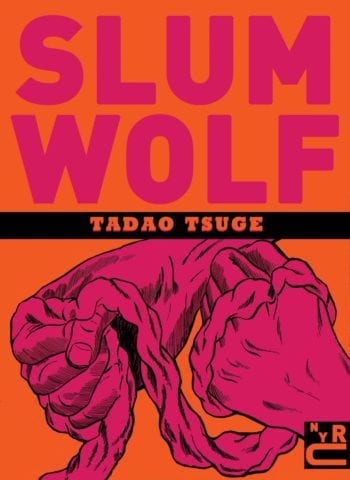

At last, Tsuge Tadao’s Slum Wolf is on its way to the printers. If what I do is a labor of love, this book confirmed that I am a blind slave to my passions. Not only was the translation the trickiest of any of the projects I’ve been involved with, but I have never had to struggle so much with an essay to get it right and under control. Hopefully, the world will find the final product worthy of its support to ensure happier and smoother times for New York Review Comics’ future manga projects – of which there will be more.

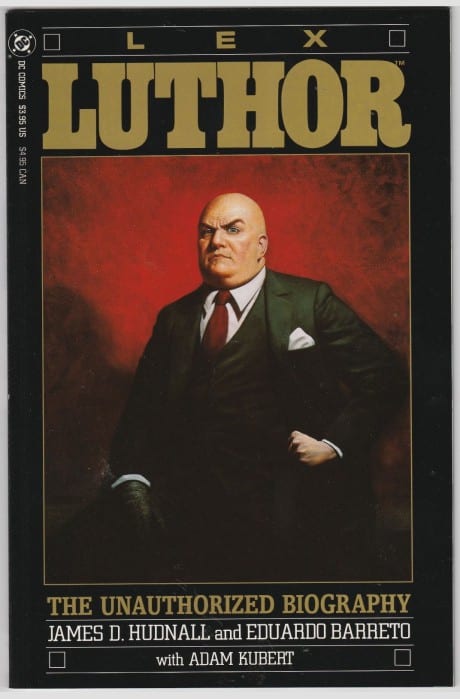

If you are a glutton for punishment, as I am, it is important not to make things simple for yourself. A good way to do this is to change your mind a lot after having already started doing the work. Of course, sometimes one can only see better solutions after first struggling with poorer ones. For example, the original plan for the supplemental material for Slum Wolf was to include an interview between the artist and Garo editor Takano Shinzō (b. 1940) from 1969. The translation was submitted and checked, then many months passed, then the project was revived, then I realized that it made more sense to pick up where I had left off in Trash Market (Drawn & Quarterly, 2015) and translate the remaining chapters from “The Tadao Tsuge Revue” (1995-96) that relate to the artist’s childhood as a postwar slum urchin, memories of which serve as the conceptual and historical landscape to the manga in Slum Wolf. The interview also has a lot in it that would have required more explanatory notes and reference images than the project reasonably allowed. So here it is instead online, where more images only mean that you have to wait a little longer for the page to upload, and where digressions seem naturally bloggy. As many of the images here are from the forthcoming book, this post is essentially also a preview of Slum Wolf. It introduces the two stars of the new book: Keisei Sabu, the ex-kamikaze turned thuggish black market heroic, and Aogishi Ryōkichi, the army veteran who cannot square what he saw and did during the war with settled, postwar, middle-class life.

Though the translation here is a fuller version than what was to be in Slum Wolf, still a few lines have been removed to avoid repetition and tangents that take the conversation too far away from the focal topics. Those topics are: how Tadao got into comics and what the practice means to him, how the early postwar period (roughly from 1945 through the Korean War) forms the bedrock of both Tadao’s work and Takano’s conception of what authentic gekiga is, and how both were committed to non-ideological understandings of class and the war as truer to the experiences of the average Japanese person. You might find the conversation lacking momentum at points. However, you should read that very fact in relationship to the discussion about ellipses and the unspoken and inexpressible that occurs halfway through. For then you will see how certain modes of inarticulate speech were embraced as positive aesthetic and social forms by Tadao and Takano. With so much ink spilled about figuration, layouts, and image/text relations in comics theory, it’s refreshing to find someone attending to the fact that comics are often structured around speech situations.

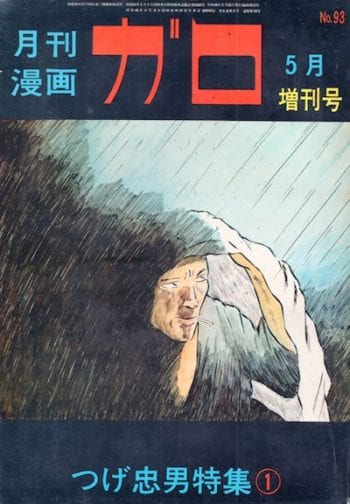

Tadao had only published a handful of works in Garo when this interview was conducted. It makes default sense to begin an interview, as Takano does here, by asking an artist about his debut years. But furthermore, by trying to get Tadao to talk about his kashihon (rental book) period in the late ‘50s and ‘60s, Takano was also attempting to establishing spiritual links between the practically extinct world of kashihon manga and the kind of gekiga he was supporting as an editor in Garo. Gekiga understood as gritty and authentic stories of the underclass, rather than bombastic long-format action comics (and action sex comics) for young men, owes much to the critical discourse established by Takano (under the penname Gondō Susumu, also used for this interview) and his colleagues at Manga-ism (Manga shugi), probably the world’s first journal dedicated to serious comics criticism, in the late ‘60s and ‘70s. You can read more about Takano’s background and his seminal activities as an editor, critic, and publisher here, in my introduction to a translation of another Garo-based interview from 1969.

Thank you to Gabriel Winslow-Yost of New York Review Comics for his warm and attentive support of all phases of Slum Wolf, including his comments on the initial translation of this interview. If you are interested in following the progress of my research and publications, check out @mangaberg on Instagram.

“The Weight of Postwar Life,” Garo no. 64 (August 1969). Translated with the permission of the interlocutors.

Takano Shinzō: Let me start by asking you a standard question. When did you start drawing comics?

Tsuge Tadao: I’m not sure. I drew a bit for Wakaki Shobō and Sanȳosha [which later became Seirindō, Garo's publisher, but I suspect they only paid me out of pity. I couldn’t draw worth a damn. I deserved to be paid.

TS: Wakaki Shobō and Sanyōsha ... that must have been around 1959 or 1960. You would have been a teenager still.

TT: Yeah, probably 17 or 18. For Wakaki Shobō, it would have been earlier. I don’t own any copies of things I drew back then.

TS: Seems like you made a lot of thriller stories.

TT: Yup, that was the golden age of thrillers. After that was the golden age of jidaimono [historical fiction], so I thought I had to start drawing those, and that’s what I drew for Sanyōsha.

TS: Why did you start drawing comics? Was it to make money?

TT: I think so, but I don’t really remember.

TS: How did you feel about drawing comics once you started?

TT: Nothing in particular. I didn’t have anything better to do. I was just hanging out in cafes and shooting the shit with my friends every night.

TS: So you didn’t have any intention of becoming a professional manga author at the time?

TT: Not at all. I had no idea how long I’d be able to continue drawing.

TS: Looking at copies of The Labyrinth (Meiro) from that period, the publishers call you “Genius of the Short Story, Tsuge Tadao.”

TT: Oh really? My brother [Tsuge Yoshiharu] probably came up with that. He was serving as the editor of The Labyrinth.

TS: Even reading it now, I still think “The Sculpture” (“Aru chōzō,” Meiro no. 1 (January 1960)) is pretty good. Most thriller works just leave you with a scared feeling, but “The Sculpture” makes you feel something like the heaviness of life and death. While reading it, I wondered what kind of things you might have been thinking about when you drew it.

TT: I like that work too. I thought I had come up with a good story, and showed it to my brother. He read it through twice, said “Oh, I get it,” then I heard nothing from him after that.

TS: It’s only eight pages long, but it’s all about the character’s internal psychology. In that sense, it’s a difficult work. For readers who do get it, I imagine some of them wish they’d never read the story. Or maybe that was precisely the kind of experience customers of rental bookshops looked for.

TT: Sure . . . but exactly because it’s that kind of work, since no one knew who I was, I imagine most readers just thought, “What the hell is this?”

TS: What did you think about gekiga?

TT: At the time, gekiga anthologies like The Shadow (Kage) were pushing their way into Tokyo from the Kansai [Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto] region. I was really turned on by that stuff.

TS: Yet your roots were in Tezuka Osamu.

TT: That’s true.

TS: And then you quit drawing comics and got a job?

TT: Actually, I started working right after graduating from middle school. I quit when I started drawing comics, then got a job again after that.

TS: Why did you stop drawing?

TT: Because I thought I was no good, I thought I’d never make it.

TS: So that means that, between then and last year, when you published “Insects” (“Mushi”) with Tōkōsha [in Ikegami Ryōichi's Shiroi ekitai, May 1968], you hadn’t drawn anything?

TT: Pretty much. Except for something I was working on slowly at home with the idea of eventually submitting it to Garo.

TS: What had you been doing in the meantime?

TT: I was really into literature. My friends and I created a mimeographed literary magazine. I liked Oe Kenzaburō and Kaikō Takeshi, and thought I might try to write a novel (shōsetsu [which includes texts shorter than what that word usually signifies in English]). But we were lazy about the literary magazine. It started with issue zero and ended with issue one. [Laughs]

TS: Were you not into comics anymore?

TT: I think I’d completely forgotten about them.

TS: So, then, what inspired you to draw “Insects”?

TT: I had just gotten married, and was a bit bored. Sorry, I know that sounds awful. But then once I started drawing, I really enjoyed it.

TS: Did you think you wanted to keep drawing comics after that?

TT: Not really.

TS: Listening to you now, I don’t get the sense that you felt that you just had to get your work out into the world.

TT: I had been working on something like a novel with my friends, and then I guess at some point went back to comics. To be honest, I’m not really sure what happened. It just happened ... that seems to be my mode of operating.

TS: I imagine your feelings about drawing comics have changed somewhat now.

TT: That’s true, now I really enjoy it. I get to draw what I want without anyone putting restrictions on me.

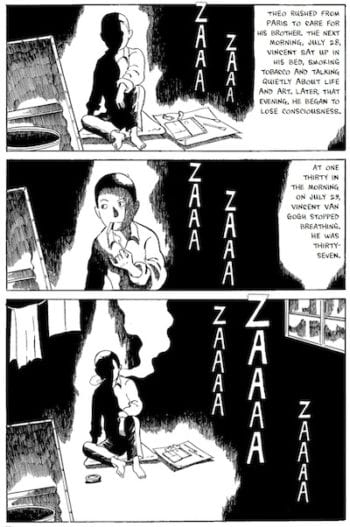

TS: The first story you published in Garo was “Up on the hill, Vincent van Gogh...” (“Oka no ue de, Vincento van Gohho,” December 1968). Was that something you had wanted to draw from before?

TT: The original plan was to write it as a prose novel. I did some research on Van Gogh and wrote things up as a proper text, but then I thought it’d be interesting as a comic, so I drew that. It was something I wanted to draw regardless...

TS: Was the prose version the same as how the manga turned out?

TT: No, they were totally different.

TS: For you, is there any difference in writing something as prose versus drawing it as a comic?

TT: Not really.

TS: When I first saw that work [Takano was managing editor at Garo at the time], I thought about how much it read like a novel. It also felt like someone’s “final work,” and I remember that making me shudder. Like, once an artist goes this far, what else is there left for him to do? Even if he had other stories in him, could he draw them?

TT: That story was something I was happy working on a little at a time. If Garo had rejected it, that would have been fine with me too. I had a full-time job at a company, so I worked on it slowly after coming home from work. That sure was a strange way of working.

TS: It’s not like the young man in the story is super serious or anything, and the work also has its humorous moments. However, precisely because of that, it gives the story this heavy crushing feeling. You know in the last scene where he lights a cigarette? It’s too quiet. The emptiness consumes everything... In pursuing Van Gogh, it’s like he said everything he could about himself, like it was all out in the open. That’s why it felt like a “final work.”

TT: A friend of mine who is a schoolteacher read that story and said, “Damn, that’s bleak.” I took it as a compliment.

TS: After “Vincent van Gogh,” the tone of your work changes. Do you think there’s a difference between something you just draw for yourself and something you draw because someone has asked you to?

TT: For sure. I’ve only published six stories in Garo so far, but the ones that really stick with me are “Vincent van Gogh” and the one I drew after that, “Sentimental Melody” (“Natsukashi no merodii,” January 1969). I would like to draw something else in the vein of “Sentimental Melody.”

TS: After reading “Vincent van Gogh,” I was apprehensive about what you would do next. A distinct image came to when I saw the title of “Sentimental Melody.” I was sure I knew what kind of work it would be. And, lo and behold, I was right. That made me really happy. The subject matter of “Vincent van Gogh” and “Sentimental Melody” are different, yet I totally get why one followed the other.

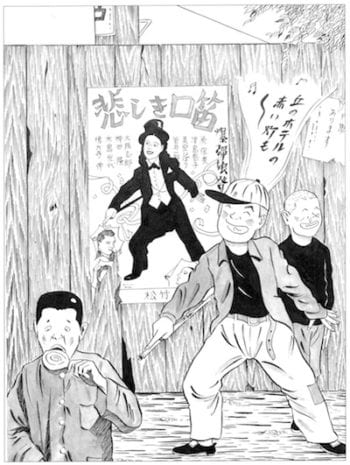

TT: “Sentimental Melody” was something I drew because I wanted to draw it. Though the idea changed in the process. I never actually saw Keisei Sabu [the central character in the story] with my own eyes, I only knew him by name.

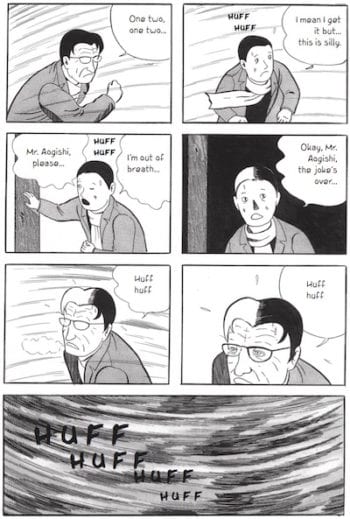

TS: What reading this work made me wonder was what “the postwar” means to you. After “Sentimental Melody” came “The Flight of Aogishi Ryōkichi” (“Aogishi Ryōkichi no haisō,” March 1969) and “Song of Showa” (“Shōwa go’eika,” April 1969). These works really make one think about the meaning of the postwar and the immediate aftermath of defeat.

TT: I will never forget the things I saw and heard while I was in the first and second grades. No memories are clearer than those from that period.

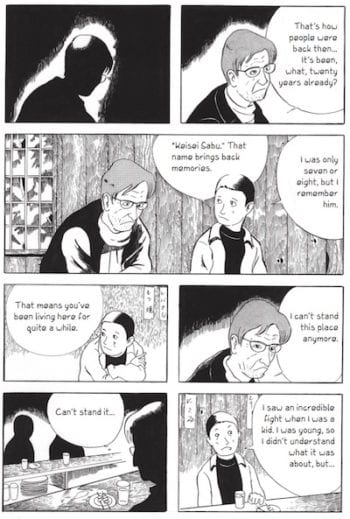

TS: That’s for sure. What happened in the chaos and ruins after the war has really stuck with me too. That said, I think “Sentimental Melody” and “The Flight of Aogishi Ryōkichi” are more than sentimental trips down memory lane. For me, it’s not about enduring the unendurable [a reference to Emperor Hirohito’s national surrender speech on August 15, 1945]. It’s more like, I don’t know, just sitting tight and living in the present. Your middle-aged man who looks like he’s from the war generation [senchūha], he’s so realistic it’s frightening.

TT: The boy in that story would have been in first or second grade [at the time of the war]. The middle-aged man is around forty-five. I wanted to draw how the two of them processed things. I wanted to draw the differences between how the boy and the man viewed Keisei Sabu. The idea was to have them talk to one another, but as I was drawing the work I ran out of things for them to say.

TS: Huh. I thought that you maybe understood the middle-aged man’s feelings too well. Reading the work, I got the sense that you had invested your own feelings in him. That’s why he comes off as so realistic.

TT: I think, in his case, it’s about things being more than he can bear.

TS: The middle-aged men in both “Sentimental Melody” and “The Flight of Aogishi” are expressionless. It’s hard to tell what they’re looking at. Maybe they’re not looking at anything, or maybe they are. Either way, one understands whatever it is that is hidden, or that they are intentionally hiding, behind that expressionlessness.

TT: People like him, they experienced the war. But what does the war mean to them? What did it mean to them? That’s what I wonder about. People our age, we only really comprehend what happened at the end of the war. At night, from the air-raid shelters, we witnessed airplanes in flames streaking across the sky. That’s all the war was for us. But for them, they had to deal with a variety of problems when the bombs fell...

TS: What is it about the war that’s so engrossing?

TT: I don’t know. There must be a lot we don’t know about. Talking to people, you often hear them say that they never want to go war again, that the war was really horrible. But I feel like that’s not the whole picture... It’s not that I don’t believe what they say, yet I can’t help but suspect that they’re hiding something.

TS: The middle-aged men in “Sentimental Melody” and “The Flight of Aogishi” are practically the same type of character, or at least they share the same generational experiences and emotions. Do you feel confident in portraying people from the war generation?

TT: I’m not sure. When I was working full-time, I met all sorts of people. I didn’t hear anything like what you find in my comics, but watching those older people, and listening to them talk and watching their expressions, I honestly don’t get what’s going through their minds. I tried to imagine how things would be for someone in a certain kind of situation. It doesn't go deeper than my imagination.

TS: If one only looks at the surface of society, you would never notice that these kind of people exist.

TT: That’s true. Nothing dramatic happens in their everyday life. But I imagine that people who experienced the war feel some sense of responsibility for it, in the broadest terms.

TS: I suspect that’s the case for only a handful of them. I imagine life’s hard for those who feel responsible for the war. They probably live burnt-out lives like the men in “Sentimental Melody” and “The Flight of Aogishi.” But there can’t be too many people like that. If you have to live with that sort of heavy emotional or psychological burden, you must have to avoid expressing it outwardly in your daily life. Such people probably just disappear without us ever having known they existed. While reading your work, I couldn’t help but think about stories and poetry written by the war generation, by people like Umezaki Haruo (1915-65) and Ayukawa Nobuo (1920-88).

TT: What fascinates me is how those people feel today about what they did during the war. I thought about that a lot especially while drawing works like “Sentimental Melody.”

TS: They probably go on with their lives despairing about the void, or maybe they’re not even capable of despairing.

TT: War war war consumes one’s life like a fever, then all of sudden it’s over. How does someone live life after that? Were they able to just, snip, start fresh? They don’t look bothered now, but who knows what they’re really feeling.

TS: I’m sure there were all types, but I imagine most people were able to adapt successfully. Ten years or so ago, intellectuals fought amongst themselves about issues of war responsibility, though nothing significant came out of it. Some intellectuals of the war generation insisted how it was necessary to tell people about the war, while others said that would get communicated even without proactively doing so, but I couldn’t care either way. Then reading your work, I got to thinking that, whatever the war generation said or didn’t say, those experiences would come across. Though I felt despair about how your story ["Sentimental Melody"] concluded, I also felt happy about the sympathy I felt with the characters.

TT: Those experiences really do get communicated regardless. It’s definitely a strange thing.

TS: There is pretty much nothing on this topic in manga. So seeing it in your work was, first of all, a pleasant surprise. Your stories have the philosophical weightiness that one finds in Umezaki Haruo’s Illusion (Genke, 1965), or in Shiina Rinzō (1911-73) and Shimao Toshio’s (1917-86) stories. But unlike Umezaki or Shimao, you don’t belong to the war generation, so one can’t but wonder what’s at the heart of your work. I feel like I understand where you are coming from, in my own way...

TT: It’s probably because I’ve come into contact with all sorts of people. Older guys get together for end-of-the-year parties and whatnot, right? They start drinking, and first they just talk bullshit, but then they always end up on the war, like about ther experiences in the military. But not in hushed tones. They’re laughing and having a good time. I wonder if that’s the only way they can talk about those things. The mood is usually not dark.

TS: My father gets excited when he talks about the war, too. He’s never said much to me about it, but apparently once he gets going he doesn’t stop. It’s been twenty-four years since the war, but for him it’s like it was yesterday. It’s like he’s still living during the Greater East Asian War. On the other hand, sometimes he badmouths the war, and he often has nightmares. But even now, it’s almost like he lives for the war. What I really want to know they managed in that void after the war, especially right after the surrender.

TT: Yeah, how did people think and get on with their lives? I can remember running around at night trying to buy food because there was so little. Presumably they were doing the same thing.

TS: Then all of sudden it was “the society of prosperity” (han’ei no shakai).

TT: Exactly. Things were great as long as all you did was talk about war, that is, as long as there wasn’t an actual war.

TS: Hmm, I wonder about that.

TT: It wasn’t like today, when everything is rational and your life is calculated. I don’t have any big ideas about what it means to live a human-like life, but I wonder if that was life back then, without pretensions or anything.

TS: I can’t remember if it was Shimao or Umezaki, maybe it was both of them, but they said something interesting to the effect that the war was the most fulfilling [jūjitsu] time of their life. I have a vague idea about what they mean, but the real truth of it is hard for me to grasp. And how that sense of fulfillment compared with life before they were conscripted, that something’s that I really don’t know anything about.

TT: People often refer to the years before World War II as “the good ole days,” but what are they referring to exactly? I wonder how that era compares with now.

TS: I feel things are the same now. You end up seeing things that way as you get older and your perception of the world and sensibilities get ground down and polished. Maybe in two or three years, right now will be the “good days.”

TT: Maybe people had more time and space in that era. People refer to the present as the “Shōwa Renaissance” [Shōwa genroku, suggesting a revival of the late ‘20s and ‘30s], but I wonder if life is more constrained now than it was back then...

TS: I can’t imagine someone like Aogishi Ryōkichi thinking about the past as the “good ole days.” There’s a fundamental difference between people who think about the past in that way and people like Aogishi who have to bear the burdens of the war.

TT: Yes, that’s how I hoped readers would see him. What’s wrong with having people out there who aren’t always acting happy, who don’t necessarily accept the past as the “good ole days,” who have to bear the past?

TS: Sorry to change the topic suddenly, but what are your thoughts on disabled veterans?

TT: I’m not sure how to answer that, other than to say that they give me the creeps. Like, why do they have to stand around in public like that?

TS: You used to see them often in the underpass in Ikebukuro. When they weren’t there, it was always a relief. But then you’d miss them and wish they were there. Some people say that they’re phonies and should be chased away, but I wonder if that’s really why they don’t them there. I think instead it’s because they can’t stand seeing them. Which simply goes to show that everyone bears the pains of the war in their own way.

TT: I can look at disabled vets from afar, but close-up I have to look away.

TS: It isn’t the same as disabled vets, but I suspect some might people read your work and think, why this topic now, what’s the need to represent it today? But one could also say, now is precisely when we need this kind of work. And I’m not just talking about my own tastes. I think this kind of work means a lot for the present.

TT: That could be. I’m drawing it now because I want to, but also because I want to now.

TS: There must be vast differences in people’s nostalgia for the physical landscape of the postwar period. But why is it that the period immediately following defeat always comes to mind? How about you, are you interested much in the years beyond those?

TT: Not really. Those shanty shops were everywhere immediately after the war. Then it was like someone suddenly ripped them out. I have no idea how they got there. At any rate, I don’t feel strongly about anything I see or anything I listen to these days.

TS: So that’s why you depict these conversations with the war generation...

TT: They are easier to draw on an emotional level.

****

TS: Another thing about your comics that interests me is your frequent use of ellipses in dialogue. You are quite particular about dialogue.

TT: Yes, I’m pretty careful about this. When people talk, they usually don’t speak smoothly. They break off here and there.

TS: What the picture can’t cover, and what the dialogue can’t cover, that becomes the ellipsis. That’s how it feels to me. What can’t be expressed is condensed in the ellipsis, so there’s a deeper meaning to your ellipses.

TT: Someone speaks, then stops and maybe wants to say something more, but they can’t... You stop once, then say something, then stop again. That’s what everyday conversation is like.

TS: That’s definitely true. Since you can’t find words for what you really want to say, the most important things might be buried in that silence. Those ellipses are like the symbolic expression of living thought, which has nothing to do with political ideas or ideology.

TT: When I am drawing, I often think that I could easily express things by adding this or that word. But then I don’t put it in, and before I’m able to find different words, I get stuck. That happens to me often.

TS: You already see that in your work around the time of “The Sculpture.” The deeper you try to go, the harder it is to communicate. If you haven’t already made a connection with the person, then they’ll probably think that you just don’t make any sense. It’s not enough just to pay attention the words. You have to listen to that silent voice between the words. That’s what I felt reading the conversation between the boy and the middle-aged man [in “Sentimental Melody”].

TT: In reality, there would be no need for them to say anything to each another. But with comics, you have no choice but to do it that way.

TS: The middle-aged man’s feelings only really come out through what the boy says. In that sense, you wouldn’t have been able to draw the situation without the boy.

TT: Yes, the boy understands everything. He even knows what the man’s going to say next. Since that’s how the situation is constructed, he can speak coldly to the man, or preempt the things he says. I was fairly careful about these things in “Sentimental Melody.” My hope was that readers would understand both of their mindsets... The people who live the most normal, invisible kind of lives, they’re the ones who I think felt things most sharply. It’s because their experiences of the war were so heavy that they now live the most withdrawn lives.

TS: After “The Flight of Aogishi” came “Song of Showa.” This work also blew me away, but maybe we should talk about that work some other time. By the way, I don’t think any other young comics authors or fiction writers deal with the world that you do. I wonder why that is. I find it strange. Maybe young artists starting out simply don’t see any point in depicting that kind of world...

TT: Probably. Could be. Like, why are you bothering with this topic now? I definitely think it was good that I had a full-time job at a company. It’s easy to depict things that you’ve experienced yourself. Right now, I have a job delivering gas tanks, and each tank weighs about 100 kg. You have wrap both of your arms around them to pick them up. When they told me 100 kg, it sounded heavy, but in actuality it was way heavier than I expected. Like super heavy. Having experienced that super heaviness that makes a difference when you draw it on paper, because you know just in what way it feels heavy. It’s actually scary. If you drop 100 kg on your foot, it’s going to get crushed. When you take one off of a vehicle, it really goes G-DONG! You support it with your body, but it’s really frightening.

TS: Wow. Listening to you talk, I can almost feel the weight... When you’re on the job, you’re probably too consumed to think about anything.

TT: Nothing, it all goes away. You think about nothing. That’s why I have no use for explanations. That’s how I feel, so I imagine other people do too. There’s nothing cool about having a job. I don’t think anyone feels cool while working.

TS: That’s probably where your desire to depict those invisible and hard-to-see parts of people’s lives comes from.

TT: Yes, the ignored part of the lives of people who just do their thing and keep to themselves.

TS: That’s where your work is different from usual narrative manga. To me, true gekiga means drawing something maybe more philosophical, or more about the philosophy of life and death, something that tries to capture the interior depths of regular people. Some people say your work mimics Tsuge Yoshiharu’s, but I think your work is fundamentally different. You would never see Yoshiharu dealing with the kind of material you do. Even if there are some commonalities, the final product is totally different. Even if your drawing styles are somewhat similar...

TT: There’s no doubt my work resembles my brother’s, but I see myself as doing something different from him. I don’t depict nature very much. I focus mainly on depicting humans themselves. And I do it carefully. I want to observe and drawn different kinds of people.

TS: The expressions on your characters’ faces communicate things that are not in the dialogue. That’s not the realism of actual people, but the realism of your work. In “Manhunt” (“Sōsaku,” May 1969), you might have been dealing with the phenomenon of the “disappearing man” (jōhatsu ningen), and the man’s expressions are similar to those of the men in “Sentimental Melody” and “The Flight of Aogishi.” Nonetheless, you can really feel the “here and now” in that work. I loved how it starts with the strip club.

TT: While drawing “The Flight of Aogishi,” I thought maybe I should stop working with the war. But it’s still connected at some level. It’s like I can’t get away from it...

TS: You probably have a fixed image about what those kind of men are like.

TT: Yeah, probably. I don’t know what’s going through their minds, but when you listen to those men talking in the course of their daily lives, even if their not saying anything significant, I can’t help but hear them saying to themselves, “I hate this, I hate it, I hate it.” Maybe that’s not what they mean at all, but I can’t help but thinking that. I imagine all of them going through life thinking like that. Where does that feeling of hating everything come from?

TS: I hope you stick with these questions to the end. They say it’s not healthy to be obsessed by one thing, but what you are dealing with is precisely the kind of thinking that insisted on irresponsibly continuing the war, and then on irresponsibly changing direction after the war.

****

TS: Do you watch movies?

TT: Not very much these days. But when I was small I did. Like Misora Hibari’s “The Sad Whistle” (“Kanashiki kuchibue,” 1949), I watched that twice a week.

TS: Speaking of “The Sad Whistle,” period pop songs appear often in your work, like “Following a Star” (“Hoshi no nagare ni,” 1947), “The Hills of a Foreign Land” (“Ikoku no oka,” 1949), and “Lil Back from Shanghai” (“Shanhai gaeri no riru,” 1951). People who were kids back then internalized the mood of those songs. Me, for example, I can’t really remember any songs after 1952 or 1953. It’s like postwar music ended around the time of “Lil Back from Shanghai.”

TT: It’s the same with me. Kasuga Hachirō appeared, then Mihashi Michiya and Minami Haruo. But by that point I couldn’t care less.

TS: On TV, there’s that program Sentimental Melody (Natsukashi no merodii). But it’s just not the same thing. Them singing those songs on a fancy stage like that, it makes me mad. It has nothing to do with your “Sentimental Melody.” I almost want to say to them, “That’s not ‘Lil Back from Shanghai!’” It’s not that they used to sing it differently, but rather that it’s wrong to sing it the way they do now...

TT: I look at people from my generation and think, I don’t know how you live, I don't want to know, and I’m not going to ask you. What I usually notice is the loud clothing they parade around in, and the yelling at demonstrations. But reading the newspaper and watching TV news, I don’t feel a thing. I mean, really, not a single thing... I’m not bragging or anything. It’s probably because I’ve had a full-time job my whole life.

TS: For me, a song like “Following a Star” came out of a brutal time of anarchy and chaos, so singing it peace-and-happiness-like is just wrong. I don’t think we live in an age of peace and stability. I don’t think the postwar has really ended yet...

TT: I really don’t get mainstream society, that’s probably why I don’t care about it. I more that I don’t get than I do. On the other hand, I truly understand the kind of people I used to work with. They don’t have to say a thing, and still I understand them. I’m interested in the things the kind of factory workers I used to work with say on a daily basis. They way they talk to one another is entertaining.

TS: Even in “Vincent van Gogh,” there’s that scene with the union meeting.

TT: It’s like that in real life. You might be in a union meeting, but people are just reading the newspaper and having totally unrelated conversations. Everyone might clap after it was over, but no one knew what the speakers were talking about. The president and the chairman would be trying their damnedest, and everyone would be yadda yadda yadda. Then when they asked for our opinion, silence. Only a couple people had any interest in what was going. “Whatever, just hurry up and finish,” some would even say, “What do I care if the company goes bankrupt?” Everyone was dissatisfied on a daily basis. But after bitching out loud a little, they’d move on to talking bullshit.

TS: Is that something you want readers to understand?

TT: I’m not thinking about that when I’m drawing. Probably they won’t get it. I don’t think anyone gets to understand anything through conversation. But that doesn’t bother me.

TS: When you get down to it, reading your work, I get the sense that it ultimately doesn’t matter to you if you drew it or not. Or rather, there’s no point in me the reader thinking too hard about it. Yet it’s precisely because you’ve drawn it that I begin questioning myself about these issues.

TT: Of course, there are other ways of living that are the exact opposite of this back alleyway kind of life. There wasn’t much conversation in the back alleyways, I don’t think. People think of alley talk as silly and meaningless, but not me.

TS: It’s a matter of perspective. Some people see it as silly, some don’t.

TT: There’s something that seeps out of alley talk. But people who see things differently aren’t able to get it.

TS: Are you referring to some kind of existential reality in alley talk?

TT: Yes, it comes out naturally in their words without them thinking about it. People who spend their time reflecting consciously about the world might blab with a purpose, but spontaneous talk also has a weight to it. And that’s what makes it so frightening.

TS: Most people would say that that kind of conversation is simplistic, but it’s not all. Just being alive is complicated, and then on top of that complication one has to make a living. That situation doesn’t get expressed through complicated language. It’s like core of complicated language is filled with simple things.

TT: Yes, I agree.

TS: Or maybe, hiding inside simple language are pains and hardships that are so complicated that they have to be simplified. Would you say it’s easier to express something like that through comics, especially gekiga, rather than through prose writing?

TT: Definitely. Having pictures too allows you to express things more fully.

TS: I think that people are fundamentally the same, whether they live in the Yamanote area [wealthy upper city of Tokyo] or the shitamachi [working class lower city]. There’s no need to separate them. Human existence isn’t something that can be calculated that way. And in that case, all conversation is ultimately alley talk.

TT: Everyone is just living in whatever crazy way they have to. There’s no time to philosophize about it. If someone says, “What the hell is this?” about the way I draw things, there’s nothing I can do about it. I can’t force them to see things my way, just like they can’t force me to see things their way. If you only see the surface and say, “Huh, I had no idea people were like that,” that’s enough for me. You can just flip through and learn that people live different kind of lives without taking away anything deeper than that. You can quickly pass along the surface. That’s how regular life is anyway. We just pass by each other’s lives.