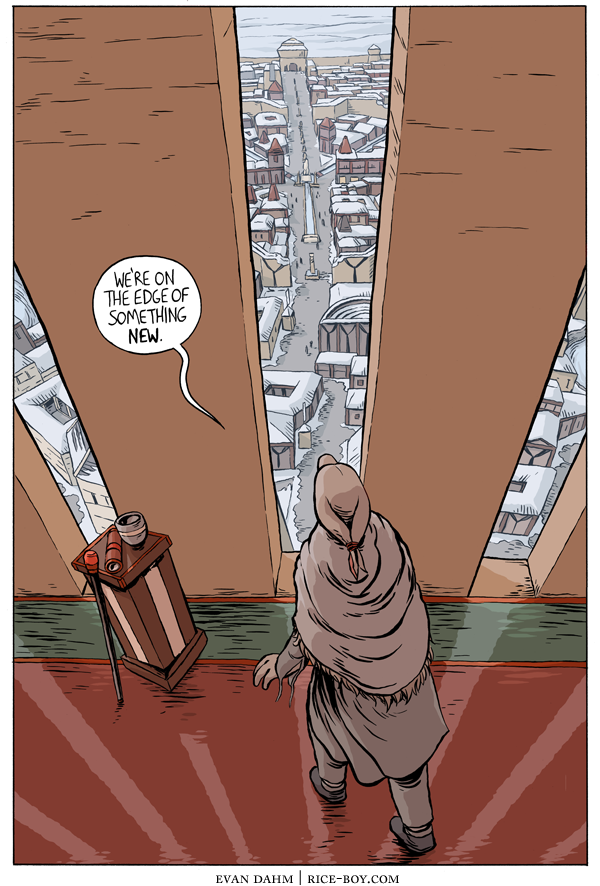

Watching an artist swerve from their well-worn trajectory always fills me with a small thrill of anticipation. If the creator in question is a novice whose work until now has been unique enough to deserve attention but otherwise lacked in sophistication, in insight, in technique or in depth then there is a kind of tentative excitement that this departure is exactly the act of liberation needed in order to advance their craft. When an established master announces their intent to test the boundaries of some genre or style unfamiliar to them the feeling is more akin to a giddy hope that they’ve found a way to to bring their honed sensibilities to bear on ideas and aesthetics that might have grown stale. At times, it’s possible that they might even invent something entirely new. While I would never be dismissive enough to describe cartoonist Evan Dahm as a neophyte -- even his first work Rice Boy evinced a command of voice and style and world so strong that it was easy to forgive any narrative sloppiness, wobbly line work and primitive coloring -- or undiscriminating enough to elevate him to the rank of genius just yet -- even as his pencils, inks and color design have improved by bounds, his world building can still feel arbitrary when striving to be intentioned, his characters inscrutable when even as in later works he has strived to render them more human, understandable. But there is no doubt he possesses a particular and valuable sensibility that marks every work he creates as uniquely, fascinatingly his. In the 14 years since he first began self-publishing, Dahm’s name has become synonymous with a kind of deceptively soft fantasy styling that combines a surrealism somewhere between Dr. Seuss and Salvador Dali -- all alien, rubbery flora dotting sprawling abstract geographies peopled by a spectrum of freakish fauna and connected only by dream logic -- with high-fantasy adventuring as indebted to Bone as it is to Tolkien and sprinkled over with just enough of the eerie and abject to prevent his colorful proceedings ever feeling too sanitary. If with Island Book, his first title released through a larger publisher, Dahm abandoned the deeply developed world of Overside to focus instead on a new world composed entirely of archipelagos, he still busied himself with a visual style, a worldbuilding approach, and thematic concerns (his subverting of the more odious elements of the “chosen one” paradigm, the privileging of knowledge and empathy over power and force) that recalled his work on Overside. And while his Vaatu rejects the swashbuckling globe trotting of earlier stories to offer instead what Dahm has dubbed an “anthropological fantasy epic” devoted to a critique of the mechanisms and ideology of empire, it is an epic all the same, intent on making its points felt through matters of overwhelming scope and scale and range and time. If Vaatu maybe more centralized and grounded in its telling than Rice Boy and Order of Tales, the world building is if anything even more expansive, more detailed than ever before.

Watching an artist swerve from their well-worn trajectory always fills me with a small thrill of anticipation. If the creator in question is a novice whose work until now has been unique enough to deserve attention but otherwise lacked in sophistication, in insight, in technique or in depth then there is a kind of tentative excitement that this departure is exactly the act of liberation needed in order to advance their craft. When an established master announces their intent to test the boundaries of some genre or style unfamiliar to them the feeling is more akin to a giddy hope that they’ve found a way to to bring their honed sensibilities to bear on ideas and aesthetics that might have grown stale. At times, it’s possible that they might even invent something entirely new. While I would never be dismissive enough to describe cartoonist Evan Dahm as a neophyte -- even his first work Rice Boy evinced a command of voice and style and world so strong that it was easy to forgive any narrative sloppiness, wobbly line work and primitive coloring -- or undiscriminating enough to elevate him to the rank of genius just yet -- even as his pencils, inks and color design have improved by bounds, his world building can still feel arbitrary when striving to be intentioned, his characters inscrutable when even as in later works he has strived to render them more human, understandable. But there is no doubt he possesses a particular and valuable sensibility that marks every work he creates as uniquely, fascinatingly his. In the 14 years since he first began self-publishing, Dahm’s name has become synonymous with a kind of deceptively soft fantasy styling that combines a surrealism somewhere between Dr. Seuss and Salvador Dali -- all alien, rubbery flora dotting sprawling abstract geographies peopled by a spectrum of freakish fauna and connected only by dream logic -- with high-fantasy adventuring as indebted to Bone as it is to Tolkien and sprinkled over with just enough of the eerie and abject to prevent his colorful proceedings ever feeling too sanitary. If with Island Book, his first title released through a larger publisher, Dahm abandoned the deeply developed world of Overside to focus instead on a new world composed entirely of archipelagos, he still busied himself with a visual style, a worldbuilding approach, and thematic concerns (his subverting of the more odious elements of the “chosen one” paradigm, the privileging of knowledge and empathy over power and force) that recalled his work on Overside. And while his Vaatu rejects the swashbuckling globe trotting of earlier stories to offer instead what Dahm has dubbed an “anthropological fantasy epic” devoted to a critique of the mechanisms and ideology of empire, it is an epic all the same, intent on making its points felt through matters of overwhelming scope and scale and range and time. If Vaatu maybe more centralized and grounded in its telling than Rice Boy and Order of Tales, the world building is if anything even more expansive, more detailed than ever before.

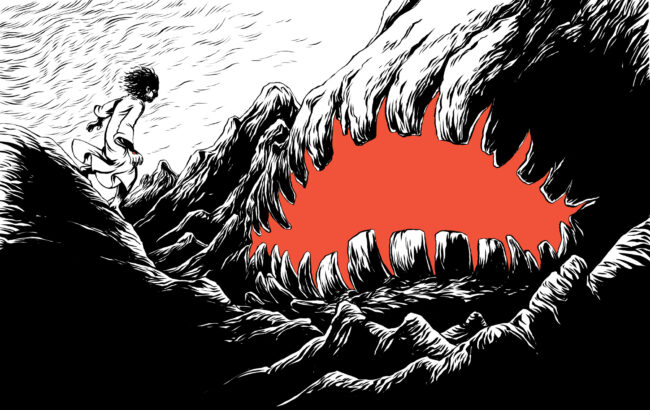

Dahm’s The Harrowing of Hell, by contrast, appears a major departure for the creator; less generous interpretations might even call it a shrinking. At a scant 120 pages (in contrast to the 439 pages of Rice Boy, the 744 pages of Order of Tales, the 1058 pages of the still-ongoing Vaatu), its sights are narrowed entirely to focus on the apocryphal accounts of Jesus Christ’s descent into Hell. While the tale of a Messiah marching into the inferno to free the souls of the damned from a lurid nightmarescape that painstakingly catalogues every possible transgression might suggest an excuse for the manner of grandiose depictions and surrealist imagery Dahm has long shown a talent for, his take on the Pit is reserved, quiet. Hell as he has it is not the inferno of Dante or the fields of apocalyptic fields of a Bosch but a prison planet whose architecture and masters suggest the Roman Empire that Constantine would establish in Jesus’ name (that the Hell in question is lorded over by a Satan wearing the raiment of Caesar and that the book opens on an epigram from The Life of the Blessed Emperor Constantine recounting Constantine’s fateful decision to align himself with Catholicism reinforce the impression). There is little gore here, little in the way of grand visual spectacle, only rows and rows of prison cells carved into the bedrock of the world and stretching on towards a central coliseum that seems eternally distant. The humans that huddle in this captivity are sexless, lifeless, the demons that oversee them not towering figures of infernal grandeur but scrabbling golems playing at the part of wardens; what reigns in Dahm’s vision of the Pit is not punishment so much as the threat of punishment, not the sadistic desire of fallen angels but the masochistic guilt and shame endemic to a system that has held for thousands of years that humans are fatally flawed sinners whose salvation can only come from an authoritative, martial hand: even Adam and Eve reject Jesus’ offer of salvation because they trust “Only the Lord. And His Law.”. As if to match these thematic concerns, the expressive colors that lent so much life to the world of Overside as explored in Vaatu and Rice Boy have been bled out; fled as well are the bold, story-board-style layouts that lent Order of Tales its adventurous spirit. In the interest of hammering home the isolation and deprivation of his particular vision of the punishment Dahm has adopted a wide, almost cinematic approach to page and paneling that emphasizes space, distance, and silence, and then uses clashes between his heavy inks and either the white of the page or a burnt orange shading to convey a world austere, severe, heavy with consequence and devoid of comfort.

The closest aesthetic element linking Harrowing to Dahm’s earlier work is his depiction of Jesus as a doe-eyed and bobble-headed diminutive cast from the same mold of prior protagonists like Rice Boy and Koark and Vaatu, yet where those earlier heroes all played central roles in the toppling or reformation of broken systems and tyrannical rules, the Christ of Harrowing inadvertently bolsters them. His mission ends in failure. The revolution his actions foment is not an overthrow of the oppressive empire and restrictive morality he advocated against but is instead a bolstering of both. Indeed the book’s grand thematic thrust is that while Christ’s politics (and Dahm is quick to make clear he intends the story to be read politically; in an essay included at book’s back he says he drew much of his inspiration from the Gospel of Mark given “it was practically a work of political theory using the framework of a biography...its intense thematic focus and its anti-authoritarian arguments at odds with practically everything we’ve ever heard about Jesus—even much included in the later gospels...”) began as a radical touting of redistribution, revolution, and absolution they were and still remain co-opted by the same worldly authorities he denounced in his lifetime the better to promote everything from the empire building of Constantine to the trumpets of war now sounded by contemporary Evangelicals who waste no time reminding their opponents that Jesus proclaimed he “came not bring peace, but a sword.” Perhaps this is a failure on his part as much as it is the work of any antagonistic party, for time and again when he is asked to define himself he responds with some variation of “Who do you say that I am?” Even before Pilate, when asked if he is the self-styled King of the Jews and with his life in the balance, he can only respond, ”...is that the story you hear of me?” From a Jesus who had earlier remarked “[Stories are] the seed of the kingdom...what is there but stories...” this repeated refusal to define himself and the meaning of his own style of teaching might have read to the astute among his followers as an invitation to reinvention, an invitation to liberty from old beliefs that the Messiah would usher in a heavenly kingdom founded on “swords, warfare, and law,” but it was also as much an invitation for his enemies to reimagine him and his words as they saw fit. That Jesus’ followers would greet the resurrected Christ with a confounded “Who are you?” as they behold the stigmata on his hands, then, follows as tragic and inevitable.

The closest aesthetic element linking Harrowing to Dahm’s earlier work is his depiction of Jesus as a doe-eyed and bobble-headed diminutive cast from the same mold of prior protagonists like Rice Boy and Koark and Vaatu, yet where those earlier heroes all played central roles in the toppling or reformation of broken systems and tyrannical rules, the Christ of Harrowing inadvertently bolsters them. His mission ends in failure. The revolution his actions foment is not an overthrow of the oppressive empire and restrictive morality he advocated against but is instead a bolstering of both. Indeed the book’s grand thematic thrust is that while Christ’s politics (and Dahm is quick to make clear he intends the story to be read politically; in an essay included at book’s back he says he drew much of his inspiration from the Gospel of Mark given “it was practically a work of political theory using the framework of a biography...its intense thematic focus and its anti-authoritarian arguments at odds with practically everything we’ve ever heard about Jesus—even much included in the later gospels...”) began as a radical touting of redistribution, revolution, and absolution they were and still remain co-opted by the same worldly authorities he denounced in his lifetime the better to promote everything from the empire building of Constantine to the trumpets of war now sounded by contemporary Evangelicals who waste no time reminding their opponents that Jesus proclaimed he “came not bring peace, but a sword.” Perhaps this is a failure on his part as much as it is the work of any antagonistic party, for time and again when he is asked to define himself he responds with some variation of “Who do you say that I am?” Even before Pilate, when asked if he is the self-styled King of the Jews and with his life in the balance, he can only respond, ”...is that the story you hear of me?” From a Jesus who had earlier remarked “[Stories are] the seed of the kingdom...what is there but stories...” this repeated refusal to define himself and the meaning of his own style of teaching might have read to the astute among his followers as an invitation to reinvention, an invitation to liberty from old beliefs that the Messiah would usher in a heavenly kingdom founded on “swords, warfare, and law,” but it was also as much an invitation for his enemies to reimagine him and his words as they saw fit. That Jesus’ followers would greet the resurrected Christ with a confounded “Who are you?” as they behold the stigmata on his hands, then, follows as tragic and inevitable.

And yet if Dahm is ambivalent of the Christ’s faith in the liberating power of stories and his unwillingness to define them, an overview of his own work -- fiction and otherwise -- would reveal it is a faith he is deeply sympathetic to. In an essay published on Medium, he himself suggested that one of the major reasons he had worked with surrealist imagery for so long was that “(its) value to me is exactly in (its) meaning-agnosticism, (its) chaos and heterogeneity...part of my interest in this is as a way of deconstructing how I interact with the world, and the various myths of objectivity we seem to be preoccupied with.” In another, later interview with The Comics Journal he echoed the thought, asserting a resistance to worldbuilding and storytelling styles that insist on an "‘objective’" history that is limiting and imperialistic and doesn't do justice to people's lived experiences.” Despite all the deviations of style and narrative that suggests The Harrowing of Hell represents a grand departure from Dahm’s earlier output, the story’s preoccupation with narrative as perhaps the single most powerful and potentially pernicious force that shapes the world and the suspicion of any who would attempt to define the world by imposing a single interpretation upon proves that Harrowing is, if anything, a development of it. For the mission of Dahm’s Christ is an attempt to overturn a history of oppression by telling a new type of story -- one of profound absolution -- in a way that emphasizes not the primacy of some defining myth but the agency and the well-being of those subject to its influence. It is not that Dahm or his Jesus distrusts fictions wholesale; it is only that both understand how easily the human desire for tidy and well-ordered narratives gives way too easily to those who would be happy to impose their own sense of order on the world at large, and that because of our predispositions there exists no better tool for such reshaping than storytelling. When Jesus offers to his Apostles that “stories are the way the Word can be given to (people),” he and his author both are not so much lamenting the limitations of language and humankind’s seeming reliance on fables to interpret the world as he is acknowledging this is the paradigm we have to work with; bucking against it would be as futile as trying to defy physics. In grasping after some way to explain the nature of the world, he seems to have conflated the opening lines of the Gospel of John with the famous proclamation of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus to arrive at the dictum “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word is all that is the case.”

And yet if Dahm is ambivalent of the Christ’s faith in the liberating power of stories and his unwillingness to define them, an overview of his own work -- fiction and otherwise -- would reveal it is a faith he is deeply sympathetic to. In an essay published on Medium, he himself suggested that one of the major reasons he had worked with surrealist imagery for so long was that “(its) value to me is exactly in (its) meaning-agnosticism, (its) chaos and heterogeneity...part of my interest in this is as a way of deconstructing how I interact with the world, and the various myths of objectivity we seem to be preoccupied with.” In another, later interview with The Comics Journal he echoed the thought, asserting a resistance to worldbuilding and storytelling styles that insist on an "‘objective’" history that is limiting and imperialistic and doesn't do justice to people's lived experiences.” Despite all the deviations of style and narrative that suggests The Harrowing of Hell represents a grand departure from Dahm’s earlier output, the story’s preoccupation with narrative as perhaps the single most powerful and potentially pernicious force that shapes the world and the suspicion of any who would attempt to define the world by imposing a single interpretation upon proves that Harrowing is, if anything, a development of it. For the mission of Dahm’s Christ is an attempt to overturn a history of oppression by telling a new type of story -- one of profound absolution -- in a way that emphasizes not the primacy of some defining myth but the agency and the well-being of those subject to its influence. It is not that Dahm or his Jesus distrusts fictions wholesale; it is only that both understand how easily the human desire for tidy and well-ordered narratives gives way too easily to those who would be happy to impose their own sense of order on the world at large, and that because of our predispositions there exists no better tool for such reshaping than storytelling. When Jesus offers to his Apostles that “stories are the way the Word can be given to (people),” he and his author both are not so much lamenting the limitations of language and humankind’s seeming reliance on fables to interpret the world as he is acknowledging this is the paradigm we have to work with; bucking against it would be as futile as trying to defy physics. In grasping after some way to explain the nature of the world, he seems to have conflated the opening lines of the Gospel of John with the famous proclamation of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus to arrive at the dictum “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word is all that is the case.”

It’s a theme apparent even in Dahm’s earliest and more exploratory Overside work; a pivotal element of Rice Boy’s arc involves its titular protagonist’s quest to acquire the Trill-Tongue, a fabled meta language that bends reality to match the speech of the user. As metaphors go it may be the most bald in all of Dahm’s oeuvre, here used to less to hammer home larger concerns about the relationship between words and world and more as an exploration of the expressive potential of comic that serves another purpose as plot device. Less formally experimental but more thematically revealing is that even in the earliest stages of Rice Boy Dahm flirted with establishing a connection between the dissemination of story and the building of domineering empires: it is not even fifteen pages into the first of his Overside stories before he introduces the history of the racist and tyrannical King Spatch I, the newly appointed ruler of the small kingdom of Sunk who used his newfound status as “Fulfiller” (a kind of Chosen One appointed by a roving trio of prophets who’ve been tasked with restoring an entity known as the Avatar of Mind but as often referred to simply as “God”) to legitimize an ethnic cleansing of his kingdom and an expansionist military campaign; that he would in time write a book meant to legitimize his own legacy and his son Spatch II’s claim to the prophecy only serves to literalize what might have been relegated to a subtext. In case there was any mistaking Dahm’s intent to denounce this kind of pernicious myth-making, though, he has Rice Boy himself declares that Spatch I’s interpretation of the Prophecy of the Fulfiller -- like the Prophecy of the Fulfiller itself -- ”...are just written words! They know nothing more than we do!”And yet while this statement is meant to read as one of triumphant defiance, reclaiming the fate of Overside’s people for themselves, it is in truth ultimately incorrect. Both Spatches’s interpretation of the prophecy proved faulty, yes, as did every other characters, yet the prophecy itself is fulfilled according to the dictates laid out, regardless of the misunderstandings spinning around it: it is no judgment of the prophecy that it was interpreted incorrectly so much as it is a judgment on the races of Overside who, through their own lack of vision and understanding, evinced like the people of Harrowing how easily they might read into such stories their own desires and in doing so be blinded to the truth. Unlike in Harrowing, however, the misinterpretation does nothing to stem the tide of history correcting itself; if anything the Prophecy of the Fulfiller and both Spatches’s mangled interpretation of it are necessary for its fulfillment, suggesting some faith that no matter what the desires of individuals and empires the truth will out; the narrative will be maintained.

It’s a theme apparent even in Dahm’s earliest and more exploratory Overside work; a pivotal element of Rice Boy’s arc involves its titular protagonist’s quest to acquire the Trill-Tongue, a fabled meta language that bends reality to match the speech of the user. As metaphors go it may be the most bald in all of Dahm’s oeuvre, here used to less to hammer home larger concerns about the relationship between words and world and more as an exploration of the expressive potential of comic that serves another purpose as plot device. Less formally experimental but more thematically revealing is that even in the earliest stages of Rice Boy Dahm flirted with establishing a connection between the dissemination of story and the building of domineering empires: it is not even fifteen pages into the first of his Overside stories before he introduces the history of the racist and tyrannical King Spatch I, the newly appointed ruler of the small kingdom of Sunk who used his newfound status as “Fulfiller” (a kind of Chosen One appointed by a roving trio of prophets who’ve been tasked with restoring an entity known as the Avatar of Mind but as often referred to simply as “God”) to legitimize an ethnic cleansing of his kingdom and an expansionist military campaign; that he would in time write a book meant to legitimize his own legacy and his son Spatch II’s claim to the prophecy only serves to literalize what might have been relegated to a subtext. In case there was any mistaking Dahm’s intent to denounce this kind of pernicious myth-making, though, he has Rice Boy himself declares that Spatch I’s interpretation of the Prophecy of the Fulfiller -- like the Prophecy of the Fulfiller itself -- ”...are just written words! They know nothing more than we do!”And yet while this statement is meant to read as one of triumphant defiance, reclaiming the fate of Overside’s people for themselves, it is in truth ultimately incorrect. Both Spatches’s interpretation of the prophecy proved faulty, yes, as did every other characters, yet the prophecy itself is fulfilled according to the dictates laid out, regardless of the misunderstandings spinning around it: it is no judgment of the prophecy that it was interpreted incorrectly so much as it is a judgment on the races of Overside who, through their own lack of vision and understanding, evinced like the people of Harrowing how easily they might read into such stories their own desires and in doing so be blinded to the truth. Unlike in Harrowing, however, the misinterpretation does nothing to stem the tide of history correcting itself; if anything the Prophecy of the Fulfiller and both Spatches’s mangled interpretation of it are necessary for its fulfillment, suggesting some faith that no matter what the desires of individuals and empires the truth will out; the narrative will be maintained.

As such statements go, it may be Dahm’s most generous, his most earnest; if there is some ambivalence in Rice Boy regarding the transformative power of storytelling it eventually gives way to a trust that it is all to the good. It is also the most coy he is willing to play: there is no mistaking the concerns of Order of Tales, which announces its preoccupation in its title. A chronicling of the life of Koark, last of a line of self-appointed Tellers whose mission it was to document and preserve the various tales of Overside, Order dedicates every element of its plot and characters to making explicit a metatextual awareness of how fictions can reorder the world. Seven times throughout the story Koarak (and by extension, Dahm) freezes the action to recount Overside’s most important or relevant histories and folk-tales in convincingly designed mock-ups of illuminated manuscripts that hammer home the cultural relevance of each of these world-defining recountings; characters frequently admonish one another for failing to understand they are “not the hero of this story” or for failing to grasp their “role in history.” Even Koark’s ultimate goal is the acquisition of one more story, the fabled “The Ascent of the Bone Ziggurat” that, his father told him, hides in its details a secret so dangerous it might be used to disrupt the current order of the world. What Koark does not discovers until nearly the end of Order is that the story of the Bone Ziggurat was so jealously guarded because Gerrah, a renegade Teller who sought to use the knowledge contained in the Order’s collected tales for his own ends and who murdered Koark’s father, has used his knowledge of this same story to style himself as the prophesied resurrection of the long-dead king Rog. More explicitly, he realized that in a world where people relied on stories to communicate their history and, with it, their values, their ideologies, their cultures, that anyone who understood the nature of those tales better than all others possessed a skeleton key for influencing other’s worldview and, by extension, the world itself. Hence why he chose to take on the title of a legendary tyrant to cow the superstitious into servitude, why one of his first acts of violence in the story is to oversee the burning of a library, why his army is expressly “composed of (people) who do not read or write...” and why he chose to murder the other Tellers for fear that they might use their knowledge of the stories against him. As a Teller himself he knows better than any the influence that stories, which so many others might dismiss as mere entertainment or cultural curiosity, have both in defining the interpretation of history and in the realization of its future.

As such statements go, it may be Dahm’s most generous, his most earnest; if there is some ambivalence in Rice Boy regarding the transformative power of storytelling it eventually gives way to a trust that it is all to the good. It is also the most coy he is willing to play: there is no mistaking the concerns of Order of Tales, which announces its preoccupation in its title. A chronicling of the life of Koark, last of a line of self-appointed Tellers whose mission it was to document and preserve the various tales of Overside, Order dedicates every element of its plot and characters to making explicit a metatextual awareness of how fictions can reorder the world. Seven times throughout the story Koarak (and by extension, Dahm) freezes the action to recount Overside’s most important or relevant histories and folk-tales in convincingly designed mock-ups of illuminated manuscripts that hammer home the cultural relevance of each of these world-defining recountings; characters frequently admonish one another for failing to understand they are “not the hero of this story” or for failing to grasp their “role in history.” Even Koark’s ultimate goal is the acquisition of one more story, the fabled “The Ascent of the Bone Ziggurat” that, his father told him, hides in its details a secret so dangerous it might be used to disrupt the current order of the world. What Koark does not discovers until nearly the end of Order is that the story of the Bone Ziggurat was so jealously guarded because Gerrah, a renegade Teller who sought to use the knowledge contained in the Order’s collected tales for his own ends and who murdered Koark’s father, has used his knowledge of this same story to style himself as the prophesied resurrection of the long-dead king Rog. More explicitly, he realized that in a world where people relied on stories to communicate their history and, with it, their values, their ideologies, their cultures, that anyone who understood the nature of those tales better than all others possessed a skeleton key for influencing other’s worldview and, by extension, the world itself. Hence why he chose to take on the title of a legendary tyrant to cow the superstitious into servitude, why one of his first acts of violence in the story is to oversee the burning of a library, why his army is expressly “composed of (people) who do not read or write...” and why he chose to murder the other Tellers for fear that they might use their knowledge of the stories against him. As a Teller himself he knows better than any the influence that stories, which so many others might dismiss as mere entertainment or cultural curiosity, have both in defining the interpretation of history and in the realization of its future.

It’s fitting if predictable, then, that his ultimate undoing results when Koark at last stumbles upon the truth of the Bone Ziggurat and uses the knowledge he gleans from the story to convince Gerrah’s own superstitious forces that he, Koarak, is in fact the resurrection of an older king, Obilik, whose sword and title Rog claimed for his own in an act of symbolic usurpation.. While Koark himself does not defeat Gerrah -- that privilege is reserved for his accomplice the Bottle Woman, whose predecessor’s own part in the “Ascension of the Bone Ziggurat” reveals the only method for undoing Gerrah’s magical weapon and unveiling him for the fraud he is -- it is not important that he do so in martial combat. His mission is not murder, a method for resolution that Dahm has shown himself highly skeptical of. His task is before anything else the preservation and dissemination of information to the betterment of Overside’s denizens; his victories will be not matters of force but of enlightenment, a fact only reaffirmed in the final scene. “There are more stories...and we saw the danger in keeping them secret,” Koark’s traveling companion The One Electric cautions him in an attempt to sway him towards continuing the mission of his Order, but the caution seems one as directed at the reader as it is at the Teller. In fact it might easily be read as a precursor of Dahm’s suggestion in Harrowing that to leave stories unguarded and undefined, vacant of your imposed meaning, is no way to guarantee their objectivity but in fact an abdication of one’s duty to define stories the better to insure they are not co-opted to malevolent ends. For in the absence of the teller’s guiding hand others will, inevitably, find some way to bend it to twist it to more nefarious purpose.

Or perhaps it is not even that, and that stories do have a will of their own, a kind of desire or ideology greater than even their creator’s intent that was imbued in stories at their creation that works to hollow out the host and reprogram them the better to achieve expression? Certainly that is what Gerrak suggests when at last he and Koark meet at the climax of Order. “You know how the tales gnaw at our minds. I had no choice but to take up Obilik’s sword and conquer. How can we invest so much in these stories never knowing if they are true? We must make them truths,” he proclaims with an energy that suggests surrender as much if not more than it does agency: here, at the apex of his power, his doubt betrays a deep distrust if not resentment of the very thing that has enabled his rise. It is not a doubt that Arrius, current emperor of the Sahtan empire that sits at the heart of all action in Vaatu, might disabuse him of. Heir to a position he never desired or rightly understood, Arrius has been defined from birth by his role in an Empire he is ostensibly the ruler of but which he has never felt even an inkling of control over. While by tradition he is said to be the “sole mortal representative” of the Sahtan god Tarrus, in actuality he exercises less power than even his functionaries. His role is purely ornamental: his proxies scheme to marginalize his influence when they are not actively plotting his demise, his general proceed on campaigns of expansion he is not aware of, even his daughter pursues romance outside of his royal dictates. To the subjects beyond its wall the grand tower he lives in might symbolize some phallic statement of power and authority but to the man trapped at its crown, watching from its barred windows as his empire spins further outside of his control and he waits for one of any number of factions to assassinate him, it must feel like he has been consigned to the role of prisoner. Even his name seems to chafe: “Sahtan names have such a heaviness. So much history. Blood. Arrius Morrant,” he spits when introducing himself to Vaatu, his disgust for his place in the grand genocidal story that is empire palpable. Try as he might in his small ways to reframe the narrative -- hiring the poet Carnin to spin tales to his court that might recast the Sahta’s role in the world in new light, taking on the painter Velas Dagren to provide renderings of Arrius that will “show his connection to the city, and the empire, his place in history” in some better light, staffing his court with prisoners from conquered lands upon whom he bestows titles and friendship in hopes of expanding their race’s representation in the empire’s governance -- he knows his gestures are futile. He is, as his wife Enteyer describes all the people of the Sahtan, “a story -- given fleeting name and form,” one told by empire and so bound by the conventions of its narrative, able to act only in the narrow confines proscribed him.

And yet if Arrius’ bondage is unfortunate it is hardly the exception; in some ways he might even be considered remarkably blessed given that he was allowed a story of his own at all. For his is an empire where custom has it that even citizens must burn their names before marriage only to then be handed one by the state: if Enteyer’s words have any truth and individuals are each a story onto themselves then this act of self-immolation is nothing less than an act of linguistic suicide, a pledge to burn away one’s own personal story and one’s own right to interpret stories -- one’s very subjectivity -- in supplication to a grander, overarching narrative playing at objectivity. It may not be as draconian a practice as Gerrah’s campaign of enforced illiteracy, but symbolically it serves the same purpose: a people robbed of their capacity for self-definition will latch onto the story given them, mistaking it for the only story bearing any truth in all of the world. But if the ritual of subservience forced on the natural born citizens of Sahtan is tantamount to suicide, what is done to those who have been inducted from conquered empires is nothing less than homicide. Indeed Vaatu herself makes this connection explicit a number of times: when struck by a vision of her lost homeland and a remembrance of its creation myth she wheels on the painter Velas Dagren, demanding “(if) your emperor is so kind...[as to] bring me into his home, why did he kill mine?” Later, when she returns to her homeland as an emissary, she notices how the forehead markings that her people once wore to distinguish themselves are missing and laments how in giving up this custom “they sacrifice their names...themselves.”

This is not to say that all the conquered peoples of Sahtan have willingly accepted their acculturation; in fact, for some this forced assimilation only inspires them to develop new stories and find different, clandestine ways to tell a revised narrative of their people that will allow them even the possibility of identity. For some, the stories prove useful for lending dignity if not purpose to their defeat: the isolated enclave of the blue-skinned Suirin people have taken to telling themselves that since their conquest by the Sahtan empire they are only suffered to live because their particular knowledge and talents make them the sole source of the economically and martially useful chemical known as Unweight; their elders define all the world in relation to a metaphysical “balance” that suggests their exile and their subsequent work is in fact dictated by some quasi-dialectical understanding of history. In truth, though, the Suirin chapterhouse in Sahtan is composed of the descendents of a succesionist sect that were exiled from their homeland and forced to seek refuge in the empire after they profaned their gifts; their understanding of balance, like their understanding of their own history, is a lie, a bastardization of their homeland’s guiding philosophy that no longer provides purpose but simply breaks down into a mere “system of rules, codices, chemists, a chapter-house...repeating hollow phrases they’re demanded to repeat” that enable them to better serve the empire’s interests. While some plan for rebellion, they are forestalled by their spiritual leader, the Weightless One, who claims that because she “has lied to them” by perpetuating this narrative that “(she) can’t be the one to bring (them) into the future...” And so denied the truth of their past, mired in false consciousness, they have remained for generations unable to imagine even the most modest of alternate prospects.

For the reptilian Grish who used to live on the banks of the river that runs through the Sahtan capitol, however, the narratives they allow themselves in light of their marginalization are not protective but aggressive; they are open acts of rebellion, criminal in form as well as intent, a decision that feels deliberately, symbolically provocative: with their homeland now occupied and with their people corralled into ghettoes by the conquering Sahtans, their main method of tale telling takes the form of illegal pit fights where every move of each combatant represents some element of the larger world and the officiant is equal parts referee and oracle, present as much to make sure the combatants’ blows are legal as to interpret the martial message hidden in each thrown fist and each bloody knuckle. Of all the methods of new storytelling developed in the wake of empire it is the most direct, the most literal, forged in force and demonstrations rather than in text and suggestion, and that is both to its advantage and disadvantage. While it allows the Grish to envision a better tomorrow (a possibility the Suirin’s own method of mythmaking specifically foreclose on), it is a tomorrow limited by the very nature of their storytelling to the same language of physicality that only finds expression in the occasional violent eruption, a brief flaring up of resentment that results in a crackdown, an admonition, and the further vilification and marginalization of the already destitute Grish. With recourse to no style of storytelling except one rooted in brute physicality that can only speak of possible futures but never the past, the Grish’s modes of articulation are similarly limited. Like the Suirin, like Vaatu, like emperor Arrius, like every citizen of Sahta, they are less the tellers of the tale than its conduits, playing out roles that were assigned them by an accident of birth, embodying the form of the tale that “tells” each of them in actions beyond their control. What limited ability they do have to invent new histories and imagine new futures may seem to offer an avenue for resistance to the coercive and totalizing power of hegemony, but in truth what they envision are not so much alternatives as the natural byproduct of any imperial project, defined entirely within the limits of the world given them and so destined for cooptation.

Seen in such a light, it might be said that the Christ of Dahm’s The Harrowing of Hell was doomed to fail from the start. If the story of empire is built to absorb every alternative offered to it then there can be no possibility of liberation; the work of any would-be Messiah was always doomed to be perverted the better to perpetuate the exact systems it had been envisioned to overturn. Harrowing is a development of Dahm’s work, after all, a crystallization of so much of what its predecessors have been building towards for the better part of the last two decade. It seems little coincidence (or at least a coincidence worth remarking) that while Vaatu is expressly set in Overside, its designs and iconography owe more than a small visual and cultural debt to the same Roman Empire that crucifies Jesus in Harrowing: everything from the military garb of Sahtan officers to the architecture suggests the connection. It’s as if the more crystalized Dahm’s vision has become the more his visual stylings have become subdued, sedated; despite his suggestion that he has long preferred the surreal to the realistic, his own comics have steadily trended towards a style more grounded both visually and narratively. Gone are the fantastic and the magical elements that made his work so appealingly alien, gone the grand scale conflicts that encompassed mythic dimensions and metaphysical shenanigans. If Harrowing allows itself a trip to the fantastical realm of Hell it is a Hell that has been tellingly stripped of nearly all the artifice that would mark it as such and so rendered nearly indistinguishable from the world that Christ himself only just departed. It’s as though Dahm’s attempts to expose the monstrous truth of coercive narratives has in some ways required that he himself adjust to their specific dimensions to better depict them.

And yet this shouldn’t be taken to mean that in attempting to depict the fallibility of stories -- of their vulnerability to perversion, of their potential for complicity in enabling the worst impulses of authoritarians -- that Dahm has somehow ended up becoming such a tyrant himself. Harrowing, like Vaatu, may be a fundamentally pessimistic work but it is not the pessimism of one so dispirited by struggle that they find themselves cynically siding with their opponent; this is not some cautionary tale echoing the tired-bordering-on-pretentious advice that those who fight monsters are liable to end up monsters themselves. Nor does it feel, despite its bleak ending, as if Harrowing represents some ultimate repudiation of fiction’s viability. There will always be stories and so there will always be those who seek to twist them to nefarious ends; to give up story writing in the face of that would be no better than the kind of abdication Dahm seems so skeptical (if sympathetic to) in Christ’s own decision throughout Harrowing to refuse his followers, his accusers and his persecutors any absolute definition of who he is and what he intends by his work. No, Dahm’s pessimism is rooted instead in deep love of -- in defense of -- his chosen artform, with the pitch black page and challenge of Harrowing’s ending meant not to foreclose on the possibilities of fiction so much as push these doubts of Dahm’s to a limit beyond which he will have to find some deeper development of his reining preoccupations. As of this writing Vaatu is unfinished, the various factions all on the cusp of a violent uprising that may not be guaranteed to topple the Sahtan empire but which will seems poised to transform it drastically. While it is possible that Dahm might correct course in time to arrive at a conclusion more in line with the optimistic, albeit melancholy, endings offered in his earlier projects, it’s difficult to envision any such course correction. For all he has always been experimental, playful, Dahm has also always been an artist dedicated to the refinement of one overarching preoccupation. To swerve from it now would be an evasion, exactly the kind of abdication his work elsewhere has made evident might be attractive but is also, ultimately, an undermining of the authorial responsibility he finds so challenging.