English-language editions are still the Holy Grail for European comic book authors. As the world’s lingua franca, an English translation is the doorway to expanding your readership around the world. However, the expense and risk associated with producing translations has meant, until very recently, that very few publishing houses have taken the step, much to the frustration of European authors. Breaking into the US market has been, and remains, the dream of every self-respecting European cartoonist there is, has ever been, and probably will ever be. But, since Eurocomics first met with the American consciousness, precious few can say they ever truly conquered America. The tide may finally be turning.

English-language editions are still the Holy Grail for European comic book authors. As the world’s lingua franca, an English translation is the doorway to expanding your readership around the world. However, the expense and risk associated with producing translations has meant, until very recently, that very few publishing houses have taken the step, much to the frustration of European authors. Breaking into the US market has been, and remains, the dream of every self-respecting European cartoonist there is, has ever been, and probably will ever be. But, since Eurocomics first met with the American consciousness, precious few can say they ever truly conquered America. The tide may finally be turning.

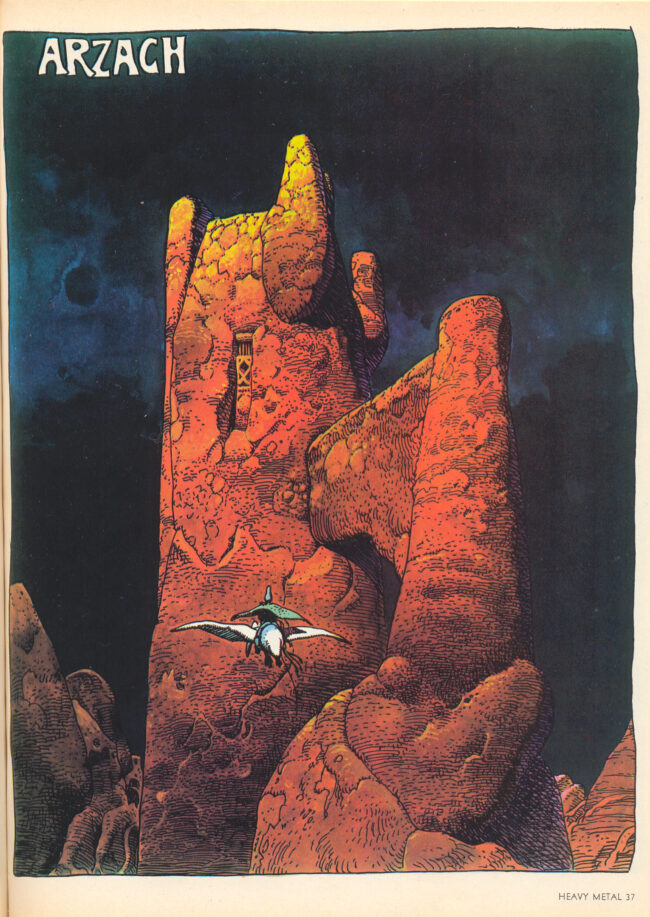

European comics were first swept into the American limelight in 1968 when Jean-Claude Forrest’s French comic-book heroine Barbarella, played by the curvaceous Jane Fonda, hit the big screen. While the effect was not immediate, it set off a slow and steady trickle of translated titles crossing the Atlantic for American readers to peruse, not least the Asterix and Tintin series’. However, despite their global success, these two titanic titles of bande dessinée were not embraced by the American public, so soon sank quietly from sight. It took the launch of Heavy Metal magazine in 1977, which showcased the work of the hottest experimental cartoonists from Europe, before things really started to snowball.

The snowball rolled only as fast as translations could allow, however, and American comics publishers were by and large unfamiliar with the challenges that translating presented. True commercial success remained limited, and very few titles beyond The Smurfs (1981) made it out of the shadows. Sometimes this was due to the poor quality of translations. Fantagraphics first foray into French BD, for example, soon ended after Terry Beatty complained that Thompson and Decker’s translation of The Survivors! was far from perfect: “Hermann's art is so superb that it is well worth the purchase price of the book - just don't bother trying to read the thing.”

Cultural differences and poorly targeted titles were also to blame for lackluster uptake. Dargaud’s translation of Godard and Ribera’s Vagabond of Limbo, which contains imagery of gay Nazis forcing deathcamp Jews to dig their own graves, was a far cry from the family-friendly titles that had preceded it. Everything involving Jean “Moebius” Giraud, on the other hand, seemed to be met with enthusiasm. (For a deeper understanding of Eurocomics at the time - check out TF Mills article in TCJ 105 from 1986 “Franco-Belgian Comics: A Success Story.”)

But, despite the early promise, faced with rising competition in the form of the 1980s manga explosion and the Tim Burton’s Batman film in 1989, much of what some had described as the “Eurocomics Revolution” was soon over, although only a few hundred titles had actually been translated. According to R. Scott’s sourcebook, European Comics in English Translation, just 500 European titles or so had been released in English by the turn of the century. The story, of course, does not end there. Although Eurocomics fell off the radar for a time, a renaissance began in the mid-noughties when titles by French independent publishing house l’Association kicked off a whole new mini-revolution; selling English rights to the highly successful Persepolis, Epileptic and Approximate Continuum Comics.

But, despite the early promise, faced with rising competition in the form of the 1980s manga explosion and the Tim Burton’s Batman film in 1989, much of what some had described as the “Eurocomics Revolution” was soon over, although only a few hundred titles had actually been translated. According to R. Scott’s sourcebook, European Comics in English Translation, just 500 European titles or so had been released in English by the turn of the century. The story, of course, does not end there. Although Eurocomics fell off the radar for a time, a renaissance began in the mid-noughties when titles by French independent publishing house l’Association kicked off a whole new mini-revolution; selling English rights to the highly successful Persepolis, Epileptic and Approximate Continuum Comics.

In Great Britain Asterix and Tintin were all there was until around 2005 when French businessman, Olivier Cadic, set up publishing house Cinebook to translate and publish Franco-Belgian comics en masse. It was a surprisingly successful venture. Some of the biggest names in French BD are now published in English under the Cinebook banner: Valerian, Blake and Mortimer, Lucky Luke, Gomer Goof, Largo Winch, XIII, Thorgal, and Spirou. Cinebook’s success led to Cadic being Knighted with the French National Order of Merit for his services to France in 2011, on top of which he now sits in the French senate as representative of the foreign nationals’ caucus. (Would Gary Groth consider a career in politics, I wonder?)

Thankfully, Eurocomic translations are now more commonplace in North America than ever before. Fantagraphics, NBM, First Second, Drawn & Quarterly, Dark Horse and others are no strangers to publishing translated titles. However, many major European authors remain unknown in North America, much to their collective chagrin.

Do not be fooled into thinking that the motivation is purely financial. Sure, the US market is big, but the French market is substantial in itself: 48 million graphic novels and comic books were sold in France last year – around 680 million dollars’ worth – which makes it almost three times larger per capita than the US market. Leading titles easily surpass sales figures for the hottest Marvel and DC titles, with the most popular shifting over a million copies a piece. You can earn a decent living drawing cartoons in Europe, of that there is no doubt, but that does not assuage authors from their desire to break into the American market.

I recently translated a book for illustrator Christian Heinrich who is known for a very successful children’s series called Les P’tits Poules (he was also one of Marjane Satrapi’s professors at Art School if you’re thinking you’ve heard the name before.) He told me that The Little Hens, as the series would be known in English if it existed, has sold millions all over the world, 50 million in China alone, but as yet no English editor has shown the slightest interest in doing a version for the American market. A case in point that success elsewhere does not guarantee success in the US.

Generally speaking, there are two ways to get a European title published in English, and both basically boil down to who pays for the translation. The preferred option for European publishing houses is to sell translation and territorial rights to US editors, at the Angouleme International Comic Con for example, and leave them to then invest in producing their own translations. While this places most of the financial risk on the purchasing editor it also guarantees editorial control over the translation for the target market. The second option is for European editors to translate their own titles and sell them as ready-to-publish products.

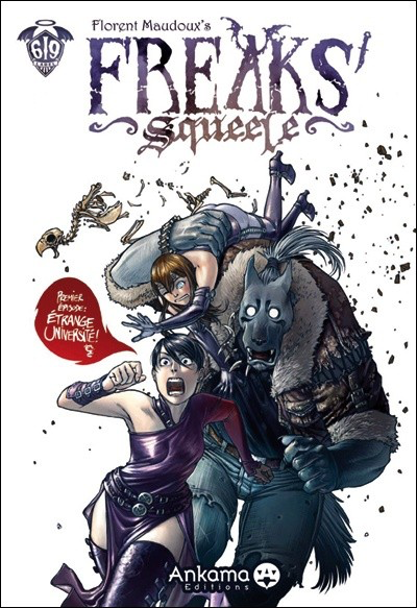

If you’re an author though, and your publisher has failed to find a buyer, there are of course other options: pay for your own translation or find a foreign fan to translate it gratis and market it yourself. This might be how Florent Maudoux’s Freaks Squeele came to the attention of Boom! Studios in 2015. A mega-fan translated the entire seven volume, 1000 page, French series for free and published it on bootleg website Mangafox, just so they could read it in English. “It was an honor to have my stuff pirated,” Maudoux told me in a brief exchange online “In France, digital versions aren’t as valued as printed ones, people check them out to get an idea of what they might want to buy, it’s a bit like visiting the library.” Unfortunately for the author, the English, printed, series was abandoned after three issues.

If you’re an author though, and your publisher has failed to find a buyer, there are of course other options: pay for your own translation or find a foreign fan to translate it gratis and market it yourself. This might be how Florent Maudoux’s Freaks Squeele came to the attention of Boom! Studios in 2015. A mega-fan translated the entire seven volume, 1000 page, French series for free and published it on bootleg website Mangafox, just so they could read it in English. “It was an honor to have my stuff pirated,” Maudoux told me in a brief exchange online “In France, digital versions aren’t as valued as printed ones, people check them out to get an idea of what they might want to buy, it’s a bit like visiting the library.” Unfortunately for the author, the English, printed, series was abandoned after three issues.

Despite his experience, Maudoux’s view seems to hold true. Digital translated versions of comic books can lead to physical, tactile editions appearing on the market. Indeed, this is exactly the business model employed by Europe Comics, a venture set up in 2015 by Mediatoon in France and Belgium, who translate and market European comic books in digital format. While the focus of the project is to sell electronic versions of both new and classic European cartoons online, its other main aim is to persuade foreign publishers to buy the rights to produce versions in print.

I recently spoke to Europe Comics Editor Christopher Bradley to ask how things were working out. (If you’re thinking he doesn’t sound too French, you’d be right – Bradley hails originally from Eugene, Oregon.) Essentially the project got off the ground thanks to the European Union, who supplied fifty percent of the inward investment from their Creative Europe program to support the translation and distribution of European cultural products. “It’s sort of like a cultural ambassador program,” he explains. “It does lead to a lot of new series being sold in English which allows all of these characters and series to make it outside the Franco-Belgian sphere. It helps the spread of BD culture, which is pretty cool.”

They have managed to publish 20 digital titles a month, on average, since it all began - meaning over a thousand new European comic titles to date. In fact, the sheer quantity of translations that Europe Comics are releasing is the main benefit to the program, but like many Eurocomics that have come before there are ones that sell and ones that don’t.

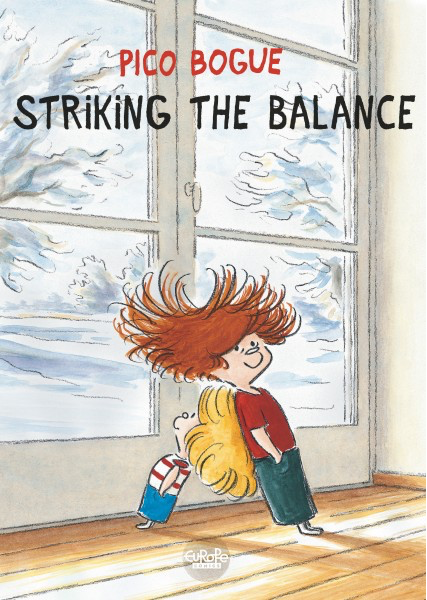

What frustrates Bradley most are the titles that get overlooked despite their obvious potential: “The one that really stuck out was Pico Bogue. It’s about this boy, he’s like 7 years old and its funny but also high-level philosophical. It looks like it’s for kids, but it has a bit of Calvin and Hobbes philosophy about it. So did people see it and really not get it or are they just not interested?”

So how many digital versions have made it into print? Bradley says that about one in ten of the digital versions they release get picked up by an English language publisher along with the accompanying translation. NBM, IDW, Lion Forge and First Second are just some of the US publishers on the client roster. One notable ‘graduate’ from the catalogue is Mister Invincible which was acquired by Magnetic Press last year. Notable because its media-subverting humor simply does not work in digital format, and also because Jousselin’s comic book hero has to be the most original strip to have come out of Europe for quite some time. Indeed, it is surprising just how long it took for Imbattable (the original French title) to get noticed. It is a remarkable book, and one that surely would have sunk from sight had Europe Comics not translated it.

The translation, like the majority at Europe Comics, is solid. However, I can’t help thinking that the English title loses something in translation. In French Imbattable (literally – unbeatable) is an utterly ridiculous name for a superhero, in English however Mr. Invincible is not. The reason for this rather flat translation is obviously due to the ‘I’ emblazoned on our hero’s shirt.

Some might wonder whether the sheer quantity of translations that Europe Comics have been working on may have compromised the quality of their translations. However, approaches to translation these days are a far cry from the haphazard efforts of the first Eurocomics revolution in the 1980s. With language professionals involved in projects from start to finish, be it in Europe or the USA, the quality of the end product is usually assured.

Some might wonder whether the sheer quantity of translations that Europe Comics have been working on may have compromised the quality of their translations. However, approaches to translation these days are a far cry from the haphazard efforts of the first Eurocomics revolution in the 1980s. With language professionals involved in projects from start to finish, be it in Europe or the USA, the quality of the end product is usually assured.

Although a thousand titles might seem like a lot, Europe Comics’ efforts account for only a fraction of the enormous back catalogue of Eurocomics still awaiting translation, not to mention the thousands of new titles that are released every year. Besides, the venture only translates titles published by a small number of Eurocomic operations that have a relationship with Mediatoon. No other European operation, as far as I am aware, has anything approaching the same level of investment in translations; EU money only goes so far.

There are of course two other paths open to European authors hoping to get their book noticed in the USA. One is to simply not bother with translating at all and hope that specialist international comic stores, like Stuart Ng Books in L.A., put your book on display as a Hollywood film producer is passing by or, the ultimate solution, of course, is to publish it in English in the first place.

Given the ease with which authors can now crowdfund their work and publish independently, perhaps the true Eurocomics Revolution has only just begun?