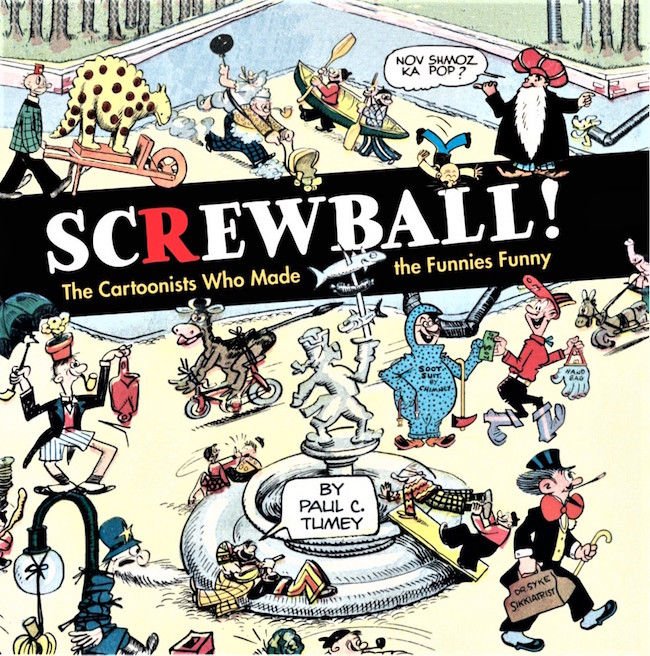

Screwball follows an isolated strain of comics history as opposed to those other books that tell the whole lot decade by decade or by lining up a canon of masters. Which is not say it isn’t linear: from Fred Opper to Boody Rogers, editor Paul Tumey locates fifteen cartoonists in a singular furrow, giving each a solid apportionment of twenty pages, some besides, some beneath. A species of humor is Tumey’s theme, the zany zest that made the comics an event that had not happened before: the nutty, the loony, the madcap and the high nonsense. “Nov schmoz ka pop” as Ahern’s little hitch-hiker said, and it loses none of its power and profundity when I say it here.

The nice result of such a scheme is that we can get to see a big sneeze of work by a relatively obscure cartoonist such as the marvelous Walter Bradford, an early denizen of the funnies who is usually overlooked by the broad view histories. Perhaps that’s because his career took place outside of New York, drawing as he did mostly for the Philadelphia North American, in such comics of his own creation as “Boggs the Optimist” with his catch-phrase,“It could have been worse” (muttered between the fifth story window and the pavement); “Fitzboomski” (putting dynamite in the czar’s punching bag); and “Jingling Johnson,” who cannot express himself but in ceaseless rhyme (“Lincoln freed the blackman, Custer fought the red, Nero wore a sausage turban when he went to bed”). The problem with the approach of following a groove, and it is not a problem we should lose a snooze over, is that the compiler can be tempted to abandon limpidness momentarily to include a personal favorite or two, or a well known figure who will increase demand, who might not exactly fit the corrugation. Thus, while one can posit a line of continuity between Goldberg, Gross and, say, Harvey Kurtzman (the latter not included for reasons of an orderly discontinuance, but certainly the ineludible third term in that sequence), I’m inclined to ask whether George Herriman belongs in it. His humor is the product of a different spirit altogether from that of the other cartoonists here. But then again, what bureaucratic nitwit would prefer cognizability over 18 pages of Herriman’s brilliant “Stumble Inn,” nine of these pages being color Sundays (this book has color all through, hence that lumpy price tag- though Trump’s 25% China tariffs have something to do with it also). Tumey’s Screwball is, in short, entirely a compendium of what Tumey finds risible and antic, and who are we to snivel? - He has been riding shotgun for his conception of “Screwballism” for years now on his blog and otherwhere. It’s the bug in his ear.

Opper is where this new kind of cartooning begins. The difference between his early work and the new style he introduced in March 1900 with “Happy Hooligan,” the tramp who is only trying to help but always ends up with a truncheon on his head, is the difference between two eras, between the somewhat staid Victorian decades, which had not yet figured out how to turn bones to rubber and how to throw the laws of physics out the window. These latter were to be the casual habits of twentieth century animation, and it took an unembarassable American kind of cartooning to get us there.

Opper is where this new kind of cartooning begins. The difference between his early work and the new style he introduced in March 1900 with “Happy Hooligan,” the tramp who is only trying to help but always ends up with a truncheon on his head, is the difference between two eras, between the somewhat staid Victorian decades, which had not yet figured out how to turn bones to rubber and how to throw the laws of physics out the window. These latter were to be the casual habits of twentieth century animation, and it took an unembarassable American kind of cartooning to get us there.

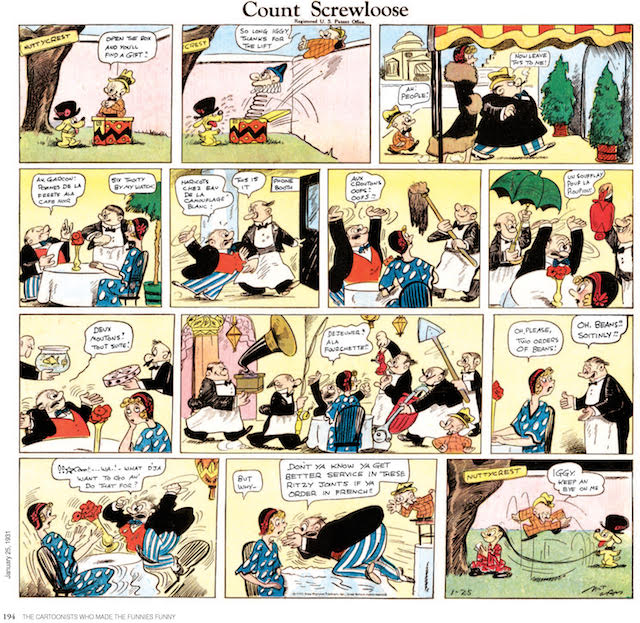

Tumey gives us the big guns of this new era, the heavy stuff: Eugene Zimmerman, or “Zim” in those days of three letter noms de pencil; Rube Goldberg, “The Napoleon of the nuthouse” as Tumey calls him, who has a good solid section including a handful of Boob McNutt color Sundays; Milt Gross, who was irrepressible in such titles as “Count Screwloose,” a character who breaks out of Nuttycrest funny farm in the first panel, gets involved in the daffyness of modern life and is relieved to be able to break back into the nuthouse in the final panel; Elzie Segar, the creator of Popeye, of whom Tumey shines the light usefully on a sampling of his whole oeuvre, in a 5,000 word essay embracing “Looping the Loop,” “Thimble Theater” and “Sappo.” Tumey’s description of Segar’s work reads like a prospectus for the whole screwball project: “Fetchingly distorted forms, exaggerated action, freeze-frames of chaos, silly wordplay, crazy inventions, meta-gags, humorously serious characters, and nonsense galore.”

Tumey gives us the big guns of this new era, the heavy stuff: Eugene Zimmerman, or “Zim” in those days of three letter noms de pencil; Rube Goldberg, “The Napoleon of the nuthouse” as Tumey calls him, who has a good solid section including a handful of Boob McNutt color Sundays; Milt Gross, who was irrepressible in such titles as “Count Screwloose,” a character who breaks out of Nuttycrest funny farm in the first panel, gets involved in the daffyness of modern life and is relieved to be able to break back into the nuthouse in the final panel; Elzie Segar, the creator of Popeye, of whom Tumey shines the light usefully on a sampling of his whole oeuvre, in a 5,000 word essay embracing “Looping the Loop,” “Thimble Theater” and “Sappo.” Tumey’s description of Segar’s work reads like a prospectus for the whole screwball project: “Fetchingly distorted forms, exaggerated action, freeze-frames of chaos, silly wordplay, crazy inventions, meta-gags, humorously serious characters, and nonsense galore.”

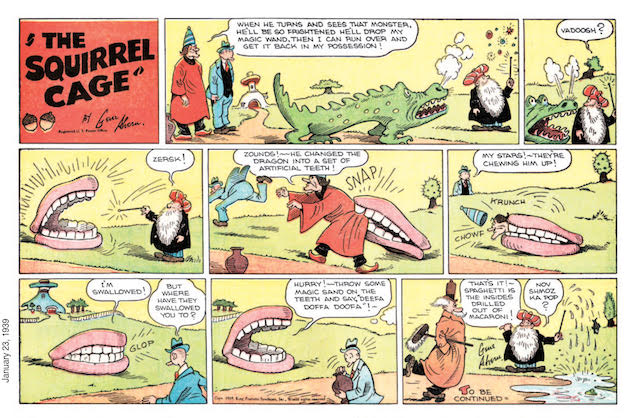

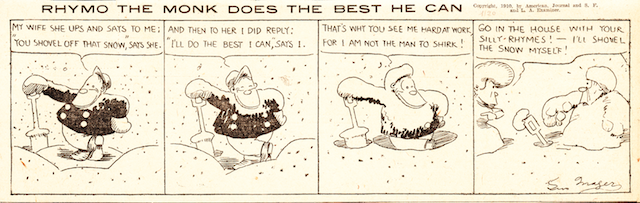

Tumey also gives us the squirts, the small potatoes, though none of them were ever as insignificant as you and me: Gus Mager, whose monkey characters, Rhymo, Knocko, and Groucho, to mention three of his “over thirty silly simians,” inspired the names of the famous Marx Brothers of stage and film; Clare Dwiggins, a great cartoonist who, unknown to me until now, was a dab hand at drawing strikingly beautiful women (with samples); Walter Hoban, perfecter of the “plop take,” the reaction of a character who, upon hearing the punchline, falls, flips, bounces, or rockets into space; Gene Ahern, whose “Ches and Wal, the Nut Brothers,” evolves, in a sequence that would take too long to describe in this context, into “The Squirrel Cage,” a comic whose surreal nuttery would take too long to describe in any context. “The years of strips following this sequence could be interpreted as one long dream...” says Tumey at an early stage of his explanation; George Swanson, creator of $alesman $am and master of the background gag. (Actually, the detail that amused me most about the account of Swanson’s career is when the syndicate editor took him off $am and gave it to cartoonist C.D. Small. At the same time he took Small off “Bugs” and had Swanson draw that. It’s the comics business!); Ving Fuller, who is perhaps the most obscure figure in the book. His ups and downs trying to make a go of the comic strip business make for instructive reading; Bill Holman, whose humor I would say is archetypically screwball. He’s the one you’d reach for to explain what it is, and he was still practicing it in the 1970s when all the other outbursts of Tumey’s beloved screwballism had gone from the funny papers, replaced by wise-ass purveyors of high sarcasm like Johnny Hart. I only ever saw it in its late days on occasions when I obtained a Chicago Tribune funnies section and I confess I found it unbearably old-fashioned and never read it, even if the early Mad comic book guys all raved about it. I’m begrudgingly giving it a better chance now. I see that Holman can’t put a picture on the wall of a room without turning it into a bit of funny business irrelevant to the main point of his comic; and finally there’s Boody Rogers, who brings us at last to the advent of the comic books. I had a hard time taking to Boody Rogers when Dan Nadel published twenty pages of his work in Art Out of Time and I’m still having a hard time. Nadel seems to have wanted to re-toss the supposed “canon” by putting the oddballs front and center for a moment. Oddballs, screwballs: can their zany noncomformity, quieted by time, still show us a way out of the humorless world of conservative gloom encroaching upon us?

Tumey also gives us the squirts, the small potatoes, though none of them were ever as insignificant as you and me: Gus Mager, whose monkey characters, Rhymo, Knocko, and Groucho, to mention three of his “over thirty silly simians,” inspired the names of the famous Marx Brothers of stage and film; Clare Dwiggins, a great cartoonist who, unknown to me until now, was a dab hand at drawing strikingly beautiful women (with samples); Walter Hoban, perfecter of the “plop take,” the reaction of a character who, upon hearing the punchline, falls, flips, bounces, or rockets into space; Gene Ahern, whose “Ches and Wal, the Nut Brothers,” evolves, in a sequence that would take too long to describe in this context, into “The Squirrel Cage,” a comic whose surreal nuttery would take too long to describe in any context. “The years of strips following this sequence could be interpreted as one long dream...” says Tumey at an early stage of his explanation; George Swanson, creator of $alesman $am and master of the background gag. (Actually, the detail that amused me most about the account of Swanson’s career is when the syndicate editor took him off $am and gave it to cartoonist C.D. Small. At the same time he took Small off “Bugs” and had Swanson draw that. It’s the comics business!); Ving Fuller, who is perhaps the most obscure figure in the book. His ups and downs trying to make a go of the comic strip business make for instructive reading; Bill Holman, whose humor I would say is archetypically screwball. He’s the one you’d reach for to explain what it is, and he was still practicing it in the 1970s when all the other outbursts of Tumey’s beloved screwballism had gone from the funny papers, replaced by wise-ass purveyors of high sarcasm like Johnny Hart. I only ever saw it in its late days on occasions when I obtained a Chicago Tribune funnies section and I confess I found it unbearably old-fashioned and never read it, even if the early Mad comic book guys all raved about it. I’m begrudgingly giving it a better chance now. I see that Holman can’t put a picture on the wall of a room without turning it into a bit of funny business irrelevant to the main point of his comic; and finally there’s Boody Rogers, who brings us at last to the advent of the comic books. I had a hard time taking to Boody Rogers when Dan Nadel published twenty pages of his work in Art Out of Time and I’m still having a hard time. Nadel seems to have wanted to re-toss the supposed “canon” by putting the oddballs front and center for a moment. Oddballs, screwballs: can their zany noncomformity, quieted by time, still show us a way out of the humorless world of conservative gloom encroaching upon us?

“Foo” I say, after Bill Holman’s Smokey Stover, or some other character in that strip, and it loses not a jot of its vim and vigor in the repeating.

“Foo” I say, after Bill Holman’s Smokey Stover, or some other character in that strip, and it loses not a jot of its vim and vigor in the repeating.