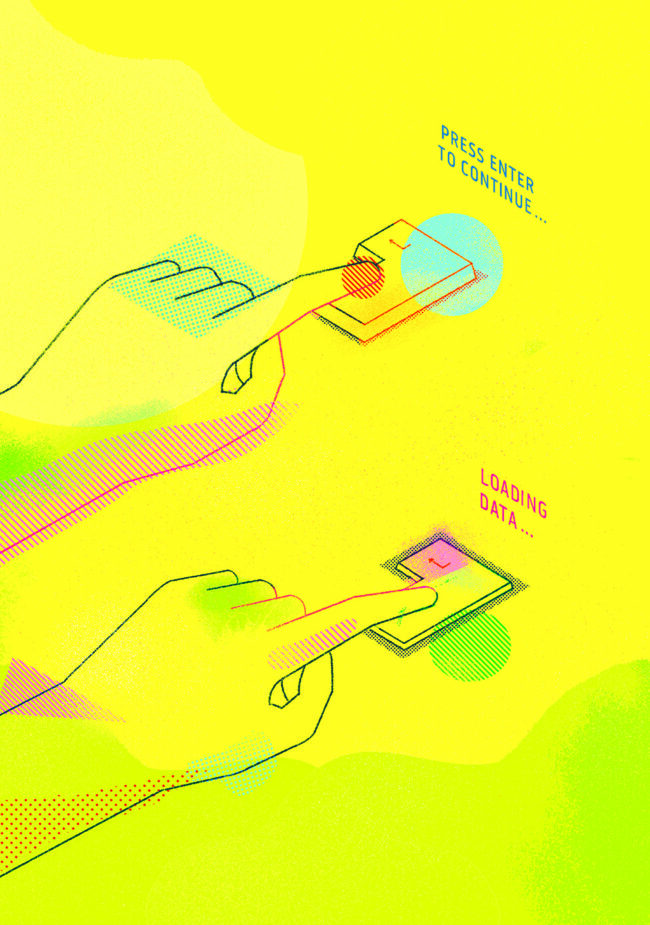

Thanks to the English translation of her book Press Enter to Continue being published by Fantagraphics in 2019, and the subsequent Ignatz nomination, it can be said that Ana Galvañ is one of the most prominent names from the new wave of Spanish comics artists in Anglophone comics.

Thanks to the English translation of her book Press Enter to Continue being published by Fantagraphics in 2019, and the subsequent Ignatz nomination, it can be said that Ana Galvañ is one of the most prominent names from the new wave of Spanish comics artists in Anglophone comics.

Galvañ was featured in the Spanish Fever anthology back in 2016. In the intervening years, her style has developed from a painterly and somewhat folksy style to the more radically digital and geometric one she is currently employing, one which draws significantly from the Constructivist movement. The Spanish scene in general has also changed quite a bit, mostly in terms of who’s making comics. While Spanish Fever showed a scene dominated by men, the rising tide boasts far more women, whose work is interested in topics as diverse as contemporary social pressures, manga, punk, sex, and feminism, and often the intersection between all of them.

Press Enter’s diegesis is composed of ambiguous places and impressionistic stamps of color. Galvañ’s characters seem somewhat detached and robotic, attempting to navigate a world that has similar elements to the reader’s, but that exist in some fantastical parallel universe. A braver critic than I would maybe talk about how her work depicts something akin to the posthuman or the cyborg, due to the fact that it’s human-shaped characters appear enmeshed and fully “plugged in” to the digital technologies that surround them. It can be characterized as an elliptical story, one well suited for somewhat elliptical times.

If Galvañ’s art looks familiar but you’ve never picked up one of her books, it’s maybe because you’ve spotted her work in The New Yorker or The New York Times, or one of the innumerable periodicals that have commissioned her. Or maybe in one of the commercial ad campaigns she’s worked on. (Like many illustrators, she has an advertising agency background.)

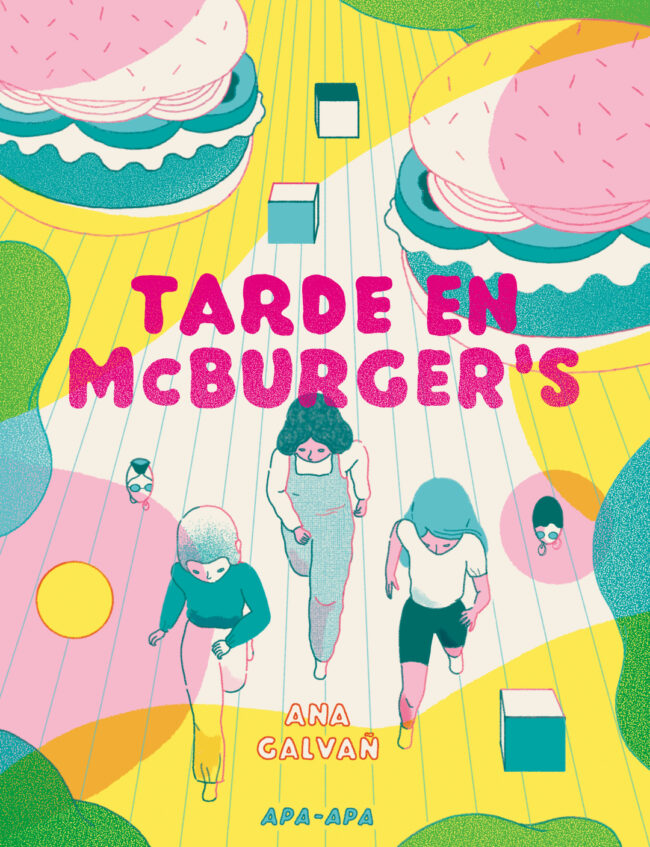

Seeing as Barcelona’s Apa Apa published her latest book, Tarde en McBurger's [Afternoon in McBurger’s], in 2020 (due to come out in English via Fantagraphics in the near future), we thought it was high time to talk to Galvañ about her influences and approach.

This conversation took place in Spanish via email in the last half of 2020. Questions and introduction text by Nicholas Burman. Questions and translation by Isabel Palomar.

Nicholas Burman & Isabel Palomar: The most obvious thing to say about your work is that it's very design-influenced. Could you say a little bit about your educational and professional background, and the sort of influences from outside of comics that have influenced your work?

Ana Galvañ: I studied Fine Arts and specialised in graphic design, and my first contact with graphic arts was the Bauhaus and Russian Constructivism, influences that have always remained important to my work. While I was studying at university I also became very interested in avant-garde art from the beginning of the 20th century. After university I worked as a designer and later on as an art director in advertising agencies.

Growing up, were you reading a lot of comics, or did that come later? When did the need to tell a story overcome the want to make isolated images?

I started reading comics and watching anime as a kid. I grew up reading Mort & Phil, Asterix, and Tintin, among others. I continued reading manga and watching anime, such as Robotech, Ulysses 31, and Dragon Ball. I think all of them influenced me in one way or another.

What tools do you use - is pen and paper involved or are you mostly utilizing digital tools?

I always start by scripting my comics; that’s what I most enjoy doing. I find it harder to reflect my ideas in everything that comes after that.

I use digital tools, but my working process is similar to a manual one. I use a graphic pencil and a tablet. I start sketching with a digital pencil, and then I ink, colour, and add shade to my illustrations.

I wanted to touch on the influence of Constructivism in your comics. Geometric shapes and block colors are very prominent. Do you think this style has driven the sort of stories you tell, or vice versa?

As I always start by making the script, I think I adapt my graphic style to the story as much as I can, but I don’t think that what I want to tell is influenced by the style. If I need to change my approach in order to do it, I will do it.

Two other striking aspects of your comics is your use of color and your deconstruction of the page layout. Your pages often feature these interruptions of colors that look like they come from an analog printing process. Do you have a particular idea in mind when you employ this type of coloring?

I try to use color as another narrative element in order to highlight key elements and also to reflect emotions.

You use very geometric shapes for "stuff" and then flowing lines for animals and humans, is creating that distinction important for your world building?

Yes, the contrast between the organic and the geometric is a very important and necessary element to me. I think that otherwise it wouldn’t work as well as I would like.

You were recently nominated for an Ignatz Award, in the Outstanding Artist category. Is that the first time you’ve been nominated for an Ignatz? Are there other nominees from this year’s shortlists whose work you’ve been enjoying yourself?

It made me very excited because prior to that I wasn’t sure how popular my book Press Enter to Continue was in English speaking countries, specifically in the USA. I thought it would have gone more unnoticed.

I especially like the work of Michael Deforge, Eleanor Davis, Gabriel Bell and Tommi Musturi, although there are still many authors that I don’t know about, but I’m sure they’ll be great to discover. I’m still investigating!

Let’s talk about your latest book, Tarde en McBurger's. It’s being published by Apa Apa, who also published the original Spanish version of Press Enter. How is it working with them?

I had an idea to make a zine that would be published by Apa Apa and present it at Barcelona’s GRAF festival. Eventually the story ended up being longer than I expected, and I suggested to editor Toni Mascaró that we could publish something longer, around 40 pages or so. However, when he saw the draft, he liked it so much that he suggested that it could be a 64 page book instead of a stapled zine.

When did you start Tarde en McBurger's, how was writing and drawing this book different from Press Enter?

Tarde en McBurger’s could have actually been part of Press Enter because it’s coherent with its theme and graphic style. The main difference was my intention to go deeper into the psychology of the characters.

It has been very nice because the editors (Toni Mascaró and Seri Puyol) and I understand each other very well. I think that we all have a very open mind, and this allows us to understand that a comic is a medium that involves different languages and very intimate approaches that go beyond the classical western narrative form; a form that some conservative sectors seem to want to impose as a universal language.

Readers can expect an intense and emotional story, narrated in a synthetic and non-linear way, which plays with some temporal parodies. The book is being translated and edited into English. Thanks to the mediation of my agent Alessandra Sternfeld and Apa Apa, it will be published soon in the United States by Fantagraphics.

Has Press Enter been translated into other languages, too? How do you feel about your work being translated, do you feel like you lose some control over it as the language changes, or is that a process you enjoy?

Press Enter has only been translated into English; the French rights were sold but it never ended up being published there. The English translation was done by Jamie Richards, who kept in touch with me during the whole process. When she was done, I was sent the final translation to revise it and I thought it was a good representation of the original version and that the comic didn’t lose anything.

Regarding the neutral language in your comics, it feels like you purposefully make your characters somewhat robotic, which is fitting given that your stories also tackle digital culture and automation. How and why did you decide on this “neutral" voice for your characters?

I don’t see any way to approach these characters and this narrative other than with this sort of frigidity. I have struggled drawing characters smiling or expressing any other kinds of emotion ever since I started drawing. I guess it’s a matter of shape and style because my narration is also synthetic and schematic. That’s why I use other resources, like colour, to communicate emotions and feelings.

Your books have very vivid colors. Are you deeply involved in the printing process, choosing inks, paper stock, etc.?

When I edit zines, yes, I am. I love deciding on the kind of paper and the color of the inks. The touch, the smells… it’s almost a fetish. However, when I publish with Apa Apa, they are in charge of choosing that stuff, and as they are very careful and authentic professionals, the end result is always delicious.

You were featured in Spanish Fever, published in English in 2016. How is the Spanish comics scene now? Are there new artists you’re enjoying?

I think that Spanish Fever is a good anthology despite not featuring the talented work of the emerging and mid-career artists that represent the more original and creative comics right now. Here are some of them (I am aware that I am leaving many out of the picture): María Medem, Roberto Massó, Andrés Magán, Míriampersand, Conxita Herrero, Begoña García-Alén, Roberta Vázquez, Carla Berrocal, Marc Torices, Pepa Prieto Puy, and Genie Espinosa.

You’ve contributed to Genie Espinosa’s all-female Raras fanzine, how did you get involved in that?

You’ve contributed to Genie Espinosa’s all-female Raras fanzine, how did you get involved in that?

It was fun and exciting to participate in Raras for two reasons: the first one being that I love participating in zines and collective projects, and the second one being that I enjoy being surrounded by female authors and illustrators with whom I think I have a lot in common.

What do you think you and these other rising cartoonists in Spain, also in Raras, have in common? What’s the common thread between your interests and your work?

I think that we belong to a new generation of female authors that has gained more visibility, and have achieved changing the rules in what has traditionally been considered a male profession. For instance, we no longer need powerful men in key positions to be able to prosper in our careers. We don’t owe anything to anyone, it is down to our great efforts and persistence. In general, we are sure that we are stronger together than individually, and despite being very different, we support the collective.