Tezuka’s pseudo-recantation was not limited to this last panel.

Note how, on the previous page, the scintillating-versus-boring panel comparisons have practically nothing to do with Fukui’s manga. The things that Tezuka had denigrated in the previous chapter of Manga Classroom – the simple FX panel, the cloud-only panel, the sequential close-up – none of them appear here. What the Professor is being forced to admire are, on the contrary, types of dramatic staging used frequently in Tezuka’s own work. Some apology this is. Asked to rethink his opinions, Tezuka instead takes the opportunity to promote himself by way of showing how things could be done better. What cheek to put the self-praise in his competition’s mouth.

As noted last time with regards to Crime and Punishment (Zai to bachi, 1953), Tezuka often employed suspenseful breakdowns reminiscent of future komaga-gekiga, but simply as one element in a diverse storytelling system that included slapstick, tableau-like panoramic shots, and temporally stretched panels that choreographed multiple characters, actions, and events within a single frame. The late 40s and early 50s were years in which he was most heavily under the influence of Disney comics and Disney movies. Accordingly one finds in his work a strong emphasis on animating the image through characters’ bodies and caricatures of movement. Tradition holds that cinematic techniques are the foundation of Tezuka’s work, but that is not the case. One might say that, for Tezuka, the breakdown was secondary to cartooning, with cartooning here meaning the creation of the illusion of movement in space and time through the graphic animation of line and bodies. The opposite would be a situation in which line and bodies are fairly static, with drama and dynamics instead created by layering multiple bodies and objects in a single panel (like in Matsumoto’s recessional spaces) or across multiple panels (like in Fukui’s simplified breakdowns). Such alternatives will be discussed next time.

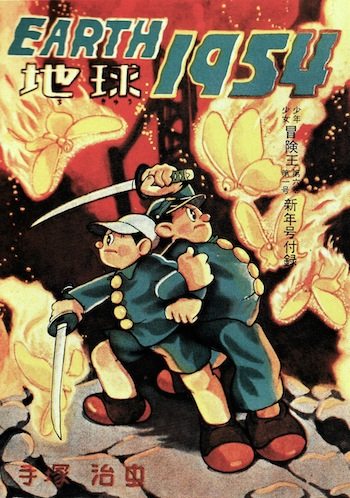

While the Fukui Ei’ichi Incident marks a collision between Tezuka’s cartooning and a new breakdown-oriented mode of comics-making, it also expedited a shift in Tezuka’s own practice away from a Disney-dominated aesthetic and towards what might be termed a form of “cartooned breakdown,” in which the sort of “new expressions” foregrounded by Fukui’s and others’ work are reincorporated into Tezuka’s home turf of caricature and animation. That is what one is seeing in the second installment of “New Modes of Expression.” It is also what one sees in Tezuka’s Earth 1954 (Chikyū 1954, subsequently released as Demon of the Earth (Chikyū no akuma)), which was published notably as a furoku premium (the format that is supposed to have resulted in lazy comics), notably for Adventure King (the same venue as Igaguri kun), and notably in January 1954 (meaning Tezuka must have drawn it soon after his Manga Classroom misadventure in the fall of 1953).

The 128-page Earth 1954 is considered a highlight in Tezuka’s post-atomic antiwar oeuvre. A rural village fights the construction of a monstrous subterranean city, which is ostensibly constructed as the future habitat of a civilization under constant threat of nuclear annihilation, but actually as an impregnable fortress for the purpose of world domination. For the present essay, the significant features of the manga lie in its collateral details. In a move that, given recent interpersonal tensions, can only be called ingratiating, Tezuka names three supporting characters after irritated friends: Baba (as in Noboru), Takano (as in Yoshiteru), and Fukui. The sons of Fukui, who is a village leader, are the manga’s heroes: Eiji and Eizō (Ei-2 and Ei-3 in kanji), after Ei’ichi (Ei-1). Some images of the village clearly come from Baba’s work, and those of exaggerated fighting broadly evoke Fukui’s world. Earth 1954 might be science fiction in Tezuka’s typically apocalyptic vein. But the rural Japanese setting and the average schoolboy heroes (Tezuka preferred robots, animals, and upper-class prodigies) were surely introduced to make amends with his colleagues.

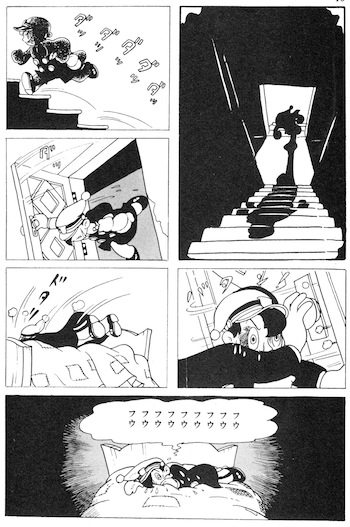

If this wasn’t enough, in the first third of Earth 1954 Tezuka deploys each of the “artistically effective” panels and a number of the criticized “new expressions” from Manga Classroom. In a driving scene, one Doctor Takano appears behind the wheel in extreme frog’s eye view. In a fight scene, a body careens toward the viewer before crashing through the panel frame.

In another fight scene, less-effective lateral action is juxtaposed with the more dynamic configuration of a body flying backward into space (embellished with some Popeye-esque action and FX).

And then, the clincher, the page in which Mr. Moustachio (Hige Oyaji) finds and picks up a pachinko ball, first shown from the side spotting it on the street, followed by a close-up of it in his hand.

Taken individually, these scenes differ little from those in previous Tezuka comics. Taken together, along with the gratuitous casting of Fukui, Baba, and Takano in supporting roles, it’s hard not to read them in relationship to Manga Classroom. One suspects, given the course of events, that they were meant particularly for Fukui’s eyes. Intended as another half-assed apology, perhaps. But, as noted before, because these were techniques associated more with Tezuka’s work, their assembly here becomes a demonstration of how “new expressions” might be more effectively used in the furoku format by someone else, in other words, by Tezuka, by Professor Anything and Everything, versus the various Misters Only This or That who populated the manga industry. Whatever his many merits as an artist, Tezuka cannot be commended for his sense of propriety.

Who could have foreseen that such petty personal squabbles would change manga so fundamentally? Matsumoto, Tatsumi, and many of the other Hinomaru Bunko artists closely read Tezuka’s work from this period, so closely that direct appropriations from works like Earth 1954 frequently appear in the early works of komaga-gekiga from 1955-56. Moreover, the “cartooned breakdown” that one finds in Tezuka’s work from this period – that is, the exaggerated visual effects that Tezuka had begun using in greater quotients to spectacularize his narratives as part of his re-appropriation of Fukui’s adaptation of his own cinematic techniques – became a model for the general economy of storytelling for many of the early komaga-gekiga artists. What this means is that komaga-gekiga derived not only from Tezuka’s inventive genius, but also his arrogance and his uncontrollable compulsion to show off. How often has jealousy been the mother of invention?

What was easy artistic performance for Tezuka, however, was for Fukui a matter of life and death. If this tale already boasts a number of unsightly turns, its ending is patently unhappy.

(cont'd)