Just when you think you know who Hunt Emerson is, he’ll throw you a curveball. You likely know him as the foremost underground-style comic artist in the UK. Much of his work is adult-themed and iconoclastic. For 40 years he and writer Tym Manley called out the oddities of human sexual behavior in the strip Firkin for Fiesta magazine. For nearly as long, Emerson has leant his whimsical, often caricature-rich style, to Phenomenomix for Fortean Times. A new collected volume of Phenomenomix will be available in the spring of 2022. (For the uninitiated, Fortean Times follows in the footsteps of American writer Charles Fort, who was fascinated by all manner of unexplained phenomena. From spontaneous human combustion to levitation, from UFOs to cryptozoology, Fort collected reports of anything unusual, unexplained or fantastical. Fortean Times reports on these things as well.) Emerson has also done comic adaptations of a variety of classic books from Dante’s Inferno to Lady Chatterley’s Lover to the works of John Ruskin for Knockabout Comics.

Just when you think you know who Hunt Emerson is, he’ll throw you a curveball. You likely know him as the foremost underground-style comic artist in the UK. Much of his work is adult-themed and iconoclastic. For 40 years he and writer Tym Manley called out the oddities of human sexual behavior in the strip Firkin for Fiesta magazine. For nearly as long, Emerson has leant his whimsical, often caricature-rich style, to Phenomenomix for Fortean Times. A new collected volume of Phenomenomix will be available in the spring of 2022. (For the uninitiated, Fortean Times follows in the footsteps of American writer Charles Fort, who was fascinated by all manner of unexplained phenomena. From spontaneous human combustion to levitation, from UFOs to cryptozoology, Fort collected reports of anything unusual, unexplained or fantastical. Fortean Times reports on these things as well.) Emerson has also done comic adaptations of a variety of classic books from Dante’s Inferno to Lady Chatterley’s Lover to the works of John Ruskin for Knockabout Comics.

Of course, you could easily not realize that he was a contributor to the look of the Two-Tone movement of ska music in the late '70s and early '80s. That hip, racially ambiguous icon of ska music, The Beat Girl, is his design. Many of his posters and cover art for the band The Beat were featured in a retrospective in Coventry in 2021. He has continued that work, designing all of the art for The English Beat’s 2018 Here We Go Love!

He also does occasional non-comics, non-commercial art - like participating in the 2000 installation art piece "Intervention", and currently designing something special for a local landmark.

And when you think you’ve pinned Emerson down as an artist, remember that for the last 16 years he’s been drawing for that long-running UK institution of kid’s comics, The Beano. He reprised classic strips like Little Plum, drew his own original strip, Ratz and now does the very popular Make Me a Menace page. His first children’s book, Moby Duck, with Ian Billings, will be out in 2022 as well. But wait, before you think you know all about him, read on to hear about his life as a musician, a tai chi instructor, and his involvement with a wide variety of programs to help youth and community.

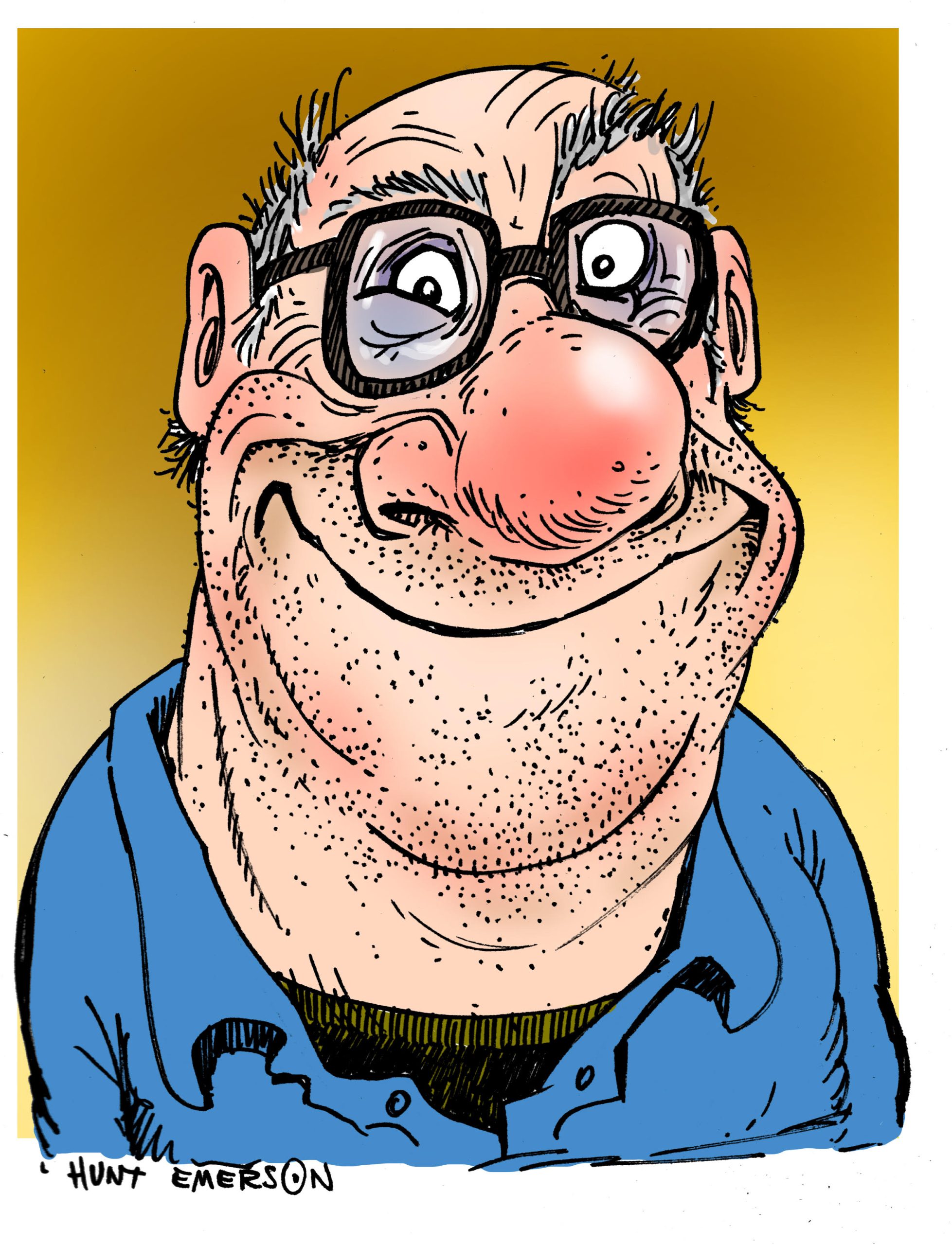

Of course, the thing that makes all of this possible is a fundamental pragmatism that comes from his working class roots. Emerson displays an unwillingness to take himself, or his work, too seriously. While he is quietly proud of some of his accomplishments he’s also generally self-effacing. We spoke at length by phone. I enjoyed our conversation and found him delightful. I hope that you will as well.

-Tasha Lowe-Newsome

* * *

Tasha Lowe-Newsome: How are you? I am sorry to hear that 2021 has been on the difficult side.

Hunt Emerson: Oh boy has it. It’s been really something. It’s been a strange time. I was diagnosed back in October of 2020 with colon cancer. It was caught early, it wasn’t big and it was an easy operation so they managed to get me straight in for surgery. Well I say straight in, it was January. They removed it. Of course this was during the pandemic and lockdown. I was, oh, seven or eight weeks recovering from the operation and then I was on for six months of chemotherapy, which was not great. It wasn’t terrible, but it was pretty bad. (Laughs) Towards the end of that is when we got married. We got married on August the 3rd.

Congratulations!

Thank you. We had a tea party, in a hotel with about 25 people there and about half a dozen people came down with COVID, including me. So I had another few weeks of up and down. It didn’t go well with the chemotherapy. I wound up in hospital for a week. After all of that I’m clear now, I’m clear of the cancer and the COVID. I’m still in what they call a vulnerable sector. I have to careful, ‘cause my immune system’s not what it should be yet. So I have to keep it careful.

Unfortunately chemo takes down the cancer, but can make immunity weaker in the process.

That’s right. But it’s one of those things. It’s happened. I’m waiting to see what’s going to happen this next year.

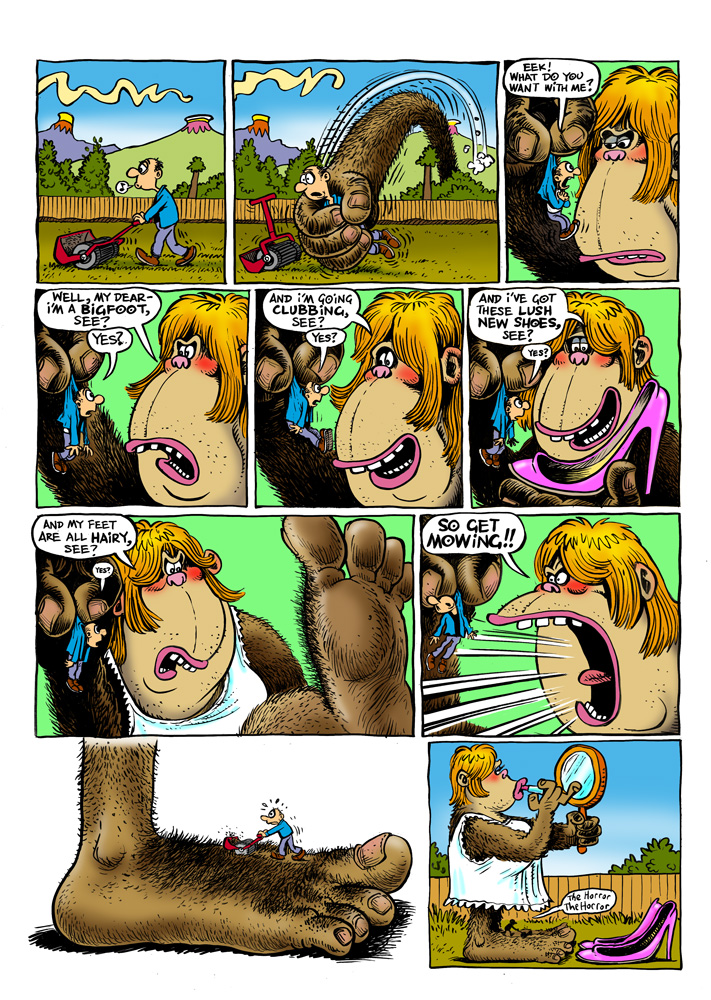

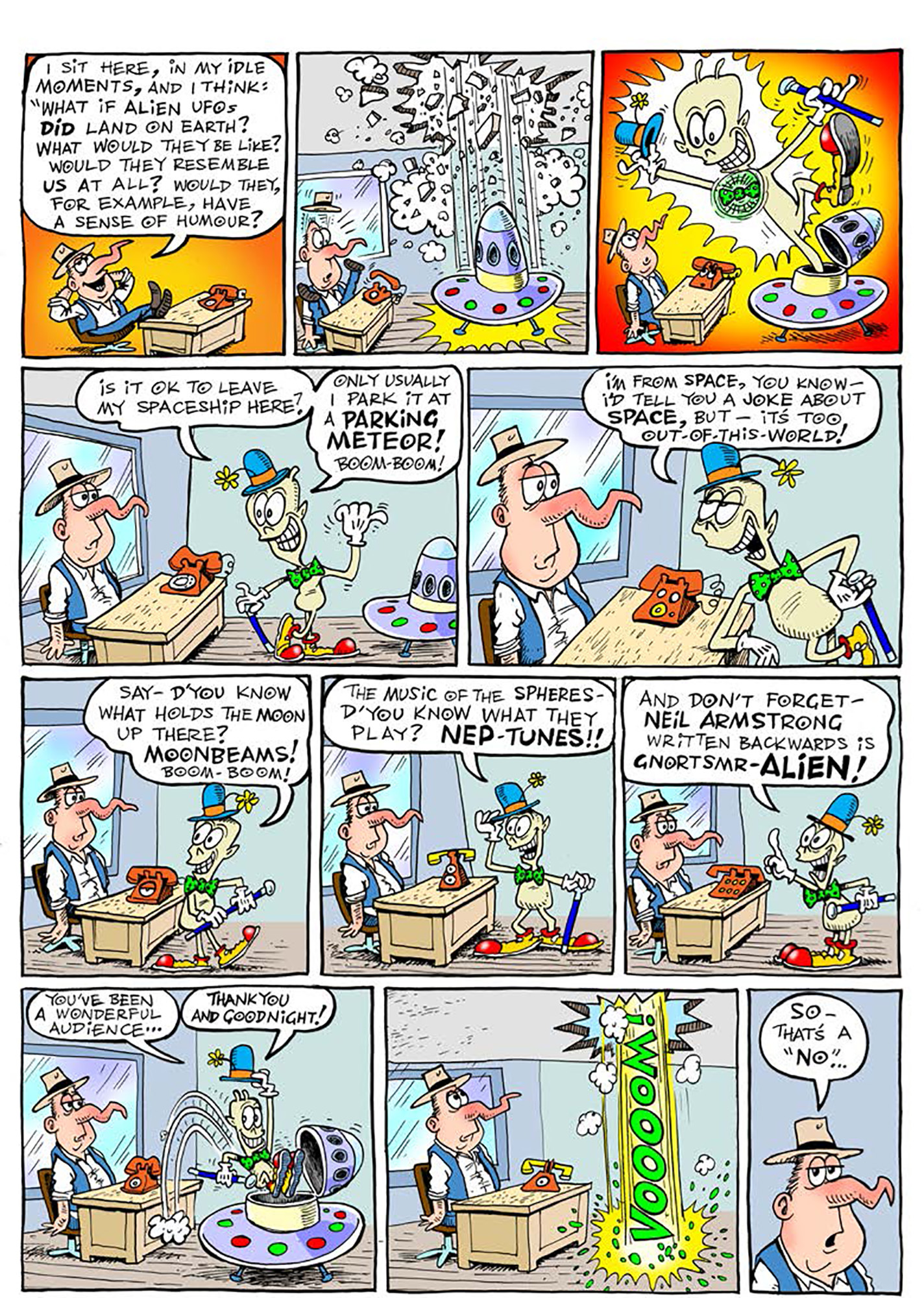

Let’s start with your most current project, Phenomenomix. This collects your work from the Fortean Times comic of the same name.

The Kickstarter has gone very well. We got the amount we were looking for, a little bit more as well. We’re now putting the book together for print. It’s going to be printed in Lithuania. The whole book is there. It’s laid out. I think we’ve finished editing it now. We, this is Tony Bennett and me. He’s been going through it with a fine tooth comb. I’ve got to do covers, but we’re waiting for information from the printer about some templates for design. So we’ll get the covers done. They’re designed; they’ve just got to be laid out. Then get it off for printing. Then sometime, I reckon, in the end of March we’ll eventually get them back. It’s going ok. I’ve got the various rewards to do as well. All of the bits and pieces.

Kickstarter is a good thing to do. It seems to work well. But I don’t think I’ll do any more. (Laughs)

Had you done any before?

I’ve done two before this, yes. I did Calculus Cat, in 2014. Calculus Cat was originally a book in the '80s, of strips that I’d drawn over the past years and collected together, about Calculus. Since that book was published I’d drawn quite a lot more, so we put them all together and made this new Calculus Cat, which is the collected edition. It was "Kickstarted" and that came off ok as well.

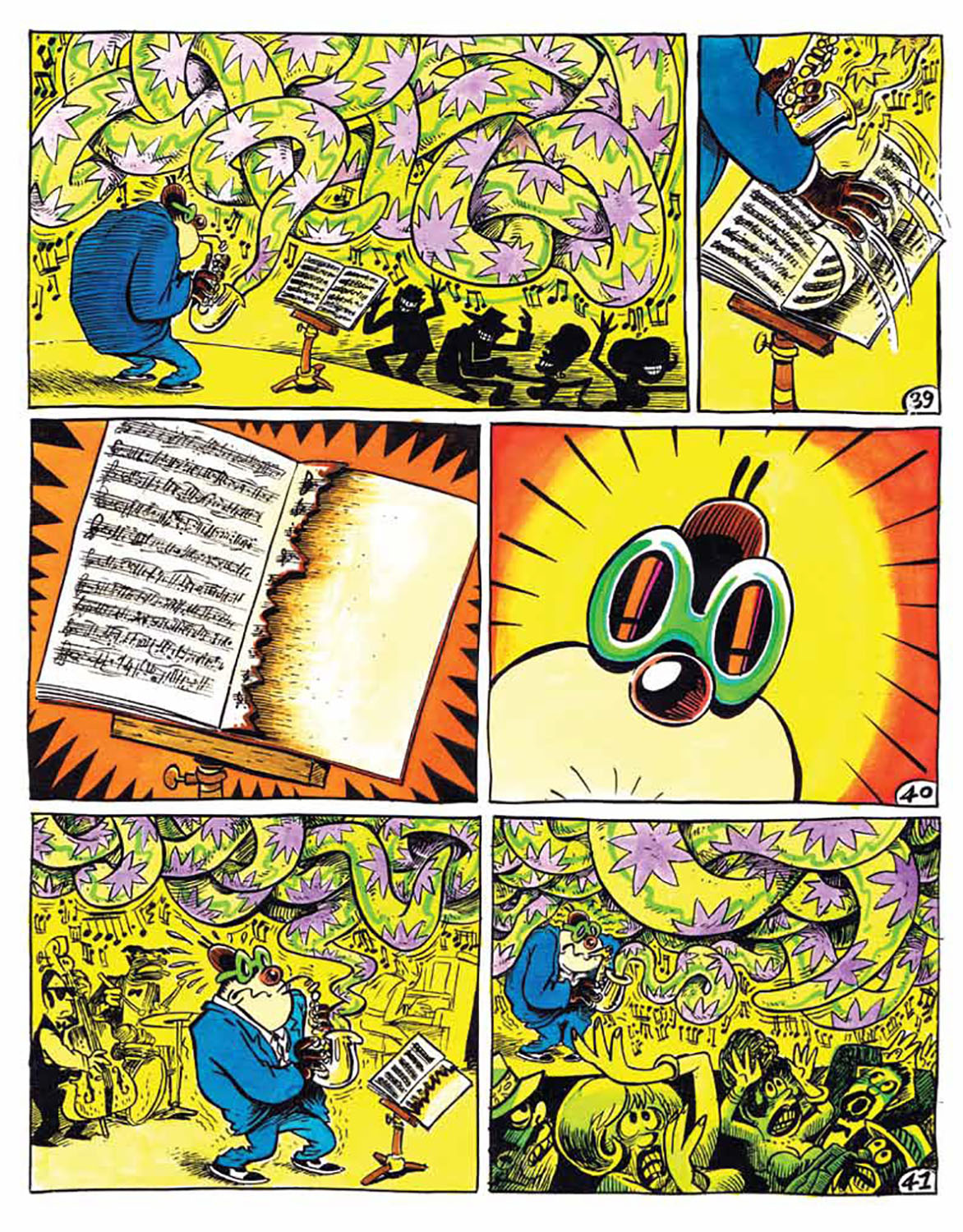

Then we followed that up with Hot Jazz, which was the same sort of thing with Max Zillion, the jazz saxophone player character that I draw. That almost worked. We had to chuck in 1200 quid ourselves in order to make it work, but there you go.

This time around I wasn’t sure it if was going to work at all. For a long time I thought, “It’s not going to work, it’s not going to work.” But in the end it took off and we got the money we wanted. But I’m not going to do any more. (Laughs)

It is a lot of work. I’ve not done one myself, but I helped out with someone who did one. And it was kind of a crazy amount of stuff to do.

It’s hard work. Yeah.

It sounds like one of those love/ hate relationships. You love that it works and hate how much work it is.

Some Kickstarter projects that people do, especially on comics, were they get phenomenal amounts of money? I can see how that’s worth doing because it’s actually giving people a living doing it that. It must do, the tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of dollars that come in for them. It hasn’t worked that way for my projects. But we do get a book. It means we publish the book and the book will be in the shops. So it’s like a regular book as well as a Kickstarter project. But that’s all part of the Knockabout business, which you know, doesn’t make a lot of money.

I’ve always appreciated Knockabout. Back in the day when I worked in a comic store and did ordering it was always a go-to for me.

So what are your favorite Fortean subjects, both to draw and in terms of your own interest in the subject matter?

I’m interested in cryptozoological stuff. Strange animals. But you know it’s just whatever comes along really. Doing a page every month for Fortean Times, I mean I’ve said pretty much everything I’ve got to say about UFOs and crop circles and things. It is difficult to come up with new ideas. Sometimes I’m banging me head against the wall for two days trying to think of something. But something always comes. I’ve only actually missed about two or three issues of the magazine. One was because they oversold advertising space and the other two was because I was ill. I’ve managed to get something every month. Working with Kevin Jackson helped. For about five or six years he wrote the strips.

I don’t know. It’s a good subject to work with, the whole lot, because it’s so bizarre, really. You start to see everything through that sort of light. So I was reading today about a guy who had written a definitive book about cricket the sport. And he’d also cut his own right leg off, in the bath. (Laughs) I thought, “WHAT?” I said to Jane, “Did you read this?” And she said, “Yes, I didn’t want to point it out to you, I wanted to let you discover it yourself.” She’d had exactly the same reaction. “Cut your own right leg off in the bath to prove it could be done. What?” It’s true.

Perhaps he was trying to one-up Van Gogh.

That’s the kind of news items that are really interesting, isn’t it?

I’ve enjoyed lots of stuff in the Fortean Times over the years. I was always fascinated with the “airatarians,” or ”breatharians:” people who claim that they can receive all of their nutrients from the air and the sunshine.

Oh right. Yes.

It was always a little sidebar someplace, “Reporting another death of an airatarian.” (Both laugh) It seems sort of obvious that it might not work.

The nice thing about being “a Fortean,” if you like, is you are not required to believe or disbelieve anything. I like to be able to suspend belief. I go to Fortean conventions, when I can, when they happen. There’s one going to be happening in April 2022. It will be the fifth of them. It’s called the “Weird Weekend North” and it’s two days of crazy people talking about crazy things. I get to sit at a table and I draw people. They come and sit in front of me and [I] do a caricature of them, you know. But I get to listen to all of the lectures, all of the talks as well. There is some bizarre weird stuff. I just go up there and suspend disbelief. I’m quite happy to hear all of this stuff and take it all in for the time I’m there. Because it’s fun, interesting.

Absolutely! The advantage is you probably hear stuff there that leads back to more strips to draw.

I try to, yes. I’m always looking for stuff.

Can you tell me a little about Shujaaz, a comic-based endeavor that you were somehow involved with in 2009 or 2010? It seems like a really interesting project.

It was, it is. What happened was a guy from Nairobi, Kenya, contacted me - Rob Burnett was his name. He’d worked with NGOs and also with independent media. He’d been involved in a very popular soap opera that ran in Kenya. He wanted to start this project that involved a comic. He didn’t know where to start with, because there were no comics in Kenya. He found out about me. I think somebody recommended me. He got in touch and said he wanted me to come over to Nairobi and run some workshops with African artists and writers. So we did that. I was in Kenya for three days. I did these workshops with some young people and some artists and writers. It worked out well.

Do you know about the way that they finance things over there? Using text messages and telecoms and SMS? It’s like a guy comes from the country into the city to work. He has to send money back to his family, to his mother in the country. And it’s too far away to hand carry and too dangerous to send anything, so what happens is he pays a small amount to Safaricom and they give him a pin number. He texts the pin number to his mother and she goes to the local grocery store and she gives them the pin number and she gets money. And that is how they are financing not just that sort of domestic thing but all sorts of things. Their whole lives are starting to be run like this.

Now what Rob was doing was setting up an organization that was going to help young people, in particular, to find ways to run their lives and make money and working and taking care of practical needs. He wanted to do it through a comic that would be distributed free by the Safaricom. When you sign up for Safaricom and use the texts, you’d get a copy of the comic. Or it was given away each week in the big national newspaper. The comics would be giving hints and tips to young people, like how to grow spinach in a sack in your backyard or how to paint your chickens pink to stop them being taken by hawks. How to raise rabbits and use them as a business. How to set up a business. How to set up a school’s council, how to talk to and approach our local council and find out if there is money available. All sorts of things like this. It involved young people; in particular, texting each other and sending messages to each other, in the comic. The comic had four main characters in it, but the main one was DJ Boi who was this young guy who supposedly ran a pirate radio station from his backyard and had all these contacts, including the other characters in the comic, and lots and lots of real people. They text each other all of this stuff the whole time. It’s kind of a big communications thing, helping each other out. And it works. It actually helps. It has improved the lives of these young people.

The radio station part of it, they actually run a radio station. At the time it was from Rob’s backyard. It was a legal sort section of the National Radio Station that sounded like the pirate radio. And people would be listening into this every week. It was partly the ongoing stories of the people in the comic and partly all these young people passing messages on to each other. And all this is happening in Sheng, which is the local street language. It’s partly Swahili and partly English and partly another local language. You know it’s street slang.

They invited me over to show these people how to start making a comic: how to start thinking about making characters and designing things and how to start thinking about writing stories in a comic way. And it took off. The first run was a million copies. They reckon that about seven people read each comic book, so there’s like seven million readership. (Laughs) And it’s gone on for several years. It’s now become a franchise; they do something in Tanzania as well.

It was nominated for three and won two international Emmy Awards for its work. And it’s become a very much bigger business all around - linking people through their mobile phones. It’s a sort of 21st century way of operating things. I don’t fully understand it, because we don’t have to do this, but this is how they do it over there.

And I’m so proud to have involved in setting this thing up, even though I’m not in it. I don’t have any artwork in it, or anything like that but really pleased to have been part of the start of it because it’s become such a big thing over there.

It’s fascinating. I understand that even though it started as the comic it has become multi-media platform. I’ll include a link for folks who want to learn more.

I was in West Africa one time, many, many, many years ago.

It’s a strange place, isn’t it?

It is, but so vibrant.

They say if you once taste the waters of Africa you can never be satisfied by any others. I think I see what they mean about it, you know.

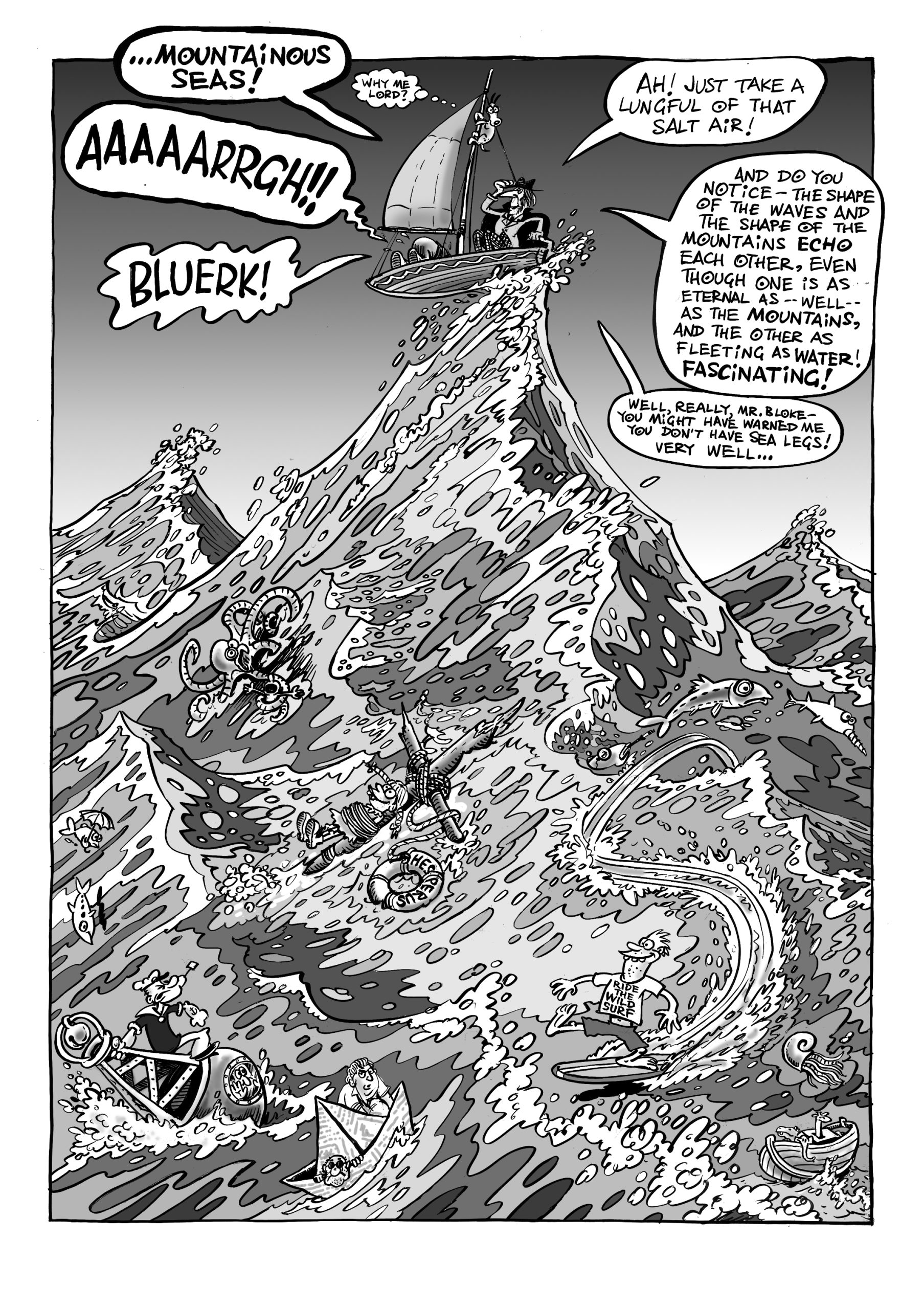

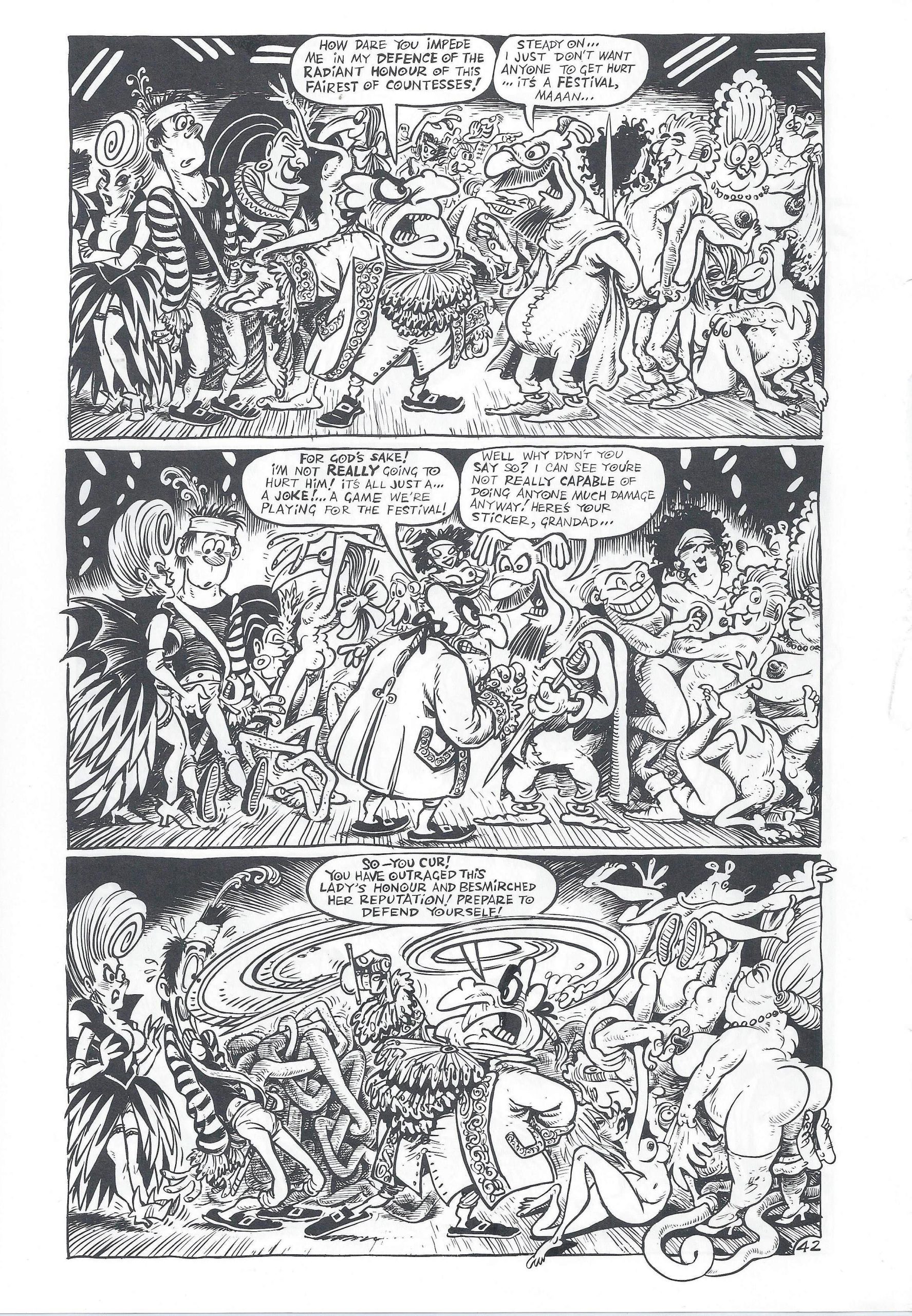

I’m going to reel you back to Britain, and a very English Englishman - John Ruskin. How did Bloke’s Progress come about? I see that you did some other things with the Ruskin Trust.

This is Kevin Jackson. This is my good friend Kevin, who died last year. This is something that happens, as you get older - people start dying around you. I’ve had quite a few deaths.

I’m sorry to hear that.

2019 in particular was a very bad year. Well, Kevin Jackson was a writer and a kind of man of letters, if you like. In the old-fashioned sense. He was a journalist and a critic and a bit of a filmmaker. He was a bit of a renaissance man. And he wrote essays and things.

We first met when I published The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. And we had a party, on a boat, on the Thames to promote it. And I had dress up in 18th century costume, which was quite nice actually, knee britches and a fancy waistcoat. I had an inflatable seagull on a rope around me neck. It was supposed to be an albatross. Well Kevin was reviewing for The Independent newspaper at the time, so he got on the guest list, and came along as a critic. We met there.

I didn’t come across him again until much later, when I had a call from somebody or other from the Ruskin Foundation. They were wanting to do a comic. Kevin was going to write it but he would only agree to write it if he could have me as the cartoonist. Was I interested? So we got together. The Ruskin Foundation wanted to make John Ruskin’s work more available to young people in particular. They thought a good way to do this was with a comic. We got together, discussed what was going on, how we’d deal with this. We did the first comic, which was called How to Be Rich. Which was based around John Ruskin’s book on economic and political philosophy called Unto This Last. And well it worked. It was done as sort of a private publication. It was distributed in the North West of England, which is where Ruskin lived at the end of his life. Where Coleridge was too, of course. And it was distributed to schools and youth organizations and to prisons as well. It went down very well. So we followed it up a couple of years later with another one, which was called How to See. Which was based on Ruskin’s ideas on perception. Again, same sort of deal, it was for the North West of England. There was always going to be a third one, which was How to Work. Which would sum up his political philosophies.

Eventually we did that, along with the first two as Bloke’s Progress. So, Bloke’s Progress is like a trilogy of the three comics. That was done through the Ruskin Foundation and Knockabout Comics, a 50/50 thing. Kevin wrote ‘em. I drew’ ‘em. It was an odd subject. I didn’t know anything at all about Ruskin to start with, but I’ve become quite a Ruskonian scholar. Not scholar I guess, but follower. Ruskonian? Ruskinian? Ruskovite? It’s fascinating stuff. Odd subject for comics.

One of the things I have loved about your work is the juxtaposition of sources and subject matter. I think people forget how really racy some of the classics are, then to see your take on it and realize - that’s really more interesting that we thought.

Well these things are interesting, aren’t they?

I’ve got into doing these things because we did Lady Chatterley’s Lover all those years ago. That was to cash in on the fact that Knockabout had been through a censorship proceeding in the courts and had finally got clear of it, and won the case. It was a kind of a celebration of that, because Lady Chatterley’s Lover had been through a similar sort of thing back in the 1960s. And also, quite importantly, the book had just come out of copyright. (Laughs)

There is nothing like public domain.

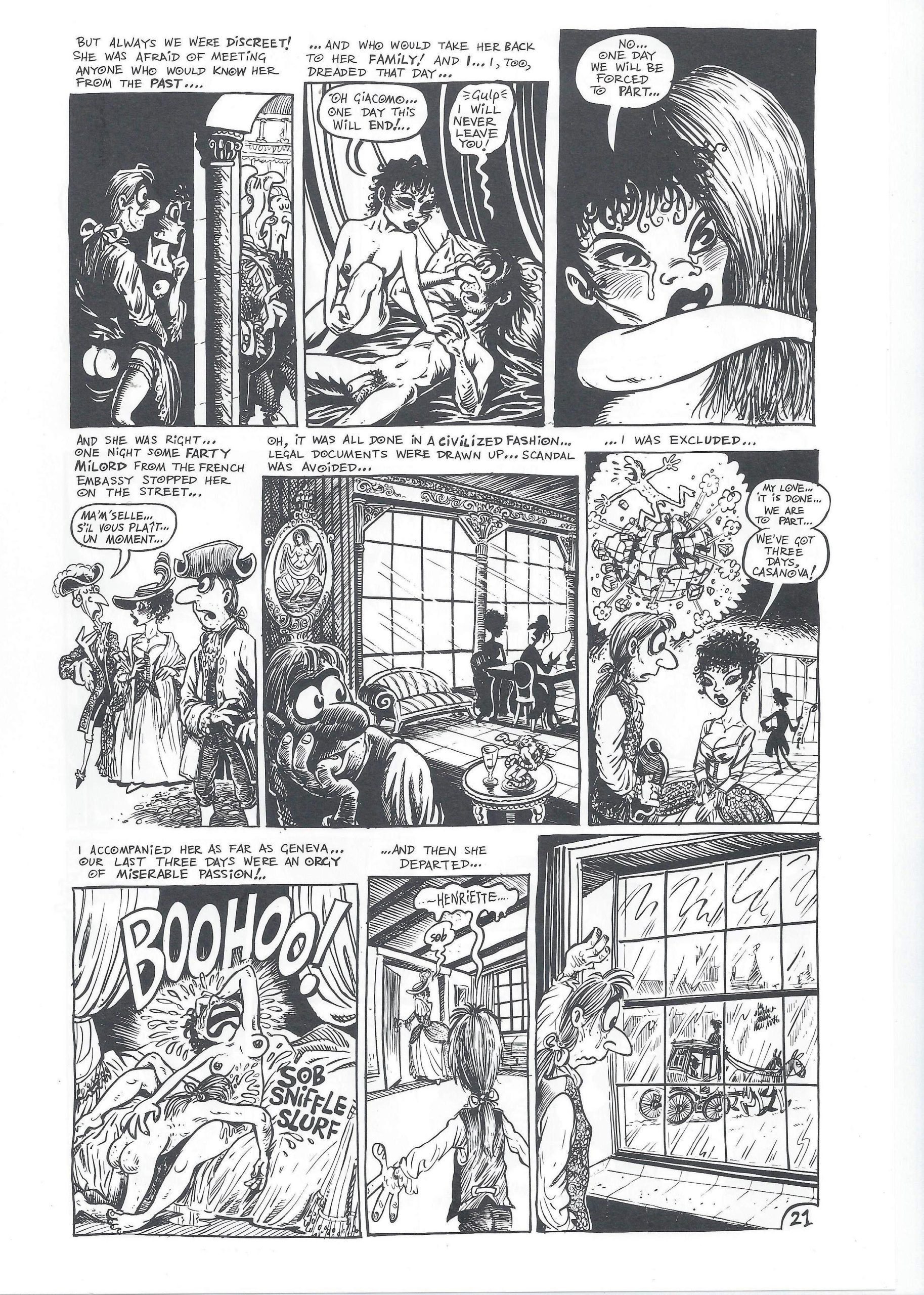

Absolutely. So, we did that and it was quite successful. Then we did Casanova [Casanova’s Last Stand] which I thought was a much better book, but it wasn’t as successful. Then, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, which is still selling. We’ve done three editions of that. Then Dante’s Inferno, which was also with Kevin Jackson.

Kevin was a man who had many subjects around him. Like Ruskin was one of his subjects. He had done the “Grand Tour” throughout Europe, the way that Ruskin had. Kevin is possibly the last person to have done that tour.

Dante is another of his subjects. He suggested that we do it. I went down to his house in Cambridge and he brought out about 35 different illustrated versions of Dante, which was just amazing. Had a very nice evening going through those.

Another of Kevin’s subjects is the occult. So he was writing all of the strips for Fortean Times that are now in the Lives of the Great Occultists. The latest book that I did. That was Kevin, wrote those.

I’ve forgotten where this started now. (Laughs)

It started with Ruskin. So we’re going from the sublime to the ridiculous - you started working at The Beano, which seems like coming full circle in a way. I know that Beano is an institution in the UK.

'Tis an institution, for sure.

You started in 2002 with Little Plum or something else?

Well you draw what they tell you to draw, basically. (Laughs) I talked with The Beano quite a few years ago; they’d approached me about working for them. It didn’t work out then, as much as anything I was too busy with lots of other work. And I didn’t want to get involved with kids’ comics work. I knew the guys, but they approached me again in 2002 and said did I fancy doing something and I said “Yeah. How about Corky the Cat.” Which is a character in another comic. They said “No. We want you to just work on The Beano.”

I don’t know what the first one was, I did a couple of strips for them but then we got into doing Little Plum, a comic that originally started in 1953 [issue 586 of The Beano, 10 October 1953] by Leo Baxendale, the great cartoonist that did so much early comic work for children in this country. That was fine. I had fun doing Little Plum, but as I say they change you around, they give you different characters to do, so after a while I was put onto something called Fred’s Bed, which I hated. But I did that for a year or so. Three Bears I was doing now and again. Then I invented one called Ratz.

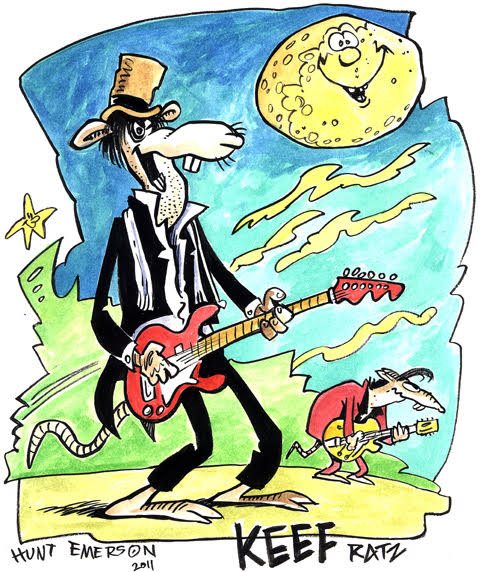

That was an idea Alan Digby, the then-editor of The Beano, and I came up with more or less on the spur of the moment. It was how they did things then - not much planning went into it. The Beano has become more businesslike now. So, he and I were chatting on the phone, and I said, what about some rats that live under Beanotown? He said, “You could do a Keef Richards Rat” - and so Keef was our first character.

So Ian set me loose with Ratz. I immediately recruited Laura Howell to make it work. Laura was just breaking into comics, and I was introducing her to DC Thomson. She became the first female cartoonist on The Beano since it started in 1937. She’s a brilliant comics talent who is now one of the main Beano artists, running Minnie the Minx.

On Ratz, she drew some, inked some of my pencils, I think, but mainly she wrote them. We had good fun with the Ratz. So, Laura and I came up with Herman Vermin, Rod Rodent, Rasta Rat, Ratti Patti, Rubella Rat and Malaria Rat... there were some others. But they were never very popular with the readers, and now they’re consigned to oblivion along with Little Plum. There are a lot of big changes that went on in The Beano in the last few years.

I’m now doing a thing, which is on the back page of the comic, called “Make Me a Menace.” What happens is that parents, or the kids really, send in photos of themselves along with their menace name. So you get “Typhoon Tommy” or that sort of thing. And they get a page drawn about them as the character and I draw the page. It’s very popular, as you might imagine. It’s weekly, so let me just check this, it’s a weekly comic and I’ve just done number 345. So it’s been running that long. It’s quite good fun, you know.

That is very cool. So the kids are sort of like members of the Menace family. I have no doubt that 15 years from now someone will be interviewing the best new UK cartoonist and they are going to say that they became a cartoonist because you drew them as a Menace and that page hung on their wall for years - inspiring them in the way that Leo Baxendale inspired so many people.

Haha! That’s a funny idea! But I can go with it. I think it’s entirely possible. I’m aware how important it is to the kids involved - I got my great nephews into a page (In-A-Minute Isaac and Not-Now Noah), and I know the kudos they got at school! And we regularly get letters from parents whose kids have been Menaces, saying how much they appreciate it. One time, a parent sent six bottles of champagne for the writer, editor etc. and me - we drank mine at our wedding - it was Bollinger!

[Dear Reader, I am going to make an aside at this point. The Dennis the Menace of The Beano is in no way related to the Hank Ketcham creation that has run in U.S. newspapers since March, 1951 and spawned both TV and film adaptations. Also beginning in March of 1951, The Beano’s Dennis the Menace was created by George Moonie and Davey Law. The Beano Dennis is an archetypical bad boy who never repents. Outside the UK the strip is known as Dennis & Gnasher. Gnasher is his equally bad dog. -Tasha Lowe-Newsome]

Working for The Beano, it’s a job, it’s regular. It doesn’t pay fantastically well, but it pays every week. But it’s a great privilege to work for The Beano, because it’s an institution in this country. I used to read it when I was kid and it had already been going for 20 years then, in the 1950s.

But as I was saying they’ve changed it a lot in the last few years. In that they’ve got rid of all of the kind of extraneous funny animal characters and things like this. Now they concentrate on Beanotown. And all the kids [that] live in Beanotown are the characters in the comic. And there are a lot of the traditional ones, like Dennis the Menace and Minnie the Minx and Rodger the Dodger and um, Billy Whizz, the fastest boy in the world. But they’ve also introduced quite a lot of others as well. So there’s a joke shop run by an Indian family and their comic adventures. And there’s a little girl who’s a good inventor, she invents amazing things, she’s in a wheelchair. It’s not all diversity, but it’s a lot more diversity than used to be in it. They all link in together. All these characters appear in each other’s stories and sometimes they appear in my page with my characters based on the kids who send in their photos. So the whole thing has become very unified. And it’s really worked. ‘Cause their circulation is rising in a time when kids’ comics circulation is lousy. They are getting more readers all the time. It’s great.

That is wonderful. It’s good to hear. It sounds like some of the changes to The Beano–how all of the characters are in each other’s stories and it’s very unified–is a little like what they are doing in Shujaaz - how those characters also interact with each other and the readers. In a way with The Beano is interacting with readers through the "Make Me a Menace" page.

That’s a very interesting observation, Tasha. The two things–Beano and Shujaaz–are so totally different, but linked by their readers. I don’t know where Shujaaz are now - I don’t see the magazine, but I know there’s lots of online interactive stuff and the whole enterprise has become a successful community development program.

The Beano is an entirely commercial enterprise that is being developed into a “21st century product” using the wealth of characters they own. That sounds like a PR blurb. The Beano studios that manage all the changes are very clever, in a non-devious way. They are changing a lot of characters - I was reading a chat-stream today from Beano artists, grumbling that no-one had told them that Herbert in the Bash Street Kids, formerly blind as a bat with comical results, from now on could see perfectly clearly with his specs, or that Smiffy, previously bone-stupid, now has a “different approach to the world”, leading to all sorts of surreal occurrences around him. Which all, to me, sounds admirable!

I’ve always found your work to be funny and ironic and observant. There is sometimes subject matter that I might not hand to my six-year old nephew, but…

You have to realize that all through me life, all through me career as it were, the main motivation has been paying the rent. I’m rather insecure in that way. I’m terrified of debt and money and things. My main motivation has always been to be employed. There’s never any leisure time. Time to do just things I want to do, because I have to be working all the time. Thus I take on whatever is offered basically and I don’t see that I have any room to make moral stances about things like Firkin. I’m being offered work here. I can cope with it. Like I say, “It’s only a comic. It’s not that important.” But so long as I’m employed that’s ok.

It is interesting that you say that. Because in your previous Comics Journal interview you talked about being pushed by your dad to “Be an engineer.” Being a creative person you wanted to avoid the nine-to-five, that sense of drudgery and going in and doing the same thing every day, and yet the work ethic certainly is retained. I think you avoided the frying pan but maybe went straight into the fire, (Emerson laughs) in terms of how much work is necessary in a freelance life, as opposed to clocking in five days a week. It is a choice I see a lot of people in the arts make. Touring musicians come to mind.

It means that you are working all the time. You never actually stop thinking about work, even in your down time. You are aware of all the time of “why aren’t you working?”

This leads to the question I had next. You continued to do Firkin and Phenomenomix and The Beano. That seems like an awful lot of regular work. Am I missing any other place where your work is seen fairly regularly at this point?

Firkin’s finished now. They closed down. Nothing to do with Brexit or the pandemic or anything, they [Fiesta magazine] just basically closed the business in 2019. The last Fiesta magazine was published in January of 2020. So I stopped drawing them at the end of 2019. I mean, you know, it was a sex magazine business, who the hell was buying the things? I have no idea who reads those magazines? It was a few months before it would have been 40 years. Fortieth anniversary. It’s a shame. It would have been nice to make 40 years. But we didn’t quite. Firkin’s gone now.

Because I’m in the states and I don’t even know if Fiesta ships here, I’ve always encountered Firkin in the Knockabout editions.

The best collection is the big collection that’s currently on sale, just called Firkin. I think Firkin’s hilarious, to be honest.

I do too.

It’s never had any pretense to be tasteful.

One of the great things about Firkin is that sex is generally so unglamorous in it.

I go back and read them and I find myself roaring with laughter to be honest. I don’t know how Tym Manly managed to write them all, all those years. Tym was originally an editor of the magazine, but that was back in about 1968. He was a freelance writer for most of his life. He edited a mountain biking magazine and somehow or other he found himself writing Firkin. He doesn’t write any other comics. But just as I’ve done all those years, 40 years of them, he was writing them. Incredible. I mean drawing them is basically sitting down and getting on with it. But writing them you have to come up with the ideas as well. God help us. (Laughs).

So you were saying about regular things. There aren’t really any other regular things I’m appearing in. I’m doing The Beano every week, Fortean Times every month and so that’s five pages of comic every month, and before Firkin finished that was more. It was regular output. Plus whatever else comes along.

That’s a ton of work. I just wanted to be sure that I wasn’t missing any current work. A few years back you did some work with Ahoy Comics.

Yeah. Once again they got in touch and said would you like to do this work based around Edgar Allen Poe? So I did two series around The Black Cat [story]. It was great.

I set myself limits when I started doing that. The rules were that there had to be practically no words and they all had to end with Poe getting a kick up the pants. I don’t know if I could have done any more. Gone as far as I could with it. But the other thing was that what Ahoy Comics seemed to be into, certainly in those comics was horror. And I’m not very interested in the horror side of things. I like the funny side of it. The gory horror stuff doesn’t get me I’m afraid.

Knockabout was started by Tony and Carol Bennett, but now it is just Tony. And you’re still working with him. The new book, Phenomenomix, is coming out from Knockabout. When will it be available for comic distribution?

Round about the middle of 2022. There’s the Kickstarter edition, which is hardback. And then all of the rest of the print run will be in softback. Those are the ones that will go to the shops. I believe that Tony has already started the marketing process, however it works. (Laughs) I have no idea how it works. It’s Tony’s job, isn’t it?

What was handy about doing it–and for [the] Calculus Cat and Hot Jazz books–is that by doing it with the Kickstarter you get a nice quality product for the Kickstarter backers. Something special for the backers, but we also get a regular book to put on the bookshelves and that continues to sell until the print run is sold out. Several years. And it’s part of keeping the business going. New publications. Because of the Kickstarter process, it’s already paid for so whatever we get from selling the books, that’s where the actual profit comes. The profit doesn’t come from the Kickstarter. I mean I may come out of with a thousand pounds in the bank for me trouble. But the profits come mainly from keeping the books selling. It’s a funny old business. I’m nearly out of it now, anyway. Semi-retired.

You keep saying that. But then I look at the output, it doesn’t sound all that retired to me. I suppose compared to what you’ve done in the past…

One of the things that happened last August was that Jane retired from work. Part of my life had been getting up early, 6:30 in the morning, in order to run Jane to work every day. Then I tend to work best at night. So I’d be working on ‘til midnight or 1:00 in the morning. When she retired I stopped having to do the early mornings and both of us realized just what a lot of strain we’d been putting ourselves under for so long. It was nice to have a bit of down time now and again. Things are at a more relaxed level. Although I’ve still got work to do it’s not so frantic.

I’m sort of starting to try to be a bit more choosy about what I say yes to, rather than saying “yes” to everything. Though that’s a difficult habit to break. ‘Cause one of the things about being freelance, as I’m sure you know, is you say yes to everything, because they might not come back again if you say no.

Definitely. I’ve found myself doing blogs for business consultants or writing about nude skydiving.

I find myself doing illustrations for the website of a guy who sells clips that hold garden fences together. Yup. It’s true enough.

Ah the joys of freelancing. For people who are familiar with your work, what about you personally would be the most surprising?

Probably that I’m very ordinary. I’m not exactly suburban, but a lot of me life revolves around home and the neighborhood. Nobody that I know reads my comics. (Laughs) Fortean Times, for example, quite a lot of people read that, but not anybody in my immediate circle. I do the comic, I send it off to the magazine and nobody’s ever seen it ‘round here, that I know. But they all know what I do. They know that I’m a comics artist, that I do produce this stuff. It’s just not a part of their lives. Hence, apart from when I’m working it’s not part of my life either, really. I suppose.

That’s why getting involved in community work is quite interesting. It does give you a kind of connection to the community, with your work, with my work anyway. The frustrating part about doing community work is that it always has to be with workshops for kids. (Laughs) They never just give you the money to do something. It always has to come accompanied by a program of children’s workshops. I don’t care much for doing them.

I’ll tell you something I’ve got going, which is going to be for the future. I’ve been asked to design a window for the local parish church.

You buried the lede there. That is something that people who only know you through the work might be surprised to hear. That’s fabulous, tell me more.

I don’t know how much you know about English industrial history, but where I live is one of the cradles of industrial revolution, in Handsworth. Matthew Boulton, James Watt and William Murdock, the engineers and entrepreneurs of the 18th century, they lived and worked around here. Our local parish church was known as the Westminster Abbey of the industrial revolution, because it is where a lot of them are buried. It’s in the neighborhood. It’s a beautiful church. We’ve got a very dynamic vicar there now. One of the windows is blank. It doesn’t have any stained glass in it, so he asked me if I’d like to design something for it. So I’m going to be thinking about that in this coming year. Now that’s something that’s going to be there for a long, long time, so it’s got to be right, you know. It’s going to take quite a bit of work.

I can’t wait to see what you come up with. Do you have any pets? Cats? Dogs?

No. Not now. I’ve had cats several periods through my life. When Jane and I first started living together-- in fact before that. Where she was living she had mice. Everybody kept saying, “Get a cat, get a cat.” Then one day John McCrea, - you know, John McCrea the artist. I’ll talk to you about him in a minute. He’s a neighbor. He came ‘round, he’d been to pub and picked up a stray cat outside the pub. He came round and said, “Here you are, here’s a cat. It’s a male cat. It’ll be fine. Yeah.” So the cat came in, caught a mouse. Jane never saw any more mice. But a few days later the male cat had kittens. (Laughs) And before we could get it neutered it had another lot of kittens. So at one time Jane had 14 cats in the house. One of her rooms they just partitioned it off with cardboard boxes and made little pens and mazes for the cats and all the local kids would call on their way home from school “Can we see your kittens?” She found homes for most of the kittens, but she wound up with two kittens and the mother cat. When we moved into this house they came with us. And they were with us for quite a lot of years. But eventually they passed away. Sadly. We decided we didn’t want to have any more after that. Partly because it frees us up to go away if we need to. Also because we didn’t really want to have any pets where we were going to die before they did. It’s not a nice thing to happen. So we don’t have any pets at the moment.

I’ve never had a dog. I like dogs, but I never had any. Jane’s daughter has seven dogs.

You have dogs by proxy. What got you into tai chi?

Well now, let’s see about 20 years ago or something, there was a class running. Quite [a] few of me friends joined and I joined as well. I’ve been doing it since then. The guy who was teaching the class had to move away. We didn’t have a teacher for a while, but we kept renting the hall, just going along and doing it. We were all part of a kind of Midlands-wide group called Kai-Ming, which means “open mind”. And the guy that runs that was kind of my chief instructor or senior instructor he said to me, “Look, just start running a class, we’ll train you up properly and make you into an into an instructor.” And that’s what happened. I did the training over a year and got qualified and ran that class ever since, until fairly recently. About five or six years ago, I started taking on some of the other classes for money, which is rather nice. Working with lots of old people doing tai chi. I really enjoyed doing that. What stopped me doing that was being ill and the fact that the classes closed down with the pandemic. But when I got ill I just wasn’t up to doing the work any more. I’m not an instructor any more, but I still do tai chi, though not every day, I have to admit. Who does? It’s a good system.

If you go on to YouTube and put in Kai-Ming–with a hyphen–you’ll find Mark Peters, who was my senior instructor. You’ll find lot of him. It’s his business.

You have also taught other things. It sounds like the kids’ stuff isn’t your favorite. Do you ever get a chance to teach at colleges or universities or older groups?

I’ve done quite a lot of teaching in various ways over time, quite a lot of workshops. I don’t really enjoy doing them to be honest. We started a thing called Handsworth Creative in 2014. This was me and another of my colleagues, a friend of mine who has subsequently died. Originally we started out as a community arts organization to try and get some public money to publish a comic. That never happened.

But Handsworth Creative has become a sort of umbrella organization in Handsworth for various sorts of arts and exhibition stuff. Where I said I was trying to get money to do a comic, what I wound up doing was workshops with schools and youth organizations. Drawing workshops. That ended up as an exhibition of prints of local Handsworth personalities, which toured around a little bit. Nothing to do with comics, whatsoever. (Laughs) That’s the way it worked. A lot of famous people come from Handsworth. Steve Winwood was born in Handsworth. And Charlie Chaplin was born in Handsworth, although it’s a controversial subject.

His son, Michael Chaplin believes entirely, and he has a connection with Handsworth. He comes over here from time to time. A friend of mine, Surjit Simplay, made a short film that was sort of based around the idea of Chaplin being born in Handsworth, in an oblique sort of way. The film was not a “documentary”, but very much a reverie playing with the idea of a gypsy boy and a local girl, both children, meeting on the Black Patch. In the film, the gypsy boy was played, as an old man, by Chaplin’s son Michael - and was shot in our kitchen! I was the producer of the film. Which means I was the man who had the big cigar and handed out the envelopes. (Laughs)

But the rest of Chaplin’s family, I don’t think that they accept that he was born here. But I’m convinced. I think there’s pretty good proof of it. He himself believed that he was born in the East of London for most of his life. When Michael was going through his father’s effects he unlocked a drawer in a desk and found a letter that was written to Charlie from a man around this area who said that Charlie was mistaken when he said he in his autobiography that he’d been born in the East End of London. But this guy knew better because he knew that he’d been born on the Black Patch. It was traditionally a place that the Romany people could camp and meet; it was at that time an industrial waste ground–which is presumably why the gypsies were allowed to use it–and is now a bit of park. Charlie’s mother was of that stock and was visiting when her baby was born, which was Charlie. She had probably immediately moved on and gone back to London, but this fellow who’d written the letter, it was his mother that was the midwife. So based on that evidence, Michael Chaplin, Charlie’s son, believes that he was born here in Handsworth and so we’ve taken that up as well. We’re claiming him.

I think it is much more common in England than in the States, how many places put a claim on people like that. Where they were born, where they taught, where they were buried, and every town has their claim to them and their celebrity. I think about Lewis Carroll in that.

Well, we’re a smaller place and we’ve been here longer.

Much longer. I remember a conversation with Bryan Talbot or Alan Moore - they were appearing at a convention in Boston and they were staying in a bed and breakfast that was claiming to 250 years old. And the house where the guest normally lived in England was over 400 years old. They joked, “Oh we’re going to stay in a modern hotel in Boston.” I have an American friend who is an electrician. He lived in England for several years. He talked about being gobsmacked doing work in a church right next to a 600-year old mural and stained glass window.

Yeah. I remember when Trina Robbins visited here, back in the early '70s and her going “Oh jeez, this house is so old.” And it was something like 1860. Not old at all.

Trina’s place is San Francisco is actually pretty old for California.

It’s one of the originals, isn’t it? Yes, I’ve been there. But not as old as what we have ‘round here. We’ve got what’s called a town hall; it’s sort of a records office, which is around the corner here, dated from 1168.

The church I was talking about, St. Mary’s church, the foundations of the tower are from the 11th century from 1000 and odd. They were originally the stones that were used in a Norman castle that was built in the park. Then they were used after that to build the church. The church itself has been there since about 1620. And I’m going to get a window in it.

Congratulations. That’s awesome.

Well there you go.

What are your top three favorite things that you’ve done so far?

Three things? Blimey. There was Intervention. Want to talk about Intervention?

Absolutely.

That was in the year 2000. Most of the time I don’t like to think of myself as an artist. I’m a cartoonist. But occasionally, now and again, I’ll do art. This was one of those times. There was a fellow, a house builder and a bit of a chancer. He realized that he could get money from the arts council and other places to set up an arts exhibition. The area I live in is subject to quite a lot of redevelopment. A lot of the older houses have been knocked down, because they’d fallen to pieces basically. But there were five houses in a street, Westminster Road, big houses, that were due for demolition but weren’t going to be knocked down for a few months. So he got hold of them. They were big old places, from about 1850. Three-story houses with basements as well. He got 50 artists together and we broke into the places and everybody took a room and sort of made it into an installation of some sort.

Dave, the guy who was running it, he took out an entire staircase and reinstalled it upside down. A friend of mine, Pauline, who lives across the road, and is a very good artist took the end of one of houses and knocked all three floors into one big space and then made a sort of installation that was based on slave ships, with huge pieces of timber brought in and enormous chains. Because one of things about this part of the world is that part of the industrial revolution here, one of the industries was metal work. They made slave chains and that sort of thing. So that firm, they still exist, she got them to contribute a lot of chains and money to this. Proper metal chains with links about 18 inches long, you know, draped around this wood in the end of this house. Very dark.

Somebody else filled a room with woven bamboo and willow.

I took an attic room and turned it into an observatory. Had a little skylight window so I put a telescope through that. I painted the entire room black, except that there were cartoon planets and spaceships and things around, and lots and lots of white stars dotted onto it. Then I put in a little platform with an Indian carpet on it and there was lighting, and the Blue Danube waltz playing. And it was like a little observatory. It became a very popular room because it was at the top of house, out of the way, and the local kids used to go up there and smoke weed. (Laughs)

So yeah we did this with this house. We went in there in November in 2000. It was absolutely freezing. We were up on the roof, trying to patch it. Jane took a room. She took photographs of the outside of the houses that were going to be pulled down. And colored them and mounted them and she had them in this room, but it just kept leaking the whole time, through the roof. We kept trying to patch it and it wouldn’t work. So in the end we just put a couple of rubber baths in it and collected all the rainwater. We had loads of plants in the room and her photographs. It was great.

What else was there? Oh yeah. Each of these houses had a garden. There were about 60 feet of garden behind each of these houses. And they were all joined together. When we first broke in [we] were sort of sweeping out broken glass and generally clearing out the rubbish and things. They started burning it out in the garden and cutting down some of the overgrowth. There was a local fella, a local Jamaican, a little old fella called Nelson. He comes poking round to see what was going on. He took it on himself to look after the fire. This fire just kept going. Always more and more stuff. Gradually we cleared all these gardens and cut the trees away and all of the rubbish out of the houses. Nelson was there for an entire month, looking after this fire. The fire grew to be of huge proportions. He had no idea what the hell was going on with art and all these weird people, doing weird things. But he just joined in with it and sat round by the fire and made sure that the fire never went out. We had to put night watchmen into the place and I took me turn at doing that. I was there overnight, I woke early and went out to garden at about half six and Nelson was already there by the fire. I said, “Aye, you’re out very early.” He says, “Ah yah mon, me wake up, me smell the fire going out, so me have to get out here.” (Laughs)

We did that for about a month. Then we closed it down. We had a big party, a band and things. By which time the five houses were absolutely transformed. We were all working on these rooms all the time. Very rarely was a room finished, it was continually evolving. It was a very strange thing. A very good experience, that was. The houses were eventually pulled down, years later actually.

Dave went on to do two or three more exhibitions of the same sort of thing. But I didn’t want to get involved with those because it took up too much time. I had to try and run my job as well. I was working late at night, then getting out in the day and working at Intervention. It was so much fun I didn’t want to do anything else.

What is the likelihood that you have a photo or two from that that you could forward me?

There weren’t really any photos. One of the things that wasn’t done with Intervention is that it wasn’t very well documented. In a way that was kind of the ethos of it. Get into the houses, do what you do and get out again. That was it. The fact that nothing was going to be permanent, nobody was going to make anything that was going to last longer than the exhibition.

Right. What else?

Spritely Records. Music.

I was just going to bring up Hunt Emerson and the Hound Dogs.

Unfortunately that’s something that I don’t do any more, either. I played music all me life. Since I was a kid. My first gig with a band was when I was 14. But I’ve never been somebody, certainly in later years, to sit down and practice on guitar. I only ever play if there’s an audience, even if it’s just one person. Consequently my guitar playing hasn’t improved since I was 16.

I was always a good singer. That’s what I did in the Hound Dogs. I played rhythm guitar and sang. The Hound Dogs was three people. There was Dermot Walker (aka Dog Walker), the guitarist, and Dawn Tibbetts (aka Rosie-Fingered Dawn Tibbetts) on bass, and Ron Collins (aka Rockin’ Ron) the drummer, and me (aka Hunt the c-c-c-cartoonist). The rest of them were a punk band called The Privates back in the day. They’ve always worked together. We just used to get together and play for fun in front rooms. We’d play at parties, if we had New Year's parties and things. We just went on for about 10 years. I don’t know if we were any good. But it was fun.

The thing was, you see, I was the singer and it was all blues and country music and covers, nothing original at all. The others were kind of serious musicians, including, in particular Ron. The last thing he wanted to be was the drummer in Hunt Emerson’s rock n’ roll band. (Laughs) So it was all a bit of bitty thing. Eventually we packed it in. The last gig we did was my 60th birthday, which we had on the grounds of a rugby social club. It nearly killed me. ‘Cause everybody was there and I shared it with another guy, a Sikh friend of mine. I ended up doing most of the work, driving a van around and putting up tents and all sorts of things. Then the band played, eventually. And then there was a fight. Jesse’s friends all got drunk and there was a fight. God it was madness. After that I swore I wasn’t going to have another birthday party. After that the band just didn’t get together again. It just sort of stopped. We didn’t argue or anything. It wasn’t musical differences or whatever, it just never happened again.

I sort of stopped playing the guitar as well. My guitar hasn’t been out of its case for about four years. I did pick up a guitar about six months ago, during me chemo, but me fingers wouldn’t work. So what I ought to do is get the guitar out and see if I can still play it or not. Unfortunately I think that’s all finished.

But then I had this other friend, Andrew, Andrew Cowen, who is a musical genius. He’s a journalist, or was a journalist, very good journalist, but he’s also a bit of genius at music production. He said to me one day “Would you fancy doing a record with me? I’ve always wanted to record a song called Josephine by John Otway. So we did it.

I played instruments and we got lots of other people in to play instruments. We had a wonderful afternoon doing a choir, backing vocals. Then Andrew commenced to make something like forty mixes of the track, all of them very different to each other. Eventually we put it out as a CD, with about half a dozen mixes on it. We did a couple hundred of them and they sold quite well, eventually. So we did another one quite quickly. We really shouldn’t have, it was too soon. Got overexcited and put out quite lot of them and that didn’t sell at all. (Laughs).

And we did a few other things. We did a couple of compilation albums with friends, other musicians around and another couple of records, and then Andrew went and died in 2016. He got multiple cancers and passed away. So that was the end of that. All of the recordings disappeared. He had them on his computer, but nobody could find them. So you can hear them. They are around on the internet a bit but they’ve disappeared now, they’ve gone. That was that.

Any thing that you wish you could do over? Any work where you think “I would do that so differently now”?

Mostly if I do work and I put it away for a couple of months then I look at it, I hate it. But if I’m looking at older work now I think, “That’s all right. That went well.” Something like Casanova is really well-drawn. I thought it was quite well-written as well. It’s a shame it didn’t sell very much.

In terms of life I’d like to re-do most of my teenage years and my early 20s, as well. I’d like to do those again, and get it right this time. I’d like to do Art College again and get it right, ‘cause I blew it the first time round.

But as for the work, I don’t know. I work quite fast, but actually drawing is quite a slow process, it takes a while to do, I churn out a lot of work and I don’t tend to go back much.

Anybody’s work you are following these days?

I don’t really know who’s doing what. John McCrea’s work I know. But that’s because he lives round the corner. That’s somebody you should interview. Do you know his work?

I know the name, but not that much about his work.

He's very well known in the mainstream. He did a character called Hitman.

Right.

With-- oh god, what’s the writer’s name? An old school friend of his from Ireland.

Garth Ennis?

Yes. Anyway, John’s good. I don’t have a lot of contacts with comics, other than Facebook. I teach a lot of young cartoonists, and I’m still in touch with a lot of them. MC Squared that was. Midland Comics Collective. Workshops again. You have to keep doing bloody workshops all the time. But they’ve got on, doing their own things.

I think that’s the difference. When I started there wasn’t anything like that ‘cause comics wasn’t a career. There was no education. I was actively discouraged from drawing cartoons when I did me bit at art college. It wasn’t seen as being any way serious what-so-ever. Comics were just looked down on. But now days comics are seen as the ninth art, which means it has all of the structure around it, including degree courses in universities and workshops everywhere you look. I don’t know. Is that a good thing? I’m not sure. I mean there was a lot of very original work came out in the early days. From people who were just making it up as they went along, basically. It’s no good getting me talking about comics theory, because I know nothing about it.

As you were saying, when you started you just did the work, found what you found, liked what you liked. Now there is the possibility of having theory and classes. That was never part of your original purview.

Doing sort of “way back” things, I wanted to touch on the ska retrospective in Coventry. I loved your quote about the posters being done on such flimsy paper you were surprised they lasted the night, very well 40 years.

Yes, well that was a fun part of life. I went down to Coventry to see the exhibition. It was good fun. Interesting. Nobody has ever contacted me about it. I was a little surprised-- well, not surprised, I knew that I ought to be in there because I was part of that scene. But I didn’t know I was going to be in it and I’ve got a couple of copies of that poster and the other ones that were in that exhibition and my copies are in much better nick than those ones. (Laughs)

Don’t tell anybody, they’ll want them.

Well if they’d asked me, see… I got involved when the band The Beat first started. A couple of friends of mine were sort of managing a reggae band in Handsworth. And The Beat came along and said “Could you do something for us?” So I did. It all took off very quickly because there was suddenly this Two-Tone explosion going on. And The Beat needed a visual image and graphics and things and I was the only person in their immediate circle who knew anything about that. So I got roped in to do it. When I started they didn’t really know what they wanted, except that they didn’t want any cartoons. So I had to kind of invent a new way of drawing to work with them. Which is what I’ve done with them ever since.

The Beat Girl has become very iconic. I don’t have copyright on this stuff. That was something that was made plain from the start. They’d pay me fees, but they were keeping copyright. And right enough as well. Imagine the nightmare of trying to follow up royalty payments for stuff that’s got those graphics on it. It gets used everywhere. I just did a commission over the holiday for somebody in the States, a woman wanted a drawing of the Beat Girl. So I did her a nice drawing of the Beat Girl. She’s going to have it tattooed as well.

And The Beat was very exciting for a couple of years. And then it all fell apart in acrimony, as these things do. But then over time they’ve made up their differences, more or less. It’s never going to reform, because half of them have died now. Ranking Roger ran a version of The Beat for all these years. And his was the best version to be honest. It was a wonderful live band, absolutely fantastic! Everett [Morton] the drummer, he was in it for a while, then he split and made his own version of the band. And Everett died this last year. And Saxa [Lionel Martin], the old guy who played the saxophone, he died six or seven years ago. Which is a shame. They’re all going.

But Dave Wakeling still runs The English Beat in Los Angeles. I got to do his album just before the pandemic, 2018. I was over there. He invited me over, ‘cause his band was headlining a charity gig that this guy puts on his back garden every year. So they got me involved to come over and do a drawing that was going to be raffled off and do drawings while I was there, and to talk to Dave about doing the album sleeve. So Jane and I got a free holiday in L.A. Then he did this album called Here We Go Love! I did all the artwork for that - the singles and things. It’s a brilliant album. So he’s still running The Beat over there. And Everett’s band is talking about keeping going, although there are no original Beat members in it now. Any more?

I was thinking about The Specials, and all their various permutations. I did a lot of work with a version of them in the late '90s.

You did?

They had a new album out, Guilty ‘til Proved Innocent! They were touring and at the time I was doing a lot of music writing, so I did lots of local reviews and interviews with both Neville [Staples] and Lynval [Golding]. It was a lot of fun.

They were a great band in the day. I haven’t kept up with them. I haven’t heard their new incarnation at all. But one of the best gigs of my life was The Beat and The Specials in Coventry on New Year’s Eve one year.

Ohhhh.

That was something. With Neville climbing up the proscenium arch. Wow that was amazing.

He was still doing that in the '90s.

This is another “way back” sort of question. In the previous Journal interview you talked about wanting to draw comics that were underground, but not focused on sex and drugs because you wanted to be able to show your mum. Did she ever see Firkin or Lady Chatterley’s Lover? If so, how did she and your dad react?

Well, my dad’s been dead a long time, since 1992. He saw Lady Chatterley and called it filth. Told my mother to throw it out. But she didn’t, she kept it. Me dad really didn’t have any time for or understanding of what I was doing at all. My mum also doesn’t understand it, but she did appreciate that I’ve got talent and she’s proud of the fact that I’m doing books and things. She’s 93 now. She lives in a nice home and my brother and sister-in-law look after her a lot. She’s ok.

But I don’t know if she ever read any of the books, but she certainly had them, I’d send them to her.

It turns out she kept all sorts of things. Me brother was sorting through some of the stuff and he found a couple of old drawings things that I’d done when I was at art college in 1967 or ’68. And these were just exercises. Not something you’d keep at all. And she’d kept them.

I think there are things that are sentimental to a parent in a way that is very different from how you approach them as an artist.

I left home quite early. I left home at 19 and I went on me own path for about five years. Had very little contact with home at all. It’s been kind of like that since. I mean I’m very close to me mum, but she doesn’t know who I am or what I do. (Laughs) She knows who I am, but you know what I mean.

I do. I think that dynamic is one a lot of artists can relate to.

There are a couple of writers, Tym Manley and Kevin Jackson we’ve talked about a little bit.

Tym Manley. When I was first offered Firkin I said “Yeah, I’ll do this, but I don’t want to anything like Little Annie Fanny in Playboy, or Wicked Wanda in Penthouse. I don’t want to do anything like that.” They said “No, we want you to do what you do, an underground comic.” I said, “Well, I can’t write these.” So they gave me a writer and that was Tym. He’d never written comics before, but he’s been involved with the magazine [Fiesta] for a long time. So that’s how we first got to work together. We worked for nearly 40 years and I met him about six times in all of that time. We’d occasionally chat on the phone, but basically he’d send me the script and I’d get on and do them. Or I’d re-write them usually. I know how to do comics. He would come up with the ideas and I knew how to turn them into comics. Sometimes I’d write them entirely myself. Sometimes I’d take [a] germ of an idea of his. Sometimes they didn’t need changing. I was very free to do what I wanted with them and make them work.

Who else? Ian Billings is somebody I’ve been working with over the last few years. He’s a guy who writes pantomimes. You probably don’t know what pantomime is. It’s a very English form of theater, which is put on at Christmas. It’s for children, but grown ups are involved as well. It’s very traditional and it’s very corny and you get TV stars in it and sports people sometimes. It’s full of dreadful jokes and slapstick comedy and all based on traditional fairy stories. Ian used to write and direct these. Still does from time to time. He’s a children’s comedian - a stand-up comedian for children. He also writes kids’ books and works on children’s workshops and things.

For several years now he’s got me involved in doing workshops with the schools around the area. Doing things like taking groups of kids around the ancient Egyptian section of the museum and doing drawings with them, based on what’s there, and then talking about what’s there. That went on for some weeks. They were also looking at traditional Inca and Aztec pottery. The workshops went on from that to do designs for teepees. I found myself, in the middle of summer, painting teepees outside of a junior school somewhere in Tipton. I’m wondering, “What the hell am I doing here? What is all of this.”

These things would sort of start one way and wander on through to the most unexpected conclusions. One of the things we did together-- we’d go into a school and with a class and he would workshop with them on character and story, and then I would go in the following day and workshop with them on drawing the characters. Then he would go away and write a story based on what the kids had done and I would do a couple of big pictures illustrating it. Then, eventually we’d done eight schools or something, the book would be printed and published as a private edition for the schools only, with the kids’ stories and my drawings and some of the kids’ drawings as well. We did that in quite a few places, several years running.

And I’ve just finished drawing a book for children. An actual kids’ book called Moby Duck that Ian’s written. This is not with workshops, this is just us doing it. He has a publisher who does kids’ books and they’re going to do that sometime in spring 2022. The first kids’ book I’ve ever done. I’ve always avoided doing kids’ books. The Beano is different, that’s a comic. But doing an actual book. And now he’s saying, “What are we doing next? What are we doing next?” I’m saying, “Well, we’re going to see how this sells before we do anything else.”

I think that kids would respond really well your style. It’s very engaging. Your subject matter has not historically been oriented to kids…

That’s right. Nor the style of drawing. I think that as cartoons in general have developed, my style of drawing has become acceptable to children now, certain aspects of it any way.

I think the caricature elements of it would appeal; kids respond to terrible noses and wild hair and those kinds of things.

Oh they love all of that, they do.

You have done a really amazing job of drawing the experience of creating or listening to music or being in a musical environment. I was wondering about your approach to that and if you listen to music while you draw?

No, I don’t. If I’m writing I have to have silence. If I’m drawing I find music to be very distracting. I like to have a voice nattering away. So I listen to the BBC. More recently I listen to a few podcasts. BBC does it for me. Radio 4 is their main kind of spoken word outlet. More recently they have Radio 4 Extra. They are making use of their archives. So they play a lot of old comedies, stuff from the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s. They also play drama, and all sorts of old documentaries turn up. I listen to that all of the time.

I don’t listen to music much at all. I find these days if I want to hear something-- if I want to hear, sa,y Albert King, I just go onto YouTube, and after five tracks I’ve had enough. (Laughs) So I turn it off. It’s all old stuff, I’m afraid. I can’t abide hip hop and what they call r&b these days. I just don’t get on with it. I like Bob Dylan, The Beatles. I like country music. I like Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash. I like folk music. But I’m not fanatic for any kind of music. Sorry.

There is nothing to apologize for. You like what you like. I have talked to so many people who are artists as well as musicians, they often have special relationship with drawing music.

I can see what you mean about drawing the music. I’m aware of that. I’m not sure why it is I can do this. But it’s like, what is the cartoon for? And for me it’s about expressing some sort of feeling or emotion in whatever way. Usually that feeling or emotion is something like ridiculousness. It’s not a big heavy thing. So often it’s finding a way of making characters emote, drawing music around them can help do that.

You seemed to want to avoid politics in the '90s. But you’ve worked with community organizations and libraries to do comics spotlighting many issues, including children’s rights, homelessness, drug abuse, safe sex and the importance of bedtime stories. This seems like politics at its best and most practical. Do you still see yourself as eschewing politics?

Yes and no. I’m more aware of politics. I used to ignore it as much as I could because all I could do with it is get angry. It’s the same now. I’m not a political cartoonist. I don’t know how to turn what I do into a sort of comment on it. However, what you said about the fact that I do this community work and things being politics made me think. That’s very true. I hadn’t thought of it that way. So I suppose in a way I do have a political side to what I do, which has to do with getting involved with my local area and making me work do something or other around the place. Trying for it to be more than just ephemera. Otherwise that’s all it is.

I think community-based work is the most effective and practical politics.

I’m very interested in history, and in particular local history. Quite a lot of what I’ve done around here has been about the history of the place. And thinking about it, that is probably political in itself. In that if what I am doing is aimed at, say, local school children, and it’s something about their area and about the history of the place, then that has got to, hopefully, give them a different view of their world and of their neighborhood and hopefully give it a positive view. ‘Cause I do try to make things positive.

Do you care to comment on Brexit and all of the nationalism in the world today?

Don’t get me started. Don’t get me started. (Laughs) I am more aware of things these days because over the last two or three years we’ve had a subscription to the Guardian. Which is a left-wing newspaper. Now in fact this week is the last week of the subscription. There was just too many newspapers coming into the house, and they weren’t all getting read. But it does mean that I’ve been reading more and keeping up more with what’s going on in the world. And it’s just horrifying, isn’t it? Trump. Brexit. What’s going on in Poland and Brazil. It’s just awful. And there is nothing I can do about it, at all.

I have a friend, she’s engaged about the whole trans thing. And it makes her so angry and bitter the whole time. I think it spoils her life and I don’t want to be like that. I don’t want to be involved so much in something that I can have no influence on whatsoever. I’m very aware of it. If voting is the only thing I can do, well then I’ll vote. Give me something else that I can do and I will do it. But I can’t spend me life being churned up by all this stuff, the whole time. Not in the way that my friend is. She goes on demos and things like this. Not for me. I’m not a demo person. I never have been.

I can understand that. So what would you like to talk about that I haven’t asked about?

Let me think, what else is there?

We didn’t actually discuss any of your awards.

I’ve had a few awards, one or two. I did a lot of traveling in the '90s in particular. I did a lot of comic festivals around Europe. Finland. I was in Finland about 12 times, I think. I like that place. So I’d be invited as a guest, but I don’t think I won many awards there.

I’ve got the Sergio, which I’m very proud of. That was named after Sergio Aragonés, possibly our greatest living cartoonist, greatest living comics artist, he’s got to be. He’s a wonderful man. Have you met him at all?

I have met him at conventions a few times.

Isn’t he just great?

He is. Sergio is friends with a friend, Phil Yeh. Phil and I used to live in the same town, and I briefly met Sergio at Phil’s house once.

I met Phil Yeh once, in Finland as it happens. (Both laugh) He was over there at one of the festivals.

There was a comics festival in a town called Kemi, way up in the north of Finland. They have an icebreaker, a ship. It’s on the Gulf of Bothnia and they have to keep the gulf clear, keep the seaways clear. So the town owns this icebreaker, which they run as sort of a tourist attraction. It’s got a restaurant and a bar on it - as well as breaking ice, people go onboard and they have receptions and that sort of thing. I went on that when I was up there. We sailed out onto the Gulf of Bothnia, breaking ice. When we came to a halt there was about five foot of green sea ice that was broken by the front of the ship. Then it was the sea underneath. So I got to put on a rubber suit and I got to go and float and bob around in the frozen sea, underneath this icebreaker. They also have a cherry picker crane on the bow of the boat. You get to sit in the crane and it lowers itself over the bow. So that while the thing is going through the ice you get to hang down in front of the ship. That’s another occasion when I thought to myself, “I never imagined that I would find myself here.” (Laughs)

I’ve done some weird things. Robert Crumb was at one [festival] once, when I was there. He and I got hold of a guitar and a banjo and there were a couple of Finnish guys who came along–they brought all the instruments–and we played together in the bar for about three or four hours, just improvising and jamming and playing country stuff. Which was good fun. He’s an interesting guy. I’ve met him a few times, but he never remembers me.

Gilbert Shelton is another matter. I really love Gilbert. Gilbert along with Sergio are probably my favorite comics artists. Gilbert has been a good friend. I lived in Paris in 1989 for six months. I stayed there for seven weeks another time. Spent lots of time with Gilbert then, just walking around Paris, sightseeing, flaneuring. Being a flaneur.

I can’t think of anything else. I think we’ve covered everything.

When I pitched this interview with you, my take was that the world is not an equitable place because your name should be mentioned when people are talking about the underground greats. It doesn’t seem to happen in the States very often. I think part of that might be distribution issues here.

That’s very nice of you to say that. Because I don’t know why I should be classed with those people. I don’t consider myself in the same class. I know that I’m good, but I don’t think of myself as particularly special. I do have recognition. A lot of people here know me, as much from Fiesta and Firkin as anything actually. I continually find gentlemen of a certain age saying “I first came across your work in me Dad’s top drawer, in Fiesta magazine.”

But I’ve never understood why I do seem to have this reputation. I like it. It’s nice. I’m very pleased that my work has been successful as it has been. Which isn’t very successful, but as comics sometimes they work well. I’ve never felt myself to be in the top rank. I’m too far out, too far away from it all to be that.

I don’t think you have to be in the mix in that way to count. And it may sound strange, but I find gentleness in your work that I often don’t see in Crumb or even Gilbert’s work. You have that great underground style, that underground sensibility, certainly lots of fun with sex, but it has never felt angry or abusive.

Gentleness. That’s nice of you to say so. Good. I hope that is the case. Because actually that is something that I do try to keep going. I’m not a great fan of violence in comics. It’s there. It’s something that you draw for comic effect and things. My friend John McCrea, he does some great drawings, some wonderful sketches and drawings. People love his work and he’s always selling commissions. But they’re always of people having their teeth pushed out and being shot. I don’t know why it is that people go for these kinds of images. I’m not really interested in all that. I like things to be, as you say, gentle and funny. That’s what it’s about. You’ve made me really happy saying that. Thank you very much. You’ve made my night.

Well, that is a wonderful note to end on. I’ve kept you for far too long. Thank you so much.

Thanks to you as well. Have a good new year.