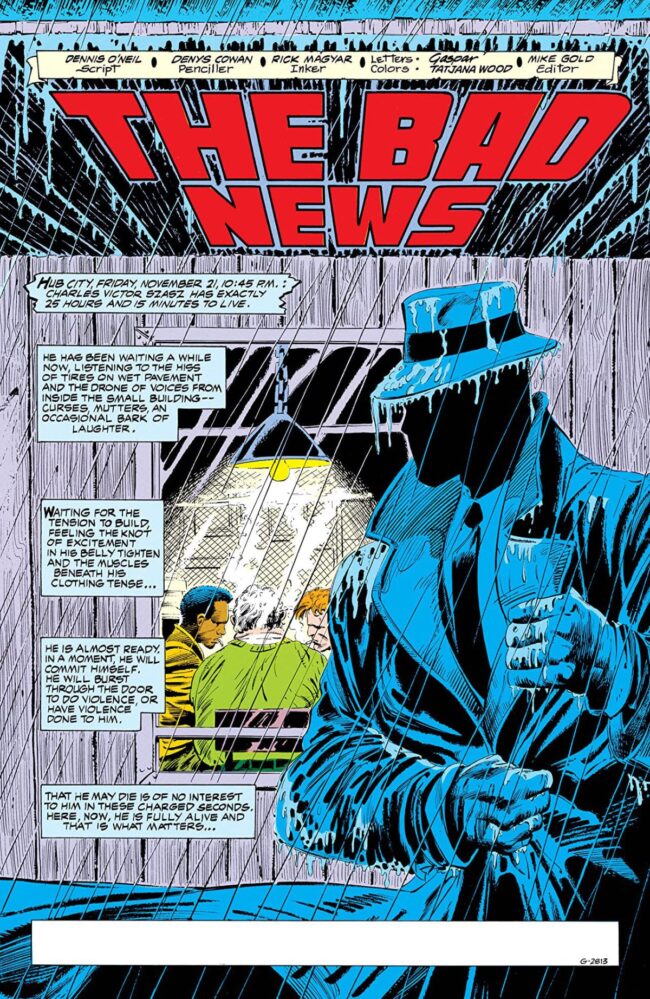

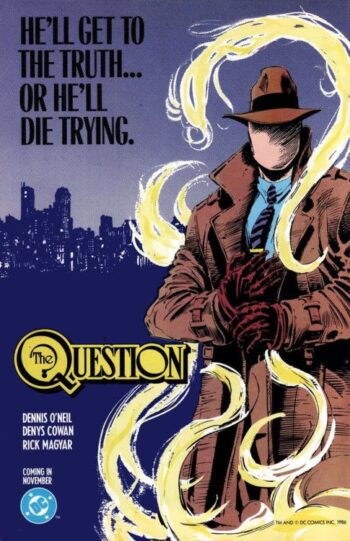

Denys Cowan has done so much in not just comics but in art and animation that it can be hard to keep straight. For some people he’s best known as a producer and director of acclaimed animated shows like Static Shock and The Boondocks. Others know him for the legendary run of The Question, that he made with writer Denny O’Neil in the 1980’s. Cowan drew Batman: Blind Justice, written by Sam Hamm, a run on Steel, written by Christopher Priest. Cowan drew Power Man and Iron Fist and Deathlok and Black Panther. He drew the art for GZA’s Liquid Swords album and a comic book of Prince. In short, for people my age and younger, Cowan has always been one of the greats.

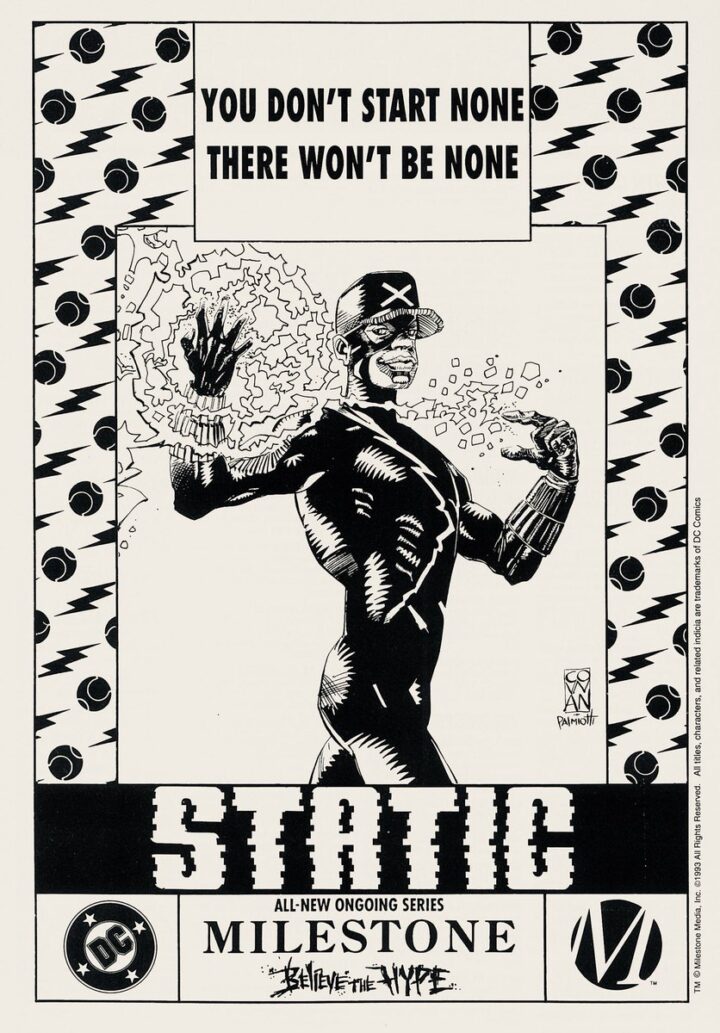

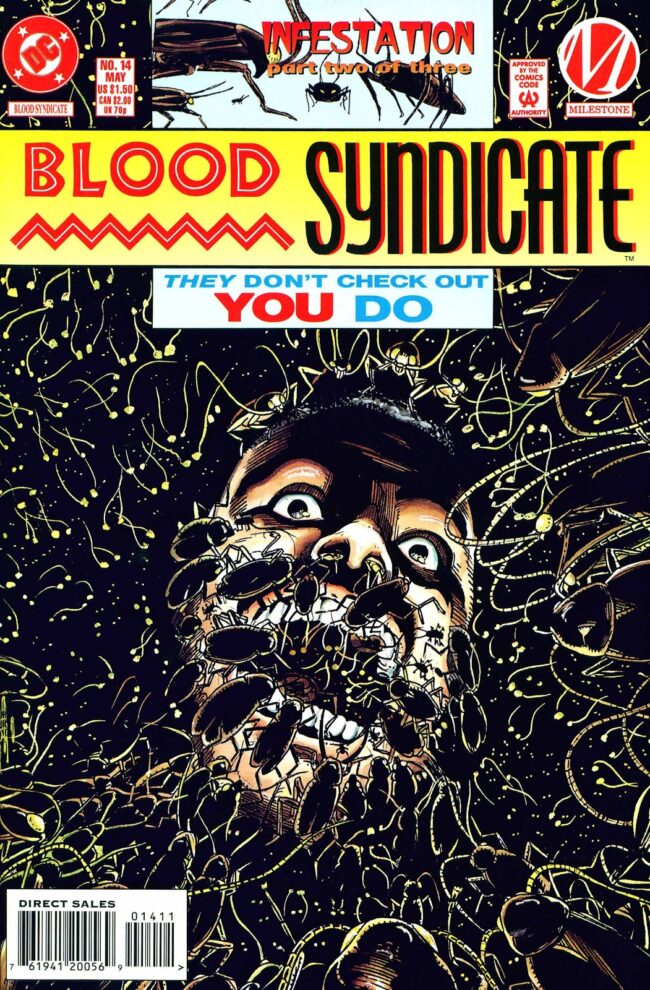

But he will forever be known as one of the co-founders of Milestone Media with Dwayne McDuffie, Michael Davis, Derek T. Dingle, and initially, Christopher Priest. Milestone helped change the face of comics in ways that go far beyond the sheer amount of talent who worked for the company, including Ho Che Anderson, M.D. Bright, Crisscross, John Paul Leon, Shawn Martinbrough, Jimmy Palmiotti, Humberto Ramos, John Rozum, Ivan Velez Jr., J.H. Williams III. To say that the Milestone creators wanted to make comics about real issues misses the point and undersells what their ambitions – they sought to expand what comics could be. The books took a lot of the implicit biases and ideas of superhero comics and asked questions about the police and the rule of law, poverty and gentrification, state violence and the importance of found family. They manage to question and embrace some of the silliness of the superhero concept. One issue of Icon took aim at Luke Cage in a way that paid tribute to what he did and represented, but wasn’t blind to the flaws and limitations of the character. It was a bold approach and when the company relaunches early this year, we shall see what they do in a new era.

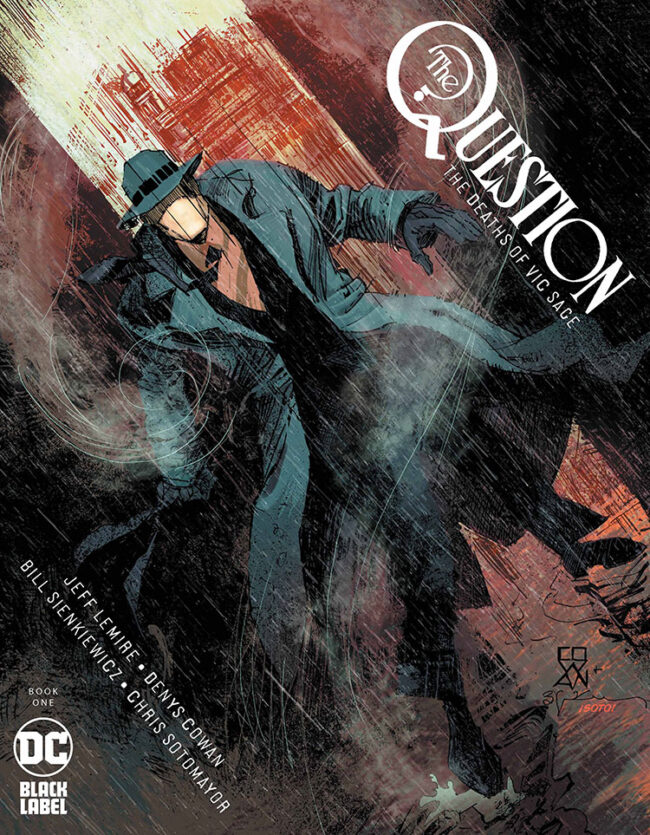

Recently Cowan returned to The Question in a limited series written by Jeff Lemire and inked by Bill Sienkiewiecz, and 2021 will see the return of Milestone with a new Icon and Rocket series drawn by Cowan, among other projects. Everything old is new again, Cowan joked at one point. We’ve talked in the past and did this interview over the course of the year, talking about his collaborations with two of comics’ greatest writers, Dwayne McDuffie and Denny O’Neill, how Howard Chaykin changed the way he thought about art, and not being comforting.

I know a little about your background. You grew up in New York and attended the High School of Art and Design. I know you worked for Rich Buckler for a while.

I started working for Rich when I was going to the High School of Art and Design. I was a sophomore. A friend of mine at the time, Armando Gil, was working for Rich and another artist named Ken Langraf. He was going to meet Ken and Rich and asked me one day if I wanted to tag along. Rich Buckler was one of my heroes at the time from Deathlok. I was the king of tag alongs back then at fourteen-fifteen, so I went with him to uptown Manhattan and met Ken and Rich. I walked into Rich’s apartment and he was working on if I remember correctly the Gorilla Grodd issue of some Superman comic. I just remember gorillas and thinking, I can’t draw gorillas like that. I wish I could draw gorillas like that. It started from there. Armando was working for Ken and Rich offered me a job – at fourteen – working for him as an assistant. He already had a couple of assistants and my basic job – because I couldn’t draw at all, really – was to run errands, get coffee, find reference, find comic books reference, cut things out, paste things down, stay out of the way. That was my job. I think I did that very well. [laughs] It was a real learning experience with Rich, I have to say.

How long were you working for him? Through high school?

From fourteen until I was fifteen. About a year of working for Rich. Continuity Associates had an internship opening and basically that deal was you could go to school but get school credits by working at this art studio. Since I had been in comics working with Rich and I knew some people, I was able to get a job working at Continuity for school credit. So I started working for Neal Adams when I was 16 years old. I spend a good deal of time bouncing between Rich and Continuity and then it was all Continuity. That was I think I did that until I was seventeen-eighteen-nineteen. A good three or four years of Neal putting up with me.

Had Continuity started publishing comics at that point?

I think they had. I think they were doing Ms. Mystic and a couple of other things. Mike Nasser was there at the time. Joe Barney. Greg Theakston. Mike Higgins. Gray Morrow. Sergio Aragones. I met everybody at Continuity. Russ Heath was working there when I was working there. Carl Potts had an office in the back. Marshall Rogers was doing Batman at that time. It was a rich time in comics. I think Neal was getting his publishing thing together. I know he was working on a lot of his own characters like Bucky O’Hare. The first time I saw Neal he was coloring the cover to Superman vs. Muhammed Ali. I was watching him work on this massive project and my mind was just blown.

I’ve heard stories about Continuity. People having desk space there and working. People stopping by with portfolios.

I had desk space there because I was working as an intern. People did rent space there. Some people would just show up and hang out. It was really a meeting space for artists. That first day I started, Dick Giordano was still Neal’s partner and I had the distinct pleasure of Dick Giordano kicking me out of Continuity. [laughs] He was like, who is this kid? Get him out of here. But then I came back. It didn’t mean anything to me getting kicked out by Dick Giordano. It just meant I had to come back and try again. People were renting space and it was a very loosely-structured, tight-knit community, if that means anything. It was a great time to be in comics and be around those people.

I’ve heard stories of Neal going through people’s portfolios and he even if they weren’t quite there, he would make a call and say, the person’s got talent at inking or lettering, I’m sending them over to you.

I was working at Continuity when Frank Miller came up for the first time and when Bill Sienkiewicz came up for the first time. I’d seen Bill before. I was at DC when I was working for Rich and I remember this guy coming up in a suit and a portfolio. This white dude looking very professional. He was waiting in the lobby with us and I looked like whatever I looked like back then, wearing a baseball cap or something. He gets shown in and I remember thinking, this guy looks sharp. I didn’t think anything else about it, but months later I’m working at Continuity and that guy walks in. He had an appointment with Neal Adams. There was a front room at Continuity where Neal would work. Joe Barney was there. Russ Heath had a desk in the front room. I had a desk behind Neal because I was doing a lot of coloring and assistant work. I think Neal kept me close by so he could fix everything. This guy walks in, puts his portfolio down, Neal starts looking at all these pages, and calls us all over. Everyone in that front room – I don’t think Russ went – we went to look at his portfolio, and this guy could draw. I’m looking at it and going, I give up. Neal said, look at this guy’s work. He’s doing me in the right way. I’m obviously an influence, but this guy is good and I wanted you to see it to see what you could do if you applied yourself. [laughs] Neal picked up the phone and called Jim Shooter and said, I’m sending over a guy you need to see. Bill went over there and got Moon Knight. I was there. I saw the whole thing. Frank Miller was a similar story. I think Frank had some Gold Key jobs under his belt, but he came up and showed Neal his stuff. I remember looking art Frank’s art and his layouts, his sense of design was incredible. Neal picked up the phone and called Jim Shooter and said, I’ve got a guy for you, and sent him over. He never called anyone for me, though. I wish he would have.

And he didn’t just call an editor.

Yeah, he didn’t call an editor, he called Jim Shooter! [laughs]

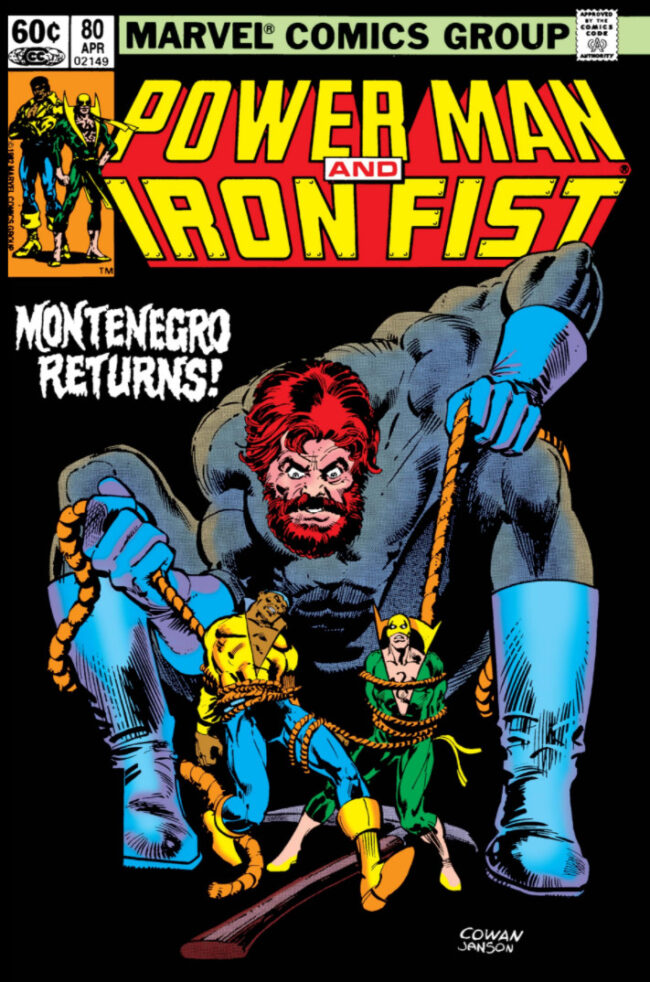

You drew short comics and fill-ins for a few years before you had a run on Power Man and Iron Fist.

You drew short comics and fill-ins for a few years before you had a run on Power Man and Iron Fist.

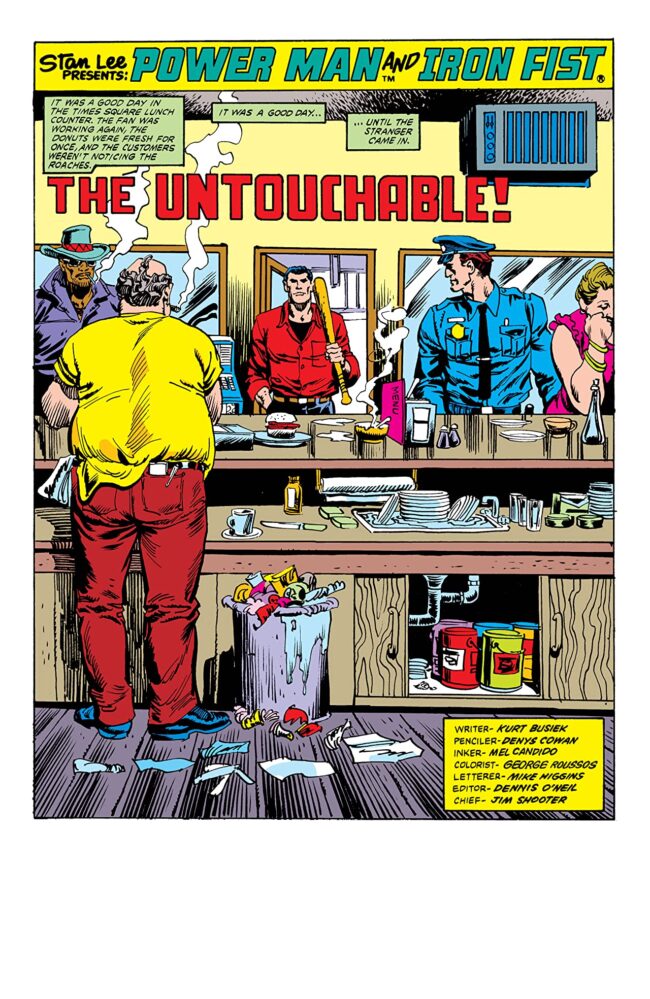

The first thing I did for Marvel was a Hulk pin-up. They had a black and white Hulk magazine. I was seventeen. I forget who the editor was, maybe Bob Budiansky? I slaved over that pin-up for a week. Joe Rubinstein inked it. I waited two years for that thing to see print. [laughs] I don’t if it ever got in print. Maybe it did? I think I did a bunch of shorts for DC. That was how they trained people back then. I was 17 and I worked for Joe Orlando and Julie Schwartz up at DC. They would give me seven or eight page jobs. Superman 2020. A Firestorm story in the back of The Flash. An Elsewhere story starring Superman. Stuff like that. They would give you these jobs, beat your ass over it when you handed it in. Just tear it down and destroy it over and over until they got these eight pages the way they wanted to see them. Especially Joe Orlando. I can’t tell you how many time he would take a piece of tracing paper, put it over my pages, and show me how to do the panels in the right way and what I should be looking at. I would go back and trace that and re-do it. I’ve said this before, the way you knew that you did well was they would never tell you that you did a good job. They would just open a drawer, pull out another script, and hand it to you. That was how you knew you did okay. You got another eight page script to get beat up over. [laughs] After doing that for a year or two, I finally got a chance to do my first book, which was Power Man and Iron Fist at Marvel. Jim Shooter gave me that one personally, which was pretty cool.

Denny O’Neill was your editor.

Denny O’Neill was the editor and Mary Jo Duffy was the writer at the time. She was terrific. Her scripts were terrific, but I didn’t appreciate them at the time. I thought everything had to be super-serious and super-hardcore and she was really treating the whole thing like a Bob Hope-Bing Crosby on the Road kind of thing and finding humor in their situation. I wasn’t a really funny guy. It was always a struggle working on her scripts – not because of what she did, because she was brilliant, but because of my attitude about it. That being said, I look back on those scripts and that work now and I know those scripts were great. I wish I would have done a better job for her on those. That being said, it was a great series to do and I had a lot of fun. And I learned a lot.

As far as the humor, you’re not known for being a funny artist, was it struggling with the tone?

As far as the humor, you’re not known for being a funny artist, was it struggling with the tone?

It wasn’t struggling with the humor so much as it was figuring out the humor, and how it applied to Power Man ands Iron Fist. I was like, this is Power Man and Iron Fist. These should be serious stories. To me, it should have been more like the Netflix shows than comedy. But if I had to do it again, I would lean into the comedy more. [laughs] Try to get more of a light hearted aspect to it because everything else has been done to death. Why not? But hindsight is 20/20.

In the few years between Power Man and Iron Fist finishing and launching The Question, what were you working on?

In the few years between Power Man and Iron Fist finishing and launching The Question, what were you working on?

I did Power Man and Iron Fist and then I did a Black Panther miniseries at Marvel. Me and Peter Gillis. Because of my state of mind at the time, I said, if we’re going to do a story about a Black African king, we need to deal with what’s going on in Africa – like Apartheid. We did three issues of that right after Power Man and Iron Fist finished. I busted my ass on this and then Jim Shooter called me into his office and said they weren’t going to publish it. I said, why not? He said, because this deals with Apartheid and racism in South Africa, and we sell a lot of comic books in South Africa. I looked at him like, wow. He said, we’re going to shelve this, and it was shelved. After that, I went onto do The Question and Batman and four years later or something like that, Tom DeFalco approached me. At this point Jim was gone, and Tom asked me to finish the miniseries. So I drew the last issue, the fourth issue, years after I drew the third issue. My whole style had changed, my attitude towards drawing had changed, everything had changed. It was a very odd pairing if you look at that work. The reason there’s such a difference between the first three and the fourth issue its that years had passed! Why they asked me to pick it back up after all those years and do it again, I have no idea. It came out the way we had written it, with the supremacist villain group and Apartheid as the central theme and racial injustice as the core of the message. But why they made that decision to bring it back, I don’t know. It may have been the success of The Question and Batman or whatever I had done. Or maybe they just needed some inventory? Who knows? That’s what I did right after Power Man and Iron Fist and then it was onto The Question with Denny O’Neil. Running into Denny again.

Did you also draw a series for Epic in this time?

Yes. It was for the Shadowline saga. Epic was doing some comic books, Saint George, Doctor Zero, and a third one. Archie Goodwin was the editor there and Dan Chichester and I want to say Margaret Clark were the writers and editors. Archie asked me to do Doctor Zero and I asked Bill [Sienkiewicz] if he wanted to ink it and he said sure. We did three or four issues of Doctor Zero, and it was fun. I did one issue of Saint George with Kent Williams, but the rest were done with Bill Sienkiewicz.

Was that the first time you and Bill worked together?

On interiors. This was 1990 or so? We had done The Question covers but we had not done any interior artwork up until that point. I think some of that artwork still holds up. Not for what I did, but the skill that Bill brought to it was incredible. He was always the man.

I read somewhere that you were not the original artist on The Question.

I was not.

So how did you get the job?

I have no idea. [laughs] I don’t know, but I can tell you the circumstances. Basically this was 3 or 4 o’clock on a Friday afternoon. I don’t know why I was at DC. I was handing in something and was told to stick around because Dick wanted to talk to me. I’m thinking, what did I do? I hope he doesn’t throw me out again. [laughs] That’s what I was thinking. Still all paranoid from that. Dick had me come into his office, sat me down, and said, do you know the character The Question? I said, sure, that’s Steve Ditko’s thing. He said, we’re doing this book and the original artist can’t do it. Ernie Colon was supposed to be the original artist and I think he was under deadlines. I don’t know whether it was because I was in the office at the time – so it could have been Norm Breyfogle or anybody – but he asked me if I’d be interested in doing it. I said, sure, because I was willing to do anything. I had no idea what I would do. I knew the guy had a suit and a hat and I knew nothing else about him. But me saying yes totally changed my life. That’s how I got it. They were desperately searching around for an artist on a Friday afternoon and I happened to be in the office. I had done a couple of issues of V for DC. I had done Vigilante. I had done a couple issues of Teen Titans starring Starfire. Dick had inked my work. I had worked for DC, I had just never done a regular book for them.

So you didn’t know know Denny was writing it or anything else, you got offered a gig and you said, yes.

I have told this story. When I was on Power Man and Iron Fist, Denny O’Neil was my editor and to say it was an experience would be an understatement. I didn’t know anything about drawing comic books, really, and Denny knew a lot. He was so patient with me, but he stayed on my ass. Now I realize he was trying to get me to make my deadlines and turn me into a professional artist. He had deadlines he had to make to get this book and here I am agonizing over panels or whatever. He straightened me out real quick. I lived through that. I went on to do all this stuff at DC and then I get this wonderful opportunity. They wanted me to draw The Question. So I come in on Monday to pick up the script and Dick brings me right to Denny O’Neill’s office. I’m thinking, oh my god. [laughs] Denny O’Neill is writing the scripts for this thing! Mike Gold was the editor. Denny was an editor at DC at the time but he was also writing this book and I got to relive that again for three more years. [laughs] Except this time it was Mike Gold and Denny O’Neill who insisted I never did anything right. [laughs] That was quite the experience. It was a nightmare. A good nightmare, but a nightmare.

Besides them kicking your ass on a monthly basis, what did you think of the book? Were you enjoying drawing it? Because it is this dark noirish book.

Esoteric dark noir. I enjoyed the book very much. My experiences of working on it are different from people reading it. I’ve said that my memories of that book are literally about always trying to meet deadlines and be a better artist. Trying to make what Denny wrote work. Trying to understand what he wrote. There were things that we were doing that were innovations that at the time. Stylistic things that required you to do extra work. Like there were no sound effects in The Question. No bam, pow, slap. So everything you drew had to be crystal clear. So clear that you could hear the sound effects in your head. I struggled with trying to make the work really good and understandable. I didn’t pause a lot to ponder the meaning of the scripts or the words – except to the extent that I had to draw them. It was years later when I went back and read the stuff with fresher eyes that I realized, wow, we were really talking about deeper stuff than I thought back then. Denny was simply brilliant. Simply brilliant. So my experience of working on the book was not being aware of how high brow it really was and just focusing on getting the work done.

In your experience is that, to some degree, just the experience of working on a monthly book? Where you don’t necessarily have time to sit back and consider?

At that time, it did. It was all I could do to focus on getting the thing done. Now it’s similar, but because I’ve done it for a lot longer I can kind of sit back and appreciate a little bit more. Understand the writing craft and see how to make this even better because of my understanding of it. Now it’s an easier process. Slower, because I know more. [laughs] But also easier, because I know more.

The Question was this very noirish book and it changed and your style changed while you were drawing it. How were you working back then?

I started The Question with a specific set of influences, and by the time it finished I had replaced a lot of those influences, or added onto them. When I started The Question my influences were Garcia-Lopez and John Buscema and Neal Adams. I loved Gil Kane. Klaus Jansen and Gil Kane is a combination I still look at to this day about how to do comics. My influences weren’t as much about the design aspect as about drawing figures. As I was working on The Question I was exposed to different influences. I was exposed to a lot of European artists, a lot of Italian and Spanish artists. Sergio Toppi. Dino Battaglia. Jean Girard, aka Moebius. Breccia. Their thing was drawing but also designing a page. Leading your eye from this panel to that panel. Once those influences started coming in, my work changed. It changed drastically because I started seeing things in terms of shapes instead of figures. One of the biggest lessons I ever had in terms of that took place around that time, early on in The Question. I was sharing a studio with Bill Sienkiewicz and Michael Davis. Can you imagine that? [laughs] Those were crazy times. Our studio was right next to Howard Chaykin, Jim Sherman, Frank Miller, Walt Simonson. I was there every day. [laughs] I would show my stuff to Walter and Howard.

Just an aside, the first savage criticism of my work I ever got, someone who completely tore me down, was Walt Simonson. I was already doing Power Man and Iron Fist and I thought I was the shit. I was Denys Cowan. You couldn’t tell me nothing. Well, very confidently I showed my pencils to Walt Simonson. One of my artistic heroes. He was at Marvel, leaning against a wall, probably waiting for an editor or a check. I handed him this stack of pages and he looked at it and then proceeded to tear down page by page, panel by panel, all the things I was doing wrong. This is published work and I was like, oh. [laughs] I was devastated, but I learned so much from that one conversation. So now I’m working next door and I don’t dare show Walt my work, but I would always bother Howard Chaykin. Michael and I were always bothering him. One day he asked, what are you worked on? So I showed him The Question and he looked at my pages and told me I was doing it all wrong. I said, what do you mean? Thinking, here we go again. [laughs] Howard taught me very simply to stop thinking in terms of people and figures and start thinking in terms of shape and design and layout. People are objects and things are objects and they fit in a panel in a certain way. That certain way has to do with design, with leading your eye from this place to that place. Where you put blacks. Where you put objects. What does this mean. He broke it down for me in a good couple hours and that one conversation profoundly changed everything for me. I started looking at other people’s work with a different eye. Not just how they drew stuff, but an overall approach to how they approached drawing and how they approached the page. Artists who were my favorites at the time quickly fell by the wayside, replaced by artists I hadn’t even looked at before, but then and now have influenced me greatly. That was my experience doing The Question. The arc of learning on that project was incredible. It was due to people like Walter and especially Howard. I still owe them a debt for taking the time and being very patient with me.

Just an aside, the first savage criticism of my work I ever got, someone who completely tore me down, was Walt Simonson. I was already doing Power Man and Iron Fist and I thought I was the shit. I was Denys Cowan. You couldn’t tell me nothing. Well, very confidently I showed my pencils to Walt Simonson. One of my artistic heroes. He was at Marvel, leaning against a wall, probably waiting for an editor or a check. I handed him this stack of pages and he looked at it and then proceeded to tear down page by page, panel by panel, all the things I was doing wrong. This is published work and I was like, oh. [laughs] I was devastated, but I learned so much from that one conversation. So now I’m working next door and I don’t dare show Walt my work, but I would always bother Howard Chaykin. Michael and I were always bothering him. One day he asked, what are you worked on? So I showed him The Question and he looked at my pages and told me I was doing it all wrong. I said, what do you mean? Thinking, here we go again. [laughs] Howard taught me very simply to stop thinking in terms of people and figures and start thinking in terms of shape and design and layout. People are objects and things are objects and they fit in a panel in a certain way. That certain way has to do with design, with leading your eye from this place to that place. Where you put blacks. Where you put objects. What does this mean. He broke it down for me in a good couple hours and that one conversation profoundly changed everything for me. I started looking at other people’s work with a different eye. Not just how they drew stuff, but an overall approach to how they approached drawing and how they approached the page. Artists who were my favorites at the time quickly fell by the wayside, replaced by artists I hadn’t even looked at before, but then and now have influenced me greatly. That was my experience doing The Question. The arc of learning on that project was incredible. It was due to people like Walter and especially Howard. I still owe them a debt for taking the time and being very patient with me.

You can see your art shift over the course of the book. For most artists if we’re talking about a run of a few years, most have some kind of shift.

Do you think so? I guess it’s hard not to have some kind of change. You might see some incremental changes, subtle approach. Other artists make a more drastic change. I was one of those people who if you look at it, it was a more drastic change. Or maybe it was subtle, but it definitely started out one way and ended up another way. And not bearing a whole lot of resemblance to the way I used to do it.

I didn’t read them monthly, but I think it worked reading them collected, because Vic was changing, change was part of the book, and I think the art style shifting worked better than on a lot of books where it might have been more jarring.

You’re right. The nature of the book – the noir nature, the Vertigo-before-Vertigo nature – leant itself to a different artistic style. I wasn’t doing anything conventional after a certain point. The subject matter allowed me to get away with a whole lot of stuff like that.

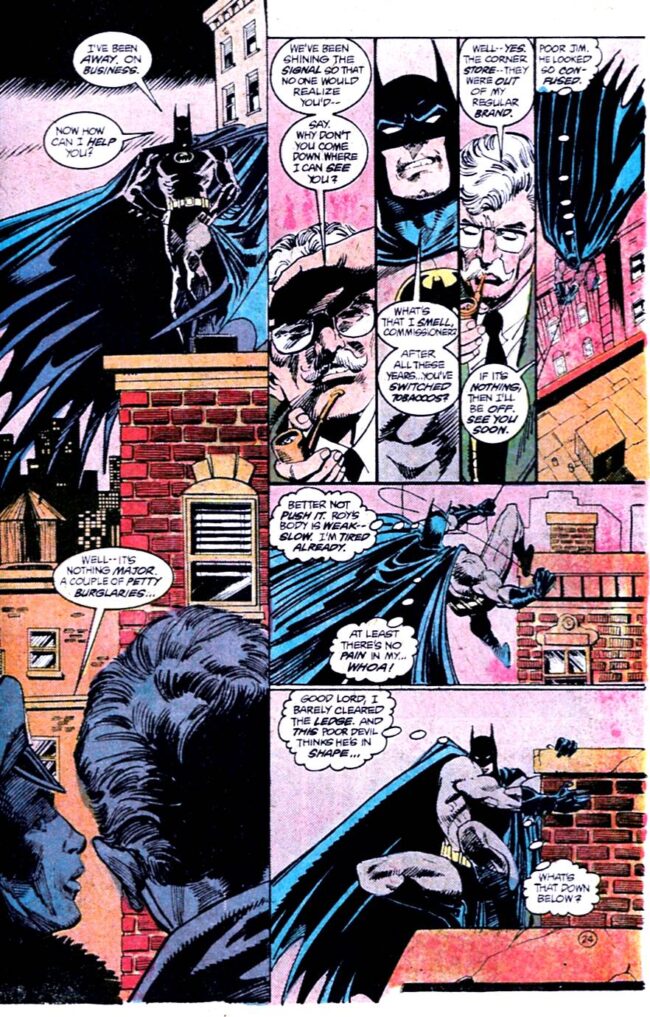

And partway through that, you drew Batman. Was that because of Denny O’Neill?

And partway through that, you drew Batman. Was that because of Denny O’Neill?

That was a crazy time. Maybe two thirds into The Question, they needed an artist to do Detective Comics #598-600. Norm Breyfogle was the artist on Detective and I always thought Norm was awesome. I think they wanted him to get ahead on deadlines so they wanted a fill in artist to do these three issues and they called me into do it. Sam Hamm was the writer so it wasn’t even the regular writer. It was Sam and me, this one-off thing. It was a lot of fun. I took a lot of the stuff I learned on The Question and was able to apply it to Batman. I worked with Dick Giordano, who inked the whole thing, so I got to work with a legendary inker. It was just great. I don’t think Norm was too happy with it. I mean, he was the regular artist on the book and he didn’t get a chance to do that. That was one of those books that sold hundreds of thousands of copies.

It was an event. It was an anniversary issue.

Exactly. Issue #600. It was a big deal. At the time, I didn’t really know it was a big deal. At the time it was just an assignment. But it was great.

When The Question wrapped up, you went back to Marvel?

Well, I went to whoever paid me. [laughs]

[laughs] Did you draw Deatholok right after finishing The Question?

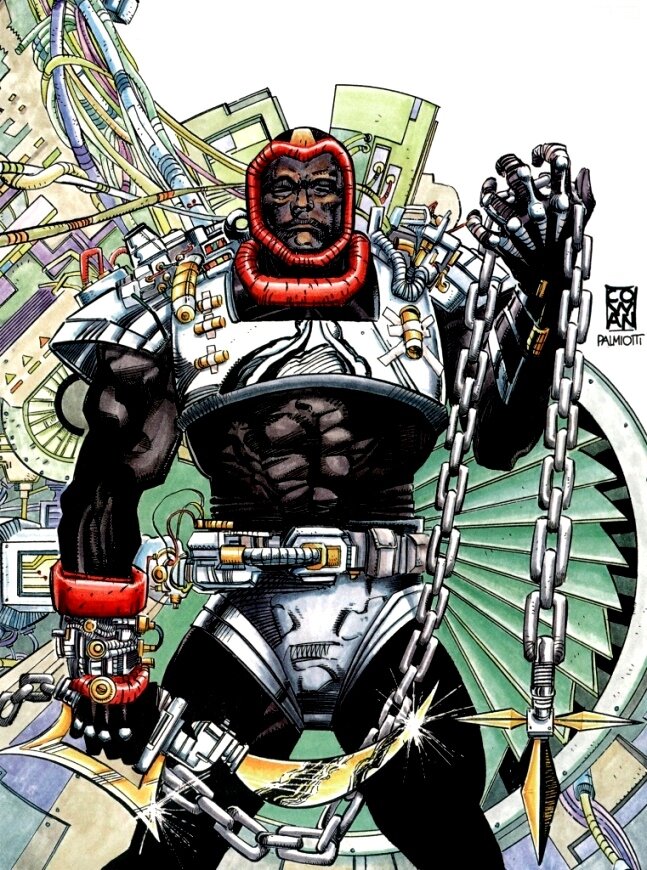

Yes! That was a whole other thing. The Question wraps up, I finished Batman, and I get a call from Marvel. From Bob Budiansky. They’re looking for an artist to come and help out on Deathlok. Jackson Guice had done the first two issues of the miniseries. Dwayne McDuffie and Greg Wright were the writers. I think he was falling behind, I don’t know, but they asked me to help out on the last two issues. That was my first chance working with Dwayne and my first chance working with Greg. But that was how I met Dwayne McDuffie. Again, a life changing experience. I did the last two issues of the miniseries and then Marvel picked it up as a book. They asked me if I would be willing to draw it. So I got to work closely with Dwayne and Greg. The first story arc we did I think was The Souls of Cyberfolk. That was a takeoff of W.E.B. DuBois’ The Souls of Black Folk. And we never looked back. We just went for it. We barely knew each other, but we knew what we wanted to do. And we did.

You two made the Prince comic around that time.

Did I?

I have a publication date of 1991.

I associate Prince more with Milestone, but I could be wrong. That came about because Prince was coming out with a new album and he was with the Warner Brothers label. I don’t know who had the idea of doing a comic. I don’t know if Prince wanted to do it or they pitched it to him, but I got wind of it. They asked me if I’d be interested and I did some sample drawings. Prince approved those drawings and I got the job. Dwayne was picked as the writer and Kent Williams was the inker. I think Noelle Giddings colored that, but I could be wrong.

I don’t know if Dwayne talked with Prince or just his people. I never got a chance to. I just did the drawings and sent them in. I know that Prince approved everything. The lack of comments from Paisley Park meant I was not messing it up. [laughs] We finished the book and the book had not come out yet, but we were contacted by Prince’s management. Prince was giving a concert at the Palladium at 12:30 in the afternoon for these underprivileged school kids, would you like to come? No one knew about this concert. We show up and Prince is shooting a music video with these kids. They stuck us in the front row. Prince did a whole set maybe three feet away from me. Later that night I went back to the Palladium and Prince performed with Lenny Kravitz. I have very fond memories of doing that book. At the time it was an assignment, it was Prince, it was great, but it was an experience.

I don’t know if Dwayne talked with Prince or just his people. I never got a chance to. I just did the drawings and sent them in. I know that Prince approved everything. The lack of comments from Paisley Park meant I was not messing it up. [laughs] We finished the book and the book had not come out yet, but we were contacted by Prince’s management. Prince was giving a concert at the Palladium at 12:30 in the afternoon for these underprivileged school kids, would you like to come? No one knew about this concert. We show up and Prince is shooting a music video with these kids. They stuck us in the front row. Prince did a whole set maybe three feet away from me. Later that night I went back to the Palladium and Prince performed with Lenny Kravitz. I have very fond memories of doing that book. At the time it was an assignment, it was Prince, it was great, but it was an experience.

As far as Milestone, I know people have asked, why did they start Milestone? I always say, did you read Hardware #1? It’s all laid out there.

[laughs] It sure does.

But practically speaking, how did you and Dwayne and Michael Davis, Derek Dingle, and Christopher Priest come together?

It was my idea. The whole thing originally grew from a surprising source. It was 1988 or ’87 and I was at New York Comic Con. I had already done The Question and I was wandering around the con and in this room was Jim Steranko. I knew Jim from at Continuity. He would come through with Pauline, his assistant at the time, and I was in awe of Jim Steranko. Like we all were. Chandler. Nick Fury Agent of SHIELD. Outlander. Everything he ever did. He’s Jim Steranko. He’s on a different level. I wandered into this room and Jim had this display and his art was on a table under plastic so you could see it but you couldn’t touch it. He came up to me and I think I might have called him Mr. Steranko. He pulled me to a corner and I’m thinking, why is Jim Steranko pulling me into a corner? He says to me, the people at DC or Marvel – I think it was DC? – have approached me to create some Black superheroes for them. It occurs to me that I might not be the right person to do that for them. Do you know anyone who might be the right person to do that for them, Denys? I looked at him as he’s looking at me unblinking. I said, I think I might know someone. He said, I thought you might know someone. I’m going to let them know that this is something you would be better at doing. You do everything you can to make sure that something like that happens. That was the conversation. I just remember walking out of that room stunned. After all the things I’ve done and the people I’ve met, that still gets to me. It stayed on my mind for a year or two because they didn’t do anything and I was focused on what I was doing, but that conversation about creating Black superheroes always stayed in my mind.

Fast forward to 1991. I’m at San Diego Comic-Con and I literally sat up in bed at like seven o’clock in the morning. My partner looked at me, what’s going on? I said, I have to start a comic book company. She said, what do you mean? I said, I have to call my friends, I have this idea. What if we created a black comic book company? Not DC or Marvel, but we created these heroes. I had some rough ideas. I called Michael Davis cause he was at the con and I told him my crazy idea. Michael said, you’re nuts! You want to do a black comic book company with black characters? I said, yes, let’s meet. So we met and walked around the block and then we called Dwayne. Dwayne meets Michael and I and we literally walked around the convention center as I pitch this idea and Dwayne said, you are absolutely crazy – I’m in. So it was me, Dwayne and Michael walking around San Diego figuring out what Milestone was going to be. After that we figured we needed a business guy and the only business guy I knew was Derek Dingle, so we called Derek. We were all fans of Christopher Priest – Jim Owsley at the time. To me, Dwayne and Jim were the top writers. We called Jim who called us all crazy but said, I’m going to help you guys out cause you’re obviously are nuts and need some help. It was Priest who wrote the first bible that we sold to DC. Priest put that together. Dwayne came in afterwards and put together the huge Dakota Universe bible, but Christopher Priest back when we were spitballing ideas took it all down.

One of the things that struck me, then and now, was that Dakota is in the Midwest. I know tons of people of color who grew up and lived in Chicago and St Louis and Minneapolis and Pittsburgh and all over.

Dwayne’s from Detroit.

There we go. But it was very intentionally set in “the American heartland” and taking aim at the myth that it’s white.

Yes. That whole thing. Heartland. The heart of America. That’s why. When he first picked that, I was like, why not New York? But it wouldn’t have meant the same thing. Yes, placing it in the Midwest was a very deliberate choice. It came from Dwayne growing up in Detroit and being a Detroit native. Black people in the Midwest are different than the coasts because they have to deal with different stuff and that makes them unique. A lot of that informed our series.

Milestone had a lot of talented people and looking back now, you had an incredible lineup of talent who have gone on to do great things.

Part of why we did that was we couldn’t afford to get Walter [Simonson] and Neal [Adams], so we had to get new talent. [laughs] We were also uniquely set up to do that. Christopher Williams – CrissCross – walked into our office and he was awesome. We gave him Blood Syndicate. I remember when John Paul Leon came in. He was a student of Michael Davis. Michael doesn’t get any credit and he should because a lot of people came through his school – John Paul Leon, Shawn Martinborough, Felix Serrano. John Paul Leon showed up at the office with these Superman samples and they were incredible. I was looking at him like, dude, you’re like Alex Toth. He said, who’s Alex Toth? I thought, oh my god, you’re a genius, because you don’t even know what you’re doing and you’re doing it. Or where it comes from. I explained to him that the style he’s working in has a rich tradition and I showed him all this stuff and he just ran with it. He is better than I will ever be. John Paul is an incredible artist. Ivan was writing Blood Syndicate and bringing his own thing to it. Robert Washington Jr was writing Static. Everyone thinks Dwayne wrote Static. Dwayne edited it and oversaw everything but Robert Washington wrote Static. We worked with a number of talented writers and artists.

Ho Che Anderson wrote and drew a miniseries.

Ho Che did Wise Son. I was the biggest Ho Che Anderson fan. There were a lot of people in comics who worked with us who were slightly outside the mainstream, but we liked their vision and we loved their work. Ho Che was one of them. He reminded me of a radical Kyle Baker. I’m a big Ho Che Anderson fan. Moebius did a bunch of covers for us. Walt Simonson did a bunch of covers. Howard Chaykin. John Byrne. Jorge Zaffino. We worked with everyone.

You were working on it for longer, but Milestone was publishing for about five years?

About five years of continuous publishing by Milestone. We got hit with the implosion of the nineties. Some interesting decisions on our part at Milestone. There was a lot that led to its demise. Or, hiatus at the time. A lot of it was timing and the times. The comic book market was imploding so you couldn’t afford to make any mistakes. Any mistakes you made would be magnified and sales were declining anyway.

I’m sure even with DC’s backing, you didn’t have a ton of cash as a cushion for everything.

We had DC’s backing. Paul Levitz was incredible. Jeanette Kahn was always a dream to work with. There were people at DC who did not agree with anything we were trying to do. Outright racists saying, black people don’t buy comic books, black people shouldn’t be making comic books, we shouldn’t be trying to sell to black people anyway. We had to deal with a lot of that. That being said, DC up until a certain point were very supportive. It took a lot of guts for them to invest in this idea. They really wanted to do some good, I think. And we did. Hopefully we did. They backed us and I can’t say they didn’t support us, cause they really did.

At Milestone you drew Hardware for the first year and a half and then a lot of different things.

I drew Hardware for the first year and a half and then whatever I was called on to do. I designed all the costumes and all the characters and all that stuff for Blood Syndicate, for Static, for Hardware. I had to design the whole universe because we couldn’t hire anyone else to do it. [laughs] Dwayne and Priest had to write everything, I had to draw everything. But I drew Hardware for the first year and a half and then I handed it off for Wilfredo.

Then you drew the crossover, Long Hot Summer.

I drew Long Hot Summer and then Worlds Collide. Long Hot Summer was our first crossover event and this was at a time when crossovers were really hot. Right now as I’m talking to you, I am working on an Overstreet Price Guide cover featuring Static and Hardware. Full circle.

When was the last time you drew them?

The last time I drew Hardware was 2008 or 2009. Dwayne’s last story that he and I did for Milestone Forever. That was the last time I drew him in any official capacity. I drew Static for Edgardo Miranda-Rodriguez, who created La Borinqueña, the female Puerto Rican superhero. He asked special permission to team her up with characters from DC Comics so Static Shock teamed up with her and I drew three pages for this book with Edgardo.

The Liquid Swords cover happened while you were working on Milestone.

All this stuff happened in the nineties. Liquid Swords happened because Wu-Tang’s manager called me up. We were working on Milestone. Dwayne and I had just finished the designs for Mantis. They contacted me and asked if I wanted to do GZA’s album. I didn’t know who the GZA was at the time. I knew Wu-Tang, but I didn’t know GZA. I was a Public Enemy freak. Eric B. & Rakim fan. Wu-Tang was third on the list, but I loved the music. I worked closely with the GZA on the album cover. He would come up to my office and we would talk about what he wanted for the album, down to the inside sleeves with the characters fighting on motorbikes and the symbols and the different kinds of weapons they used. The interesting thing about the cover is that if you look at it, a lot of that is done in pen and a lot of that work on the inside was done as sketches I made to show him what I wanted to do. He looked at the sketches and said, why don’t we just use these? I said, because you can still see the construction lines, you can see where I X’ed something out cause I didn’t like it. He said, let’s go with it, it’s dope. So except for the cover, all the art in that is sketches I had done to show him. Including the back cover where characters have the long sleeved Wu-Tang shirts. Those were all done as rough sketches. To this day I’m still embarrassed that people look at that. [laughs] It was never intended for people to see. But that’s what he wanted. And he was right. It was a good move.

The cover remains gorgeous.

You’re so nice. I look at the cover and I see all the things that I should have done differently. I got a chance to fix it because Marvel Comics commissioned me twenty years later to do a hip hop tribute to the Liquid Swords cover so I got to do Iron Man and one of his villains in that pose – and I got to fix all the things I did wrong in the original one. [laughs] I think Bill inked the second one.

Did you ink the album cover?

No, Prentice Rollins inked the album cover. I think it was Prentice.

Clearly even after Milestone ended you had a good relationship with DC.

Thankfully I had a really good relationship with DC and Paul and everyone else. It was rough. They probably didn’t like a lot of the things that I did, but they never abandoned me. They were always wonderful with me.

You spent over five years working on, I don’t make it sound utopian, but it was your dream project and you brought it into the world – and what do you do after that?

What do you do after that? I mean in my case, I went and worked for Motown. I worked with Michael Davis at Motown, putting together a comic book line and made characters for them. I went from New York to California and then I started working on storyboards and animation design and storyboard work. I worked with Dreamworks and Harve Bennett’s company for Invasion America. Did a ton of different stuff. Then I got a call from Alan Burnett. I was redrawing the Hamburglar on tiny panels to make the model accurate. That was my job. I was The Question artist and that’s what I was doing then. [laughs] I got a call from Alan and said, I just finished a meeting at Warner Brothers and I pitched them Static with one line. They want to do it and they want to meet you. I said, what? What did you tell them? He said, I told them, Chris Rock at 14 with superpowers. They were like, we’re in. So I went in and told them what the show was about, without realizing that’s what I was doing. At the end of my little speech, they bought the show. So I’m working on Milestone again, but this time I’m in California directing a TV show and designing a TV show starring our characters. Milestone was over in terms of the comics, but not in terms of the property. At all.

Right before then you and Priest worked together.

We did Steel for DC. After Milestone and after all that happened, they asked me to do Steel, which I thought was ironies on top of ironies. I’m drawing a character that to me was probably inspired by what Dwayne and I had done on Deathlok and what we had done with Hardware. I’m working on Steel! With one of the Milestone guys! It was bizarre. I had a lot of fun on that series, though. I liked working with Christopher Priest. Him and Dwayne at that time were my top dudes to work with in terms of writers who I felt very sympathetic with. Not a lot of conversation took place for me to get to the essence of what they were writing and to be able to translate it. In a way it was a mini Milestone with Steel. Except it was never quite like that because it was a DC character, but I felt like I had a lot to do with his creation. [laughs]

Besides the Milestone development process, had you two worked together before that?

No. Prior to that, no. I’d always see him at Marvel. He was working with Larry. He had the cleanest, dopest office at Marvel. I would always see him and talk with him but we never worked together until Milestone and it was love at first sight because he was awesome. Still is.

After Static Shock you and Dwayne kept working in animation.

Yeah, we just didn’t do it together. We were working on other stuff. I started working at BET and I brought Dwayne in to work with me on some projects there, so we got to work together again. When Dwayne got to Hollywood he immediately became very successful very quickly because people realized how great he was. I don’t know how many scripts he had written up to that point, but I don’t think many. He was always just a great writer.

You two would come back and do comics from time to time.

Occasionally we come and grace comics with our presence. [laughs] It was more like, we needed money.

What was Dwayne like as an editor?

I worked with him every day for years. We were always at each other’s houses working on stuff. Dwayne was casually brilliant. Every room he was in, he was usually the smartest guy in the room. He was constantly amazing. To be around him was something else. It wasn’t like he sat around saying brilliant things. He was low key about what he did. He was so sharp and so right about his approach to things. You’d have to ask a writer what it was like to work with him as a writer. I can tell you what it was like working with him as a partner and an artist. It was always thrilling. He was always willing to incorporate your ideas – if they did not suck. [laughs] Him and I truly collaborated. It wasn’t like he wrote scripts and I drew. It was really a back and forth. He was one of the most talented people I’ve ever had the privilege of knowing. Maybe the most. If he felt right about something, he could be stubborn. He could be curmudgeonly in that it wasn’t easy to satisfy him all the time and he could be a miserable dude at times. Which was fine, because we were all under such strain. It’s amazing all of us got along as well as we did. Being at Milestone was like being in a band. We broke up after five years because the internal pressure spending 24 hours 7 days a week is intense. Then you have financial problems, family stuff, books you’ve got to get out, talent you have to deal with, rents you have to pay. It was a lot. Somehow Dwayne and I managed to make it through all that. In the end, Milestone went away, but we reconstituted ourselves and ended up working together again at Warner Brothers. And it was the same kind of collaboration.

We just understood each other on a creative level very intuitively. Anytime we had to make something up or come up with a script idea we would sit in a room and look at each other and just start talking. He would say a sentence and I would say a sentence and then he would add on to that and we would build on each other riffing back and forth. He was quick to discard any idea that sucked and I was quick to not like some stuff just because. That’s the way we did Milestone and that’s the way we did all that stuff. The last time we collaborated I was up at BET and Dwayne was writing some stuff for DC and he was in my office and we had to come up with a property for BET. I wish we would have have done it. Thinking about it, we should have done it. We sat in my office, looked at each other – just like we had done all those years ago – and started talking. An example would be, he’s a black guy about 35. I’d say, he’s an ex-athlete. Dwayne would say, he was a baseball player, but he had an issue. I would say, he’s retired and he never got along with management because of his attitude. Dwayne would say, but with his superior hand-eye coordination and his brain, he has to do something. What is he going to do with this talent? Okay, he’s going to open up a detective agency. But with who? Or, he’s a boxer for hire. Except, he’s blind. We would keep riffing like that until at the end of an hour we had an outline of what we wanted to do. Thinking about it now, it was really cool. That was how we did everything. Sentence by sentence, back and forth. Then he would go and write it and I would go and draw it. Or we would hand it to someone else to write and draw.

Wow. Working like that for years, that sets a high bar for every other collaboration.

Yeah, it does. Reggie [Hudlin] and I will riff of each other about ideas, but other than Reggie, Dwayne was the guy. He was amazing. He was truly great. I wish he was still here to see what the world became. He wasn’t able to a part of it.

One of the more recent comics projects that really stands out was Black Panther/Captain America.

That was with Reggie.

It stood out for many reasons. Including you returning to Marvel. How did it happen?

It stood out for many reasons. Including you returning to Marvel. How did it happen?

Reggie was writing Black Panther at Marvel and he and Axel Alonso, who was the Editor in Chief at Marvel at the time, cooked up this idea of a Black Panther/Captain America miniseries and they approached me to do it. I had known Reggie for years but I think that was our first project. Axel and Reggie called me in. We discussed the story a bit before I got a script. I had some input, a couple suggestions, but they had fleshed most of it out before it got to me. The first two issues of the miniseries were inked by Klaus Janson and I think the second two were done by Tom Palmer. So I had the very very best for all four issues.

I said that before, Hardware #1 summed up why you and Dwayne left Marvel. I think you laughed at that.

[laughs] I don’t know if we consciously did it like that. We probably did. I’m just thinking about what the people at Marvel must have thought. We did Deathlok and then the first thing we come out with is Hardware and angry black man! They must have been thinking, what did we escape? [laughs] That’s why I’m laughing.

To be fair, some probably would have thought that regardless of what you made.

Yeah, dodged that bullet.

Did you have any hesitation about going back to Marvel after that?

No. None at all. One of the things that I’ve always wanted to do – and what I’ve managed to do – from early on, is always work with the very best people you can work with. Starting out, I worked with the best guys in comics. Denny O’Neill. Bruce Jones. Sam Hamm. Dwayne McDuffie. All the very best people. Reggie is one of those people. He’s not only a top filmmaker, but he’s one of the top writers in comics. I had no hesitation at all. It was like collaborating with Dwayne. An old friend whose work I understood just by looking at it.

Not long after that you did Dominique Laveau.

Not long after that you did Dominique Laveau.

That was a trip.

Clearly you got the bug to do more comics again.

The desire to make a living had something to do with it, also. [laughs] I really wanted to get into it – and I really have to have money to spend. You go back to the stuff that you love and that pays you. We did Dominique Laveau for Karen Berger over at Vertigo. It was an interesting book. I thought it had a lot of potential. I still think it does. It was a very weird, excellent series. Somebody should take a look at that and adapt this story about the descendent of the voodoo queen of New Orleans. Unfortunately I don’t think it ever gained traction with people. No one knew it existed outside of a very select hardcore group of Vertigo people. There were a number of issues with that book. There are a number of things I would do differently now if I had to do it again. Looking back, I think we should have colored it differently. But working with Selwyn Hinds, he’s a great writer.

Your art was a little different for the book.

It was different. It was also a genre where I don’t do a lot – mystic horror steeped in voodoo rituals – so I had to stretch a bit. I’m proud of a lot of things we did on that book. I just wish more people had seen it.

You were trying to evoke mood and shape but then also do this very detailed ornate representation of place and New Orleans.

You’re amazing cause you’re the first person to ever ask me about that series. [laughs] Aside from that time before we talked. I’m glad you dug it. You and maybe one other person. [laughs]

On the very different end of things, you drew Black Lightning/Hong Hong Phooey. How the heck did that happen?

[laughs] Dan Didio asked me out to lunch. I wasn’t going to turn that down. I met him at his office and we walked to a place in Burbank. We started talking and Dan can talk a mile a minute. He has all these ideas and most of them are interesting. Any conversation with him is informative. I remember thinking, I’m sitting here with the publisher of DC Comics – what do we have to talk about? Well, it turned out we had a lot to talk about. We talked through the usual b.s. stuff and then we got to it. He said, I want you do a Black Lightning/Hong Kong Phooey story. I just looked at him for a long time and said, I’m not doing that. I don’t like Black Lightning and I don’t like Hong Kong Phooey. I mean, it’s not like I don’t like them, but I don’t have any connection to them. I looked at him and said, you’re asking the guy who invented Static Shock to draw Black Lightning and a dog? If you said, Static Shock and Hong Kong Phooey, I might do that. We talked for a while and I eventually agreed to do it. He didn’t browbeat me into it. Like I said, I have to make a living. It was a very interesting conversation with him trying to convince me that this was the way to go. Down to what the cover would look like. He had a very specific vision of how he saw it. My personal challenge was to take two characters that I didn’t have a connection with and have a connection with them in order to do it. It was all entrenched in the seventies and blaxploitation and Hong Kong movies. It turned out to be a lot of fun. He asked to do it and I couldn’t think who would even want to see that. It turns out it was pretty successful.

I think most people’s response to the book was, what?!

Yeah, but sometimes that makes you pick the book up. Like Batman and Elmer J. Fudd. I need to see what this is because it’s so ridiculous. And that was a brilliant book by Lee Weeks.

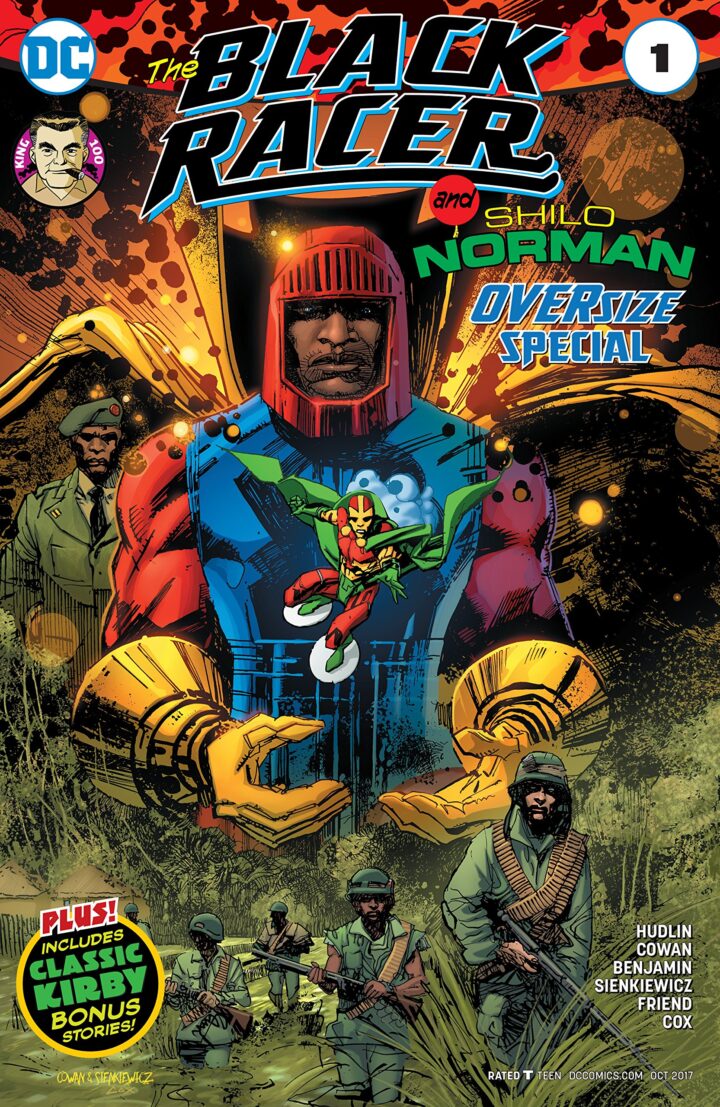

You also drew a Black Racer/Shilo Norman book.

Yeah, I became an expert at doing these giant one shots. That came about because the editor Jim Chadwick was putting together this Kirby tribute book and asked me if I wanted to contribute to the book. I was at the DC office with Reggie at the time. I stopped and Jim asked, want to do this? What character do you want to do? I asked, did anybody take the Black Racer? I want the Black Racer. That’s the only New Gods character I ever really wanted to draw. Reggie joined us in the office and I pointed at him and said, he’s writing it. Reggie said, I’m writing what? I said, Black Racer and Mister Miracle and Reggie said, okay. That’s how casual it was. We discussed that story and he went and wrote it and then I drew it. It was a great time. It was the Black Racer, who I always thought was the coolest character. A black man on skis. It was awesome. Then I found out how difficult he was to draw. How to make sure that helmet looks okay. How to make those poses look cool and majestic. And all you’re looking at for reference is Kirby art so you’re already intimidated. [laughs]

He’s like the Silver Surfer where he seems simple.

Yeah, but he’s not easy. It’s not easy drawing someone skiing through space. I mean it’s probably not easy drawing someone skiing on snow. It was fun.

Why do you like the Black Racer?

He was black. I always thought the way he was depicted was cool. He was a paraplegic vet who got these powers and had all these powers only to return to bed and nobody knew except him. The concept was the best shit ever. Plus like I said, he was one of Kirby’s few black characters. I had done the others like Black Panther already. It was time to tackle another one. And if he had another one, I would do that. I love Kirby characters and I love black characters.

And now you’re drawing The Question again.

Talk about full circle! Dan Didio and Jeff Lemire approached me about doing it. I was interested but the right storyline had never presented itself and Jeff Lemire had a very interesting take. He called me up and we hashed out a story, we pitched it to Dan. Then we retooled it and Dan liked it and that’s the story you see now. Jeff Lemire is an incredible writer. I am so grateful to be working with him. But again, I’ve worked with literally the best. Working on The Question this time is different cause I don’t have Denny getting on me about everything. [laughs] But it’s good.

Do you mail him the issues?

I should, just so he can get on me about them. [laughs] I can feel, okay, now I’m really doing The Question. [laughs] No, I don’t. I don’t want to bother Denny.

You and Bill have worked together for a while now. You’ve worked with a number of inkers over the years, what do you like about working with Bill?

Bill has the unique ability – Kent Williams can do this, too – to pull the essence of whatever I was trying to do out of the work, identify, and amplify that. What Bill can do is look at what I did and see my intent. Even if the lines aren't perfect, he can get my intent and carry it across the finish line. It’s very rarely not what I wanted. Or a better version of what I did. That’s what Bill brings. He can capture the essence of what I do so well. He’s an incredible draftsman. He’s one of the few geniuses this field has produced. Let me put it this way, I’m very lucky to be working with him. Very lucky. Because this work is extraordinary. I think we make a very good team, but a lot of that is due to the excellent work he does. As amazed as people are when they see the art, when I first see it, I’m the same way. I’m the same way. Sometimes it’s so good and it’s only after I see what he did that I get it and see how brilliant it is.

Do you still draw on paper?

I’m working on paper as we speak. I still work traditional on paper. I haven’t mastered the computer so that I can do it fast enough. It takes me more time to do that than it does to just draw the damn thing. Very old school.

At this point is some of that just ease and comfort? Knowing your materials, how the paper absorbs it, all that stuff.

All that stuff. And I don’t have those sharp computer skills. Bill does. He does a lot of stuff on computer. He’s always been like that. That being said, I have all that equipment. I’ve done that. It just takes me way too long to do that consistently. It’s easier to just draw it, which I know is weird in this day and age.

Time is of the essence.

Time is of the essence on all this stuff. Bill is inking this stuff twice up. He’s taking these large pages, blowing them up more and inking that. There’s a ton of stuff that fans are not aware of, but we are not doing this book on computer.

What size do you guys work at?

I’m working on 11”x17”. But the original sizes for these books are 15”x23”. The pages are huge. Bill is inking pages that big.

Do you like that size?

I don’t mind working at that size. I’m not drawing a lot at that size. Bill is inking a lot of stuff at that size. It’s okay. I don’t feel like I can suddenly express myself as an artist now that it’s this big. It’s just the format. We’re professionals. I’m not getting too caught up in my artistic preferences. It’s about what the job needs.

Part Two:

Cowan and I spoke early in the year and then we spoke more recently after the return of Milestone was announced at the DC FanDome online event. He had talked about working on Milestone, but was unable to say anything about it earlier, and I asked if we could have a short conversation to talk more about the revival and other topics.

I know plenty has happened since we spoke, but Denny O’Neill passed away. I know we joked about how you should send him the new Question series so he could brutally critique it.

Yeah. Now it’s too late to do that. But yes, he passed away and it put a different slant on some of the things we talked about.

You said how as a writer and editor he kicked your ass.

That’s accurate. He did kick my ass. To the point where when I saw him again I still had PTSD. [laughs] When we finally connected, it was awesome. He didn’t seem to have any memory of torturing me. I got over it. It was all love.

Did he just torture everyone?

I think he held out a special thing for me cause I was a young. Thinking about it now, I don’t know how he dealt with me. I was just a young 20-something year old kid who had all the answers. I have a twenty-seven year son now and he has all the answers, so I can only imagine how I was at that age! Poor Denny had to deal with all of that. I probably owed him an apology more than anything.

So, Milestone is back. All the legal issues have been settled, I take it?

Without getting into the weeds too much, all the legal stuff that had been going on between Milestone and Dwayne McDuffie’s widow has been resolved. There are no issues. There’s no ill will towards anybody.

Are you picking up from where the books ended, or years later, or starting from scratch, or what are you planning?

We’re picking up from the old books. There are some new stories. Some of the characters have been revamped slightly, but it’s still all the characters that you love. The thing with Milestone – Reggie said it and Dwayne said it and it was true then and I think it’s still true today – is that we do the stories that no one else can do. That no one else would even try to do. Even in this day and age. Be prepared when this comes out to see some stuff you’re not ready for because even in 2013 and beyond we’re working on stuff that we think will blow people’s minds. Stuff that made DC Comics nervous. Which means, you are on the right path. If it makes them nervous, then it’s probably something you should do. So there’s quite a bit of that.

One of the big projects is a Static Shock graphic novel by Reggie Hudlin and Kyle Baker.

A lot of that is done. Kyle and Reggie started collaborating a couple years on it. We think Kyle is a genius walking among us. He’s one of the greatest artists, storytellers, humorists, writers who’s ever done comics. To get him to do something with us was a major get and a major source of happiness for us. And that graphic novel is something else. If people go on Kyle Baker’s twitter feed, he’s put up a bunch of images from that.

The announcement pointed to the difference between now and the nineties. Back then you launched Milestone with four monthly books that eventually led into a crossover and spun out titles from there. Today it’s a monthly print comic and a digital monthly comic and a graphic novel and multimedia plans.

It’s a whole different world and whole different way of doing stuff. A whole different way of publishing and the way people get information. Readers aren’t consuming books in the same way they did back then. I’ve heard from comic store owners and other people complaining about the digital first books and about how it’s easier to pirate, how it doesn’t help them, and other issues. There’s a lot to that. But it’s about reaching people. How do they consume things? If they’re not reading print or going to a store to pick them up, well, you can print anything you want cause no one’s there to buy them. What are you going to do then? A lot of kids don’t read comic books that way.You have to figure out ways to reach them. You’ve got to go where people are. Simple as that. Publishing has changed because society and technology and everything has changed. When we launched we did those four titles so we would have one book a week. Now that’s meaningless.

Greg Pak is co-writing Milestone Returns #0. Can you say anything about what he’s writing?

Greg was one of the writers that we wanted to work with for a long time. Reggie is especially a huge fan of Greg. He’s working on a new Milestone project that has been yet unannounced but if you look at the post I drew, you’ll get a hint at the characters.

I came across a photo from a 2017 Milestone panel and one of the people there was the novelist and writer Alice Randall. Is she involved?

Alice is a friend of Reggie’s and a friend of mine. A very prolific writer, a black country songwriter, and a professor. Back when we were first going to start Milestone back up she wrote some excellent treatments for us. Hopefully we’ll get to work with her in the future because she’s fabulous.

So you have a lot more plans than just what’s been announced.

What people see in the zero issue is just the tip of the iceberg. There’s a ton of work already done. There’s a lot coming down the pipe.

One of the things announced was new ongoing series Icon and Rocket that you’re drawing. Talk about designing Icon back then and rethinking him today.

In the early days, after we created the characters together my task was to design these characters. I think Icon was one of the last ones that I did. I knew he had to be a Superman-type. It had to be a reinterpretation of what kind of costume a person like that would choose for himself. Or what kind of costume Rocket would choose for him to wear. So we went with red black and green. Kind of like an African influenced Black American answer to Superman’s costume. People said, you need to have a cape, all superheroes have capes. For Rocket I had to figure out what a teenage girl would want to put on in 1992. I remember at that time TLC and a lot of girl groups like that were big and so I modeled her after a combination of TLC and Halle Berry.

So fast forward to 2016 or whenever. We did a bunch of redesigns and we gave Icon and Rocket to Ken Lashley to draw. Ken really wanted to do it and we really wanted him to do it. One of the first things he started doing was Icon and Rocket redesigns and they were brilliant. I really like Ken’s stuff and I liked what he did. The new version that you see is Ken Lashley’s redesign. The costume is now red and black. The costume may be revised as we go, but it’s really a Ken Lashley redesign. What Ken did was he added an “I” to the chest so you can have that symbol. Like the S for Superman or the bat for Batman.

You haven’t really drawn Icon before this.

I talked about this a little during the DC FanDome. The truth of the matter is I’ve never really drawn Icon. I designed Icon and Rocket. I did the turnarounds for the characters – showing them from different angles. I drew the first two covers. And then I don’t recall drawing him again really until 2016 or 17. I found myself going in like, I am Milestone, I know these characters, I made them up – but I didn’t have a clue how to draw them or what to do next. It was really an experience. I had to go and look at what Mark Bright and Ken Lashley did to figure out what I was going to do with the characters.

Titling the new series Icon and Rocket is very intentional and the original series was very much about both of them.

It was. That whole book was really a black teenage girl’s book disguised as a superhero comic book. All the stories were told from her point of view. She was the major voice in the comic book. You saw how she was thinking and saw how she reacted and saw it from her perspective. You can correct me if I’m wrong, but Icon didn’t have any thought balloons. We never heard a story from his point of view. We heard what he had to say about it, but we never knew what he was thinking. We always knew what she was thinking. Dwayne and I cracked up a little bit saying, we’re putting one over on people, we’re getting them to read a girl’s book. [laughs] It was fun to do. But that was Dwayne’s genius. He could always do stuff like that.

Is that how you and Reggie are approaching the new series?

The same thing. The same point of view. Reggie is a great writer in his own right and he has his own spin. Icon and Rocket was his favorite series of all the Milestone stuff. There’s some great stuff including an updating of Icon’s origin story and the consequences of what happened back then. It’s really compelling what Reggie did and a lot of fun to draw.

I don’t think anyone knew what to make of characters like Icon and Rocket back in the day.

[laughs] Good! I think that’s good. It may have been your cup of tea or it may not have been your cup of tea, but no one gets anywhere doing the same thing everyone else does. If it came out today, it would still be shocking. There are parts of Static or Blood Syndicate or Hardware that if they came out today people would be like, are they really doing this? So in the spirit of that, you can only imagine what we’re planning. [laughs]

It’s been interesting to talk with people over the past few years about diversity and characters and how those conversations have shifted over the past few years.

I don’t know. Since we did Milestone in 1992, or however long it’s been, I’ve seen some change in comics, but let’s be really real – what have you seen since Milestone that has been that different on that level? Nothing. We’ve seen individual books like Black, Excellence, Bitter Root. They’re great, but they’re sporadic. I don’t think the industry has been open to anything like what we did. The industry has settled back into the storylines of the month and variant covers of the year and all these things that have nothing to do with content. The elevation of the writer as the sole creator of comics. Everyone else is an afterthought. Nothing in terms of race improvement. The situation of people of color in comics, addressing any kind of sexual or racial imbalance in comics, all of those things are being talked about now – but they’ve been talked about in the last two months not the last twenty years. Not to the extent that you would think. So there may be change. I didn’t see a lot of it, but I’m starting to see it now. It took a guy being murdered for that to happen. That’s what I’ve observed. So we’ll see how companies really react. The real change isn’t going to be some black books or hiring a few more black writers or artists, it’s systematic change. We need everything from the top down, from executives to editors to all the people behind the scenes. DC is better at this than a lot of people but there’s still a lot to be done. You’ll see change when that starts happening. It goes beyond just hiring some black writers like David Walker and Reggie Hudlin and all these cats. It’s got to go beyond that.

It has go beyond individual books and individual creators. You mentioned Bitter Root, which is one of the best comics out there right now, but how many Black creators, or just non-white creators, has Image published in the past decade? And supported? Not to single them out, but it’s not great.

It’s not great. Let’s talk about how many black editors there are in comics. That’s even less impressive.

And those two facts are related.

Yes. There’s a lot of work to be done. And I’ve pointed some of these eatings out. I’ve been pretty vocal. I didn’t have the power to make them do anything. Every time you go up to a place and all you see are white people and very few women but a lot of white dudes and their friends. Not reflecting the real world at all, but a fanboy version of it.

I still come back to Blood Syndicate, which may be my favorite Milestone comic, but it was as deep and multicultural a book as has ever been made in comics. To this day.

I still come back to Blood Syndicate, which may be my favorite Milestone comic, but it was as deep and multicultural a book as has ever been made in comics. To this day.

That book had gay characters, Black characters, Latino characters, Asian characters. It was a book featuring street gangs, but it was really about family. The family you have outside your family. The tribe where you belong. Ivan Velez wrote it and he put everything he wanted to put in that book. I’m sure he’d disagree and say they stopped me from doing everything, but we really enjoyed what he brought to that book and what he wanted to do. Blood Syndicate was tricky because people got freaked out about the name. And even today – if theoretically we were talking about Blood Syndicate – people get freaky. [laughs] I’m serious, they get kind of nervous. But to me, that means it’s the one you should do. If it makes people nervous, that’s the one you should do. It means you feel something about it.

Before, I could this excitement in your voice as you were trying to not say anything. I know the next big thing is always exciting, but you’re clearly excited about this.

I am very excited. It’s the new thing and it’s the old thing. I was excited before when I couldn’t really talk about it and I’m excited now, but I have to also say that it’s not the easiest thing to maintain that kind of enthusiasm. It’s been six years of maintaining enthusiasm against crushing disappointments all the time. Now its enthusiasm mixed with a bit of, “is this real?” [laughs] But that’s the business we’ve picked. I’m very excited about Milestone and what we’re doing. And while I’m not thirty anymore like when we first started, all the societal issues that made us start this company in the first place are still happening. So I’m excited because I think that it’s fortunate in a way that we had a delay of all those years because things come out when they’re supposed to come out. I think the Milestone books will come out at a time when they’re needed and when they’re supposed to be. My voice is enthusiastic mixed with disappointment mixed with getting the energy to really deliver it again.

I said it before, but I’m not sure what people are going to make of some of these characters and books. I’m not sure that people got them back then.

They didn’t! I know that. [laughs] The first words in Hardware were “angry black man.” That was the title of the book! How would that go over today? I don’t know. You tell me. Just as many people would be as upset as they were back then. We’ll see, won’t we? We’ll see soon if people think it’s controversial. I think it is. Cause if they’re safe comics, then we’re not doing anything right. We can’t make the same comics everyone reads. We have to go beyond that. Way beyond that. I think we have.

So many revivals now are brought back because they’re familiar, to be comfort food, and you’re very much taking the attitude that this wasn’t comforting then and you won’t start now.

You can quote me on that! We were never comforting. And we’re not comforting now. Entertaining, yes. But comfort, where you read a superhero comic and feel good about society – no. That is not what we do.

There’s a range of human experiences that we as readers can experience through reading comics. I learned all kinds of stuff as a kid reading comic books. Some were bad. Some were life lessons. I read stuff that expanded my consciousness and made me question things. Some were just entertainment. I think comic books can do all of that. Alex, I think even thirty years ago at Milestone we had already added to what comics can do and what they could be. What the power of comic books and the power of that visual storytelling that we do can be. I’ve always felt that way. I want to keep doing that.