From The Comics Journal #250 (February 2003)

Fast approaching 70, thus well past retirement age, Raymond Briggs keeps meaning to give up writing and drawing his books. Luckily for all of us, he never quite manages it. When I visited him, he was already deep into his next book, for now still under wraps, and discovering the delights and despairs of incorporating computer techniques into his work to produce convincing reflections in puddles. He had just returned from the opening of an exhibition about children’s authors at The National Portrait Gallery and was also set to endure another marathon interviewing session for a bumper celebratory art book about his career, due out next Christmas.

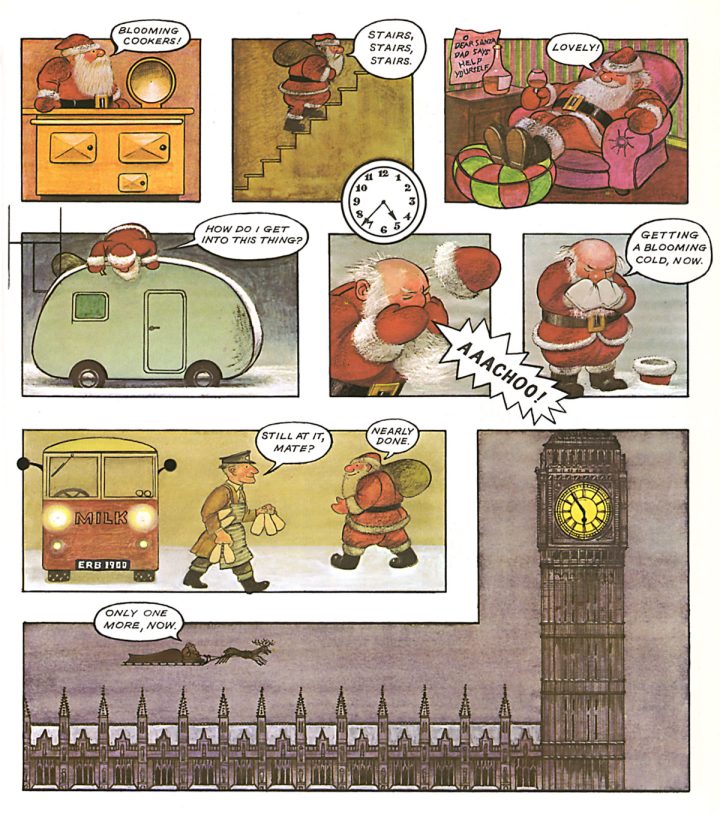

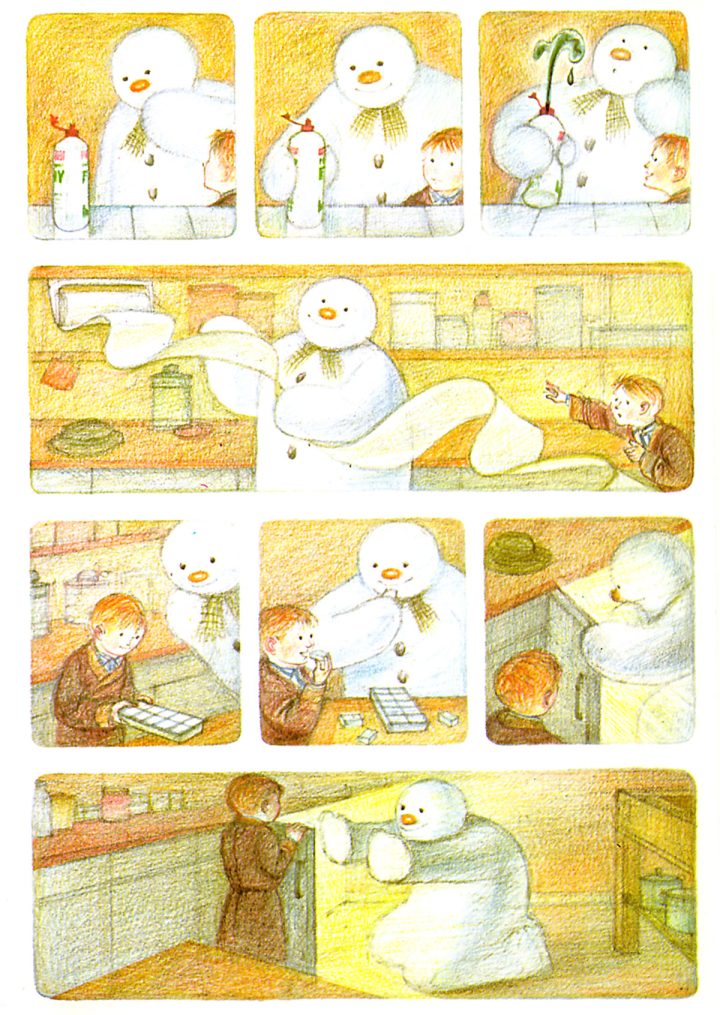

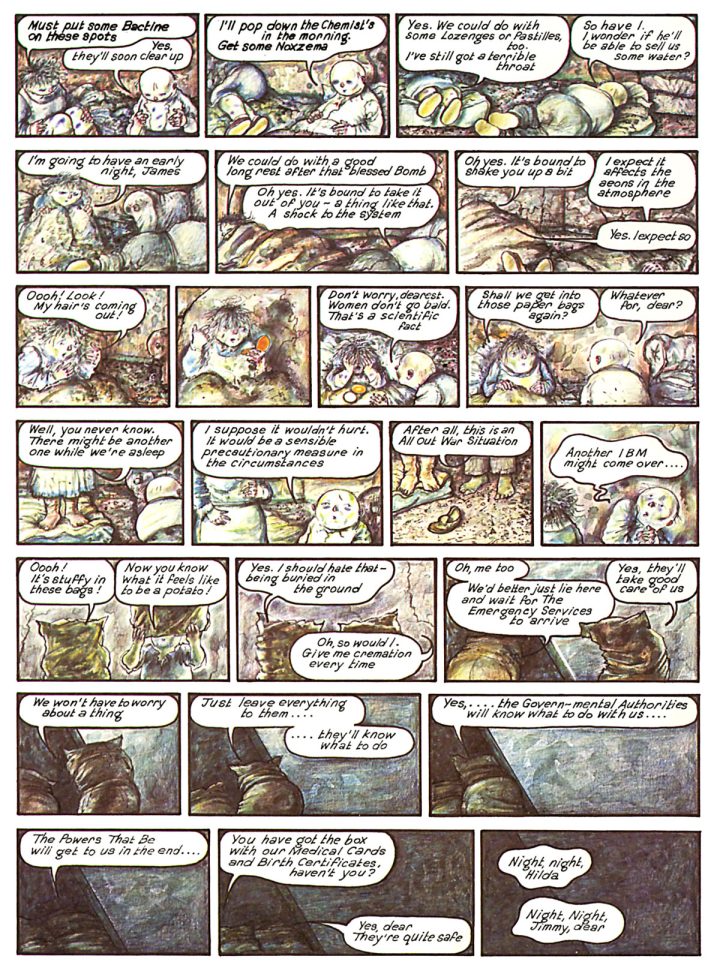

A freelance illustrator since he was 23, Briggs initially made his name drawing color hardcover children’s books, a rarefied and respected genre in which the British have long excelled. His 897 illustrations for The Mother Goose Treasury won him his first Kate Greenaway Medal in 1966. He won his second in 1973 for Father Christmas — again for his illustrations but not his story, a reflection on how judges saw the two as entirely separate. Writing and drawing his grouchy, far from jolly Father Christmas, he adopted the “strip cartoon,” a format he had loved since he was young but which was still not entirely approved of in classier British publishing circles. Precisely because Raymond was not steeped in the clichés and baggage of comics, he developed his own idiosyncratic and powerful approaches. Over the past 30 years of international bestsellers, he has demonstrated the charm and versatility of the medium in such inventive children’s tales as The Snowman, Fungus the Bogeyman, The Bear and his latest, Ug, while also tackling darker and more personal subjects, from the chilling post-nuclear warning When the Wind Blows to the tender biography of his late parents, Ethel and Ernest. His distinctly British body of work is a national treasure and yet has hooked readers worldwide.

In a questionnaire, Raymond once replied that his favorite possession is his home. Visiting his comfortable, two-story cottage deep in the Sussex countryside of southern England, I could see why. He’s lived and worked there for years, first with his wife and after she died, on his own, with no children, no pets, though as a gentleman he maintains his privacy about a lady friend down the road in the next village. I arrive on a perfect English summer’s day, except for the high pollen count aggravating his hay fever, in time for morning coffee out of the “dreaded” Snowman mugs. His kitchen teems with Snowman crockery, oven gloves, tea towels, and there’s still more merchandise from Fungus and Father Christmas filling his bathroom to overflowing. He explains, since he gets sent them, he might as well use them.

He takes me on a guided tour. Upstairs in his roomy studio, he rummages through the heaving bookshelves to show me a particular comic album by Italian porno maestro Guido Crepax and is mildly ruffled and yet deliciously shocked by its creepy, emaciated participants. He gives me a potted tour of the framed originals, none of his own work, crowding his walls. As we return downstairs, he reminds me that Posy Simmonds, the cartoonist and illustrator, his friend and stable-mate at publishers Jonathan Cape, had an awful fall down her stairs some years back and how he really must get a proper banister put in.

In the front room I rifle through his growing collection of quirky headline posters from his local newspaper, such as the priceless promotion “Five Pairs of Shoes To Be Won!” We finally gravitate towards his open-plan living room at the back, looking out onto the garden, and settle down on sofas. Around us are the tidal flows of more books stacked on shelves and in piles on the furniture, including a sort of “shrine” of an alarmingly large number of books with the title “When the Wind Blows” or permutations of it. Later, the conversation continues over a pint and a pub lunch and then in his car dropping me off at the railway station.

The interview took place on May 8, 2002, and was subsequently expanded, edited and revised by both of us.

—Paul Gravett

* * *

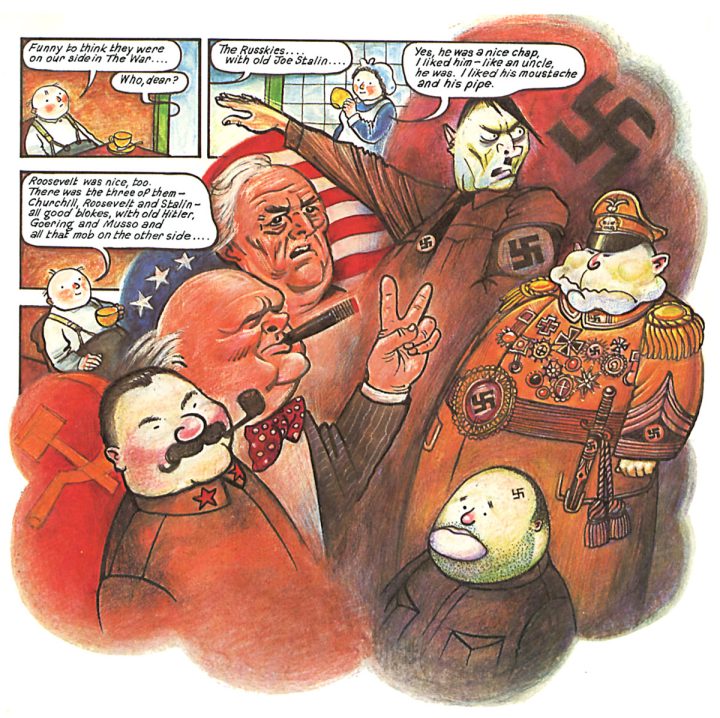

PAUL GRAVETT: You were telling me that you wrote to Carl Giles.

RAYMOND BRIGGS: Yes, I wrote to him when I was doing When the Wind Blows, because I kept drawing Hitler, Mussolini, Goering and whatnot, and as I grew up with his cartoons, all my versions came out looking like his. So I wrote to him to ask, “Would you mind if I virtually used your caricatures?” with an acknowledgement to him underneath. But the Daily Express [Giles’ newspaper publisher] said no, absolutely not. I don’t think he’d have minded. I think he did write back himself and said “Surely you can do your own?” Which I did in the end, but they were heavily influenced by him.

GRAVETT: Very often someone does come up with the best way to caricature a politician or public figure, like Steve Bell doing Maggie Thatcher, and it becomes the way everyone does it.

BRIGGS: That’s right, that’s what I feel about new children’s books illustrating Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows now that it’s in the public domain, because once someone like Ernest Shepard has done Moley and Ratty, you can’t do your own. As soon as you see a Ratty that’s not Shepard’s Ratty, you think, “That’s not him, he’s not like that.” It’s become so defined in your own consciousness. That’s why Giles came through in my work, because I got the first ever Giles Annual when I was a kid, my Aunty Bertha gave me it in 1946. Three shillings and sixpence – now worth 250 quid! [Laughter]

GRAVETT: Actually, after Giles died in 1995, an awful lot of Giles Annuals popped out from people’s attics and the market did slump a bit.

BRIGGS: That was a lovely one. I always remember that cover with the pig in the background in amongst all the bomb damage, sniffing a German helmet. Lovely! And all those generals coming out with a white flag and some tommy watching. Brilliant. He did wonderful landscapes and townscapes. I was 5 when the Second World War began, 10 when it ended, so Giles was the main thing I saw, in political caricature anyway.

GRAVETT: So were your parents Daily Express readers?

BRIGGS: No, no, they weren’t; they had the Labour papers. The Daily Mirror, which used to have all the old British strips, that’s what I liked. They had Garth, the early crude ones drawn by Steve Dowling. And the detective Buck Ryan, Belinda and the Bomb Alley Boys – very like Little Orphan Annie, obviously cribbed from it. Useless Eustace by Jack Greenall on the back was a pocket cartoon. I used to collect those, stuck them in a book – dozens and dozens of them, one every day, more than 300 a year.

GRAVETT: He was a bit of a loser, wasn’t he? Perhaps a distant cousin to some of your characters, like Gentleman Jim?

BRIGGS: Yes, some of my people. I hadn’t thought of that, good point. And Ruggles, he was a bank-clerk type of person with glasses and a mustache, a bit like Frank Dickens’ office underdog Bristow. There was a whole block of strips right down the page in the old Mirror. And there was Jane on a separate page. I wish I kept all these things, but now I’m having a great clearout here, and the stuff you get, particularly when you’re old, you’ve been building up, I’ve been in this house 30-something years. It’s terrible throwing stuff out. I keep putting piles of stuff behind the sofa that’s about to go. And you wander through the room a month later, when you haven’t thrown them out, and look and see “God, I’m not chucking that, fancy putting that out!” it would be fun to see those Useless Eustaces again.

GRAVETT: Part of the problem is that there were so few book collections of this stuff.

BRIGGS: Yes, there were no Eustace or Ruggles books, I don’t think. I’ve got some books with that strip about a little baby in his nappy [diaper], Nipper. That was in the Daily Mail.

GRAVETT: What comics did you read as a youngster?

BRIGGS: There weren’t that many comics when I was a kid, because it was during the War. I had the boys’ story paper The Champion, I took over somebody else’s order, you couldn’t buy new comics; you could only get them on order. I used to read Leader of the Lost Commandos, Rockfist Rogan, RAF and all those. I read Chips a bit, and Rainbow – Roy Wilson is one of my favorites.

GRAVETT: What about The Wizard?

BRIGGS: Oh yes, that was one of the main ones, with Wilson in his black tights. [They wander over to a wall full of framed drawings in the front room.] I wrote to some of these people and got originals. Up there I’ve got a drawing by A. B. Payne of his Pip, Squeak and Wilfred. He sent me that. I still have the soft toy of Wilfred with velvet ears. Limp and filthy, its eyes fallen out and replaced with buttons.

GRAVETT: That was such a popular animal strip in the Mirror. So from early on you were writing to them in 1947? You were keen to make contact with other cartoonists?

BRIGGS: Yes, I wrote to all these people. That was when I was 13. [Sidney] Moon — he was in the Sunday Dispatch – signed to “Master R. Briggs.” I got a Joe Lee, which I lost – he was in the Sunday Evening News. I had an original by Fougasse, alias Kenneth Bird, who was editor of Punch magazine at the time, and an Arthur Ferrier, with his sexy girls with long legs and nylons, that disappeared. That’s a Steve Bell, a 1993 cover for Private Eye. That’s a birthday card he did for me, the Grim Reaper in a Hawaiian shirt. I did my 50th birthday on the theme of a funeral, so everyone had to come as if to a funeral. That’s the best bargain I’ve ever had, a Charles Keene drawing, one shilling and sixpence! It was just put outside a shop in a cardboard box and sold for the frame. I thought, “That’s a nice drawing, I’ll get it anyway” and then I saw “C. K.” and knew it had to be him.

I had always wanted to do cartoons for Punch but I never sent anything. Quentin Blake was sending stuff to Punch when he was 15 and getting it published. And Gerard Hoffnung was doing them when he was even younger, a schoolboy, for Lilliput. I’ve got stacks of Lilliput up there, rows and rows of them.

GRAVETT: Wasn’t that a slightly saucy magazine?

BRIGGS: Oh not half, yes. Nude ladies in it.

GRAVETT: So you tried drawing some joke cartoons?

BRIGGS: Yes, I remember the first one I did: a Channel swimmer and a chap behind in a boat holding an umbrella over the swimmer’s head. Which was supposed to be funny… I was trying to do these ridiculous situation cartoons, no words, just something absolutely absurd in the drawing like that.

I used to hang about outside Arthur Ferrier’s Kensington flat waiting to get his autograph – an extraordinary thing to do! He drew in a magazine called Everybody’s, which was printed in red and black, terribly old-fashioned now. He was a bit like the New Yorker’s Peter Arno; a sophisticated man-about-town in a world of rather naughty nightclubs, posh restaurants and sexy girls.

I once sat next to Osbert Lancaster in a pub once years ago. He looked amazing, in that mustache and tie, and his hair practically permed and his Savile Row suit, walking stick – a real English country gent, incredible. I didn’t meet him, I just happened to be sitting in a pub elbow-to-elbow with him as he was talking to somebody.

ART SCHOOL CONFIDENTIAL

GRAVETT: Osbert Lancaster is acknowledged as the British inventor of the pocket cartoon, in a single newspaper column, with his Maudie Littlehampton. It’s interesting to speculate about the other direction your work could have taken, but you ended up instead in children’s books. What was your next step towards this?

BRIGGS: Going to art school. I left school at 15 to go to Wimbledon Art School. I wanted to learn to draw in order to become a cartoonist, and when I said that to the principal at the interview, he nearly lost his temper and said, “Good God, boy, is that all you want to do?” So the thing to do was to be a fine-art painter. I can actually remember, having gone to art school and got all this culture rammed down my throat, we were told not to get too involved with the coarse vulgarity of everyday life, like magazines and advertising, when we should be studying the Italian Renaissance. I can remember looking at the Daily Mirror and thinking, “Well, a quick look won’t hurt!” As if I was touching pitch or something!

Wimbledon Art School was very old-fashioned then and traditional. I didn’t know at the time, because I knew nothing of other art schools, but I found out later that it was looked upon as a slight joke, totally untouched by modern art. Jolly good training actually, tip-top for an illustrator. The painter Stanley Spencer sent his daughter there, Unity, she was a couple of years ahead of me. So it was very well thought of and there was a huge Spencer influence on the school, so everyone painted corrugated iron, cobblestones and things.

It wasn’t until I got to the Slade School of Fine Art afterwards that I realized that Wimbledon had this reputation. I was showing my work to some friends in the corridor at the Slade just after I’d arrived, I had a few pictures stuck up and these newfound friends were all looking at them and this chap called Schmidt walked past – a fellow student, he became a huge intellectual – and glanced at my pictures. He’d never seen me before. He asked, “They yours?” I said “Yes.” He said “Wimbledon?” Just like that! Jesus Christ! When you’re at the school, you can’t see the wood for the trees. You think all these painters from the school are utterly different, but for an outsider, they were all labeled “Wimbledon.”

We had a joint exhibition, the Slade with the Royal College of Art, and you could stand at the doorway of the gallery and look in and say “Slade,” “Royal College,” “Slade,” as if they’d got labels on them. Royal College was grim; lots of grays, flat blacks and ochres, abstracts. The Slade pictures were much more colorful and happy, totally different. Later, when I was teaching at Brighton, I went to the principal, Robin Plummer, went to his huge office and there were these paintings on the walls and they just screamed “Royal College, 1950s!” They came out all the same, they all think they are different when they’re there. We all did, too.

GRAVETT: Rather than prizing individuality.

BRIGGS: Exactly. At the Slade, the prevalent style was Cézanne-ish, dab-dab-dab. Others were doing flat-edged abstracts or sub-Van-Gogh, totally different things – and yet, as I say, when we had this joint exhibition, you could tell which were the Slade pictures.

There were some eccentric teachers there. One barmy chap used to spend the whole day gazing out of the window, standing at the top of the basement stairs, drinking cups of tea. He hardly ever spoke to anyone, but one day he came into the life-drawing room and sat down next to me. He picked up my rubber [eraser], looked at it and said, “Oh, that’s good isn’t it, where did you get that?” We spent the next five minutes discussing this bloody rubber, then he got up and went away again. Absolutely weird.

GRAVETT: How did your parents feel about you going to the Slade?

BRIGGS: My mum was absolutely horrified. They looked upon artists as dangerous and unable to make any money. Fortunately, it was in the days when you could get grants to go to art school and I managed to get one.

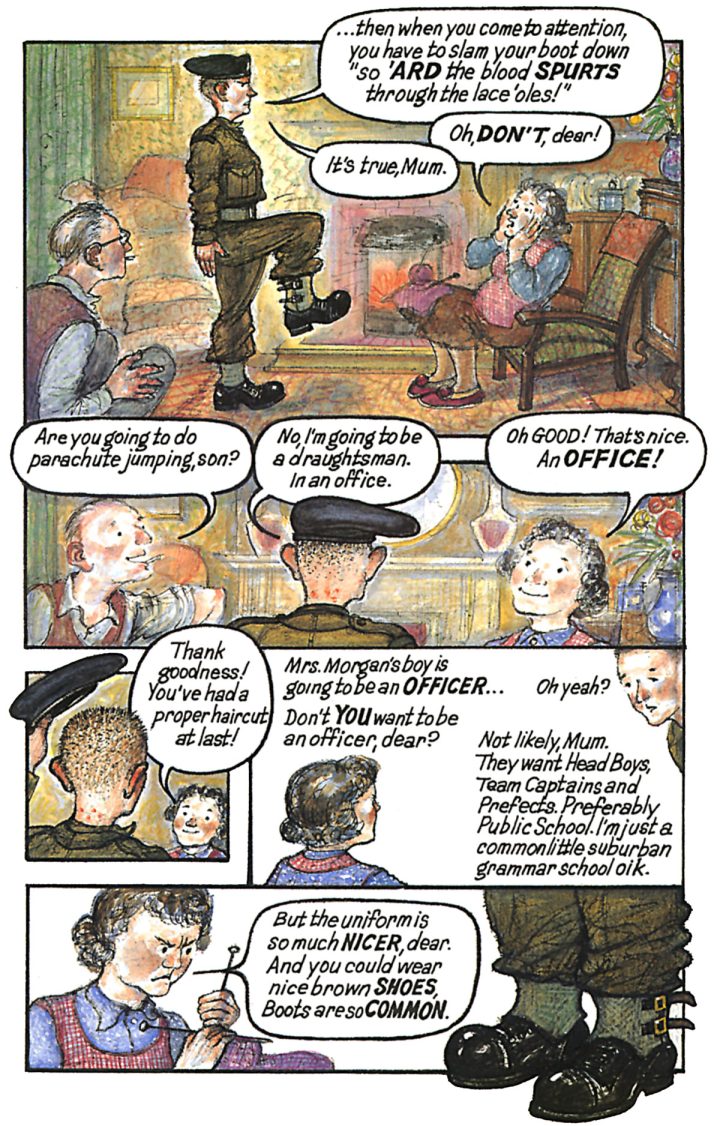

GRAVETT: You didn’t start there, though, until after you’d finished your National Service.

BRIGGS: No, I went into the army for two years and carried on drawing – I was quite a workaholic. l remember coming home from that hellish stint in the army to the warmth and comfort of our little kitchen. Seeing my mum and dad and girlfriend. Carpets on the floor! Curtains! The women in pretty clothes. A cloth on the table. China cups and saucers. A comfortable bed. Food you could eat. And no one shouting at me.

GRAVETT: Had you always loved drawing as a child?

BRIGGS: A bit, I can’t say I was obsessed with it, but English and art were my two favorite subjects at school. Then I tried joke cartoons, but it got diverted into this painting lark.

GRAVETT: Looking back now, do you regret art school?

BRIGGS: A more perceptive teacher would have seen that I was a natural-born illustrator earlier on. If I’d been teaching me, in my wisdom later as a teacher myself, I’d say this kid shouldn’t be painting at all; he’s no good at color, he’s got no feeling for oil paint, what he can do is draw out of his head without reference or looking at anything and create a scene, quite good at line, quite good at tone, and keeps writing all round the edge of the pictures, so he’s a natural writer-cum-illustrator. And he could have been funneled into that a bit earlier, instead of wasting so much time – six years in all at art school – barking up the wrong tree.

GRAVETT: I suppose it was useful training?

BRIGGS: Wimbledon was all based on the Italian Renaissance: two days a week figure composition, two days a week life drawing, one day still life – and figure compositions to do at home, which were illustrations, really – that was the program in the painting class. One day, my tutor at the Slade, professor William Townsend said to me, “You have this extraordinary ability to paint realistic scenes from your imagination without any references.” Now that is the essence of illustrating: to be able to draw from memory, you have to be a mini-actor. If your figure has to be walking jauntily with his nose in the air, you have to imagine what that feels like. I had this ability and it dawned upon me then that illustration is what I should be doing.

That’s the funny thing about illustrating. You’ve got to be in two places at once. Psychologically, it’s quite odd. You’ve got to be the figures. If you’ve got a figure running along in fear, you’ve got to imagine it, you’re sort of acting it in your mind. Yet at the same time, another part of your mind has got to be at whatever viewpoint you’ve decided to look at it from and think, “Oh yes, we’re looking down on his shoulders, that’ll be foreshortened, we won’t see his behind, his thigh will come forward like that, the shin’ll be going down, we’re looking down on the front of the foot, I see the top of his head, his hair will be blowing in the air going past his head.” So, as an illustrator, you’re in these two places at once — in a way, quite an odd psychological feat. Some people don’t do that. They copy a photograph or reference or something, but the proper illustrator I think draws from inside the figure. E. H. Shepard and Quentin Blake and all the best people see the figures from the inside, not merely looked at from the outside. Of course, you’ve got to look from the outside as well, to make sure they’re in the right perspective and everything.

FREELANCE ILLUSTRATOR

GRAVETT: So you never entertained the idea of being a painter?

BRIGGS: No, you couldn’t earn a living unless you were someone like David Hockney. Only a handful of people make their living painting. So I knew I had to do some sort of commercial art, so that meant newspapers, magazines and anything I could get. I used to ring up and ask to make an appointment to show my portfolio. I don’t know if you can still do that these days. In the book world, publishers won’t take unsolicited manuscripts anymore; it has to go through an agent, if you can get one. So it’s just moved the locked door further away from the goal, oh dear!

GRAVETT: Were you still living at home after art school?

BRIGGS: Yes, I lived at home for a year after art school, because I couldn’t afford anything else. Then, when I was 25, I made the dramatic move from Wimbledon Park to… Wimbledon! Tremendous, getting my own room, away from Mum and everything. They didn’t want me to go, of course. I was dying to get away because of the sex point of view; you can’t have girlfriends at home and whatnot. If you’ve got your own room, you can do more or less what you like — if you can get them past the landlady! I must have had enough money coming in by then, the room was only about 30 bob a week [about £33 in 2022 money]. In fact I offered her more, so she said “Two pounds then.” For a nice big room at the top of this house on Wimbledon Common, bloody marvelous. Literally 50 yards from the edge of the Common. Very posh area.

GRAVETT: How did your freelancing go? Did you get some regular accounts?

BRIGGS: No, it was pretty erratic, whatever came in. The first thing was in House and Garden magazine — “How Deep To Plant Your Bulbs,” a diagram of five horizontal lines and these hyacinths, daffodils and whatnot. Got eight guineas for that, which I thought was fantastic, it only took about half an hour. I did some advertising — DIY catalogs, cake-mix packets. I didn’t like advertising, I hated the people, I hated the nature of the work. Terrifically well paid. The subject matter they give you to do is just awful; it’s the antithesis of story. They say they want a woman washing up at a sink, but don’t make her too old, don’t make her too young, don’t make her too upper-class, nor too working-class. It’s impossible. They want it to appeal to Mrs. Everyman or Everywoman, who doesn’t exist, and it knocks all the character out of it. The whole fun if you’re doing a book illustration is to have this old lady at the sink, or some glamour girl, but they’d iron all that out of it and ruin the whole point. But I did magazine illustration, for Radio Times and others.

GRAVETT: Editorial illustration could be a very lucrative field, before photography took over, wasn’t it?

BRIGGS: Yes, I was saying to my partner Liz last night, while looking through this article on Tom Waits in the Sunday Times Magazine, that, “Do you realize in this whole magazine, about 100 pages, I can find two illustrations in it.” In the '50s, every little small ad would have a drawing, endless work. Now, there’s virtually nothing of that sort.

GRAVETT: I think that’s partly because it’s so much easier for editors and designers to deal with photographs, and they haven’t been raised with any illustration background, or any taste for it.

BRIGGS: Yes, and they’ve got image banks now too, they can get something off the internet. It’s all ready for reproduction. It’s cheaper too, because if you give an illustrator the job, he might go and get the flu or he brings it in and it’s not right. Whereas they can get it readymade in the fraction of the time and cost. And book jacket illustration is another thing that’s virtually disappeared. There are almost no illustrated book jackets these days — if you look at that lot there, there’s hardly a single illustration on any them. They’re all photographic.

GRAVETT: Illustration is starting to disappear out of people’s everyday lives. I worry that people are losing any appreciation for drawing, for lines on paper. Drawing is very odd and individual and eccentric, it’s not the easy, anonymous blankness of so much photography.

BRIGGS: Janet Woolley used to paint these huge heads with tiny bodies, portraits for Radio Times. But now – I thought they were photographs at first, that some photographer was copying her – instead of painting these huge-head portraits, she’s obviously feeding in a photograph and putting them on a little painted body. So it looks 90% photographic and it’s lost a lot of the feeling that they had.

When I left teaching at Brighton in 1987, the computer hadn’t really struck yet. But I’m told now, when you go to the Brighton Degree Show – which I missed this year – you can’t tell what department you’re in. It used to be fine art, illustration, graphic design, textiles, pottery, sculpture and so on. Now all the “painters” are making films, sculptors are doing installations or working on light shows, illustrators are working on computers making “semi-films.” You honestly don’t know where you are.

CHILDREN’S BOOKS

GRAVETT: So in a sense, your books may be some of the only illustration some people ever own or are aware of.

BRIGGS: Yes. Children’s books are the main field for illustrators in Britain at the moment. Having tried magazine, newspaper, and advertising illustration, I looked into book illustration, but I discovered that meant children’s books. I thought, “Yuk!” However, I soon realized children’s books were wonderful to illustrate because, although it was the least well-paid, at least the subject matter was inspiring. I realized that the best thing for an illustrator to do is the picture book, because you’ve got color. So I tended to do that more and more.

GRAVETT: You won the prestigious Kate Greenaway [Medal] in 1966 for your nearly 900 illustrations in your fourth children’s book, The Mother Goose Treasury. You were illustrating other people’s texts then?

BRIGGS: That’s right. Then I realized the best thing is to write your own, because otherwise you’re sharing the rewards with a writer. So if you do the whole thing yourself, you get double the pay and it’s more satisfying, if you can do it. And some of the stuff I was given to illustrate was so dreadful, I thought I can do better myself.

GRAVETT: Had you grown up on the classic British children’s books? Had you always been a great admirer of children’s book illustration? Did you know about the tradition you were coming out from?

BRIGGS: No, not at all. I tried to avoid looking at it when I started taking it up too, because I thought I don’t want to be influenced by other people. I didn’t read The Wind in the Willows till I was about 40 or so, and Alice in Wonderland until about the same age. I tried to avoid reading them or even looking at them, which is a bit daft. I wrote lots of little books first, before I did the first strip one in 1973, Father Christmas.

GRAVETT: Was there any resistance from the publishers to doing the strip-cartoon format?

BRIGGS: No, but I needed far more pictures. These books are only 32 pages, usually – occasionally 40 – with only a couple of pictures on each page. I knew I needed more pictures to tell this story, so it turned into a strip cartoon just for the spatial demands of it.

FATHER CHRISTMAS

GRAVETT: Your Father Christmas didn’t conform to the jolly icon we all know.

BRIGGS: I just thought, “Follow it through logically: He’s an old man, we know that, he’s fat and he’s been doing it for donkey’s years, so he’s fed up with it.” It’s a vile job anyway, out in the freezing cold, on your own, going up and down filthy chimneys. You can’t imagine a worse job, really, going through the cold air, all over the world. And he never gets any thanks; they just put out a mince pie! It’s wonderful that kids still do that. Liz’s grandchildren are absolutely thrilled. They put out some carrots for the reindeer and half a bottle of beer for him, and they wake up and shout, “Look, he’s been here! They’ve eaten the carrots!” They’re terribly excited, absolutely wonderful.

GRAVETT: Did you ever do anything like that?

BRIGGS: No, I don’t think we put anything out for him.

GRAVETT: But we’ve all believed for a little while, and then we go on pretending to.

BRIGGS: Oh, yes. Connie has got to that stage now. She’s 8, and keeps it up for the sake of the other two, who are younger. I remember my mum saying, “When you’ve finished your dinner, show your plate up the chimney,” to show Father Christmas I’d been a good boy and eaten up all my dinner. Which is extraordinary, because I remember thinking not long after, “Well he wouldn’t be there now, would he!”

GRAVETT: I understand that while you were working on Father Christmas, your wife Jean was critically ill.

BRIGGS: Yes, Jean was in hospital while I was doing the book. I took things in to show her. On Christmas Eve in 1972, Jean was taken ill with this huge swelling that had come up all over one side overnight. We were frightened to death. She hadn’t seemed ill, although her hair was dull. She died of leukemia, possibly brought on by all the anti-schizophrenia drugs she was taking.

GRAVETT: You had met your wife at art school?

BRIGGS: Yes, Jean was an artist too. She was a schizophrenic. I knew about her illness when we married, but we were in love and you can’t not love somebody because they are a schizophrenic. My mum had elements of jealousy about her and she worried that I wouldn’t be looked over properly. But of course with Jean and her schizophrenia, how could I be? She was in another world anyway. It was bad enough for her to go in and out of the loony bin the whole time. She didn’t start doing anything like Mum would have wanted, like making curtains.

I remember when we first moved in here, Jean spoke to the people next door, very conventional farming people. Mrs. Thomas asks her, “And what day is your baking day then?” Jean just says, “What?” Jean was a painter. She exhibited at various galleries, but she didn’t do a job. Her moods were not always so great. You never knew what you were about to face. There’d be agoraphobia, claustrophobia, paranoia. But schizophrenia can have its positive side. She was also very emotional and very inspired and inspirational.

GRAVETT: You never had children?

BRIGGS: No, it’s not very good for schizophrenics to have children, but you’re always hoping it will get better or go away. I didn’t mind not having them. We did start one off by accident, got all interested in looking at prams and then she had a miscarriage.

GRAVETT: I know Christmas has another sad association for you.

BRIGGS: Yes, my mum died at Christmas in 1971, probably of cancer. They’d never tell working-class people what’s wrong with them. They’d just say “We’re going to do some tests.” Years before, she had some kidney problems. We got a phone call from the hospital saying she was fighting for her life. By the time she got there, she was dead and she was dumped in some spare room on a trolley next to a packet of Vim cleaner. It took me a long time to draw that sequence in Ethel and Ernest. Dad died nine months after her from stomach cancer. Obviously he didn’t want to go on without her. He didn’t have the will to live, making tea [i.e. dinner] for one. Until the end, he’d still set the table for two.

GRAVETT: With such sad associations with Christmas, even so Christmas has been an important element in your stories?

BRIGGS: Well, the Father Christmas book doesn’t say Christmas is all that wonderful, does it? It’s stressing the workaday side of it. That was what interested me. It doesn’t romanticize Christmas. My Father Christmas goes back to my dad. Christmas was his most hectic day of the year, as he had to complete his milk round in time for the family lunch. By the time he got back, the house would be full of uncles, aunts and cousins, while my mum would be cooking the turkey in her tiny kitchen. He’d come in around 1 p.m., 1:30 p.m., with hands as black as a coal miner’s and wash at the kitchen sink among all the food. The bathroom was too good to get dirty. After lunch, we’d play cards and board games. I remember a horse-race game played on a strip or cloth strapped to the dining-room table. Turning the handle would make the cloth vibrate and the model horses would make a hesitant gallop across the felt. Absolutely wonderful, no electricity involved, just the vibration of this cloth. One came up for auction in Lewes recently and I tried to buy it, but it went for over 50 quid and I wasn’t prepared to pay that much.

GRAVETT: How did you find adjusting from children’s books to comics?

BRIGGS: I think you find a size you want to work to and that gives you four rows per page, and you think what you’re going to show on each page. Each page is a little chapter, really. You have to turn over the page and have something else happening; you can’t have scenes trailing from one page over to the next. I was aware of Tintin, for example, but I got interested in strip cartoons after that rather than before it. Father Christmas did really well, appeared in 16 or more languages and won another Kate Greenaway award. I did a sequel in 1975 called Father Christmas Goes on Holiday.

BOGEYMAN, SNOWMAN, GENTLEMAN

GRAVETT: On the recent BBC television series Reading the Decades [2002], they chose Fungus the Bogeyman from 1977 as one of the defining British bestsellers of the '70s.

BRIGGS: They put that book in because it was supposedly sensational and new at the time; horrible humor. It wouldn’t have been published earlier; that was the point they were making.

GRAVETT: There’s a strong tradition in British children’s comics of grotesquerie, like Ken Reid’s Jonah or The Nervs.

BRIGGS: Oh yes, but this was in a children’s book, so it was a bit different.

GRAVETT: You have Roald Dahl’s darkness too, but Fungus brought in more snot, vomit. And toilet humor –

BRIGGS: No. I was writing to the people making the Fungus the Bogeyman film last night. There’s no toilet or lavatorial humor in it. They start off this proposed film script with the sound of a raspberry, which I said is not a good idea, although it’s only his alarm clock. But it gives the wrong tone. They’ve been doing this film treatment for seven years and it’s at last coming together, they think.

GRAVETT: You’ve talked before about Bob Hoskins playing the lead.

BRIGGS: He always wanted to, he’d have been wonderful. He said “That’s me, that’s the story of my life, that book.” Fungus was going to be a stage musical directed by Richard Eyre and a 20th Century Fox musical film. But they fizzled out. Then another man wanted to put on a stage musical as a route to doing a film. And a young composer I met wanted to write an opera about it. It was going to be 13 half-hours for television, but the last I heard it’s now a three-part thing – three one-hours, I think – for BBC4.

GRAVETT: I think it would have worked brilliantly as a film.

BRIGGS: Yes, if it was done like Shrek. A friend in America said he thinks Shrek is influenced by Fungus. He’s got a similar face.

GRAVETT: It does come from a William Steig book.

BRIGGS: Oh, does it? Good God! One of the first books I ever bought was a wonderful little cartoon book by Steig, all on the theme of children.

GRAVETT: How did Fungus evolve as a book?

BRIGGS: I was going to do an alphabet of revolting things, but that seemed a bit feeble, so I created Fungus. I was anxious to avoid sick humor and keep it funny-disgusting. The point about Fungus is that, like all of us, he wonders what he’s alive for. It’s about the search for a role. I said to the editor, “You’re not going to like and you’re almost certainly not going to publish it!” I was amazed how easily they accepted it, apart from a few things cut out with those black panels.

GRAVETT: So those “censored” panels were actually drawn and then covered over? Like the panel of Fungus’ toilet?

BRIGGS: No, the toilet was a genuine one. I didn’t want to draw that! I covered it over and that gave me the idea, when the editor wanted other alterations, to do the same and save the bother of re-drawing it. And it made it look worse, because if you cover something up, you make it look more obscene! Fungus has been in print 25 years this year, which is good. I think kids like Fungus because it’s messy and naughty and it smells; it’s the inversion of the everyday world. And it was my declaration of war against the tyranny of spinster librarians deciding what children were allowed to read.

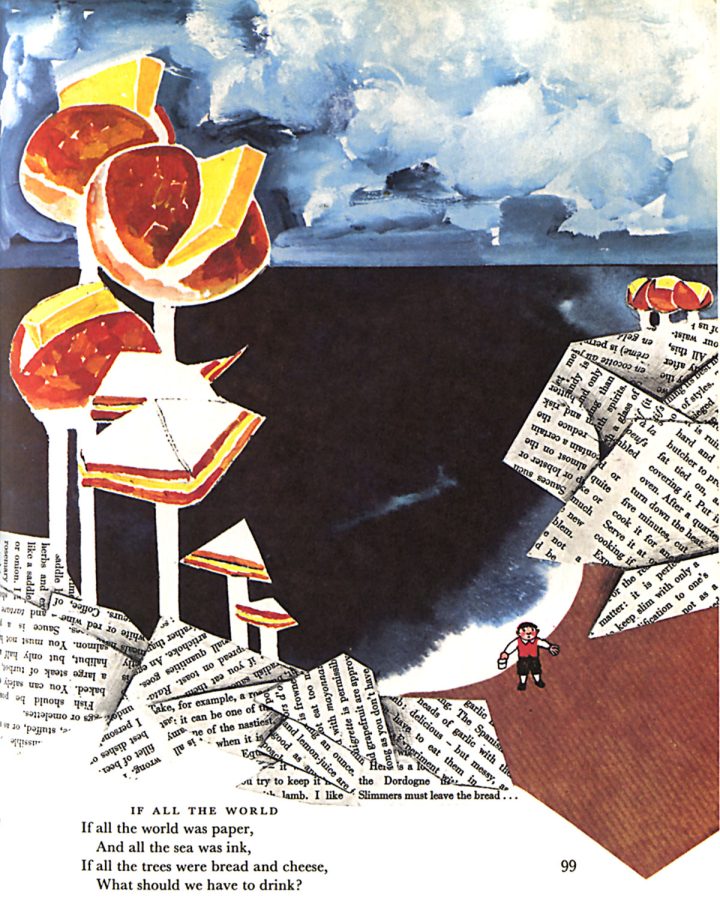

GRAVETT: After the wildness of Fungus, some people felt The Snowman was rather sentimental.

BRIGGS: I just wanted a nice, easy quick story without words after doing Fungus, which was so long, involved and tedious and concerned with muck and slime. And there are no lovey-dovey scenes in The Snowman, are there? Apart from in the cartoon film, when the boy kneels down at the end and finds the melted snow. The Snowman came from a comic I’d had years before with snowmen coming to life. It stuck in my mind as a good theme to pinch. I drew it with pencil crayons, with no line in pen or pencil and no washes of ink or watercolor.

GRAVETT: Your next book, Gentleman Jim in 1980, introduced Jim and Hilda Bloggs.

BRIGGS: I based them on my parents. Not so much my father, really, but my mum was very much one for not thinking and getting on with the dusting, never challenging authority.

GRAVETT: It’s a very funny and touching story. I was surprised to discover that Gentleman Jim is not still in print.

BRIGGS: No, they make things go out of print very quickly nowadays. Only the big ones — Fungus, Father Christmas, The Snowman — are still going on. When the Wind Blows is still around, only in paperback now. It’s this ridiculous situation in publishing where the publisher thinks, “How many are we going to print of these — 5,000, 50,000, 100,000?” It’s pure guesswork. They invest vast amounts of money, they think “This is going to be a big one,” and then they get left with thousands of remainders that they’ve lost money on. They’ve got to pay for storage, the books are physically moved around the country by a series of lorries going through the night, all very expensive. One idea is that the technology is in place to “print on demand”; you’ll go to the equivalent of a bookshop and say “I want the new so-and-so,” and it’s printed there and then at your end. Not in electronic form, but on paper. So you sell and produce on demand instead of the nonsense we have now. I had to buy up some Snowman books in a remainder shop in Lewes. I said, “This isn’t remaindered,” and he said, “No, no, technically, they’re returns,” which means they’ve gone out to the bookshop, not sold and been returned, and they’re not allowed to sell it as new if it’s gone out and back. They’re spotless, nothing wrong with them. And I said, “Well, I can’t have these lying about. It’s bad for the image! Not only that, people will go down the road and buy it full price — £10, £15 — then come in here and see it’s £4.50 and they’ll be annoyed.” So I bought the lot, about 20 of them. He gave me a special deal. Just to get them out of the shop. But it’s a ridiculous system. It’s so annoying.

WHEN THE WIND BLOWS

GRAVETT: In Gentleman Jim, the Bloggs come up against the forces of law and society. What gave you the idea of involving them in a nuclear war in When the Wind Blows in 1982?

BRIGGS: I was watching a Panorama documentary on TV about nuclear-contingency planning. It affected me strongly and I thought, “Here’s my next book.” I wanted to see if a nuclear attack does happen, what do people actually do? I felt very strongly about government propaganda. The authorities were playing it down, pretending it’s like the Second World War, when it jolly well wasn’t. I wanted people to know what’s involved, then they could make up their minds.

GRAVETT: I believe you felt that the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament was a bit simplistic, but you did join, didn’t you?

BRIGGS: Yes. It’s still simplistic but it’s the only thing to do; anything else is total insanity. CND might not get anywhere, but the alternative is even crazier; going on having more and more weapons when we can already blow each other to bits 20 times over.

GRAVETT: Do you think your book helped make the public more aware of the issue?

BRIGGS: Yes, judging from the letters I’ve had, saying they’d never thought about it before.

GRAVETT: Was that your intention?

BRIGGS: I just wanted to visualize the situation as totally real. It’s the same principle as with Fungus, Father Christmas, The Snowman, situations that are imaginary, or in the case of When the Wind Blows, all too real. Most of my ideas seem to be based on a simple premise: Let’s assume that something imaginary is wholly real and then proceed logically from there. What are you and I going to do when we hear the announcement, “They’re on their way!?”

GRAVETT: At least the Bloggs have got their government leaflets! Everyone will be referring to their copies of your book to see what to do! When the Wind Blows was also a very successful radio play. Were you worried that people hearing the warnings of a nuclear attack over the radio, might think it was real and panic? Like Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds broadcast in 1938?

BRIGGS: Yes, I had to re-write it. Hearing Brian Perkins — the Radio 4 announcer, the voice of the BBC — in the studio making the announcement was chilling. His voice gave it such authority, I had to have Hilda Bloggs hum over it so that listeners would realize it wasn’t the real thing.

GRAVETT: When the Wind Blows was the book that really turned your reputation around. Previous to that, you had been purely a children’s book illustrator. Was it hard to persuade your publishers to let you tackle this much darker subject matter?

BRIGGS: No, I don’t remember any resistance to it.

GRAVETT: But the book did stir up some controversy and was even discussed in Parliament.

BRIGGS: Yes, they sent copies to all the House of Commons, House of Lords as well. There must have been some outrage. Lady Olga Maitland was incensed and said it was CND propaganda. There were demonstrations outside the Whitehall Theatre, 50 yards from Downing Street, when I did a play of it as well. They’d either hired, or their headquarters happened to be opposite, I don’t know — but they hung banners, bunting, Union Jack flags and loudspeakers playing “Land of Hope and Glory.” I was heavily involved with the play. I wrote the thing. They did the production extremely well, the explosion and the collapse of the house were superbly done. Laser lights and everything, But there was no development, just these two people wandering around the stage dying and then they die. So there’s no conflict as such.

GRAVETT: But why does that low-key, set-bound story work in a comic and not as a play?

BRIGGS: You need more action, more conflict in a play, and people coming on and going off. There were only two characters and it got a bit tedious, really. The sound was so good, one of the loudspeakers, when we had it in Bristol, caught fire! Flames coming out of it! The fire service went nearly mad down there. And the safety people talking about the lasers and how they might damage people’s eyes.

GRAVETT: All the pyrotechnics of the theater and all the whiz-bang spectacle of animation are just what you don’t get with the comic. It’s very modest, just pen on paper, and the reader has to put the work in of getting involved. There’s a gap left for the reader in comics!

BRIGGS: Yes, I like that, but you can’t think about how the reader is going to interpret it; you just get on and do it.

GRAVETT: How do you tend to work on your stories?

BRIGGS: When I’ve sorted out my ideas for a book, I do a rough in pencil to show the publishers. That’s the nice part. The worst part is planning the space. I hand-letter all the text, then cut it up and put it down — for example, on 20 layout boards for 40 pages — to see how much room it takes up and how much is left for the pictures. With When the Wind Blows, I kept having more ideas and having to re-design the layout. To add four frames meant re-arranging all the others, making them a bit smaller. When it’s all planned, I work on each double spread. I pencil in the outlines, ink in the lines, do the lettering using a magnifying glass, and coloring with watercolors and crayons. It can be two years after the original idea that I give the publishers the final artwork for the printers to print from.

Once I kept a record of the time it took to do two pages of When the Wind Blows: penciling 20 hours, inking 18 hours, coloring 25 hours. And all that is after months and months of getting ideas, writing and planning. I always get fed up with how long it takes me. It exasperates me because it’s laborious, slaving away at the age I am. What I hate more than anything is the fiddly detail of getting all the lettering right and doing separations, doing overlays. These days, publishers try to get you to do all the lettering on overlays, bur I refuse to do it as long as it’s on a white background. If it’s on a color, you have to do it to stop it going through onto all the other places. The work might not look like much once it’s inside a book. But when you put it all out on a wall and it covers the whole end of your studio and if you’ve written it yourself, there are hundreds of words. Even when I’m illustrating the Bert children’s books written by Allan Ahlberg, I counted 54 little paintings. I had to draw the same bloody figure about 50 times. I know that’s nothing compared with animation, but it is rather repetitive and gets me down. I’m getting old and grumpy as usual! It’s very lucky to be able to do this kind of work and go on doing it at this age, really. But I do find it increasingly laborious.

GRAVETT: Do you work up, on a bigger scale, or same size?

BRIGGS: I always draw same-size. To do them bigger would be even more laborious. Though if you do them bigger and reduce them, it looks better. Makes it look better than it is. The Swiss had done a miniature edition of Father Christmas, with little tiny pictures. And I thought it was fantastic. The pictures could go down to about a quarter of its original size by being photographically reduced. And it looked so much better in every way, sharpened up. I hadn’t realized you could do frames that were about two inches by one. So when I came to do When the Wind Blows, I thought I’d use a big format and tiny little pictures, because there was so much I wanted to get in. So that worked well. You don’t need to do frames that big, you could do frames much smaller.

GRAVETT: Did you read Keiji Nakazawa’s Barefoot Gen, about the bombing of Hiroshima?

BRIGGS: Yes. I’m in two minds about Gen. Its heart is in the right place, but it’s so vulgarly drawn, everyone’s got their mouth wide open on every page. But how can you be harshly critical? I think when you’re dealing with nuclear war, you tend to go in one of two ways. Either you treat the horror symbolically — in which case it tends to turn into art or fairy story — or you treat the horror realistically, as in Gen where he has people walking about with spikes of glass sticking out like Jack Frost, and you think, “This looks ridiculous.” You know these terrible things happened, but they’re so horrific that you can’t portray them. It becomes pantomime and that approach leads straight to the horror comic. It’s so horrific, it becomes comical. Suggestion is so much more powerful.

ADAPTING TO ANIMATION

GRAVETT: How involved were you with the When the Wind Blows animated movie?

BRIGGS: Not much, I think. I thought it was OK. It wasn’t what I imagined and there were some daft things in it. It was a huge task; an hour and half of drawn animation. Quite incredible, really.

GRAVETT: How do you feel about adaptations of your books?

BRIGGS: I don’t like developments of my own things much.

GRAVETT: You’ve’ been involved with all of them, haven’t you, to varying degrees?

BRIGGS: Yes. Last year, I wrote the script for this animated half-hour story for Channel 4 TV, Ivor the Invisible. I’m never doing it again, because you can’t get what you want. And it wasn’t a very good idea anyway.

GRAVETT: I gather you’d thought about it originally as a book?

BRIGGS: Yes, and then I realized it didn’t work. But they wanted to make it into a film. And then they go and produce a book based on the film! Which works even less! Oh, Christ! Based on stills from the film, bash out a book in a few weeks. Madness. The art director of the film selected loads of “grabs” from the film, punts this round to Channel 4 Books and a designer there has to go through 600 of these things and draw up a grid, terrible job. I wasn’t involved in that at all. It’s all done at incredible speed. The film was hardly out before they were doing a book of it, all tied in together. While the film’s “hot,” you want to get the book out. I’m not doing that again. With a book, you’ve got the script, the pictures and the design of the book. That’s quite enough to deal with for one person and you can have control of the whole thing. When you do a film, you’ve got the script, the drawings, the design or editing, but you’ve then got sound, voices, music and movement, all these elements. No one can control all these, unless you’re a top director like Spielberg or somebody and you’ve got the brain to do that. And if you do ask for a certain thing, they usually say, “Oh, we can’t do that, it’s too expensive.”

GRAVETT: Your books merely become the inspiration, they’re what these films are based on…

BRIGGS, Yes, and then they take off into their thing and it’s sometimes not quite right. These directors give a nod to the book and then, “Forget about that, now we’re going to make our film!”

GRAVETT: You weren’t as unhappy with The Snowman cartoon?

BRIGGS: No, The Snowman was good. I’m not running that down at all. That was a superb film, superb music, nothing wrong with it at all. And, as I’ve said to everybody, I don’t claim any credit for that; anything that’s in the film that’s not in the book is not me. I was even against their visiting Father Christmas because I thought that was a bit corny, bur it works perfectly well.

GRAVETT: So how is the Fungus project looking to you now? Do they understand the book?

BRIGGS: Yes, they’ve got the feeling of it, up to a point. It’s difficult — I haven’t seen anything visual; I’ve just been reading scripts over the weekend. I’m not sure what it’s going to be technically. First they tried animation, then they’ve been working with animatronics over the last five or six years. But the whole technology is moving so fast that, as soon as you’ve done two years’ work on animatronics, CGI has now come in, which has surpassed anything you could do with animatronics. Then they’ve switched countries, from America to Canada and now England. I’ve got a wad of stuff about it all. I’m going to try to be as involved as little as possible, actually, because it’s very frustrating. That’s what Philip Pullman has said. They’re doing his Dark Trilogy books and he’s going to have absolutely nothing to do with it. For one thing, it takes up a terrific amount of time, and is ultimately frustrating.

GRAVETT: At least with your books you have virtually complete control. Do you get much editorial feedback?

BRIGGS: Not much. They’re very helpful, editors, but that comes in more or less at the end. They say “This goes on too long, cut it,” or “This is repetitive.”

GRAVETT: So you don’t mind some constructive editorial to-and-fro.

BRIGGS: No, that’s just one person, not a whole committee. We had meetings at Channel 4 with 13 people ‘round the table. Two or three people have wanted to do my Ug book as a film and I’ve said no to that, because even if you’re not writing it, there are still endless meetings. “Can you come up to the audition and see what you think?” I’ve said no to a film of Ethel and Ernest and no to a film of Ug at the moment. It’s so time consuming. They say, “Oh, but you’re not writing it or designing it.” But there’s always something. They’re talking about me meeting the Fungus people, bound to do that sooner or later. It’s difficult to strike a balance.

GRAVETT: What made you begin a new collaboration with children’s author Allan Ahlberg, illustrating his Bert books, after years of writing your own stories?

BRIGGS: I hadn’t been asked to illustrate anything in ages, but I liked his story so much, I agreed straight away. I had the idea of putting in these big pretentious chapter headings. I wanted them even bigger so it would look even more ridiculous. But the publishers said no. I wanted to do them as tiny books — six inches by four inches — and if we did four or six of them, we could put them all in a box set and call it “Bert’s Box!” But the marketing people said that small books don’t sell. I said “What about Beatrix Potter, Thomas the Tank Engine, the Mister Men?” The idea that small books don’t sell — where have they been for the last half-century? Crazy!

What gets me is that the people I’m working for weren’t born when I started this lark. The editor and designer — very nice, nothing wrong with them — they’re glamorous young women, scarcely 30, and I thought the other day that, when I won the Kate Greenaway Medal in 1966, they weren’t even born. They’d have been about 3 when my Father Christmas came out. Probably had it as little girls. Not that I’m running them down, but it was a shock working with people you could be the father of.

ETHEL AND ERNEST AND RAYMOND

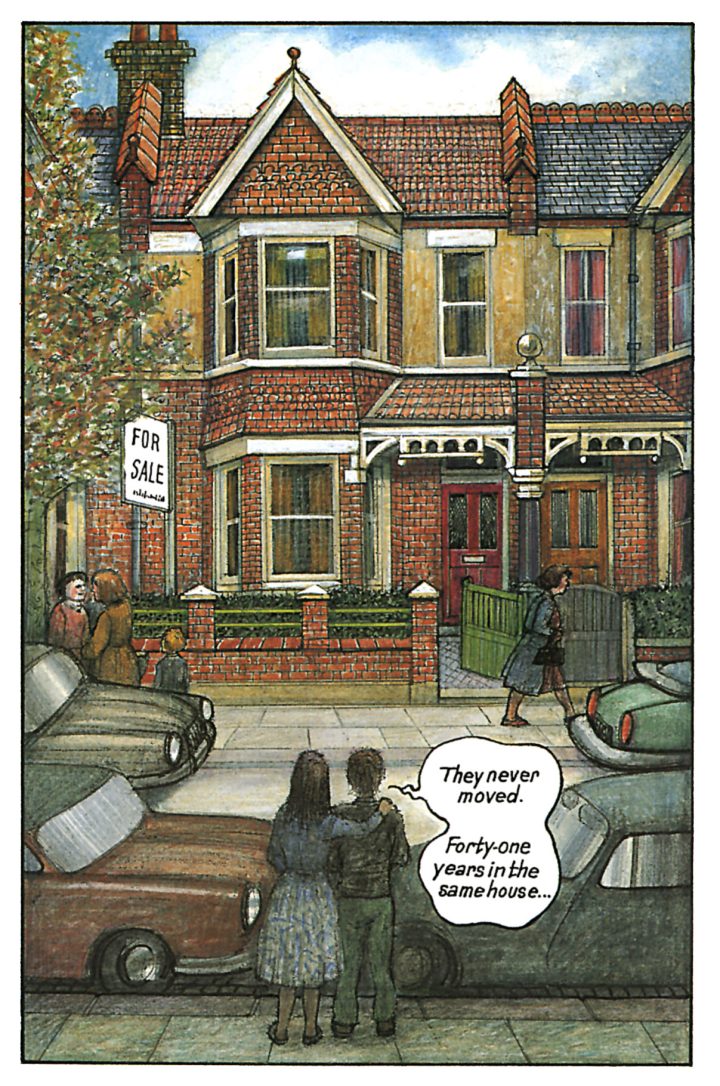

GRAVETT: Your parents have been the models or inspirations for several of your books, but in Ethel and Ernest in 1998 you told their own real story.

BRIGGS: Yes. My father was a milkman, my mother worked as a lady’s maid and, after they married, as an office clerk. They lived in the same terraced house, in Wimbledon Park in South London, for 40 years. They never once went abroad. Only after they retired, they did go to the Channel Islands once and they were completely amazed.

GRAVETT: The book opens with how they first met.

BRIGGS: Yes, that’s how it happened. Mum was shaking a duster from the window when Dad was cycling past. The timing was so exact, one more tabletop and he’d have been gone. She was 34 and “on the shelf”; very late to get married back in those days. But she caught his eye and he stopped. The following day, she was on the lookout for him and this went on for a couple of days, until he called round with a bunch of flowers for her. It must have been embarrassing, because he didn’t know her name, so he wouldn’t have known who to ask for.

GRAVETT: I noticed that you’d done a circular painting of them both on this cabinet door, of your mum knitting while your dad watches the telly.

BRIGGS: Back in my art-school days, I persuaded them to sit for me so I could practice my portrait painting.

GRAVETT: And you were telling me about this China jug.

BRIGGS: Mum used it to store the bills — always paid on time, of course. How did they manage without a bank account? I’ve got a whole drawer upstairs for my domestic paperwork. But they never seemed to have anything; just the cash from my father’s wages, which he would hand over to Mum every week. They simply trudged along, like everyone did in those days.

GRAVETT: Did they love each other?

BRIGGS: Yes, I’m sure they were happy together, if you can be happy. Dad used to bring her flowers every week. The sad thing I suspect is that he loved her more than the other way around. Mum always wanted Dad to be somebody better. She was always nagging him to get promotions. More refined, more middle-class. But he loved his milk round and didn’t want to sit in a tin office. She was always telling Dad off for waving his spoon about in the air. He used to tap-dance on a patch of lino in the kitchen in his hobnail boots. He was terribly loud and heavy. He probably shouldn’t have done it. She would have had more respect for him if he had got a white-collar job. If she could have married a bank clerk, she would have done so. Before Dad, she went out with a deep-sea diver — more prospects there.

GRAVETT: Dare I say, from the book your mother comes across as a bit of a working-class Tory snob.

BRIGGS: I think she picked up her airs from the house she used to work in. Working with posh people, she discovered side plates and fish knives. She was very ladylike, and rather sexually naïve. She would have considered sex an “unladylike” thing to contend with. She lived an incredibly protected life. When she was young, she ran home from school screaming in terror, because of this blood that she didn’t know was her first period.

GRAVETT: What was your relationship like with your mother? You were an only child?

BRIGGS: Yes, she was 38 when I was born, which was deemed very old. She came from a family of 11, so I imagine she’d always intended to have a big family. But she nearly died giving birth to me, so she was told she couldn’t have any more children. Mum idolized me and said yes to everything I wanted to do. My father withdrew. He would read the paper at the table and I realize now that he had opted out, in a childish sort of way. I think he felt rather hurt. As I grew older, I found it all terribly embarrassing. As time went on, he and I would almost kiss when we met up. Well, I’d give him a peck on the cheek and he did, too.

GRAVETT: As an only child, did you ever feel deprived or isolated?

BRIGGS: Well, I’d never known anything else, so what could I compare it with? I wasn’t aware of having been an only child. When you’re young, you don’t think of that as being abnormal. I suppose it makes you closer to your parents because they’re your entire family. I was closer to my mother. It could get rather unpleasant because she formed an alliance with me, like most mothers of her type, I suppose, who get more interested in their child than in their husband. It seems to happen quite naturally, but once the husband has served his function, it all gets concentrated on the child and the husband falls into the background. I think that kind of simple, unsophisticated woman does tend to put all in love on her children. My mum and people of her generation with their lack of education can’t be blamed, really. She threw all her love on me and slightly cold-shouldered my father. I was the apple of her eye because I was all the things that Dad wasn’t. I was educated — potentially middle-class, respectable, wearing a suit and tie, as she hoped, a bank-manager type, but that didn’t quite happen! I would never see her without that bloody comb coming out. That’s an example of it; wanting you to have neat and tidy hair.

Sex was never discussed. They were both very hung up about sex. I remember this book being handed around at school showing a baby growing inside a woman. I was flabbergasted. I didn’t reach puberty until after I left school. So when I was 14, having been quite good at games, I was suddenly surrounded by these enormous men with hairy chests and enormous dicks and I was still a little boy. I didn’t have a girlfriend until I was 17 — and even then, as I was still living at home, we didn’t get up to much. The idea of getting a girl pregnant and being thrown out of college was just too terrifying. I drank my first beer when I was 21.

GRAVETT: Why did you want to do a biography about your parents?

BRIGGS: I wanted to do something about the past and that house, because it was such a big part of my life. Apart from my National Service, I spent my first 25 years living there.

GRAVETT: Did you work mostly from memory or did you go back to your home?

BRIGGS: I went back to Ashen Grove a few times, but I can remember so much — even the wallpaper pattern in the airing cupboard.

GRAVETT: What was it like to be working from memory, rather than principally from your imagination, as in your other books?

BRIGGS: I wanted to particularize it. So I had to focus so closely on every detail that sometimes I’d draw things I’d forgotten I knew. Like the basket where the dirty washing went, under the sink, that I’d completely forgotten. What the tea tin looked like: red with slanted gold lettering. The catch on the cupboard door of the dresser, the way my dad always pulled out the drawer, when he sat in his regular seat in the kitchen, for an arm rest. I put that in.

GRAVETT: Before your parents died, had you already started to be successful?

BRIGGS: Well, they died in 1971, so I was earning a living by then. Oh, and I’d won the Kate Greenaway Medal. My mother would bore the neighbors to death about that.

GRAVETT: What do you think your parents would have thought of your success and life now?

BRIGGS: I think my mum would have been disappointed that I’ve never had children. She’d certainly be bemused by that fact that I’ve had a partner for the last 20 years. She would have loved that fact that I’ve been on television and in the papers.

GRAVETT: Are you like your parents?

BRIGGS: In some ways, not at all. They just didn’t understand the things that make me who I am, like art or jazz. But I do have a working-class obedience and fear of minor authority — like parking in the wrong place or not paying my rates in time — which I get from them.

GRAVETT: Who do you take after more, your mother or your father?

BRIGGS: I’m told Dad used to run down the stairs at breakneck speed. I do the same. I may have some of my mum’s snootiness. When I went to art school I got terribly snobbish. I hated the fact that Mum hung up the washing in the kitchen. Every time you’d stand up, a bloody sheet would slap you in the eyes. And physically, my mouth cracks at the corners exactly as my mum’s did.

My dad used to have certain rituals. He always washed in the kitchen sink. When it was suggested that he might use the bathroom, he’d say “I couldn’t do that, son, I’m filthy!” The bathroom seemed to be treated like a throne room and only used on special occasions. He had this thing about the bath. He always looked upon it as a slightly dangerous activity. He only ever had one once a week. He had to wrap himself in nightclothes and go to bed immediately, in case he’d catch a cold. He was amazed when I might have a bath in the middle of the day and then sit in the garden. He thought that was almost certain death. He was a bit of a do-it-yourself fanatic. He used to box in the beautiful Edwardian balusters with hardboard. Everything paneled he wanted to cover in hardboard and make more modern.

GRAVETT: During the War, you were evacuated out of London. Was that a difficult time, being away from home?

BRIGGS: I had a few dreams about running away and going back home, but it was cozy. I was looked after by my auntie and her friend. It was better than going to strangers. They took me in to avoid having some stranger billeted on them. They used to send evacuation officers ‘round saying “You’ve got this room so you can take two.” I used to draw on letters I’d send home.

GRAVETT: In one scene in the book you’re out in the park with your father and you’re almost hit by a German V-1 bomb. That must have been frightening?

BRIGGS: No, it didn’t bother me that much, but I remember being shocked that the doodlebug was blue underneath, because I’d only seen pictures of them in black-and-white films. It was alarming though to hear this awful bang over Putney, knowing that people were being killed.

GRAVETT: After the War, were you well-behaved at grammar school?

BRIGGS: Oh yes, Mum was thrilled. The school made us carry an elocution book in our blazer pockets. There was this one incident, though, when I was driven home in a Black Maria police car. My friends and I had got inside a bombed-out old golfing club and taken some billiard cues inlaid with ivory. Unfortunately, when we were playing at fencing with these cues, a chap came out of his back garden and asked, “Where did you boys get those?” It turns out he was an off-duty copper. Imagine if the police had run us in. Our names would have been in the local paper and my mum would have died. That kind of thing could have seriously buggered up your whole life.

UG

GRAVETT: There seem to be aspects of your childhood in your latest strip cartoon book, Ug, Boy Genius of the Stone Age and His Search for Soft Trousers. Ug has all sort of bright ideas to improve things — that there must be something better than stone trousers, stone bedsheets and pillows — but his parents are stuck in their ways.

BRIGGS: As you get older, you don’t like change, because it’s a mark of time marching on. In Ug, as well as in The Man, there’s a young boy who is more intelligent than his parents, as I was a bit more intelligent than my mum and dad. They weren’t stupid, but they hadn’t had the education I had. In The Man, you have this middle-class, educated, artistically minded boy talking to a kind of working-class, no-nonsense Man. And it’s the same in Ug; the boy is exasperated by their rejection of his ideas, and they’re exasperated by him. Because they’re living in different worlds.

GRAVETT: Ug comes up with these inventions, but doesn’t always realize their full potential.

BRIGGS: That’s right. He’s got the idea for a house, of wanting a space outdoors that’s enclosed instead of their cave. He builds a wall to about knee height, so he’s on the way to building a house, but can’t get any further. Can’t quite finish it off. Same thing when he nearly invents the wheel. He just likes to roll it downhill and jump in the air saying “Whee!” almost saying the word “wheel” without knowing it. It’s always intrigued me how long it takes people to think of things. Look at chimneys. All they used to have was a fire in the middle of the floor and a hole in the roof. It took centuries for somebody to think, “Why don’t we build something to take the smoke away?” Then, when they’d invented the chimney, they kept building them wider and wider because they found they smoked. It wasn’t until the 19th century that Rumford invented a tiny flue, about six inches across, to suck away the smoke. All that time to make these minute advances! It’s amazing there’s any progress at all.

GRAVETT: From the second page, the book is sprinkled with the occasional funny footnote explaining the anachronisms. Why did you bring them in?

BRIGGS: As I was writing the dialogue, I found myself thinking, “Oh God, they wouldn’t have iron or butter or summer holidays back then.” But I left them in as if they’re a mistake and then made up all this factual nonsense to explain everything.

GRAVETT: Have you ever been interested in drawing a newspaper strip?

BRIGGS: I did enter a strip competition back in 1983 run by the Sunday Times. I came in second. My main incentive was that they said the winner would get a weekly space in the paper, but they didn’t even give the winner [Punch cartoonist David Haldane] any space. Eight of those strips were later published in the Guardian. They had asked me to do a daily Fungus strip for six months, but it’s a huge task. I’d want to do enough to get a book out of it at the end, otherwise it just disappears into the pulp. I enjoy reading Steve Bell’s If... strip in the Guardian. I wish they’d give him more space. It’s so narrow and the panels are so vertical. If I did a strip, I’d want more space to cut it in half across and have a double tier of three panels to avoid those awful vertical panels.

GRAVETT: Do you enjoy Posy Simmonds’ work?

BRIGGS, Oh yes, a lot. Wonderful. Not so keen on Claire Bretécher. I like her ideas but get bored with those heavy repetitive drawings of great puddingy women. It’s lacking in variety.

GRAVETT: How about British comics like 2000 AD?

BRIGGS: I’ve seen them but I don’t take much interest in them, because they’re violence and war for the most part. That’s what’s wrong with comics. Most of the subject matter is so vile! I don’t see why they shouldn’t be perfectly straightforward. Why has it always got to be sex and violence? I thought we’d outgrown all that in the ‘60s. In Britain, comics aren’t considered anything, but when you see the subject matter of some of them, you can understand why! It’s always the same old naked girl strangling snakes or with bats in her hair. My “unmentionables” are terribly cozy compared to them.

I once joined the Society of Strip Illustration [by 2002 known as the Comics Creators Guild, now defunct] and went to few meetings and felt like a fish out of water. I felt they regarded me as some Beatrix Potter figure, all sweet and pretty! Then I was going to join the Cartoonists’ Club of Great Britain, but they were all hard newspaper cartoonists and I didn’t fit in there either. I did join the Society of Authors, but feel out of place there too, as they’re all proper writers.

GRAVETT: What would you have done if you hadn’t pursued illustration?

BRIGGS: I probably would have had a bash at being some sort of writer or journalist. I’d have tried radio plays, stage plays, short stories, novels, all of those.

GRAVETT: Who do you enjoy reading?

BRIGGS: Philip Larkin’s been one of my favorites. Stevie Smith’s poetry, William Trevor, all sorts. I get piles of second-hand books.

GRAVETT: I know you also enjoy jazz.

BRIGGS: I grew up with trad jazz, then got bored with that and moved on to what was modern jazz in the ‘50s. Most of them are old or dead now!

GRAVETT: Any hobbies?

BRIGGS: I enjoy walking in the country, fishing, rummaging round second-hand bookshops, collecting and framing jigsaw puzzles of the Queen Mother, collecting LP covers of Mrs. Mills and amusing headline adverts for the local paper. I got one the other week that reads “Five Pairs of Shoes To Be Won!”

GRAVETT: When you were an Art teacher, did you encourage students to take up comics?

BRIGGS: No, but there were usually one or two each year who wanted to do it anyway. In fact, there was quite a strong feeling against it then, people who disapproved of cartooning in the old way art schools always did, as something lower-class. Incredible! That’s the whole daft thing about fine art. The most you can ever hope to get is an exhibition in the West End, where you’re seen by maybe a few hundred people. Far more people get to see you if you’re published in a book or magazine.

GRAVETT: You’ve never had children of your own to try your books out on.

BRIGGS: No. I know traditionally people do books like these for a particular child, for example as Beatrix Potter or Lewis Carroll did. Perhaps it would have been easier for me. Then again, perhaps I would have been tired of children and wouldn’t have wanted to write children’s books.

GRAVETT: So many of your books end with loss, a departure, like the end of childhood — The Snowman melting, The Bear swimming home, The Man absconding.

BRIGGS: All the endings are a bit sad. I don’t know how you can avoid that. The stories obviously couldn’t go on. The Bear couldn’t go on staying in the house. The Snowman must melt sometime. It all seems perfectly natural.

GRAVETT: Given your success, do you feel more optimistic about life now?

BRIGGS: God, I’ve never felt optimistic about anything. It’s all just confirmed my worst fears! I think I’ve always been the same: fairly pessimistic, miserable, grumpy and bad-tempered. I was unlucky in that aspect of life, but plenty of people are unlucky. You could be in a wheelchair all your life, for God’s sake. People have terrible lives. I’ve been very lucky. I haven’t had any major illnesses. Although they are on the way, of course.

GRAVETT: With every book that you produce, you’ve always said it’s going to be your last, don’t you? But you always find another to do?

BRIGGS: Yes, that’s my parents’ work ethic. Even now, I still feel guilty if I’m not working.