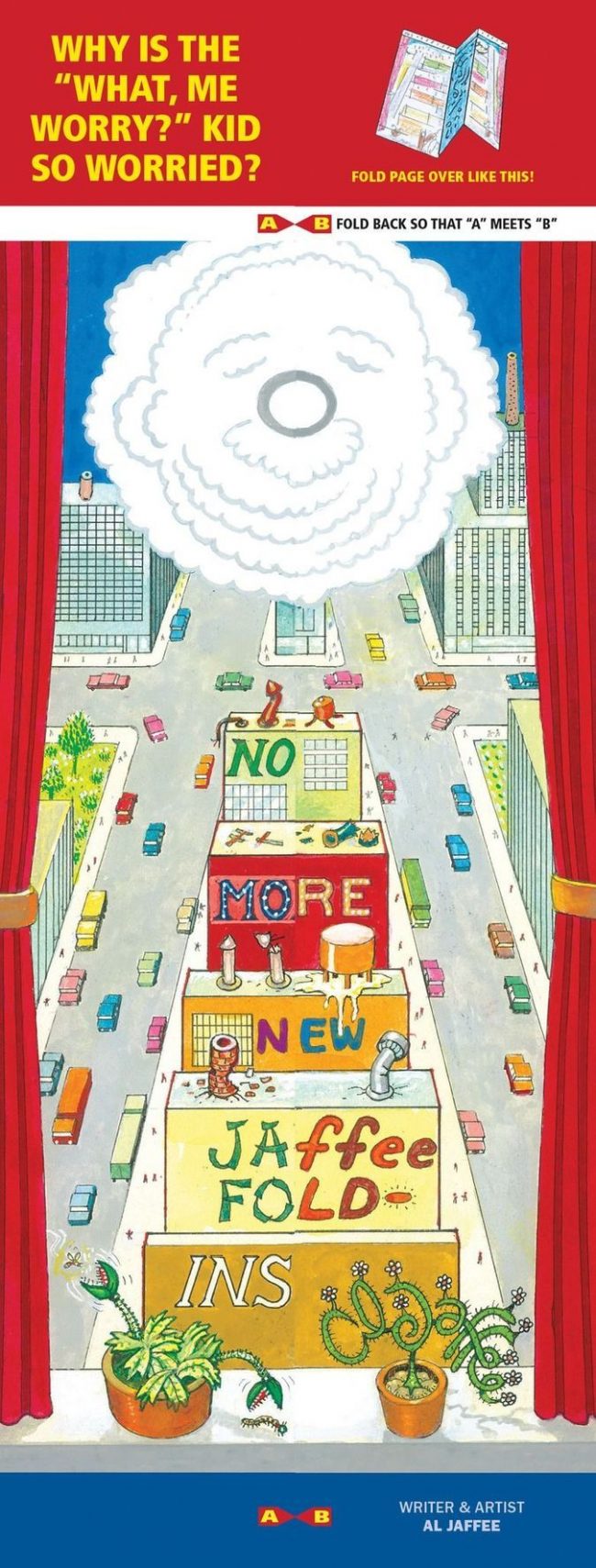

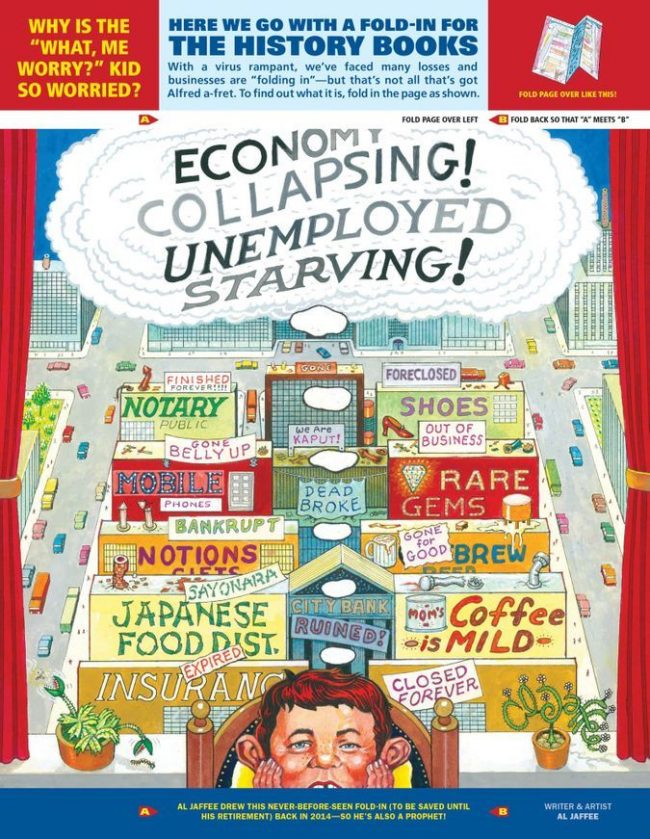

Jaffee is undoubtedly most famous for his vaunted Fold-In feature (his response to Playboy’sfoldouts) that has run continually in Mad since he created it in 1964 (he missed only one issue), but he has also contributed a wide variety of other features to the magazine, including Snappy Answers to Stupid Questions and scripts for Mad’smovie parodies. The most recent issue of Mad is dedicated to Jaffee and includes tributes and reprints of some of his greatest hits. With Mad having gone to reprints, Jaffee has, in some sense, outlived the magazine.

I met Al in 2007 when I was editing Fantagraphics’s two-volume set collecting the eleven-issue run of the original Humbug magazine. Al was the only Humbug artist/co-owner whom I didn’t know, and our mutual pal Arnold Roth introduced me to him. I subsequently worked closely with Al, Arnold, Will Elder, and Jack Davis to recover the vanished original art from Humbug — a 60-year-old mystery that was finally solved, but not without some psychological, legal, and financial damage to all concerned (another story for another day).

I’ve made it a point to see Al whenever I go to New York; our good friends, Arnold and Caroline Roth would complete the dinner party. And, of course, Al’s effervescent and witty wife, Joyce, was also part of our get-togethers (I have not seen Al since she passed away recently.).

With Al’s recent retirement, much covered throughout the media, I thought now would be an opportune time to give him the chance to speak about his life and career.

— Gary Groth,

June 29, 2020

GARY GROTH: Al, you’re able to walk, right?

AL JAFFEE: Oh yes, I can walk. I don’t go out much. I have an aide, a caretaker, and if it’s nice out we go out, walk around the block. But I don’t get out too much.

That’s great if you can walk around the block.

I try to do that.

I hope when I get to New York next time we can walk around the block to a restaurant.

That’d be lovely, Gary. I would look forward to that.

I appreciate this telephone call, because it gets lonely when you’re out of the swim. You don’t meet your fellow cartoonists. I just sit home and take naps, that’s it. On my next birthday I’ll be 100, so I’m not complaining. I may be housebound to some degree but I still can get around.

I hope on your next trip to New York we can get together, because I’ve always enjoyed your company. Let’s hope that comes about.

Absolutely.

Well now, everyone knows you retired. It worried me, Al, because you’re only 99. And I’m thinking, “Why is he retiring at 99?” I could understand if you retired at 110, but 99 seems a little young.

I’m a little embarrassed about that. [Laughter]

Not working long enough and hard enough.

There’s another century around the corner.

I realized that you’ve lived through the entire history of comics.

Yes, I’ve been there a lot, yeah.

You bought Famous Funnies in 1934—

That’s right.

—so you were fully aware of comic books from the very beginning.

Oh, absolutely. My brother Harry and I just gobbled them up. I loved the early comic books, because they had a lot of the old heroes in it. They had Mutt and Jeff and a variety of [characters from] the newspapers. The Hearst syndicate. And they were like old friends. It was great.

And it must have been exciting to see them in color and in a different format than the newspapers.

Oh yeah. My mother took me and my brothers back for a short trip to the town she was born in in Lithuania. Well, the short trip took four years, and all that while I wrote desperate letters to my father in New York and told him how much my brother Harry and I missed our comics. So he started sending them to us. He would send a roll of dailies and Sundays, so we kept up with it. It was a great time because there were all kinds of experimental stuff. I loved Rube Goldberg’s work and his inventions and all of that. But all of them were good. It was a new art form. And especially when you’re living in a foreign country, you want to keep up with what’s going on in America. The Sunday comics did a fantastic job for me and my brothers. So it’s been a lifelong love affair with the comics.

How old would you have been when you got these care packages?

I was probably around five or six. I was just learning to read. And I managed to keep up with English, because the comics were so enthralling. Of course we had to ask our mother for interpretations of certain phrases which were common at that time. But we kept up with it and it was wonderful. Little Orphan Annie and Boob McNutt. Oh, we looked forward to that so much, it was almost like we were looking forward to our trip back to America.

And that’s before we were all inundated with media.

Oh yes. King Features was a primary source of cartooning but there was a separate syndicate. It’s hard for me to remember because we’re talking about 60, 70 years ago. There was King Features and the New York Daily News had a syndicate.

Would that be Pulitzer?

They syndicated Winnie Winkle, Little Orphan Annie, a lot of stuff that appeared mainly in New York.

Well, Pulitzer would’ve been the New York Journal-American.

It did appear in the Journal-American. And of course the New York Daily News became one of the most successful tabloids. And they had a big Sunday comics insert, but they also had daily comic strips. It was a fascinating time if you loved cartoons, because they were just beginning to break out. I loved them. I couldn’t wait to get my hands on them.

That was an exciting period because newspaper strips were still new, and new enough not to fall into formula.

Right. And also they didn’t need to compete with anyone else except each other. I mean, Hearst would compete with Joseph Medill Patterson. The big shot Citizen Kanes, they competed with each other not with the cartoonists. But the cartoonists benefitted because if Hearst or Patterson saw a comic he fell in love with he’d make an offer that a guy couldn’t refuse. So it was a wild time. Of course, I was a little kid then, so I didn’t know from the business end. I was just in love with the art and the writing. Oh, I loved it.

Were you drawing at that early an age?

Oh yes. In fact, every letter that we wrote to my father who was back in the US had drawings that my brother Harry and I inserted. My brother Harry was infatuated with the Japanese-Russian War, and he made a lot of wonderful drawings of what was going on there in his imagination. So it kept us busy. Kept us out of trouble.

And you couldn’t sit around and watch TV all day.

No, no, we didn’t do anything like that. At that time, you couldn’t buy things, you had to make ’em. There was nowhere to buy a fishing pole. So my brother Harry and I went to the woods and cut down two or three saplings and made fishing poles. And they were wonderful. Later on, of course, things started to open up even in Lithuania, but I have good memories. We were in a town that was on the top of a plateau and surrounded by a lake. And so if you went downhill on any street, you’d go into the lake. In the wintertime it was all snowbound, so we used to get on our sleds and ride down the hill and wind up a half a mile by the lake. Oh it was great.

Sounds idyllic.

It was. Except of course it was during the Great Depression and people all over the world were suffering from being unemployed and not having any spending money. I had some because my father sent it from New York.

What did your father do during the Depression?

He was a postal worker. Actually, he ran a department store in Savannah, Georgia, but he was fired because he was too involved with his family. He spent a lot of time writing and going to the post office to send us things and all that — so they fired him. So he got a job in the post office because he was a veteran of World War I. So that’s where he spent the rest of his life.

He was a very well-read, intelligent man who only graduated from night school in the US, but he was a pretty good guy. And he taught us to draw. He’d sit down on a Saturday or Sunday with my brother and me and he’d copy all the cartoons. And he was good at it.

Would you call him a weekend artist?

Yes, he was a weekend artist. And I thought it was magic. Oh god, it blew me away. And I just kept on trying to be as good as he was.

Well, you probably succeeded.

Well, maybe. My brother Harry succeeded also, because he loved the airplanes so he did paintings of airplanes. And they were selling so well in the stores that he took them to, including Macy’s, that a distributor came by and made him a terrific deal if he would let the distributor distribute them, and they were all over the country.

[Looking them up on the internet] Al, I’m looking at pictures of your brother’s airplane paintings.

Aren’t they great?

Yeah they are, they’re accomplished.

Yeah they are, they’re accomplished.

You should’ve seen him do them. In a half hour, we had one done. I and my brother Bernard, we helped him. He’d make a drawing of an airplane, and he got us to trace it onto sky blue paper. And once the tracing was there, he took over with paint. And it was just amazing to see him make a line that was just a hairline that ran the length of the plane. It might be an antenna or something like that. But there wouldn’t be the tiniest of ripples in it, it was just perfect. Very precise. He was in love with airplanes. He would go to the airport and sit there and sketch them all day long before he came back to paint them. And he hired me and my brother Bernard and we did his tracing because he was much more valuable as the painter.

When would this have been?

This was in the Bronx, New York. About 1936, ’38. We were teenagers.

Did your brother go on to make a living as an artist?

Yes, he did. But he had a breakdown and had to go stay in a hospital.

A nervous breakdown?

Yes, a nervous breakdown. He was a very sensitive kid. And he just couldn’t take the grind, because the only way he loved doing artwork was for himself, the things he loved. He didn’t want to have assignments. So he did work for various agencies. Everybody wanted him, he was a fantastic colorist.

Did he do advertising work?

He did advertising. In fact, he worked at an advertising agency doing comps an all kinds of things like that.

It seems like you were much more adaptable in that you would take assignments.

He was not a cartoonist. He did not see the humor in drawing. If you said, “Paint me a Cadillac or a Ford,” he could do that in an hour and it would be a perfect rendition of a model Ford. So he had a lot of assignments, but he also had a mental breakdown and he had to go to a hospital. You can’t put too much into your job, it’ll eat you up. [Laughs]

Is that how you felt throughout your career?

No, I was a hooker. I would do anything. And I enjoyed it.

Do you feel like you put a lot of yourself in your work or did you have a boundary there?

I put whatever a client asked for into it. And there were times when I failed because when I got involved with products the agency that handled the products went over it with a fine-toothed comb. I had stuff rejected, because humor was really my strong suit and straight illustration was for people like my brother. So I’m glad I failed at it.

It’s interesting that the two of you went in such different directions.

Well, when you had no model to go by, I felt very lucky when I got a call for somebody who said, “I need an artist for such and such.” Even it was a struggle to earn 50 bucks, I felt successful.

You had no problem being a hooker.

No, I didn’t. [Groth laughs]

Now, I’m getting a little ahead of myself but was there a point in your career where you felt you stopped being a hooker and did something that had greater meaning to you personally.

Well, yes.

Would that have been with Mad?

Originally it was with Harvey Kurtzman and Playboy where Hefner gave us a very big break and we came out with a magazine called Trump, which had the production quality of Playboy. So I could do paintings and all kinds of stuff. It took forever of course, and we made no money, but we loved it. And then Hefner gave us the bad news that it wasn’t making any money so he was going to have to kill it. And he were hired by a printing company in Connecticut to continue doing a magazine like it, called Humbug. [The title] was Arnold Roth’s doing, he loved the English… he was an anglophile.

Al, was Trump the first time you feel like you expressed yourself?

Oh yes, because you could use any medium. I did black-and-white paintings, I did color paintings, you could pretty much go as far out as you felt. I don’t know where it would’ve all led, because it takes a lot of time to do a full page in full color, but it’s a crazy history.

Well, I think Trump came out in 1957. Prior to that, were you working for Stan Lee?

I started my cartoon career with Stan Lee more or less. My first job was with Will Eisner, and I really loved working with Will because he was such a bright man. I learned a lot in his studio. He had a lot of other cartoonists who went on to become very well known, great guys. But he couldn’t pay me more than $10 a week. So between lunch and the subway I had nothing left after three days. So I ran into a friend, Alex Kotzky, and he was working with a cartoonist. They were doing stuff for Stan Lee, and my friend Alex Kotzky said, “Well if you want freelance work why don’t you go see Stan Lee?” So I did. And in my first meeting with Stan, he said, “Create a character for me.” A comic book character. So I went through my mind and thought of all the animal characters that had already been done — Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse, and so on. And I realized that the only one that hadn’t been done was a seal. So I proposed doing “Silly Seal.” And Stan said, “Yeah, give him a sidekick. Maybe a little pig.” And we decided on Ziggy Pig. So Silly Seal and Ziggy Pig ran for a long time. I went into the service and I couldn’t do it, so Stan had other artists and writers do it, and it became very successful. It’s still running!

It is?

It’s being done in California.

Huh. So Stan Lee was a year younger than you. You were both pretty young.

Yes, we were in our late teens.

Was Stan Lee an astute editor in your view?

Yes. He made light of everything. I think he was like Hollywood’s version of a lucky kid who was appointed editor of his favorite comic books, and he was having such a fun time with it. And he was hiring the people he liked.

Did you work for Stan before you entered the service?

Yes, I did a couple of stories for him. I did Squat Car Squad, I dunno if you ever saw it, it was two bumbling policemen. I had a lot of fun with that. Poking a power figure in the eye is always a lot of fun. [Laughs]

What kind of a person was Will Eisner?

Eisner was very bright. And he was very nice to us. He would come and look at us once every day. There were about four or five of us working in his studio, really good people. I learned a lot from them.

Was Alex Kotzky there?

I brought Alex Kotzky there. When I left Eisner, I looked up Alex Kotzky — because we went to the same high school together — and I said, “Alex, how would you like me to be a salesman for my stuff and your stuff? You handle all the adventurous stuff and I handle all the cartoon stuff. And he said, “Great,” and he gave me some samples. Of course, the first guy I went to was Eisner, because I knew him, I worked there. Eisner took one look at Kotzky and he said, “Can you send him up here?” And he hired him on the spot!

Kotzky was very good.

Oh, he was very good. Of course, what I didn’t realize was that Eisner was getting a comic strip in the newspaper and he couldn’t handle all the work he had, so he took Kotzky on and before you knew it, Kotzky was doing his strip. I couldn’t do it at all because I was trying to make a living as a freelance cartoonist which is pretty tough. But there were some big talents in the business and Kotzky was one of them.

So you were working at Eisner’s studio when he was doing The Spirit.

I was just filling in.

What was the atmosphere like there? Did you all get together after your work?

We did on occasion go out to lunch together or have lunch brought in and all of us share stories, but I wasn’t there long enough. I mean, I was at Eisner’s place for three or four months. So I didn’t become part of it.

When did you go into the service?

Shortly after I left Eisner. And in fact, I saw Eisner at the Pentagon where I was assigned. I ran up to him, he was an officer and I was a sergeant and we took me to lunch. It was very pleasant.

When you worked for Eisner and then when you got out of the service and worked for Stan Lee, were all of your colleagues obsessed with comics? Did you talk a lot about comics and the artists in the field.

I think in the back of the minds of everybody who could draw straight figures — you know, Captain America, Spider-Man, and Superman and all that — they all yearned to go into syndication. Because you could work wherever you wanted. You could move down to Florida and send your stuff in by express mail or whatever. And everyone dreamt of that. But there were very few spots in newspapers so reality set in and we realized that we’d either make a living in comic books or we would spend our entire life going to syndicates and getting rejected. I did some syndicate features myself, one of which was sold — Tall Tales [1957-1963]. But I did a lot of others and I couldn’t get them off the ground. Satirical, not realistic ones. I think I had some good ideas I could’ve developed, but I was very happy to have Stan Lee say to me, “Create a couple of animal characters and you can put them in your own comic book.” And that was Ziggy Pig and Silly Seal.

And that was their own comic?

That was in their own comic, and I continued doing them after I volunteered to go into the Air Force. I’d be sitting in my barracks doing six pages of Silly Seal and Ziggy Pig because the extra money was so valuable when you’re in the service. A private doesn’t get much pay. So I would take all my buddies out for a bite to eat and we’d have a great time.

Were you a private or a sergeant?

I went in as a private and I came out as a tech sergeant.

Did you like your experience in the service?

Yes, I liked it. I liked the people that I dealt with, and I thought that we were treated fairly. There were occasions when we were asked to do something that was humanly impossible, and that kind of irritated all of us — to go on a five-mile march before lunch, it really pissed us off. [Laughter]

You didn’t go overseas, did you?

No, I did not.

Were you very political back then?

I was, but there was no outlet for me. I would have loved to have been a political cartoonist but could not do it. All the famous ones that I read had it tied up.

But you would’ve been interested in doing that?

I would’ve been happy being a syndicated political cartoonist, sure. You get to say what your paper wants and what your readers want and do it in a funny way or a clever way. It’s still very appealing. But it’s very tough. There were good guys around at that time: Herblock and lots of others. It was a very high class job.

Bill Mauldin.

Yeah. I’ve been very lucky in this business, because I got to work on things that I enjoyed doing.

It sounds like Trump was the first time that you could truly do what you wanted to do yourself.

It sounds like Trump was the first time that you could truly do what you wanted to do yourself.

That’s only partly true because Harvey Kurtzman was a very tough editor. I wouldn’t criticize him for any reason whatsoever, I loved him, but he had very definite ideas about what satire should be like and how much space should be given to certain kinds of satires. He weighed everything. I’d come in with what I thought would be six pages of stuff and he’d reduce it to one page! [Laughter] And we got paid by the page. But all in all, I have no complaints. I loved working for Eisner, I loved working with Harvey, and Harry Wilco was a wonderful editor at the Tribune syndicate. I’ve been very fortunate. Maybe I’ve been fortunate because I could understand them and I could give them what they wanted. That might be the key.

I don’t think you were ever a prima donna.

No, I never was a prima donna. I asked them very frankly, I said, “Do you want these characters to look realistic or do you want to be funny like Mutt and Jeff?” And from the answer I got a mix of ideas.

Do you think you always struck a balance between what you wanted to do and what someone else wanted you to do?

I think I did. Not always successfully. I did samples for a number of people and they didn’t take it on, they rejected it because they wanted humor in it but they also wanted it to appeal to kids who were looking for straight stuff. Sometimes that mix is impossible. But there have been people who’ve pulled it off very well. And I’ve tried. And I wrote stories with plots like people who are planning to steal the Brooklyn Bridge. But everyone has a notion of what’s funny and what’s beyond realistic.

What do you think has been the work you’ve done that is the purest Jaffee? That’s the most you.

I’m not sure about that, Gary. I really try to get into the mind of the person that’s buying it. Because every one of them has a different notion. They’ll fall in love with a character in one comic strip, and then they’ll try to hire somebody to try to do a competitive character of the same sort. And it just comes off as a copy. I’ve tried it, and I’ve failed. But I was always able to get something.

I have a hypothetical question. If I were to say, “Al, I’m going to give you a boat full of money and you can just do whatever you want. Whatever Al Jaffee wants to do. I’m giving you no direction.”

I couldn’t do that without a lot of thought. [pause] I’d have to take my age into account.

Well, it’s hypothetical, so hypothetically you could be 50. [Jaffee laughs]

Yeah, OK.

You grew up in the comics business when comics were less about personal expression—

Oh, comics were in their heyday when I was growing up. I mean, you could do almost anything and sell it to a comic publisher.

Well, you still had to work within certain commercial parameters.

What every cartoonist really wanted was the security of a syndicated feature. So we created a lot of syndicated features and the syndicates turned them down, and then we went to the comic book publishers. And they bought them as fillers, they bought longer stories than that. But everything was up for grabs. You had to be creative.

Did you try to break into newspaper syndication in the ’40s?

I had a friend who was the syndicate editor at the Herald Tribune, and he’s the one who bought Tall Tales. And he kept after me. He said, “Why don’t you create a comic strip for me?” And I did create a bunch of them but I wasn’t satisfied with them. I didn’t think I could maintain it. It’s very funny in a week’s samples, but then how do you go on for a year?

Or 20 years.

Yeah!

Do you have these strips that you did, these samples?

I wonder… I’ve moved so many times and I’ve left stuff in my houses. I can check with my niece and she might have saved some of them, it’s possible.

That would be important for your legacy to preserve that.

Oh, yes. But when my first wife left me I was so desolate that I just threw out all the stuff in my studio, threw it out in my yard, and people picked it up as they walked down the street.

Oh my god!

I had a lot of good stuff. Not only mine, but I had originals by other people. But I lost my mind there, and I can’t explain it.

What year would that have been, Al?

That was 1970 or maybe 1969, somewhere around there.

And you were so distraught you threw out a lot of your work?

I left everything. I left it all. And I had a tough time looking for work because I didn’t even have samples of my own stuff.

That sounds like a very hard period.

I started a new life, and I don’t regret it. We all had new lives. My ex-wife had a new life, and I did.

So that was painful.

It was very painful. My wife who left me was someone I met in the Pentagon. She was a sergeant, and she was probably the most beautiful WAC in the business. And we started going out together, and one day I proposed to her and she accepted. I was madly in love with this woman. But she met somebody else who promised to take her back to California, and she fell for it.

And so you had to pick yourself up.

Another soap opera. [Laughs]

But you had to pick yourself up and reestablish your life. How did you go about doing that? How did you go about reestablishing yourself personally and professionally?

Well, it took a long time. The first thing I did was find an apartment in New York. I held onto my house and commuted to this apartment and worked there. And finally I decided I didn’t need the house any more. I just started selling things and giving things away and sold the house. I stayed in New York and started a new life.

I have two children and a lot of grandchildren and great grandchildren. And things have worked out OK.