In her comics, and many other creative pursuits, Lynda Barry has been "beaching her coracle" on the shores of childhood for quite some time now. Whereas most adults, according to Peter Pan author, J. M. Barrie, can only hear the surf from those shores, ever and always Lynda Barry returns in her comics with uncanny vividness to the treasures and terrors that are hidden there.

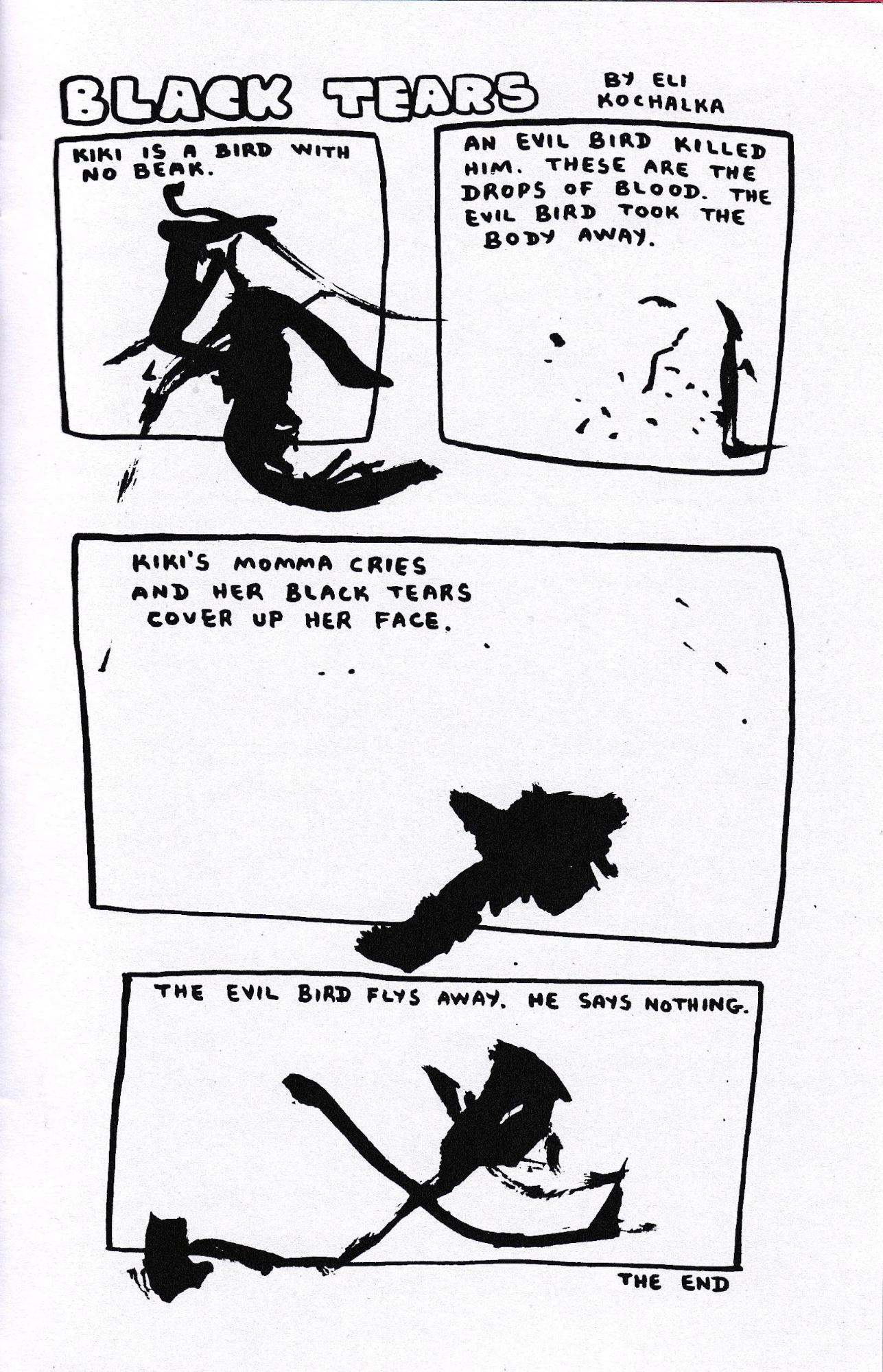

As I began to read through the many volumes of Lynda Barry's comics and guides to creative engagement, I found myself digging through my zine collection for my beloved copy of Two Dead Ninjas. While browsing the Small Press Expo in Bethesda, Maryland in 2007, I came across James Kochalka's table. There I spotted a smallish zine with a bright red cover that had a crudely drawn spidery character dolefully looking back. Inside the photocopied pages were hand-drawn panels filled with lopsided squiggles and strange, barely coherent text. James had set up the panels on the page and let his three year old son, Eli, draw and tell stories which James then dutifully wrote down. There was something emergent, raw, and thrilling in these scribbles. On each page were images of things barely visible, yet strangely present. Inside the splashes of ink I could just make out the drops of blood, the black tears of Kiki Bird's Mother, and the evil bird flying away. I now feel a little embarrassed that I scarcely looked at the other comics on the table. I was so excited at the discovery of this little treasure, that I barely registered the look of disappointment on James' face when I had no interest in anything else. For my neglect to look further I sincerely apologize: sorry James, it was nothing personal, anyone would have been upstaged by Two Dead Ninjas.

Examining little Eli's comic again, I am looking for something in it that helps explain the primal allure of childhood. What's more, I wonder if there is something to be learned from what children conjure without effort? As my guide to all things creative keyed to the music of childhood, Lynda Barry is an indispensable prophet whose smart and sensitive comics capture what is funny and frightening about being a lower middle class kid. Underneath the everyday simple joys and tedium is an unmistakable variety of American poverty that frames the ongoing diminished expectations and general indifference to hardship. But even more than that, they speak in subtle ways about longing and absence with a soulful living presence.

Though her comics are deeply steeped in kid culture, the childhood found in her pages is closer in character to my own upbringing in the 1960s than that of children of the 1990s, when these comics were first made. The obvious absence of cell phones and social media in the comics make them quite different, even now, from the childhood of college students today. Fried baloney sandwiches, bathing caps with rubber flowers, and calling an AM radio station to request a song are just a few of the many things I remember from my own childhood while reading Drawn & Quarterly's new reprints of Ernie Pook’s Comeek. These are things I now scarcely remember, that I do not miss, and certainly have no hankering to relive. The recollections in Barry’s comics are familiar and true to my memory, sometimes even in a startling way, but I feel no large sentimental upwelling of reverie as Proust had by eating a Madeleine. Instead they invoke in me a certain distance, similar to the L. P. Hartley truism, "The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there."1

In their comics Robert Crumb and Bill Griffith have poured forth quite a bit of ink on the themes of a lost and missing American culture that the present times seem to be woefully lacking. Whether it is 78 speed blues albums, roadside attractions, or the tropes of film noir, they are employed in Crumb’s and Griffith’s comics as a way to push back against our current pop culture. Lynda Barry slides easily past that goal toward a more distant place where memories are the impetus for an encounter with something more visceral. This is not a nostalgic turn toward something missing, rather this is a coming into contact with the past in all its messiness and convolution. And now, looking back, some of these things from that time may have slid into focus, allowing us to adopt a more forgiving and compassionate way of seeing the way we once were.

Lynda Barry's comics contain a strong sense of loss and regret from things past. But they are not just about what happened back then. If that were the case, they would only be about "What it IS” (or was). As if to say, this is just what happened back then, and her comics would merely provide us with a window for nostalgic reflection. But as Lynda Barry instructs us elsewhere, she is asking "What IT is." It, that "ancient it,” which she describes as an essence of something that makes one deeply engage, as if "it" were somehow alive. Lynda Barry also refers to that mysterious living “it” as an "image." These images are not her actual pictures or drawings on the page, they are something more like a ghost of a thing that stays with us.

"It's alive the way memory is alive . . . Alive in the way the ocean is alive and able to transport us and contain us . . . Made of both memory and imagination, this is the thing we mean by 'an image'.2

Lynda Barry was introduced to this idea of images in 1974 at Evergreen College when she took a writing and art class called “Images” from Marilyn Frasca. Regardless of whether you wrote or painted, the goal was to find the “image” in the work. According to Barry, Frasca seldom spoke and the class spent a great deal of time just looking at a piece of art. Meanings and interpretations were secondary to the experience of seeing the “image.” To help us understand this experience, Lynda Barry recounts in her book Syllabus that she observed a performance of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet performed with a bottle cap and a cigarette butt as the titular roles of the drama and that these humble objects had “it.”3 The puppet, or the pictures that make up the comic, are not their “images." Images, as Barry would explain, are made of more fragile and tenuous experiences where the thingness of the art, which is merely the vehicle for this experience, drops away and there is something looking back at the viewer.

By attending to art in this manner we are not suspending our disbelief in the puppet or the comic character, but rather our attention to it grants the object a provisional status, and we are in a way acknowledging it as yet another living being in our presence. In this way, Lynda Barry’s comic characters are surprisingly puppet-like, projecting a face and body that rely on approximations of appearances and gestures. And, like puppets, they remain accessible because of their innocence, their lack of history, their simple way of being that we must take at face value.4 Through their innocence we allow ourselves to engage in child-like imaginative play that transforms our ordinary world into something where the deeper truths about the mysteries of life can emerge.

The word “image,” as Lynda Barry uses it, does not exactly conform to any usage I could find in the Oxford English Dictionary. On the contrary, her word "image" seems to be moving in the opposite direction and losing its meaning as anything distinctive or special. An image in the common parlance can be any generic digital file that is simply a copy of something, like the “image” of someone’s hard drive. Reclaiming the word image from its more ordinary usage may prove difficult in the 21st century, where we depend on images being fluid and flowing as an uninterrupted medium that moves seamlessly between devices, providing us a momentary diversion and a refuge from the more urgent aspects of our lives.

Walter Benjamin, back in 1935, warned that we moderns have devalued our Art with the inundation of mechanically reproduced images that have no particular authenticity or authority, and indeed no particular authorship. In the grand narrative of Art, according to Benjamin, these new reproduced works are ephemeral and without consequence, “The public is an examiner, but an absent-minded one.”5 The story of art could thus be written as an arc from prehistoric times, where images were instruments of magic, to the modern times, where mechanical reproduction has emptied out the image of its significance. In many ways I see Lynda Barry’s comics and teachings as a concerted effort to reinvest in the idea that images have a special presence, and to restore their ancient power as magic things.

Barry is not alone in her ambition to reclaim the power of images. Modern artists, such as Paul Klee, rejected all imitation of classical ideas of beauty, and hoped to rediscover a more immediate art through the primitive.6 Klee wrote in 1912:

For these are primitive beginnings in art, such as one usually finds in ethnographic collections or at home in one's nursery. Do not laugh, reader! Children also have artistic ability, and there is wisdom in their having it. The more helpless they are, the more instructive are the examples they furnish us; and they must be preserved free of corruption from an early age.7

Of course, the idea that foreign peoples are primitive or in any way childlike is a wholly unacceptable idea today. The point here is actually more about the distance these things had to conventional ideas of beauty and culture. From Klee’s point of view, established culture was a corrupting force and his idea of Art needed to emerge free from those expectations and restraints. This is not such a strange idea: how many comic art teachers cringe at their students’ imitations of Disney and Japanese manga, and wish to return them to a simpler means of expression without so much baggage.

When examining Lynda Barry’s comics it is notable just how distant her stories and characters are from current ideas of childhood today, but also from the mainstream ideas about kids’ comics, and even distant from the underground comics where her work takes inspiration. They stand apart in ways that seem awkward and counter intuitive and can appear unschooled. They have none of the established norms of kids comics like Nancy, Little Lulu, Peanuts or Calvin and Hobbes, where there is a refined sophistication drawn from the established traditions of comic making.8 Ernie Pook’s Comeek is a deliberately regressive move away from expectations and conventions that may be holding us back from experiencing the more raw “image” within.

Rereading Lynda Barry’s comics today, I am reminded of how inscrutable they appeared to me back when I would have come across one in a weekly alternative newspaper. At the time I regarded them much the same way I thought of the poems I skimmed over in the New Yorker: they required more effort than the comics next to them and it was never entirely evident that they would be worth the time to read. Barry’s comics are indeed like poems, they require extra attention and actively resist the idea that comics should be an “invisible” art or that they should be “easier to read than not read.”9 More importantly, the visual complexity which prevents easy access is not at all like some experimental comics that are merely difficult to read, and where the goal is just visual confusion and excess. I have come to equate the experience of reading Barry’s comics to the Zen koan, “not knowing is most intimate.”10 To approach her comics with the patience they require is to allow for an intimacy where the inherent image lies.

Lynda Barry’s irony and keen observations are somewhat reminiscent of Ben Katchor’s densely ink washed humorous meditations on urban life, but are more akin in spirit to the comics of Aline Kominsky-Crumb and Roberta Gregory, where looser lines and playfully ornate pages display an irreverent spectacle of life as it is lived. Lynda Barry actually employs a couple of different styles depending on which character she is channeling to tell their story. In this manner Barry is following in a tradition first established by the great-grandmother of comics, Emilie de Tessier, otherwise known by her pen name as Marie Duval. Duval drew the character Ally Sloper in the 1870s in a crude childish style which she referred to as a "Sloperian Point of View”11 as if her generally incompetent and outlandish character had taken up drawing his own comic. What separates Lynda Barry’s work from many other comics that are more-or-less only about kids is that in her comics the center of gravity is entirely within her character’s own being and within their own way of seeing things.

Barry’s comics are fundamentally about girls, and following that there can be many affectations of the cute and sweet. The ornamental Virginia Lee Burton like flowers that decorate the title of the comic, the four panels of childish doodles and stumbling letters innocently imply that this is just another kid’s comic. But the girls have opaque glasses, large noses, too many freckles and their frizzy hair is too unkempt to be a fashion, or an attitude: rather it is who they are. Maybonne, the frequent lead in these newly reprinted collections, My Perfect Life; Come Over, Come Over; and It’s So Magic; has little of the plucky wherewithal of Little Orphan Annie, Nancy, or Little Lulu, rather she can be moody and self-conscious and has a strong desire to belong and be liked. While she is not popular, she does have a few friends, and when under pressure, a great squall of tears is sure to burst forth and then disappear like a summer storm. All in all, a fairly normal kid. Lynda Barry’s characters are not an especially anxious bunch, and in this way they differ from the characters of Roz Chast, to whom Barry is often compared. What makes these comics a special joy to read is not the usual kid narratives of overcoming adversity or discovering who they really are; instead, it is the sincere way the kids observe everyday life. Maybonne is sad her favorite uncle, John, has left town because everyone in town now knows he is gay. She writes in her diary, “in the movies by ‘the end’ everyone is supposed to understand each other. That’s why I think the movie of Uncle John and Grandma must be only at intermission.” She is still holding out hope for a happy ending but it will not happen today.12

Opposite Maybonne is her younger cousin, Marlys, a feisty girl who counters Maybonne’s moods with undiminished optimism and verve. Marlys playfully imagines infinite possibilities, taking every liberty a kid her age can. She is constantly inventing games, reporting on school news, and taking command of things way beyond her comprehension. The character is especially beloved by Lynda Barry whom she calls the “imaginary friend I always wanted” and is featured in The Greatest of Marlys collection published in 2016. Marlys is more assertive and outspoken than any other character in Barry’s work. She is quick to dance, fall in love, and impulsively follow her cravings, which often crash against reality. Unlike the rest of us, as an episodic comic character she never grows up and matures from these embarrassing stumbles. Instead, she is allowed to live again and again entirely within the moment of her complete rapture.

Comics suffer from the same plague of cuteness that has swallowed up virtually all popular culture across the globe. This disease has effectively banished all sensibility about how the world really works and replaced it with a weighted blanket of cloying empty sentimentality. But just like the nostalgia that is elsewhere in other comics and so easy to slip into, the cute is elusive prey in Lynda Barry’s comics. The girls gamely play at acquiring and experiencing the requisite quantities of cute and beautiful things, but these efforts are invariably thwarted by the genuine absurdity of the very expectation that such things should be cute, should be beautiful. The girls who effectively wield the power of cute have social and economic advantages over Maybonne and Marlys that allow them to both propagate those ideas and be defined by those expectations. “Girly girls” as Barry calls them are circumscribed into these fixed rolls which severely limits who they can be. As the name "Girly girls" implies, there is an over determined excess and a redundancy in their fabricated identities.

As the girls go about searching for ways to find cute and beautiful things from the Sears catalog or posing and tossing batons like drum majorettes in a marching band, their heart’s desire evaporates even as it comes into focus. Ultimately, the closer we look at Lynda Barry’s comics (and she is always making us look closer), we are drawn into miniature dramas, just as the girls are drawn to their fleeting desires. While reading Barry’s comics we imagine an interior space which is both compelling and inaccessible. The writer Leslie Jamison has compared our experience of miniature things to Alice in Wonderland looking though the tiny door to the garden beyond. For the characters in the comic, this idea of longing is perhaps more akin to Bil Keane’s miniature peephole comic, Family Circus, which Lynda Barry has staunchly defended against the cynics of the RAW generation.13 The distance between us and the garden, or the characters and the tidy kitchen with happy children, is inevitably a place of disappointment, Jamison observes, as “the proximate unruly world comes up against the impossibly curated one.”14 In these busy panels by Lynda Barry that are entirely devoid of solid black or white, the subsequent longing for these out-of-reach spaces is perpetually deferred because we can never actually occupy the space they create. As we witness the characters’ longing for the inaccessible spaces created by the desire for things deemed cute and beautiful, we see the deferral of the girl’s longing encased within our own like one Matryoshka doll inside another.

Much of the visual density and complexity from Barry’s Ernie Pook’s Comeek comes from the word to picture relationships which are consistently skewed toward the written word. The main written narrative over top is either by Maybonne, Marlys, or Freddie, and often strives to find order or to make sense of what is happening and the dialog by characters inside the panel do not allow for any kind of easy resolution. Words dominate the visual space while the characters and backgrounds are often left to inhabit less than half the bottom portion of the panels. Speech bubbles are packed in and around the characters with the unmistakable cadence of the language of kids as they plead, cajole, lie, and bully each other and plot escape from their parents. There is also the occasional extra-narrative commentary (something akin to the editorial "eye-kicks" found in Dick Tracy or MAD magazine) where text boxes with arrows point out details to the reader, for instance, explaining that we are reading a translation from Tagalog, or that her best friend is two years younger and short for her age.

In Lynda Barry’s comics there is never any pulling back in a cinematic manner to take in the whole moment, or to regard the action objectively from a distance. These are invariably close-cropped scenes that peer out around the text in a disorienting way. There is plenty of intimacy and endless searching questions that hang about unanswered, like: What do you write to a soldier at war? What can you do about a creepy dad molesting his daughter? Should you tell on the boy from the Christian Academy that date raped you? Despite the vividness and intensity of the stories, the actual drama happens like a Greek Tragedy that is off stage and out of sight. We see only through the girl’s eyes the implications and complications that arise from events happening elsewhere.

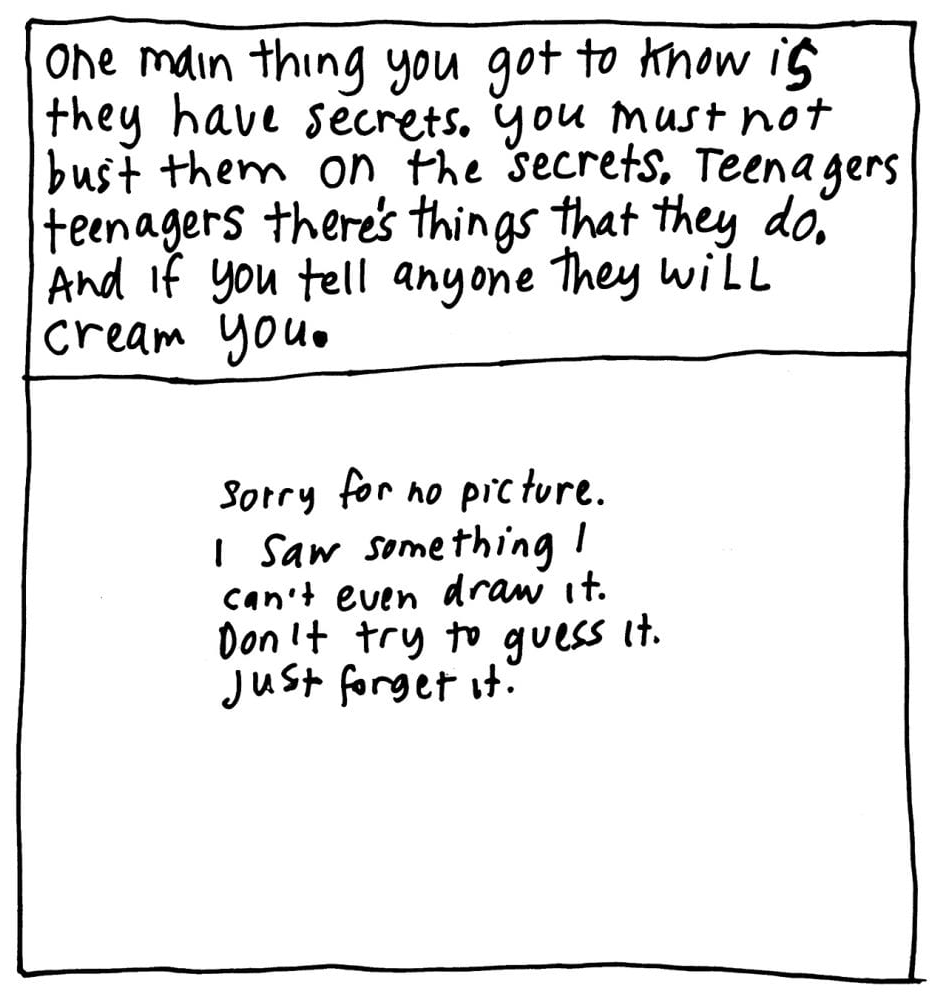

Lynda Barry embraced the liberation that came with the underground comic movement in the 1960s, celebrating the idea that “comics can be about anything,”15 while rejecting the excesses and libertine impulses of many of that generation who used that new freedom to explore their own excessive sexual and violent obsessions. Barry’s restraint is not just modesty; rather, it is an opening to engage in more complex and subtle ideas. This can be seen in the comic when younger Marlys must leave blank the comic panel she is drawing because she was told to forget, and does not want to remember, what she saw the teenagers doing.

The kids in Lynda Barry’s comics are makers and their drawing plays an especially important role in how they interact with the world. Inside her stories drawings have power, they are used as social currency and have the critical function of asserting themselves in ways that the adult world around them otherwise forbids. This idea is beautifully encapsulated in the comic, “The Night We All Got Sick,” in which, after a family visit to a parade, a whole room full of kids become violently ill on the junk food they ate (which, of course, is not seen). Eventually we learn of the lingering memories of that trip where any mention of the food they got sick on that day would provoke a severe reaction. The “secret weapon” that Maybonne uses on her cousin, Marlys, is a drawing of a hot dog, which she claims is, “why I got to be such a good artist.”16 The reoccurring theme of being an artist and being creative allows us to see how the world is seen by these kids. Through their art we can begin to understand how the kids actually make meaning from the events in their lives through the stories they tell themselves and in a way assert some modicum of control over the unruly and arbitrary forces that beset them.

That art has this vital role in her comics is no doubt a reflection of the importance it had and continues to have in Lynda Barry’s own life. This is clearly evident in her teaching philosophy which has been beautifully recorded in her earlier books beginning with What It Is (2008) and Picture This (2009), and more recently in the pair of composition notebook look-a-likes Syllabus (2014) and Making Comics (2019). Altogether, they represent a remarkable and original rethinking of how comics are taught, how they are made, and the value they hold for creative ideation. And like with her comics, hasty readers may be misled by appearances, and think that these guides to writing and comic making are mere kids’ stuff. Yes, they can be rambling and digressive, with busy collaged pages, and with no table of contents or index it is easy to get lost and wander a long time among the colorful and strange pages to find what you are looking for. Yet, despite these perceived challenges, Lynda Barry is well worth the effort.

In the last three years I have read every book, essay, or zine on comic making instruction that I could get my hands on (almost fifty titles in all). And in my opinion her books are beyond a doubt the smartest and most valuable resources I have yet to find. They have profoundly changed the way I teach, and I owe a profound debt of gratitude to Lynda Barry for leading the way out of the unimaginative tedium of comic making instruction and providing clever and subtle ways to bring students toward making original and thoughtful work. Though I have not tried every assignment in these books, I have used many of them in my comic making classes with great success and some I now use even in my Art History lecture courses.

The “instant book review” and the “attendance portrait” are two ideas that have jumped from comic making to my everyday teaching. The book review is an easy tool for getting students to brainstorm quickly about a book and to think about it visually. This is especially useful when I assign comics to read and I want them to interact with the book in a visual way. Drawing portraits for attendance is something I have done for at least five years now and my attendance has never been better. At the start of class, I pass out index cards and they are to draw a self portrait in three minutes with a silly prompt, such as “draw yourself as a scarecrow.” I collect the drawings, and the people who are there to draw get a small token credit toward their grade. I especially like how after three minutes of portrait drawing, everything else that was happening before class is put away, and I have the undivided attention of my students at the start of class.

Lynda Barry’s comic instruction is not simply a how to make comics the Lynda Barry way. None of the results of the comic projects will inevitably result in something that looks like an Ernie Pook’s Comeek. She also has adopted new ideas, such as no-photo blue pencils, from her years of teaching comics that, to my knowledge, she never employed in her own comic making. The mechanics and focus of her comic making instruction, are similar to her work as a comic artist as both are unmistakably handmade things. The students work without fancy pens and paper and never employ any digital tools for making or editing. This lack of technology is a longstanding part of her own artistic practice. Back when most authors were taking up using word processors on their home computers Lynda Barry hand wrote, using a brush and ink, her over 300 page illustrated novel, Cruddy (1999).17 She found the word processor made her too critical and self-conscious of everything she wrote. Hand work to her is an essential component in the process of showing up and seeing what happens and allowing the work to flow out unedited. This idea is explored in the comic 100 Demons (2002), where, for the first time she invites her readers to try drawing with a brush to see what happens to come out.

Lynda Barry is always quick to champion her sources of inspiration and in these books we hear of Ivan Brunetti’s Cartooning: Philosophy and Practice (2011) as an important source.18 Both Barry and Brunetti see comic making not simply as an end in itself, but as a valuable tool in self-discovery and ideation. This notion alone separates them from the vast majority of comic instruction manuals that focus simply on the requisite acquisitions of skills necessary to make comics. The tacit assumption in many other manuals is that the practice of making comics requires a kind of apprenticeship where the tools and skills of the trade are set down. This approach is especially evident in Stan Lee’s How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way19 where there is no discussion of individual innovation or creative ideation.

Barry and Brunetti approach comic making instruction with the idea that many brief, timed drawing activities urge students to be more essential and spontaneous in their work with the hope that they break down any inhibitions or habits about drawing in a “fine art” mode. Brunetti’s simple large head figures with their squat square bodies and dangly arms are the go-to mode of illustration. So that students focus more on laying out the gist of the character and their action. In this way their comic drawing is more about eliminating the barriers of skill and craft and focusing on communicating your thoughts. Despite the early exercises in ideation, in the end Brunetti is a formalist who, like many before him, spends a a considerable amount of time talking about the craft of making a comic. Barry goes further into ideation than Brunetti, questioning value judgements about “bad” art and asking her students to look to the expressive power of more spontaneous creations. Both in Syllabus and Making Comics Barry often offloads decisions about page layouts so students focus more on content, eliminating all of the skill-building exercises where students practice cross-hatching or lettering for its own sake.

For the professional comic artist you may be howling with grief at the persistent march toward the de-skilling of comic art and the inevitable loss of any kind of craft. And to that idea I would reply that they should consider the words of the champion of the Arts and Crafts movement, John Ruskin:

Demand no refinement of execution where there is no thought, for that is slaves work, unredeemed. Rather choose rough work than smooth work, so that only the practical purpose be answered, and never imagine there is reason to be proud of anything that can be accomplished by patience and sandpaper.20

Comics are an especially idea driven art and yet, too often, notions about craft and the expectations of genre drive out original thought as comic artists churn out page after page, which have all the craft of appearing well-made and none of the substance that makes them worth reading. Barry’s comic lessons assert that craft needs to be fostered in the service of ideas and expression, rather than as an end all by itself. The illusion of significant results is not just found in comic making guides but of nearly all art instruction going back to lessons established by the Bauhaus. The enormous impact of the Bauhaus on art instruction was through their way of atomizing every aspect of art making into a system of formulas that could be readily applied to any kind of art. This has led to the common problem with art assignments where the rubric consists of a variety of skills to be learned and students go about their work checking off the requirements. This process is nothing like real art making and in many ways creates the false impression that art making is merely about fulfilling job specifications. While this skill-first approach is an efficient way to learn, what really is needed first is not a collection of skills, rather the student needs to find something to say. The needs generated by an idea should motivate the student to learn the necessary skills to make the idea work. Moreover, comic making is an especially good way to foster ideation. Lynda Barry’s assignments bounce back and forth between drawing and writing in such a way that one activity can spur the other in new directions.

I know these are radical ideas that many would refute by saying that the students have nothing worth saying at first, they also do not understand anything about art making, and their first ideas are impossibly cliché and useless. If that is indeed the problem then teaching them skills first will only make them adopt the outer shell of the work, art that looks like art and nothing else, and they will struggle for years to find how to fill the shell they have created only to attribute meaning to something that is essentially meaningless. The goal should be first to make them more observant and sensitive to the world around them so they learn how to see things through their own eyes, to trust their own senses, and cultivate their memories. Lynda Barry’s class begins with journal exercises, quick drawings, and creative ideation where the students find where their vidid images are hidden. There are a whole host of valuable ideation projects that allow the student to discover images that resonate with them and from those core projects the work eventually emerges.

Another way to see how Lynda Barry’s process is different from other comic making guides is to look at the creation of characters. For Scott McCloud, and really many other books on comic making besides, the character has certain objectives relative to the needs of the story. The comic artist needs to identify the “inner life” or motivation of the character, followed by certain visual characteristics that makes them distinctive, and finally, establish any expressive traits in the language.21 This is quite similar to the way the theatre director Stanislavsky talked about characters. In this way the comic artist plays the role of an auteur director who has a plan for the whole production and must figure out how all the parts work together.22 This is all very solid and sensible advice, but it can lead to certain contrived and conventional ways of thinking as the comic will only be as good as the initial plan. For Lynda Barry the process emerges piecemeal, rather than from an overall plan. The goal is to get inside a memory, or feeling, and respond spontaneously to the needs of the moment. This is a more playful approach that is more open ended and intuitive. Rather than conceive of a whole character in its entirety from the start, the characters are more like collages, or scrapbooks, made of bits of inexplicable and contradictory things.

The potential problem with Lynda Barry’s method is that too often our biases emerge quite forcefully and it is hard to look past the assumptions and stereotypes that are carried along inside our intuition. This was born out in a recent study that demonstrated when viewers imaginatively saw faces in objects (pareidolia) participants of both genders were four times more likely to see the imagined faces as male.23 Such a bias might appear in Lynda Barry’s assignment where a students interpret spontaneous squiggles into characters. The implications of this study underscore the limits to intuitive construction and the need for multiple approaches to comic creation and editing. Lynda Barry's process actually has a generous amount of reiteration, so that students do not become too attached the first thing that comes out of their heads. She allows for a separate editing phase, whereby only a few of the dozens of hasty sketches are developed further into more finished works. She also encourages her students to work on each other’s drawings, to take on each other’s characters, in a way to make the student look outside their own preoccupations.

From these books on comic making we learn how to discover and experience “images,” which are not our interpretations or our thoughts about things, rather they are just below our cognition in what she calls “our unthinking mind.” We need to trick our selves to let them happen and often these images are reconstructed from many things we cannot fully identify or understand. Lynda Barry’s idea of the image is in some ways similar to the classical idea of the eidola, that refers mostly to a representation of another person, but in a phantom-like manner. Eidola is the root of the word pareidolia (mentioned earlier) with the prefix “par” which means a false image. To the ancient Greeks eidola were something like shadows that were cast off from things we experienced that later became lodged in our body till they were revived in our dreams. As Heidegger points out our knowledge of the world, like eidola and Lynda Barry’s images, are embodied through lived experiences and often exist inside us as a non-verbal memory.

So, why is childhood such a rich repository for these image/eidola? It might have to do with how children play and how they are are especially open to the impulse to play. Children have only a limited access to and understanding of the adult world and that distance Heidegger would call “presence-at-hand,” where things are new and out of reach. This condition is in contrast to the adult world where things are largely “readiness-at-hand,” or available for use, and where they often become an invisible extension of ourselves. The shoes on our feet are in the state of readiness-at-hand because we depend on them without really being aware of them.24 Their utility is a condition of them being an invisible extension of ourselves. Presence-at-hand is where we have an ambiguous relationship to things and we explore the possibilities without having a full understanding. If we are making a painting of our shoes, as Vincent van Gogh did, we are searching for meaning and they no longer function invisibly. We are looking for what shoes are and how they fit in our perception of the world. Artists are so often inspired by children because they too need to adopt a presence-at-hand point of view so they can see things as if they had never seen them before.

Many other researchers and philosophers are trying to understand the role of play in our lives. Ian Bogost in his book Play Anything (2016), asks us to put aside our irony, meta commentary, and cynicism and reengage in “anything.” He writes, “We expect meaning to originate from within ourselves as if we fully understand our thoughts and intentions.” Rather, he says, “the solution is not within us it is everywhere and everything else.”25 In a similar way, through our play at comic making, with Lynda Barry as our guide, we are asked to focus outside ourselves and pay attention to the drawing looking back at us.

A drawing may come from you but it exists apart from you in both matter and meaning to others. When I look at a drawing I’m not thinking about the person who made the picture. I’m meeting something. And it’s also meeting me, if I can stand it.26

Perhaps what Lynda Barry means by, “if I can stand it,” is that awkward and disorienting feeling we get from facing an image in a work of art, which can be like meeting someone for the first time. How easy it is today to slip on headphones, check Instagram or TikTok; anything else would be easer than to engage with this unknown person. As we “curate” our lives, or they are curated for us though invisible algorithms, these encounters with something outside our acknowledged sphere of relevance are becoming more rare and more fraught. Even as the world has opened up to us through these digital means we are now more anxious and cautious about what we allow ourselves to experience. In a similar way, many years ago, when I might have passed on the chance to read Ernie Pook’s Comeek, today I would tell my younger self: “slow down, make yourself vulnerable to things you do not understand. There is more here than what meets the eye.”

The reason we need to take the time to read Lynda Barry carefully is not because childhood is an ever shrinking territory that needs our protection, or that we need to ever prolong our adolescence, or even that childish play has some utility or practical purpose in our lives; we need to do this because these comics reveal an innocent and heart-felt way of being in the world, and they allow us an opportunity to experience those things that are now just out of reach.

* * *

- This quote is from the first line in L.P. Hartley’s novel The Go-Between, from 1953.

- What It Is p.14.

- Syllabus, Drawn and Quarterly, 2014, p. 15.

- Kenneth Gross’ Puppet: An Essay on Uncanny Life, University of Chicago Press, 2011, is a beautifully written book on the experiences found in puppet performances and my thoughts here are in part inspired by his work.

- “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Translation by Harry Zohn, 1935.

- Primitive here simply means "prior in time,” but it has so many pejorative connotations that it is impossible to use without careful distinctions and caveats. I use the word here because it has important implications in the history of these ideas about images of the past. For example, there is a long history of artists taking on the mantle of 'primitive' having been inspired by the art of the preliterate and premodern societies from places across Africa, Americas, Asia, and the South Pacific. Primitive has also been used to describe the art of children, unschooled outsiders, and emotionally disturbed people. None of these people consider themselves, or their art, as especially primitive and the outside fascination with their work as “primitive” has always been less about the work itself or the artist who made it and more how a viewer sees themselves in relation to the “primitive.”

- Ernst Gombrich, The Preference for the Primitive. New York, Phaidon Press, 2006, p. 261.

- See How to Read Nancy by Mark Newgarden and Paul Karasik for a master class in the finer details of Ernie Bushmiller’s craft.

- Scott McCloud’s notion of comics is that the artifice is hidden or “invisible” and Ernie Bushmiller’s comic Nancy was said to be easier to read than not read.

- I am indebted to Ruth Ozeki who mentioned this koan in her interview with Ezra Klein on 1/25/22.

- Marie Duval, 16 Feb 1876, Judy Vol 18, page 185. Reprinted in Simon Gennan, Roger Sabin, Julian Waite, Marie Duval. Myriad Editions, Oxford UK, 2018: p. 14.

- It’s So Magic, p. 47.

- Critical Inquiry, Spring 2014, "Comics & Media," edited by Hillary Chute and Patrick Jagoda.

- Leslie Jamison, “Small Talk, Leslie Jamison considers our love of the minuscule.” Times Literary Supplement, July 9, 2019.

- January 2nd, 1989, Interview with Thom Powers.

- Ernie Pook's Comeek, “The Night We All Got Sick,” 1986. Reprinted in The Greatest of Marlys, Drawn and Quarterly, 2016, p. 6.

- Pages of her Cruddy manuscript can be seen in Drawn and Quarterly.

- Ivan Brunetti, Cartooning: Philosophy and Practice. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011.

- Lee, Stan, and John Buscema. How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way. Paw Prints, 1978.

- John Ruskin, “The Nature of Gothic,” originally published in 1853, republished in John Ruskin: On Art and Life, Penguin Books, 2004.

- Scott McCloud, Making Comics: Storytelling Secrets of Comics, Manga and Graphic Novels. New York: Harper, 2006.

- Stanislavsky’s three books on acting, An Actor Prepares, Building a Character, and Creating a Role, have had a huge impact on American acting which has led to the wide dissemination of these ideas.

- Karen Hopkin, “Does This Look like a Face to You?” Scientific American, March 25, 2022.

- Martin Heidegger, Being in Time: A Translation of Sein und Zeit, trans. Joan Stambough, State University of New York Press 1996, 60-75.

- Ian Bogost, Play Anything: The Pleasure of Limits, the Uses of Boredom, and the Secret of Games. New York: Basic Books, 2016, p. 54.

- Making Comics p. 102.