“A small spider lives in my body. Usually it sits quietly, deep inside. But sometimes it crawls around just beneath the skin of my arms and legs. Some day I will kill it.”

- Occupants, Kuniko Tsurita (translated by Ryan Holmberg)

Kuniko Tsurita’s comics are a declaration of their own existence. A fiercely independent artist, Tsurita overcame a sexist society and a body wracked by chronic illness to draw comics throughout her tragically short, brilliant life. As the first – and, until the mid-eighties, only -- woman contributor to Garo magazine, Tsurita’s work is unfortunately well positioned to be viewed as an outlier, an anomaly to be pitted disparagingly or superfluously either against the women who revolutionized commercial shojo manga or the men who were her peers in the literary underground. Nonetheless, her artistic voice is as singular as her career was unique, not an alternative or a derivative but an idiosyncratic grammar special unto itself. An elegant scream.

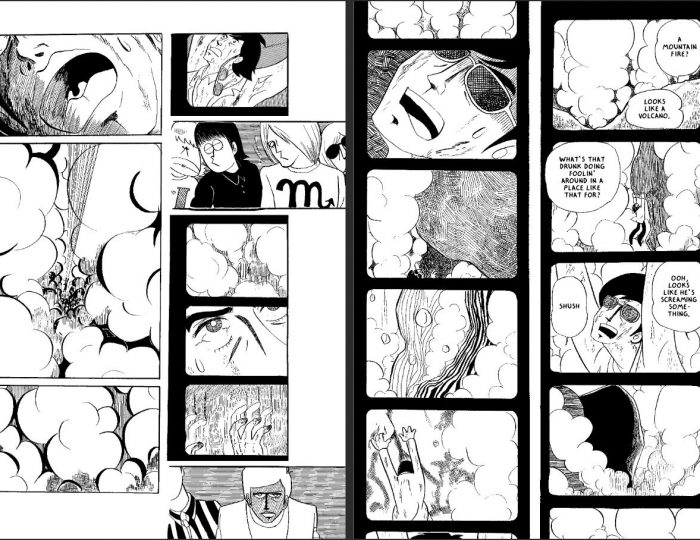

The stories collected in The Sky is Blue with a Single Cloud span the beginning of Tsurita’s mature period in 1966 to shortly before her passing in 1981 and give a picture of a versatile but struggling artist, developing and declining while never quite finding a definitive footing. The tone is brashly artsy and bluntly melodramatic, at a remove from the noirish vigor of hard genre gekiga and not so polished as the remote surrealism of Garo’s avant garde wing. Tsurita’s work runs the gamut from moody tone poem-like short subjects to sci-fi suspense, capriciously darting in and out of genre and narrative cohesion. But the mood of her work is remarkably consistent, a meditative despair, seconds before death, exhausted melodramas without a beginning that end without closure, weary faces with flat expressions and bodies contorted within graphic abstractions.

Where her contemporaries drew upon the form of postwar rental manga of which many were veterans, Tsurita to my eye seems equally indebted to the then-current stylings of the distinguished competition of Osamu Tezuka and Shotaro Ishinomori, whose magazine COM would set out to be a mainstream counterpart to Garo’s expressive cutting edge, and, to a certain extent the aesthetics of shojo manga (a genre Tsurita detested). In Tsurita’s work there is often a fondness for certain expressionistic idioms, humorous cartoon digressions and lounging laughing posture, and narratives that touch on the fantastic and a vague exoticism for Europe, often with as much kinship to be found in Princess Knight as Screw-Style. But Tsurita was a gekiga artist, and a fiercely independent one at that. Where the year 24 group found in European fantasy the pomp of Parisian royalty, roses and soft white boys, Tsurita is drawn to the hardscrabble existential nightmare side of nouvelle vague films, Bergman, Strindberg. Tsurita’s work is clearly that of a committed leftist or at the very least a woman extremely well acquainted with the spaces (and the danger, and the pessimism) of revolutionary youth groups. Thus her work is more closely recognizable in conversation with the likes of leftist, surrealist Garo contributors like Tadao Tsuge and Sasaki Maki.

Gaze is a limiting concept that essentializes both sympathy and lust on woefully reductive gendered lines. That said, Tsurita’s position as the only woman in a male-dominated field is consciously reflected in the way her stories are framed. For example, not unlike some of her contemporaries, many of Tsurita’s stories depict abusers. Money and Max in particular focus explicitly on a disturbed person’s connection to a domineering, intimidating partner. These people are frightening but they are also depicted as attractive, cool outsiders sporting leather jackets and sunglasses. Intimacy exists in these relationships, but its flaws, of grasping and recoiling, of emotional disconnect and desperate clinging, make themselves apparent to the reader whereas specific actions of aggression often may not. This preoccupation is also reflected in stories where it might not be as directly depicted – in the early genre thriller-ish piece Anti, a man commits a murder on film and impresses a student film group with a screening the results, his new picture (“Hey man, how did you shoot that part where he falls? It looked so real.”). The protagonist of Anti is socially embedded within a group of admirers who he has conditioned through his mix of charisma and active displays of destructive behavior to disregard the plain evidence of his predation, a tactic not uncommon to real life abusers. He also happens to be gorgeously handsome.

I can’t help but look at these stories in comparison to the sensitive explorations of women’s suffering and personal guilt in the gekiga of Seiichi Hayashi or the I-novel solipsism of Yoshiharu Tsuge’s The Man Without Talent or Shinichi Abe’s That Miyoko Asagaya Feeling. The subject matter -- the toxic relationships of struggling artists in abject poverty -- is the same, but the focus is different. Hayashi is a feminist, Tsuge and Abe are misogynists, all three are great artists and theirs are stories of guilt and longing intertwined for women who suffer under men. They do not identify with the victims of their stories and do not observe exactly what Tsurita dwells on, the inner world of victims and survivors, a world where we may still see a certain allure, even poetry, to the people who hurt us and the sensation of being hurt. It’s a compelling difference in perspective that one simply cannot expect to find in Tsurita’s contemporaries.[1]

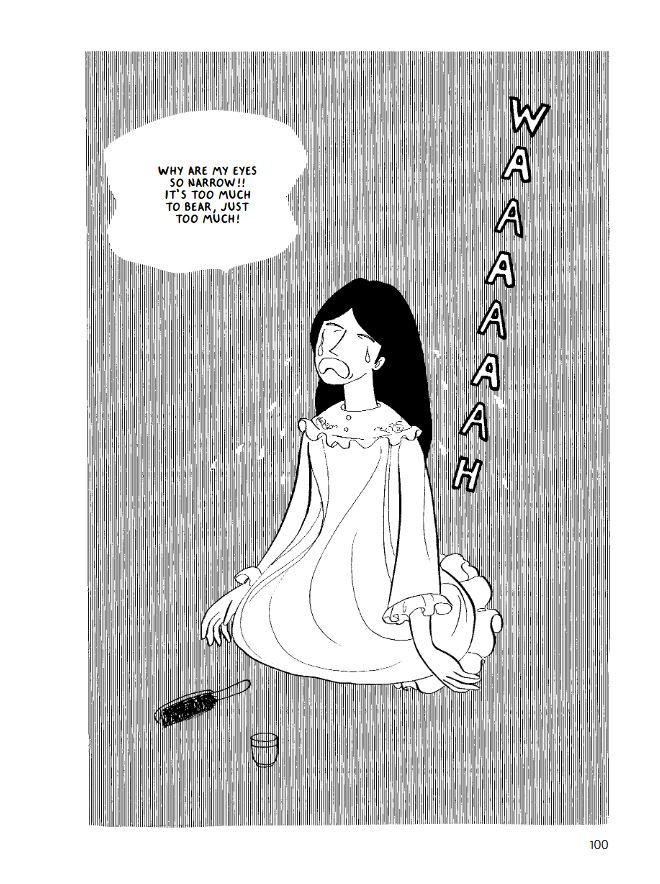

In the short comic “The Tragedy of Princess Rokunomiya,” a woman with a cold expression goes about her day, ignoring the catcalls of aroused men and the whispers of gossipy women intrigued by her mysterious visage. Something about her suggests a darkness, a trauma, a secret bottled up behind her icy gaze. Finally, alone after a long day, she cries, and we learn her tragic secret: “Why are my eyes so narrow?” she wails, “It’s too much to bear, too much!” This cartoon trait, naturally, is the very visual shorthand signaling her intriguing coldness. The facet of her appearance that makes others imagine her as a tragic, unapproachable figure is in fact the tragedy. It is a joke about cartoon idiom that mocks the self-serious style of Dramatic Pictures and the nature of the sympathies that the genre privileges. Not liking your face is a silly problem and yet that sort of superficial dissatisfaction is the kind which can dominate life. Her problems are not “interesting” or dramatic in the neoliberal lens of social realism or genre entertainment which elicits sympathy through the satisfaction of dramatic, displayable pain, yet her trauma is nevertheless literally written on her face.

This is not the most spectacular or characteristic work in the collection but I highlight it because it may serve well as an instruction to the reader -- these works convey an emotional experience that simply isn’t explored in other works, and indeed the pain of being alone in sharing those experiences. It isn’t a more lurid, more important, more real pain -- Rokunomiya’s “tragedy” in fact is unexpectedly mundane. But it is real, it is intense, and it is neglected and misunderstood by those around her who speculate on its nature.

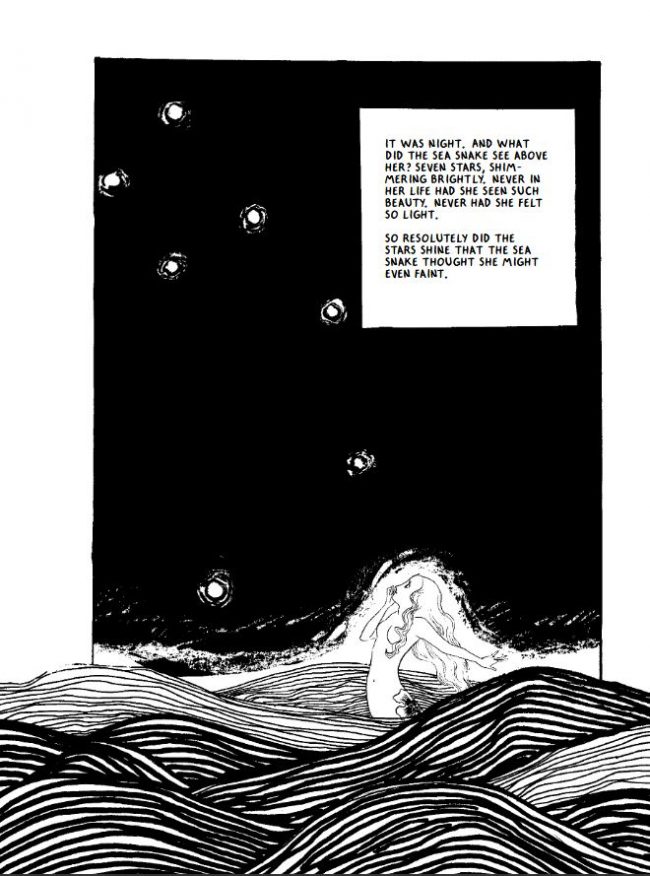

Tsurita’s comics dwell on death and self-annihilation, isolation, dysphoria and longing. Her protagonists are often trapped in their bodies, constrained by an inner decay even as their surroundings may seem invitingly open, full of possibility and negative space. They are trapped by society, they are trapped by their partners, they are trapped by minds and bodies that cannot perform. Nonsense and Calamity both focus on men falsely accused of a crime and sentenced to death, suggesting Kafkaesque parables and functioning as such in broad strokes, yet far more evocative as expressions of the panicked despair of existing in a society that vilifies people incapable of conforming to its expectations, expectations that I would note include being able-bodied, neurotypical, and not prone to suicidal ideation. Her later stories expand more overtly on this subtext as overt imagery, often of drowning -- the titular wife of My Wife is an Acrobat sinks into her bath, declaring herself “dead and pickled in alcohol”; the heroine of the adult fairy tale Sea Snake and the Big Dipper freezes to death on the ocean’s surface, content to gaze upon the constellations which she cannot reach.

The musings of Tsurita’s protagonists on their fast-approaching doom may appear to some glibly nihilistic, an easy surrender to depression. It is true that Tsurita’s characters wallow in their inevitable misery but it is unfair to read these preoccupations as resignation. These stories are affirmations of people too weak and wrecked by disability, trauma, and sadness to satisfy the expectations of personhood, able neither to succeed nor to be recognized as comprehensible tragedy. “My life is me,” says the protagonist of Max, “I will leave nothing behind…When I die, even my friends will forget that I ever existed. I will simply disappear.” While fatal, the sentiment nonetheless confirms their existence -- they do not need to be remembered to justify their being. The stories in this collection return constantly in their focus to a gnawing internal emptiness, bodily dysmorphia, a yearning to cease, a sense of separation from some brighter realm. And yet, taken as a whole, their misery is joyous. Tsurita clung to her life through chronic illness that must have made her already marginal existence agony and in comics she found a means to both release and share that pain as something beautiful. Each page in this collection is a manifestation of her will to live, to create, to express herself and be seen if only for an instant.

Tsurita’s work also takes a leap that her contemporaries at Garo rarely if ever matched, albeit one with parallels in the commercial shojo manga that she decidedly stands apart from -- the blurring and outright destabilization of binary gender identifications. It is not an unusual experience reading manga to be unsure if a character “is a boy or a girl,” but in many of Tsurita’s works the potential of that ambiguity is taken further into outright confusion, muscular bodies sporting willowy hair, mixtures of soft and hard appearances that defy categories.[2] And unlike the Takarazuka revue-inspired femme-y bishonen of commercial shojo manga, the reader is never alerted to the gender identity of these characters through dialog or context. The Japanese language allows greater ambiguity for grammatical gender than English, but this possibility is often unfulfilled because the hierarchies embedded in speech especially in first and second person pronouns signal not only gender but status. Reading these works in translation it is hard for me to judge the extent to which gender ambiguity destabilizes social norms in these works but one suspects the intent is radical.

Although this is a different (and potentially more explicitly disruptive) approach to gender than that found in in the shojo manga contemporary to Tsurita’s work, I am nonetheless reminded of an observation on the boy’s love phenomenon,[3] that the genre provided girls with the validation of seeing their emotions reflected in the socially segregated, privileged experiences of boys. Tsurita’s stories are about women – traumas, emotions, and marginalization that women experience and are rarely given conventional venues to express without conforming to the expectations of kyriarchy. Paradoxically, Tsurita is able to open this emotional space because she does not allow her stories about women to be about women – as her frequent refusal to clarify genders exemplifies, Tsurita defies not only the silence imposed on women but also the limiting constraints of gendered concepts like “woman” as a tool of that very silencing. There’s a bit of sensuality and gestural physicality in every bodily form on the page, and in every character both a little humanity and a little eeriness, alienating presences overflowing with emotion that redefines boundaries even in their dysmorphic anguish. Tsurita captures experiences that are trivialized along gender lines while almost casually rejecting the voyeuristic assumptions of patriarchal interpretations that we can all too easily mistake for sympathy when we impose them onto stories. The backmatter essay by Holmberg and Asakawa somewhat awkwardly speculates as to whether or not Tsurita was a lesbian,[4] but it is this refusal to satisfy normative sexually reductive conventions for her readership more than any defined sexual orientation that for myself as a reader make Tsurita’s works resolutely, necessarily queer, simultaneously empathetic and alien in their transgressions.

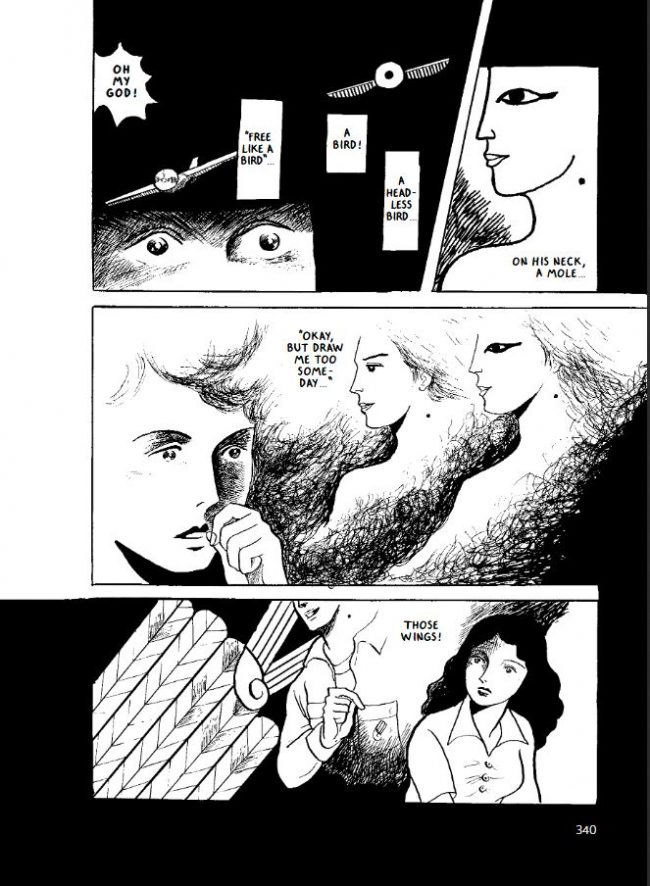

The final story in the collection, Flight, is not in fact a work of gekiga at all, but her mainstream magazine debut in, of all places, Young Jump. Per Holmberg and Asakawa’s supplementary essay, Flight was drawn by Tsurita while hospitalized, a “declaration of life” made in direct disobedience of doctor’s orders to rest. That labor may have contributed to the weak constitution which killed her. It is a work born of desperation, to make art, to be able bodied, to be expressive, to bring home a paycheck. Flight is a resolutely full genre piece, a weepy science-fantasy romance centered around the exoticism girl’s fiction trades in – a girl’s pilot boyfriend vanishes in a mysterious storm, and Egyptian hieroglyphs reveal to her that he in fact slipped through time. Like the protagonists of Tsurita’s experimental works, and indeed, Tsurita herself, the boyfriend is at once dead and forgotten and alive, preserved curiously in the hieroglyphic picture stories that M. Night Shyamalan would remind us are not unlike a comic book. Aesthetically and narratively the work itself beautifully reflects the desires it was born out, an otherworldly piece of pulp unstuck in time. Styled like genre fare ten years older than itself, Flight is at once a revision and reclamation of genre, an alternative, personal art built upon the language of fiction so gendered and infantilized even the artist herself looked down on them. I truly cannot think of many comics that look and feel like this. I do not know whether Tsurita was proud of this work – the backmatter discusses Flight as a triumphant achievement for Tsurita, a boast that she could make this kind of art, but with Tsurita long dead and gone we can only really trust others speaking for her on this, others invested in an optimistic view I suspect – but to me a comic like Flight has to be a triumph, a story that at once entertains and captures through allegory an extremely specific, marginalized emotion, drawn with an energy that lets you know that every mark on the page wanted to be made and seen regardless of whether it would ever be remembered or understood.

I have a suspicion that many critics are going to struggle to talk about Kuniko Tsurita’s work, and in writing this essay, I myself have struggled. The standards of critical discourse do not have much room to articulate or even recognize the artistic expressions of traumatized people and survivors of abuse, especially when they are the expressions of women. There is much in Tsurita’s work that will scan to many readers as adolescent, amateurish and pretentious, the fatalism and straight-faced melodrama of her art more embarrassing than the hardboiled pulp and measured avant garde of the other Garo greats, works with greater purchase within preexisting literary canons. But Tsurita is writing from the perspective of experiences that those canons still strain to reflect, not only of womanhood but of trauma and survival, of disability and chronic illness. I worry that in my attempts to defend Tsurita from ungenerous readings I am simply setting her up to be read from an apologetic stance, “just as good as” or “better than you realize.” Let me be clear: Tsurita’s comics are a revelation.

[1] Hayashi’s young men do tend to be pretty good-looking, but that’s not exactly what I’m talking about.

[2] To be clear, Tsurita does not always make the gender identities of her characters ambiguous – one early story, a wordless piece about a suffering cavewomen, is literally titled “WOMAN”.

[3] I had recalled this being in one of Rachel Thorn’s introductions for the Moto Hagio books published by Fantagraphics but having just skimmed these I do not think that this is the case. If someone with a photographic memory of late ‘00s/ early ’10 shojo manga discourse can help me find attribution or take credit for this observation I will happily revise this piece to add an acknowledgement.

[4] The essay is otherwise excellent and as informative and interesting as any that Holmberg and Asakawa have written. It is the most detailed and heavily researched writing in English on Tsurita that I know of and benefits from the consultation of Tsurita’s widower. I absolutely do not want to suggest that Holmberg and Asakawa have written anything sexist or insensitive. However, there are several passages that might have benefitted from the involvement of a feminist or queer scholar, for clarity as much as anything.