In one of my favorite poems, “Poem”, by Elizabeth Bishop, Bishop describes a painting, a family heirloom painted by her uncle and passed down from generation to generation. The poem is ekphrastic, meaning it is a poem about a painting, although for the sake of this article I’m going to be using the term more generally, as an antithetical act of translation. As Bishop describes the painting, she begins to realize she recognizes the place her uncle has painted, and the poem chronicles a dawning catharsis as Bishop, and the reader along with her, sees the painting in a new way, and as if for the first time. Since the place in the painting is an actual place where Bishop and the uncle have lived at different points in time, the poem turns into a meditation on art and life.

Speaking of her uncle, Bishop writes in the final stanza,

Our visions coincided–“visions” is

too serious a word–our looks, two looks:

art “copying from life” and life itself,

life and the memory of it so compressed

they’ve turned into each other. Which is which?

Life and the memory of it cramped,

dim, on a piece of Bristol board,

dim, but how live, how touching in detail

–the little that we get for free,

the little of our earthly trust. Not much.

About the size of our abidance

along with theirs: the munching cows,

the iris, crisp and shivering, the water

still standing from spring freshets,

the yet-to-be-dismantled elms, the geese.

It’s as if we are looking at the famous optical illusion of the rabbit and the duck. One one side is life, the memories and experiences associated with the landscape; and on the other side, art, the painting itself, and the poem about the painting. On one side is life, the memories and experiences associated with the landscape; and on the other side, art, the painting itself. There is an ekphrastic process happening, not just in the sense of words about images, but in the sense of life and art. What is being described? A series of iterations: an uncle painting the landscape around him; a niece looking at the painting of the place; the same niece writing a poem about the painting of the place; and the reader reading the poem by the niece. To use Elaine Scarry’s terms, one mode, perceptual reality, is translated into another mode, the sensuous content of a painting, which is then translated into a third mode, the mimetic content of a poem. And of course, these various contents and modes are not objective features of perceptual reality, but specific slants on it by three artists - the uncle, Bishop, and the reader. What does this tell us about art and life?

Two important books of scholarship on differences between art and life–Michael Clune’s Writing Against Time and Scarry’s Dreaming by the Book–attempt, in different ways, to think about Bishop’s question, “Which is which?” For Scarry, art is an attempt to recreate the vividness of the perceptual world through language, which she argues is an astonishing feat, considering the grayness and two-dimensionality of our customary imaginings when not under the tutelage of a great author. For Clune, art is more vivid than the perceptual world, which can fade because of habit; art transforms our perception of the perceptual world by intensifying it. Scarry emphasizes the experience of the reader inside a book; Clune emphasizes the experience of a reader outside the book and in the world. Scarry places more weight on the vividness of the world; Clune places more weight on the vividness of the artwork.

Both Scarry and Clune are united by a fascination with the how of seeing more than the what. Yet despite their original chronicles of the image-making processes, neither looks very much at works of literature that involve, to use Scarry’s terms, sensuous content, but rather at works of mimetic content. Both are endlessly moved by the manner in which mimetic content represents sensuous content–Clune writes about music in Proust, for example, or Scarry describes how a Wordsworth poem hints at the mechanisms of perception through a painterly description–but their emphases are weighted in mimetic content. (Scarry does write some fascinating things about cartoons, and Clune has written two memoirs; both are in a large sense artists-as-critics, but one feels at times that the nature of academia dissuades against fruitful syncretisms.) The subject being discussed in those two books–the sensation of perception, the experience of image making–is biased towards language, and therefore towards certain genres of literature, poetry and prose, over other genres, like graphic novels, comics and cartoons, which contain mimetic content, sensuous content, and narration.

I am not an academic, and do not know well the academic landscape. But it seems unfortunate that there is not much work being done, or attention being given, to literary comics and cartoons by artists like Julie Doucet, Gabrielle Bell, Ben Katchor and Liana Finck, that seem to me to be as strong as anything being created today in poetry or prose. Unlike poetry and prose, their work combines image, voice, and narration. And their work evinces an intense awareness of both the literary and artistic traditions, while making them their own. For that reason, like the works of William Blake, Franz Kafka or John Ashbery, they introduce a quality of uncategorizability that throws a wrench not only into the act of categorization, but interpretation, of thinking, while emphasizing feeling.

I am not an academic, and do not know well the academic landscape. But it seems unfortunate that there is not much work being done, or attention being given, to literary comics and cartoons by artists like Julie Doucet, Gabrielle Bell, Ben Katchor and Liana Finck, that seem to me to be as strong as anything being created today in poetry or prose. Unlike poetry and prose, their work combines image, voice, and narration. And their work evinces an intense awareness of both the literary and artistic traditions, while making them their own. For that reason, like the works of William Blake, Franz Kafka or John Ashbery, they introduce a quality of uncategorizability that throws a wrench not only into the act of categorization, but interpretation, of thinking, while emphasizing feeling.

The strongest works in comics and cartoons suggests the endlessness and the limits of interpretation, both of which seem to pivot around issues related to silence. It is not surprising, therefore, that all four artists mentioned above possess an interest in religion, whether overtly or covertly. Images, unlike poems, short stories, plays and novels, are works of art that contain a deep silence within themselves. Language can arise from silence, and gesture towards it–think of the poems of Paul Celan, or Wallace Stevens–but images, unlike poetry, do not speak. They are a form of language, but they are not language. For this reason, both literature and art, paradoxically enough, might be best captured through audible metaphors, but the former emphasizes the heard coming out from the unheard, and the latter the unheard coming from the heard.

Because cartoons and comics contain such a weight in the sensuous, they also suggest an aspect of embodiment that is not a characteristic feature of mimetic content. A painting, a sculpture, a photograph, a film, a poem and a novel are all performances, whether synchronic or diachronic, but the first four are more the products of different bodily expressions, of hand applying paint, of chiseling stone, of moving in the world to find an angle that hasn’t been seen, with one’s camera to pull out the most dramatic potential possible; whereas the latter two are the product of the body in less strenuous acts of motion. The image in a comic or cartoon produces sensuous content, suggestive of embodiment, even while our acts of reading it mimics the ways in which we encounter mimetic content, and therefore raises questions about different gradients of perception and performance. What is the difference between reading and viewing? Between, in Bishop’s terms, vision and looking? What is the difference between the rhythm of prose and the rhythm of dance? Between watching a film and reading a graphic novel? Between embodiment in the world and embodiment in a text?

Because cartoons and comics contain such a weight in the sensuous, they also suggest an aspect of embodiment that is not a characteristic feature of mimetic content. A painting, a sculpture, a photograph, a film, a poem and a novel are all performances, whether synchronic or diachronic, but the first four are more the products of different bodily expressions, of hand applying paint, of chiseling stone, of moving in the world to find an angle that hasn’t been seen, with one’s camera to pull out the most dramatic potential possible; whereas the latter two are the product of the body in less strenuous acts of motion. The image in a comic or cartoon produces sensuous content, suggestive of embodiment, even while our acts of reading it mimics the ways in which we encounter mimetic content, and therefore raises questions about different gradients of perception and performance. What is the difference between reading and viewing? Between, in Bishop’s terms, vision and looking? What is the difference between the rhythm of prose and the rhythm of dance? Between watching a film and reading a graphic novel? Between embodiment in the world and embodiment in a text?

These are phenomenological questions. And I think they get at something important about distinctions. Often the finest of lines demarcates traditions, and these lines shift historically to accommodate changes in the arts. All distinctions are inherently ekphrastic. Why? Because all distinctions are inherently antithetical - there is no way to say one thing (private) without in some sense saying the opposite thing (public), and therefore everything we see and hear is a translation from something else. The etymology of tradition means both a delivery and a betrayal. Reality is “and” and “or,” while also “is”; if we remark on the generous use of black in a painting, we are simultaneously calling attention to the absence of white; if we speak of a mother, we are simultaneously speaking of a father; if we speak of art, we are simultaneously speaking of life. Nothing exists in isolation–something that the internet seems to foreground, with its infinite trail of links connecting the most disparate things imaginable–and this perhaps explains why there has been such an interest lately in the ethics of interdisciplinarity. It’s a matter of ratios, and the amount of priority we give to these ratios, and why. But if everything means everything else, how do we preserve distinctions that matter?

Perhaps it is this very question that explains why we have been so obsessed contemporaneously with identity and differences between aesthetics and ethics. If everything is connected, if we are all part of a kind of never-ending cosmic fabric connected by unimaginable amount of threads in every direction, where is there room for individuality, for saying “sorry, that’s you, and this is me, that’s your tradition, this is mine”? How does history fit into the picture, or culture, or biography? In the 21st century, following the Shoah and the cataclysm of two world wars, in an age of climate change and COVID, and the perennial issues of racism and sexism, homophobia and antisemitism and discrimination against people with mental illnesses, or for that matter differences in any guise, what role do the arts play? What role can they play? Where are we, where have we come from, and where are we going?

These are not just academic questions. The frames we use to think about things shape those things. And because graphic novels are a relatively new phenomenon compared to poetry and prose, we need to think carefully about the lenses we apply to them, especially considering the strength of work in that genre by the artists mentioned above.

This pollination between the arts–this contemporary ekphrasis–is ancient, is in a sense the foundation of why we create art, which is always a form of translation, but it seems to be applied only by narrower definitions of literature, as evidenced by the absence of studies exploring the relationship between literary comics like Bell’s, Finck’s, Chris Ware’s and Katchor’s, and the literary tradition. An ekphrastic tendency, which we already find in the works of Emerson, Whitman and Dickinson, finds new expression in these artists’ work, all of which trouble our distinctions between image and word, mimetic and sensuous, motion and motionlessness.

* * *

To illustrate my point, I want to provide a short overview of the work of British-American cartoonist Gabrielle Bell, who I think is one of the strongest artists working today in what we might just as well call literary comics, and who does not receive nearly as much attention as she deserves. Original artists often escape our radars, for lots of reasons, but often it is because we are not trained to discern newness. Bell’s work is new because of its combination of the distinctiveness of her voice and her uncanny ability to represent body language in the cartoon short story and semi-autobiographical diary comic. In other words, she combines the best of both literary and visual traditions, both mimetic and sensuous content paced within the rhythm of a narrative. Through the literary tradition, Bell creates a fictional Gabrielle Bell who holds divergent contraries in a natural manner;1 through the literary and visual traditions, Bell represents inexhaustible polysemies of meaning; and through the visual tradition, Bell communicates a silent disjunctive timelessness that honors the best of (primarily) aesthetic, visual, and (secondarily) religious traditions while subverting all three in fascinating ways.

A good example of Bell’s early work is in Lucky, her second book. A fictional Bell as a child walks into her mother’s bedroom, where she is reading a book:

This is a brilliant representation of the most ekphrastic of moments, which we read in what feels like seconds. The title, “Mom”, lends itself to the same potent anonymity as the title “Poem” by Bishop. It is all about translations: an author’s voice to the mother’s voice, the mother’s voice to the fictional Bell’s ears, the memory of an experience to the visual and verbal, the visual to the panels, the panels to the gestalt of the page, the fictional Bell’s experience to our experience, the fictional Bell’s experience to her pet rabbit; mother to daughter; art to life and back again. Like the work of Doucet, whom Bell has cited as her main influence, the work is feminist, idiosyncratic, and universal. And the effect as a whole produces an intense polysemy. How do we read the second panel on the second page? Is it humorous, seeing the incongruity between the child casually holding the drooping pet rabbit while her mom launches into a somber Paterian encomium to the fragrance of embalmed love? Poignant? Something different? In Lucky, as in all of Bell’s work, we are always being thrown upon ourselves and forced to question how we see. Her work, like the best art in the literary and visual traditions, always interprets us more than we can interpret it.

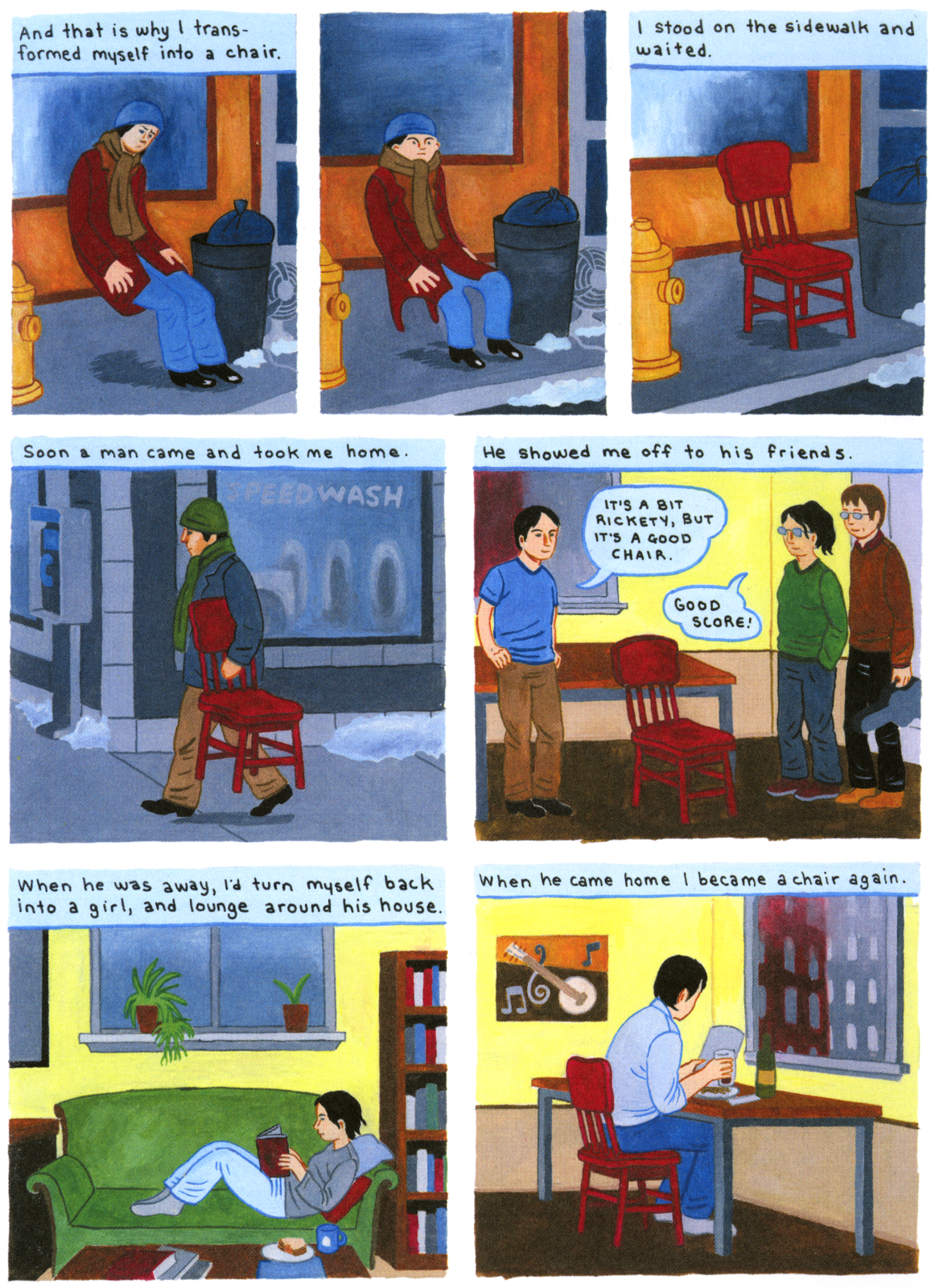

Bell’s third book, Cecil and Jordan in New York, provides another strong example of these dynamics, troubling our distinctions and assumptions about what literature and art can or should mean or be. In the opening eponymous story, turned into a short film, “Interior Design”, in collaboration with the filmmaker Michel Gondry, we are greeted with Bell’s characteristic hopefulness, whimsy, and muted despair. A young unnamed woman narrating the story has just moved to New York with her boyfriend, and they are both staying at their friends’ house while attempting to locate work and housing. There is a blizzard; we hear about the boyfriend’s depressing job working 13 hours at a store; the couple goes to a work party where the narrator, because of the endlessly bizarre context of work parties, seems forced in demeaning ways to define herself exclusively in relationship to her boyfriend. The despair, very muted, seeps strangely into the light color of the panels. We see the young woman walking across the street in the snow without proper footwear. The captions reads, “But it wasn’t like I had anywhere to go.” The next page reads:

This is another great example of translation, in this case between literary modes, which explains partly why and how the scene is so painful, lonely, quiet and humorous at the same time. It seems these ways in part because the quietness of the mode of literary realism continues during the scene in which the narrator turns herself into a chair, so the incongruity between the fantastically depressing event–a girl turning herself into a chair–and the way in which it is represented immediately strikes us as ridiculous and heartbreaking. What makes the moment masterful is that the very mutedness of the scene, owing to its embeddedness in a mode of literary realism, is the perfect vehicle for conveying the narrator’s enormous sense of bewilderment, of a gap between relentlessly jarring emotional experiences and the staidness of a literary realism that cannot accommodate these experiences. This suggests a failure of translation, a kind of ekphrastic impasse, a discordance between within and without that must find expression in an act of contortion in order to find expression.

We are focusing on literary modes, but the power of the work resides in the details, by which I mean the combination of the writing, drawings and narration. For example, in the page that follows, which is also the last page of the story, we read:

“I wondered how Jordan was doing. I wondered how the car was. I decided I wouldn’t be missed much. But the days slip by so pleasantly that such thoughts don’t linger long in my mind. Sometimes, there are close calls. But then, I’ve never felt so useful.” How do we read these sentences? One feels like a suicide note, “I decided I wouldn’t be missed much”; others like a note from the already dead, “I wondered how Jordan was doing. I wondered how the car was”; and one like a potent combination of anger, irony, and outrage, masked behind a parodic tone of how a cliched woman in a mode of literary realism might sound: “But the days slip by so pleasantly that such thoughts don’t linger long in my mind.” Yet it is also disturbingly humorous, as in the panel where a roommate walks into the chair taking a bath. Then the last caption reads, “But then, I’ve never felt so useful.” These lines evince a mastery of tone, in writing, drawing and pacing. Synchronic and diachronic, sensuous and mimetic, it’s a moving act of ekphrasis, and an example of some of the best work in literature and art out there.

Because of Bell’s mastery of tone in art and literature, there is a quality of her work that, while hoping not to reduce it to lexical modes of literature, feels closer to poetry and its interest in voice and states of mind and feeling. Perhaps this is because of the relationship between Bell’s work and silence. Images do not speak, and there is an inextricable relationship between silence and both religion and trauma, which are major preoccupations of Bell’s work.2 There is a presence to Bell’s work, especially including her most recent work on Patreon. One parallel would be the effect of the last line of a haiku, the way in which we experience a kind of force, a moment of satori, a gust of consciousness, a confidently shy revelation. Her work manages to be polysemous and numinous, suggesting the endlessness and the limits of interpretation - the heard out of the unheard, the unheard out of the heard. A good example is her adaptation, unsurprisingly, of a poem by the Russian poet Sasha Chernyi, which can be found on her blog.

Bell’s work is unique, but it is also a part of an ongoing conversation about ekphrasis in the context of genre, art form, mimesis, sensuousness, fiction, autobiography, art, life, embodiment and performance. Writers and artists like May Swenson, Jay Wright, Thylias Moss, Anne Carson, Ben Lerner, John Beer, Ariana Reines and Liana Finck also produce works of heretical hyphenation, unstitching literary and artistic traditions to stitch them in new ways. They are enormously contemporary and enormously ekphrastic at the same time, while harking back to the power of ancient sources like Horace. Bell’s work in semi-autobiographical diary comics is equal to the work of these artists, but she has received the least attention. She is an authentic descendant, like the artists mentioned above, of an ekphrastic tradition that includes Blake and Bishop; a tradition of literary cartoonists that includes George Herriman, R. Crumb, Art Spiegelman and Julie Doucet; and a tradition of prose exploring fiction and autobiography that includes Philip Roth, Chris Kraus, Sheila Heti and Joshua Cohen. Her omission in the literary universe, therefore, is unfortunate, considering her achievement, and the importance of what this means for thinking about art and life.

* * *

- Some of the many contraries we find in Bell’s work are a severe logic combined with a rich and intense feeling world; a whimsy combined with a despair; a wildness combined with an urbaneness; a shyness combined with the ability to shatter taboos; a rawness combined with a lyricism; and a child-like quality combined with a maturity for addressing the subtleties of interpersonal relationships. Do we ascribe this to the fictional Bell, the author Bell, or some strange combination of both?

- Trauma in Bell's work is discussed in Sarah Hildebrand's "Ghost Cats and the Specter of the Self: Telling Trauma in the Works of Gabrielle Bell", which can be found in The Comics of Julie Doucet and Gabrielle Bell: A Place inside Yourself (Tahneer Oksman & Seamus O'Malley eds.; University Press of Mississippi, 2019). Hildebrand makes some important inroads for discussing the role that trauma plays in Bell's work, but sometimes she emphasizes trauma and confessionalism too much, while arguing that Bell's work succeeds by not being confessional. This makes her approach confusing. For example, she writes: "Even in the therapeutic space, nothing is exposed of Bell that readers don't already know" (83). Tonally, this sentence suggests disappointment, and therefore a critique of Bell's work. But the critique says more about Hildebrand's hopes for the work than what I perceive Bell to be actually doing. Similarly, Hildebrand praises Bell for avoiding melodrama, which she (Bell) actually does, yet Hildebrand writes, "[the most poignant chapter]...provides a long-awaited dive into Bell's past." The language "a long-awaited dive" is sensationalist. This is why, when Hildebrand contextualizes Bell's work in the context of Leslie Jamison's "post-wounded woman"– women who stay clever or numb rather than being more honest about their feelings–one wonders who exactly Hildebrand is describing, for there is an enormous warmth and authenticity to Bell's work, and cleverness and numbness seem completely remote from Bell's entire body of work and the animating spirit it represents. Because Hildebrand assumes that confessionalism equals authenticity, despite the argument in her article about Bell's work succeeding because it is not confessional, she limits her frame to specific traumatic episodes in Bell's work. But trauma surfaces everywhere in Bell's work, all the time, in overt and covert ways. For that reason, Hildebrand is too literal - she minimizes trauma while attempting to do the opposite.