“Urasawa Naoki wa wakai koro kara no ‘otona’”

from Manga no fuka-yomi, otona-yomi (Over-Readings and Adult Readings of Manga; East Press, 2004)

Translated by Jon Holt and Teppei Fukuda

* * *

Wow, this is going to be my commentary (kaisetsu) essay for Urasawa Naoki.

MONSTER and 20th Century Boys (Nijū seiki shōnen)—that Urasawa Naoki.

Urasawa—I can’t help myself being emotional about it.

Are you asking what makes me emotional? It’s that, if this were the 1980s, Urasawa Naoki would be the author you recognize for YAWARA!

But I’ll tell you a secret. Before that, Urasawa was one of the children of Ōtomo Katsuhiro from the days of his 1970s short story phase.

In those early days, he had Ōtomo’s sense of dry cruelty—that combined sense of cool (koiki) with some French avant-garde thrown in; that enlightened feeling of detachment.

More than his heroes and heroines, his stories and his line work gave fresh life to the countless faces of people that can you easily encounter in your daily life, each person with a different face, a different character.

That’s right. If I can get my readers to look at his early short story collections, such as Dancing Policeman (Odoru keikan), N・A・S・A, or JIGORO! (Shogakukan published these all in paperback in 2003), then I bet people would understand how much he Ōtomo-ed in his early manga.

These were all part of a group of works created by an artist born in the 1960s, who was in his mid-20s, working through the years around 1984 and 1985. His work resembled Ōtomo’s so much it was like a spitting image—in terms of its sensibility, its goals, and, of course, the pictures.

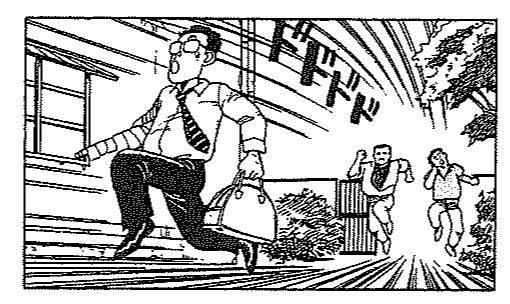

For example, in "N・A・S・A" (original publication date unknown), there’s that scene with a Ozu Yasujirō feel of two men—one quite elderly, one middle-aged—sitting on a bench (Figure 1). Or how about the way that guy runs from "Crash Dance" (Kurashu dansu, [original publication date unknown])? (See Figure 2.) If people out there know Ōtomo Katsuhiro, I bet they will say, “Oh yeah!”

Even though these all are short works, with the fate of being seen as his études as a manga artist, of course since this is Urasawa Naoki, they are a lot of fun as works of entertainment. Moreover, let me say—and this is very important—it is true that while Urasawa was at this time drawing these pieces, he was learning from Ōtomo how to do Ōtomo, but at the same time he was exploring a way to Urasawa-ize what he was doing too. I have no doubt about that.

After all, look at the Urasawa Naoki who gave us YAWARA!—and then, during an interview around when he drew MONSTER, he could make this kind of passing remark:

“It was YAWARA—I drew it just to test my skill.”

Dang, how cool is that? C’mon, Urasawa!

When I heard him say that one sentence, I realize this was not just any run-of-the-mill manga artist. After all, he was saying that what he turned into a megahit was just an experiment for him to see if he could draw an entertainment manga that would sell big numbers.

Not just anybody could say such a thing. To say such thing, you have to be able to calmly and objectively think what you want to express, and to think how you can express it, and to think how you can make it a successful piece of entertainment.

Urasawa Naoki had long known what kind of person he was. That’s why he had known time was the thing necessary for him to turn that dark “something” within him into pure entertainment.

And this “time” has two aspects. One is time to practice, in order to become able to make his “something” into a pop product. The other is the time needed to gain an environment and status to be able to draw such great work. Urasawa succeeded because he had “cleared” those two time hurdles.

If Urasawa had tried to be successful with that “something” of his from the very beginning, he probably would have ended up just becoming some alternative manga artist. However, I think Urasawa had in him a very strong desire to make pure pop (to universalize). That’s why he also was a strategist, a person who understood he had to clear those two time challenges.

Even though I see most of his early work as Urasawa aping Ōtomo, those same works also quite clearly reveal his propensity to entertain. You notice it in how he can cut a scene on a sentiment, or right before he might make you cry - but more than anything, his entertainment quality comes from the cuteness of the young women he draws.

In his Dancing Policeman series (which ran in Big Comic and its supplement issues from 1984 through 1986), the protagonist does not have a face that has a strong character (kyara) appeal, but the police lady Ms. Mizuhara is so darling (Figure 3). That is an example of one of the weapons you find in Urasawa Naoki that you don’t find in Ōtomo Katsuhiro.

Actually, that might explain Yawara-chan’s appeal—maybe Urasawa knew he could do this and strategically manipulated us with her. Of course, when I talk about “cuteness” (kawaisa), it’s not only just his ability to create cute faces for his female characters, but also it includes the whole image he pulls off with his female characters and their personae.

While Ōtomo Katsuhiro was serializing his AKIRA (1982-1990), Urasawa Naoki was in his mid-20s and drawing Dancing Policeman; and, by his late 20s, his Pineapple Army (Painappuru ARMY, [1985-1988, written by Kudō Kazuya]). The latter is a story about a volunteer army that is a kind of prototype for his later Master Keaton (MASTER Kiiton), but during this time he was still caught up in the world of Ōtomo, especially in the way you see him handle the children in that manga.

So, by the time he is in his 30s, he is drawing both YAWARA! (1986-1993) and Master Keaton (1988-1994), and this is when he first breaks away from the gravity of Ōtomo.

Truth be told, for a manga reader like me, who had lost his innocence long ago, although I could appreciate the entertainment qualities of his manga, I think I was probably not the right Urasawa reader of his YAWARA! and Happy! (Wow, he does use a lot of English in his titles.)1 On the contrary, I had long felt the “interesting quality” (omoshirosa) that Urasawa had were his works up to about Pineapple Army. That’s because I had been able to feel in them that special Urasawa “something” lurking just barely out of sight.

That’s also why when MONSTER began in 1995, I found myself going, “Well, ok, now I get it.”

It all had taken him about 10 years. He had waited to gain the right environment and enough skills to turn his “something” into a true product. (By the way, I am not saying that all of Urasawa’s work up to that point were just practice.)

In fact, these points are pivotal when it comes to Japanese comics: patience to endure long detours, an awakened sense of pure distance from the subject, and the power to make rock-solid story constructions.

If you want to say that Urasawa Naoki is a successor to Ōtomo Katsuhiro, who is one of the most important figures of the 1970s postwar manga, you also have to clearly draw a line and separate those cool comics by Ōtomo followers from the likes of what was done by Kajiwara Ikki [writer of Kyojin no hoshi (Star of the Giants)], in hardcore sports manga, or in the hot-blooded style of manga, etc. It is this latter, other line of influence that really has become what is one the main trunks of what we have mostly today in manga. And yet, this is not what we would call “mature” (or: adult [otona]), if you are looking at what people in their late adolescence (shishunki) or young adulthood (seinen zenki) should be like.

The quality of “adult-like” (otona-ppoi) that both Ōtomo and Urasawa had from their early days is really quite different from the blind, intuitive “hot-blooded” (nekketsu) quality that has been the main kind of style of most shōnen and seinen manga in Japan’s postwar period. I’m not saying theirs is a calculated kind of “adult” quality. Rather, what they have is something passionate but also contemplative—that is the “adult” feel you get from their works. (By the way, no calculating person ends up becoming a manga artist.)

Since the latter part of the 1980s, when more than half of the manga went the way of seinen (young male) comics, I believe at least a part of what today’s manga should be dealing with is exploring manga for “adults”.

If we think in that way, we can say that the existence of Urasawa Naoki might give us an answer to questions like these: “What exactly was the Ōtomo phenomenon?”; or “Can Japanese manga can grow into a ‘full adult’ after having been for so long ‘young adult’?” After a little chat with Mr. Urasawa, I can say quite confidently that the man is quite the theorist. He uses words that can teach us about manga. I think he is one of the few manga artists today who can respond to comics scholars overseas who require us to be responsible in giving them detailed explanations about our manga.

* * *

- [Editor's Note] Because this does not not entirely come across in translation, what Natsume is saying here is that Urasawa has a tendency to use English-language titles for his Japanese-language serials; for example, YAWARA!, Happy!, MONSTER, PLUTO and BILLY BAT all have titles that are rendered as so, in otherwise Japanese-language releases.