Having established her comics bonafides with her graphic novel series Angel Catbird, a collaboration with artist Johnnie Christmas, legendary prose writer Margaret Atwood’s second major modern comics work didn’t come as quite as much a surprise, nor did it receive quite as much attendant attention and coverage. That’s understandable, but also sort of unfortunate, as her and Ken Steacy’s War Bears is a comic book about comic book history itself.

That is to say, while Angel Catbird was a pretty pure expression of some of Atwood’s own doodling obsessions (the writer having spent a substantial amount of time in her childhood drawing comics featuring winged cats, for example), War Bears has a broader appeal and much less idiosyncratic (read: weird) hook to it.

It’s the sort of comic book story that will at least be of interest to almost anyone interested in the medium.

This final, graphic novel form is actually the third iteration of the War Bears story. The first was a short prose story, commissioned from Atwood by the Globe & Mail to run in a special edition of the paper celebrating Canada’s 150th birthday. The idea was for various fiction writers to choose a date in Canadian history and build a story from it. Atwood chose May 8, 1945--VE Day. Her story Oursonette covered the celebration of VE Day in Toronto, but from the particularly bittersweet point of view of a young comic book artist. The creator of the popular bear-themed, Axis-smashing super-woman of the story's title, he realized immediately that the end of the war also meant the end of the ban on importing America comic books, and thus the end of the Canadian comic book industry that bloomed to fill in a very temporary void. To illustrate Atwood’s prose, the Globe & Mail hired Ken Steacy, and he drew a full-color image of the comic within the story, banner headline-bearing newspapers and confetti and trash from the street celebrations, as well as two small spot illustrations.

The second iteration of War Bears was a three-issue, serially-published miniseries from Dark Horse in the fall of last year. This builds backwards from Atwood’s prose story, which served as the climax of this second iteration. There’s no breakdown of who did what degree of the writing, but I would guess Steacy’s contributions were quite substantial. He shares a story credit with Atwood, after all, and Atwood’s foreword credits him with the main work on the script. The comics dramatization of scenes in the Globe & Mail story fill but five pages of the overall book. The final iteration is, of course, this collection, which reads like the graphic novel it was apparently written as before being broken up into chapters for the purpose of serialization.

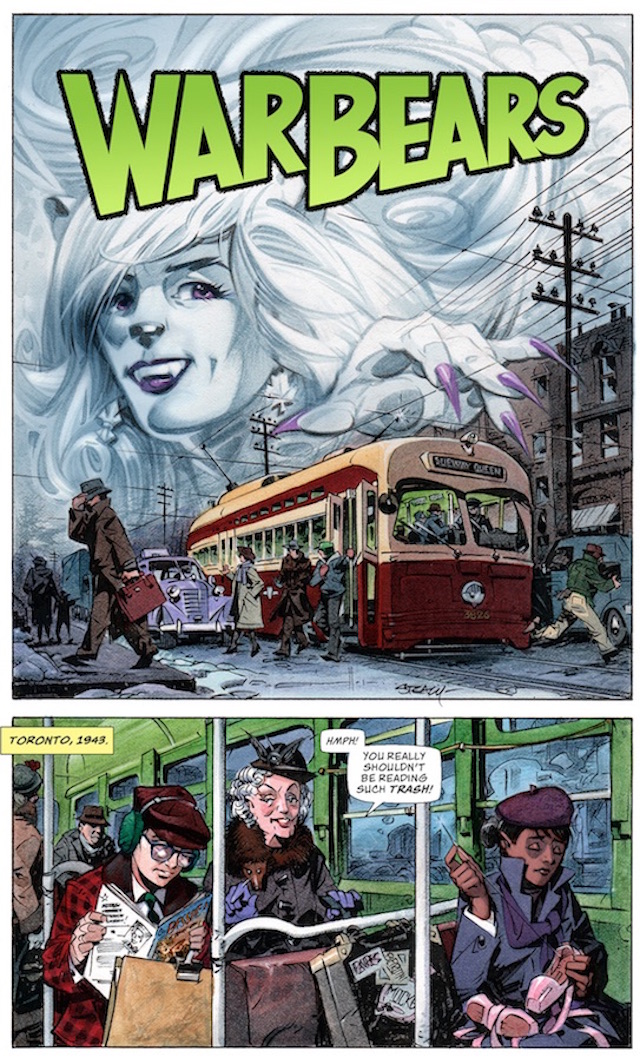

Although all the characters, the superheroine and the comic book publisher are all fictional, the story is basically a true one. Stretching from 1943-45 (with a six-page epilogue set at the 2009 Shuster Awards), War Bears tells the story of the Golden Age of comics in Canada. The basics of the industry were, of course, quite similar to the US version, but in Canada the industry was much shorter-lived and driven by outside factors; the way it basically popped up one year and evaporated a few years later giving it a degree of specialness that Atwood explored in her short story.

Although all the characters, the superheroine and the comic book publisher are all fictional, the story is basically a true one. Stretching from 1943-45 (with a six-page epilogue set at the 2009 Shuster Awards), War Bears tells the story of the Golden Age of comics in Canada. The basics of the industry were, of course, quite similar to the US version, but in Canada the industry was much shorter-lived and driven by outside factors; the way it basically popped up one year and evaporated a few years later giving it a degree of specialness that Atwood explored in her short story.

When Canada passed the War Exchange Conservation Act in 1940, it banned nonessential imports like the four-color adventures of Superman, Captain America, Captain Marvel and company. A handful of Canadian publishers appeared and started cranking out what became known as the “Canadian whites”--cheaply made comics with color covers but black and white interiors. Among the best-known of the heroes starring in these were Nelvana of The Northern Lights, a heroine whose debut pre-dated the more famous Wonder Woman, and whose look and powers resembled those of Wondy’s a bit.

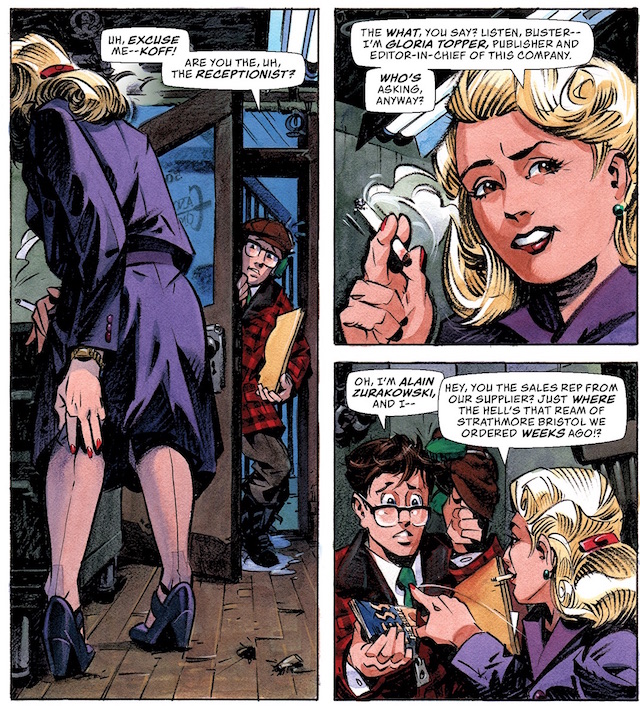

Steacy and Atwood introduce us to Alain Zurakowski, a young Francophone of Polish descent who is unable to fight in the war from a combination of asthma and bad eyes (His ethnicity is important in the story, as it establishes his outsider status in some circles). He applies for a job at Canoodle Comics, a small sweatshop of a studio run by Gloria Topper, who has taken the opportunity created by a country drained of its men to attain a position of relative power in the niche industry. There he meets the third major character, Mike Mackenzie, a square-jawed, overbearing oaf that Alain will spend much of story drawing elbow to elbow with.

Alain creates Oursonette, a Nelvana-like sexy were-bear superheroine who wades into the war to assist Canadian forces and the allies with the aid of her two polar bear companions, and she quickly becomes Canoodle’s top character. In excerpts from her book--presented here in black and white, as they would have been were Oursonette one of the real Canadian whites--and in Alain’s occasional day dreams, fantasies and nightmares, Steacy and Atwood have their Alain working out his fears and frustrations, turning them into puply fight comics. All the while, they tell the story of life on the homefront during the second world war in general, and within the comics industry in particular. And not just in war-time Toronto, but of popular comics over the course of some 80 years.

Alain creates Oursonette, a Nelvana-like sexy were-bear superheroine who wades into the war to assist Canadian forces and the allies with the aid of her two polar bear companions, and she quickly becomes Canoodle’s top character. In excerpts from her book--presented here in black and white, as they would have been were Oursonette one of the real Canadian whites--and in Alain’s occasional day dreams, fantasies and nightmares, Steacy and Atwood have their Alain working out his fears and frustrations, turning them into puply fight comics. All the while, they tell the story of life on the homefront during the second world war in general, and within the comics industry in particular. And not just in war-time Toronto, but of popular comics over the course of some 80 years.

At the beginning of War Bears, Alain encounters a woman on a bus who tells him he should be ashamed of reading comics at his age, as they are a source of juvenile delinquency and “moral decay.” Because of the relative contempt for the medium, Alain is among the relatively undesirable employees who manages to find a place to work and to allow his art to flourish, and he is able to filter his own personal politics and worldview into his comics, turning it into wartime propaganda...and, later, investing more of himself into it, as the unifying effects of the war effort dissolve (the last excerpt from an Oursonette comic deals with the advent of the atom bomb, with the characters fretting over the two paths that atomic energy have revealed for humanity).

The comics are unappreciated--or at least under-appreciated--by seemingly everyone, even most of the people making them, and when the war ends, Glory, Alain, Mike and company abandon the comics and pursue other, more traditional and respectable avenues of commercial art. Decades later, Alain is inducted into the Joe Shuster Awards hall of fame, where he’s feted by Gloria’s granddaughter, now a successful graphic novelist who says she drew inspiration from Alain’s work and his creation and presents the award to him while cosplaying as Oursonette. The character and the comics, once created by desperate outsiders for a market of children and war time pop propaganda, have eventually earned the acceptance of the mass culture. Comics, in other words, won...eventually. (I suppose to make that victory complete, there could have been a second epilogue, showing Alain walking the red carpet at the opening of an Oursonette movie).

Steacy and Atwood give their characters a happy ending, and it’s certainly their right to end their story how they like, although for every Alain there were a handful of Joe Shusters. We don’t see what happened to Alain between the last issue of Oursonette and when he gets a phone call from the Shuster Awards people, but he seems to have had an okay life. He was still alive in 2009, after all, and living on his own in a well-appointed apartment.

Steacy and Atwood give their characters a happy ending, and it’s certainly their right to end their story how they like, although for every Alain there were a handful of Joe Shusters. We don’t see what happened to Alain between the last issue of Oursonette and when he gets a phone call from the Shuster Awards people, but he seems to have had an okay life. He was still alive in 2009, after all, and living on his own in a well-appointed apartment.

That ending, as too-perfect as it might seem, is also reflective of another element of the book, wherein the characters exhibit foreknowledge informed by the creators’ own hindsight. On VE Day, for example, Gloria is already predicting Oursonette’s bear theme won’t be so popular any more, as she expects the Americans and the Soviets to start dividing things up and be at one another’s throats in a cold war soon enough. She also anticipates the coming wave of consumerism that will follow the last years of deprivation, as mid-century North America goes appliance crazy.

Similarly, Alain alone seems to have seen the future of the comics medium, and considers what he is doing important, high art. He only reluctantly rips up Oursonette pages upon Gloria’s orders, so no one ever tries to fish them out of the trash and tries to reprint them without permission. “But, but don’t you think they might be worth something, some day?” he protests. “Ha! In your dreams, Picasso,” she replies.

Similarly, Alain alone seems to have seen the future of the comics medium, and considers what he is doing important, high art. He only reluctantly rips up Oursonette pages upon Gloria’s orders, so no one ever tries to fish them out of the trash and tries to reprint them without permission. “But, but don’t you think they might be worth something, some day?” he protests. “Ha! In your dreams, Picasso,” she replies.

In the first iteration of this story, Atwood’s prose version, we meet a broken-hearted Alain, seemingly the only person in a bad mood in Toronto on VE Day, as he’s keenly aware his dream job is about to disappear. In this final iteration, Steacy and Atwood show us why Oursonette and comics meant so much to Alain, and grant him a happily ever after that is more saccharine than bittersweet.

It’s wish-fulfillment nature seems somewhat discordant, but what are superhero comics but wish-fulfillment? Like Oursonette herself, War Bears’ Alain is presented as something of a superhero...albeit of a very different kind.