Komaga, like gekiga, was natured by two genres: martial arts and mystery. In 1955-56, Matsumoto and Tatsumi both drew a number of judo manga in which the core principles of komaga-gekiga – thoroughgoing cinematic camera work and editing, a heavy emphasis on visual breakdowns versus dialogue, the use of sound effects to fix the short duration of each panel and increase affect – are in evidence. But as these techniques were deployed primarily to induce in the reader the effect of suspense, it is first to the mystery genre that we should turn.

Let me begin here by pointing out that the shaping power of genre is neglected in manga historiography. Formal techniques and their development are typically described as having arisen either by spontaneous artistic inspiration or through the domineering influence of other media. Komaga and gekiga can both be faithfully described as driving at a more strongly cinematic style. However, reference to the artists’ cinephelia or a tradition of “cinematic techniques” in manga alone cannot explain how or why Matsumoto or Tatsumi opted for the styles that they did. If humor was rejected, exotic angles and extreme sound effects explored, and a careful controlling of the reader’s experience through aspect-to-aspect breakdowns pursued, it was because Matsumoto and Tatsumi saw in these cinematic features a way to create effective works in the specific genre of mystery. The lasting appeal of a cinematic style was in its ability to induce shock and suspense in the reader.

Matsumoto was probably the first Japanese cartoonist to make the cinematic the basis for an all-encompassing and exclusive style. Various cinematic techniques had appeared regularly in Tezuka’s work. This is well known and endlessly repeated in writing on manga. While recognizing scattered precedents in the prewar period, Tezuka’s work still today serves as the basis for arguing for the spread of the cinematic across many genres of Japanese comics in the postwar period. Actually, without the rise of komaga-gekiga in the mid-late 50s and its inundation of mainstream manga in the 60s, cinematic stylization was unlikely to have became as pervasive in Japanese comics as it did. After all, for Tezuka the cinematic was just one mode amongst others, and not necessarily a privileged one.

Tezuka reveled in heterogeneity. He loved the comic effect of mixing suspense with humor, techniques of reader-suturing with techniques of reader-distancing, and controlled detail-to-detail breakdowns with full-page scenes implying no specific temporal duration. In the Tezuka books that Matsumoto and Tatsumi read in the early 50s, works like Crime and Punishment (Zai to bachi,1953), divergent modes are masterfully choreographed. The page showing Raskolnikov, cast in shadows, dashing up the steps to his room after having killed the old lady is often cited as a precursor to the noir-ish use of cinematic techniques in kashihon gekiga. But note that it immediately follows a sequence composed of Lotte Reiniger-type shadow cutouts (probably via Yokoi Fukujirō’s Tarzan books) and precedes a slapstick action sequence derived from Disney comics. There is little doubt that young Matsumoto and Tatsumi referred to Tezuka’s work for instruction in how to create suspenseful breakdowns. However, what Tatsumi hypothesized about Tezuka in an interview for Ax in 2008 – “had he continued to create books rather than shifting to magazines, he would have no doubt headed in this [gekiga] direction” – conflicts with the art historical record. Had Tezuka continued creating books, he probably would have continued in the variety mode of Crime and Punishment. It was, in fact, the unforeseen rise of kashihon gekiga that urged him toward purer genre stories. Even then, humor is rarely more than a page or two away.

Humor was a major casualty in the emergence of post-Tezuka comics in the early-mid 50s. Since the 30s if not earlier, children’s manga typically shared the same mode of expression despite being about different things – ninja adventures, samurai battles, war stories, expeditions to treasure island, trips to the moon – something that continued through postwar akahon. In the early 50s, magazine, retail hardcover, and kashihon manga alike begin to show signs of developing distinct styles based on subject matter. In this context, humor was a problem not so much because it made things frivolous (the usual claim, voiced by Tezuka, Tatsumi, and Matsumoto alike), but because it was the great equalizer. For decades it had (with notable exceptions) asserted a single genre over kids’ manga regardless of setting and costume, and now with gentrification that was about to end. Sugiura Shigeru’s work shows how that giddy anything-goes mode could only survive by going insane.

Humor was doubly problematic for the various subgenres grouped under mystery: crime, detective, thriller, and horror. Thanks to the rising popularity of mystery in juvenile and adult fiction as well as in the movies in the 50s – an inheritance from the prewar period that was much strengthened by true crime pulps during the Occupation and the mass translation of French, American, and British mystery novels in the 50s – it was precisely these subgenres that defined kashihon gekiga and komaga. While martial arts manga also played a part, it was primarily the demands of mystery that set the stage for Matsumoto and Tatsumi’s selective cannibalization of Tezuka. In retrospect, one can see how Tezuka’s late Occupation-era manga – each book offering a kind of variety show of genre effects held together by a leitmotif of humor – embodied this transitional moment by being (to borrow from Matsumoto’s above description of akahon) an “overturned toy box” of gags and effects, whose heterogeneity also facilitated genrification by providing an arsenal of “story-for-story’s sake” techniques. Komaga, like gekiga after it, chose one toy out of Tezuka’s playroom – the cinematic techniques of suspense – and not only dismissed the rest as belonging to the supposedly childish world of fun and games, but endeavored to recontextualize cinematic suspense so that it no longer harbored the potential for humor, as it had in Tezuka, in the form of exaggerated spectacle and caricatured affect. I say “endeavored” because, as we will see next time, there was a fine line between cinematic power and cinematic spectacle, a line which even Matsumoto and Tatsumi playfully exploited.

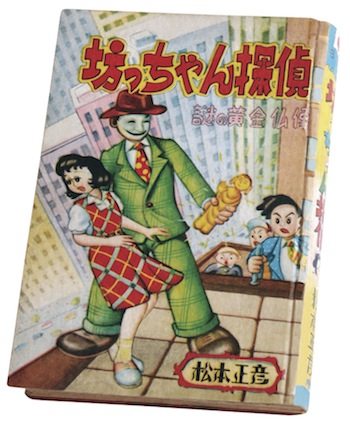

Back to Matsumoto’s career. His first non-humor book was his fourth: Kid Detective (Botchan tantei, March 1954). Like many of Matsumoto’s early mystery books, the story of this one is heavily indebted to Edogawa Ranpo’s famous juvenile mystery series, “The Youth Detective League.” Matsumoto was also a professed fan of Yokomizo Seishi’s writing and the Tarao Bannai series of detective films, both of which were major influences on nascent komaga-gekiga. But some of the central plot motifs of Kid Detective and other early Matsumoto mystery manga – the near-miraculous theft of expensive art objects, the villain’s costumes and daring escape by balloon, the judo master detective – have been clearly culled from the most famous books of Edogawa’s Lupin-esque series: The Man of Twenty Faces (Kaijin nijūmensō, 1936), The Youth Detective League (Shōnen tantei dan, 1937), The Fairy Doctor (Yōkai hakase, 1938), and The Bronze Demon (Seidō no majin, 1949). As we will see below, the importance of Edogawa went further than simple motifs: Matsumoto’s metered breakdowns (one of komaga’s core traits) were polished in an attempt to reproduce Edogawa’s suspense.

Soon after opening Kid Detective, it becomes evident that Matsumoto set out in the mystery genre with a distinct aesthetic in mind. The stylistic shift from his humor books is drastic. The very first page of the story proper presents a breakdown that links two elements that would become key in komaga: the low-angled shot and the metered breakdown. The former will be treated next time. Here let’s consider the latter. The metered breakdown on this occasion takes the form of a pseudo-filmic spectacle: the breakdown of a scene conceived as a single continuous shot into multiple regularly-spaced frames. What’s important about this page, more than it’s obvious nod to cinema, is how it implies an internal metering. Given our somatic familiarity with walking, the boy’s gait and pace can be more or less imagined and felt. One presumes the gait to be regular, something suggested further by the breakdown’s division of his progress into three roughly equal segments. The middle two panels distinctively show the boy in mid-step, at the point when weight is shifted from one foot to the other, implying a footfall in the space covered by the gutter. There is thus, even though it is not directly depicted, a rhythm to the breakdown that is not only visual but also aural.

This type of walking image appears repeatedly in Matsumoto’s subsequent work, sometimes expanded to four panels, sometimes abbreviated to one. What’s different about this early example is the conflicting temporalities of the text and the image: while each image suggests a split-second capture, the text really implies no duration at all. It might be inside the same frame as the image, but the two do not form a single picture. Later, Matsumoto will typically opt to align image and text and synchronize their temporalities, specifically by making text reiterate the metering implied by the depicted action, usually in the form of sharp sound effects or brief vocal cries. This is prefigured by the implied footfalls (a nontextual sound) in the opening page of Kid Detective. What we are seeing here is a nod to cinema, yes, but more importantly the association of the cinematic with metered time. The implication is that the breakdown is a kind of clock, with the passage of time evenly measured by the panels, and with that measuring marked visually and aurally. Frame and footstep together go: panel-tok, panel-tok, panel-tok.

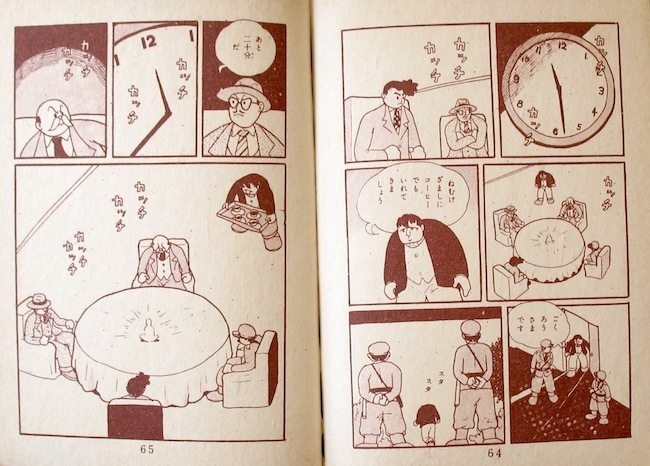

Later sections of Kid Detective hint at a more complex and versatile form of metered breakdown: the metered montage. This form of metrical breakdown is more common in Matsumoto’s work than the above filmic breakdown, which is as much a visual spectacle for it’s own sake as it is a narrative device. The metered montage, in contrast, makes drama out of the passage of time itself. It is suspense on a stopwatch, and timepieces themselves oftentimes appear. In Kid Detective, this only exists in nascent form, with the introduction of a clock within a montage designed to impart mystery. The passage in question begins with a framing shot, showing the city at night. Note the clock tower. The second panel is also a framing shot of sorts: it reiterates the specific hour (barely legible in the first panel) through a domestic wall clock, which serves the double function of relocating the scene in a private residence versus the noir city in general. These clocks only tell time. They do not, as clocks do in subsequent Matsumoto works, count time. However, by coupling the clock with a certain time of day – the middle of the night, the witching hour – even these scene-framing clocks are implicated in the creation of a feeling of mystery and suspense.

Not having access to Matsumoto’s entire oeuvre, I cannot say when he first introduces the metered montage. But by The Mannequin Gentleman (Ningyō shinshi, November 1955), it has become a focal point of the story. Matsumoto’s Lupin-esque villain has vowed to steal a golden idol from a rich collector’s home at a specific time of night. The police have not only surrounded the house, but also the table on which the statue is placed. All eyes are open. Absolute vigilance is established. Yet still the gentleman thief manages to swipe the idol without their knowing. The scene, as well as others in The Mannequin Gentleman, is almost straight from Edogawa Ranpo’s The Man of Twenty Faces.

The important feature here is the proliferation of clocks and faces. Clocks now are no longer simply for introducing the setting’s hour. They do that, but redundantly. The important thing is that they continue to tell time, and at progressively smaller intervals. Clocks are repeated not to express the passage of time, but its approach. The witching hour creeps closer and closer, and the closer it creeps, the more acutely it is felt. That Matsumoto’s goal here is to capture the phenomenological experience of time, and specifically that of time’s anticipation, is clearly expressed on his characters’ faces, of which there are many.

Matsumoto establishes here something important for komaga-gekiga: the image of a face or an eye looking is the image of an embodied mind experiencing time, typically with anxious anticipation. It should go without saying that the goal here is to create a correspondence between the characters’ experience and that of the reader. As the detectives keep looking up at the clock nervously awaiting the thief’s arrival, so readers are forced to keep returning to the time by repeated insertion of clocks into the breakdown.

Given this type of scene’s prevalence in komaga-gekiga, it is useful to give it a name: time-watching, or chronoscopia, by which I refer both to the diegetic image of characters watching the approach of an hour or an event, and the act of reading privy to this watching. Such chronoscopia will be a key element in Matsumoto’s development of a style of comics that, in the name of inducing suspense, will use the panel breakdown to manipulate reader experience like no manga before.

Chronoscopia is not solely a matter of the eye. Note, in the same passage from The Mannequin Gentleman, another feature: the use of sound effects to mark time and define duration. The montage of faces and clocks only implies specific duration in certain combinations: specifically the shot-counter shot pattern of a face looking upward or downward, juxtaposed with the clock or watch that the face was looking at. There is kind of “afterimage” effect in such passages, in which the image of time in the clock panels carries over into the face panels. But once this back-and-forth stops, and the breakdown moves on to depicting other things, the phenomenological feel of time’s passage becomes radically less acute, if it does not vanish all together. Sound effects offer a way to overcome this limitation.

The shot-counter shots of eyes and clocks are often leitmotifs for pages that, taken as a whole in themselves, do no imply a singular rhythm of passing time. This is solved with the insertion of small sound effects of ticking, through which Matsumoto establishes a means to define temporality and rhythm without directly depicting the clock itself or its contrapuntal image of time-watching. Through the sound effect, the visual image of time-watching (the clock, the face) becomes an “auditory image” that, by virtue of being divorced from vision (a sound can be heard without its source being seen), is able to travel across panels that depict things other than clocks and faces. The ticking makes the image of the clock more mobile, and as such is able to infuse the breakdown more generally with the presence of anticipated time. It also imparts the panels with a specific duration – the duration of the clock’s ticking second hand – that, even when the ticking fades out after a panel or two, nonetheless continues to reverberate throughout the breakdown. This after-echo of sound (an auditory afterimage) reminds the reader that the breakdown is continuously metered.

This metering, it is important to point out, need not be regular. In fact, better that it not be. No manga artist, to my knowledge, has attempted something like High Noon (1952)or Christian Marclay’s The Clock (2010).The filmic breakdown, which typically implies a regular division of time, is only used in isolation for spectacular effect or for establishing a zero point of chronoscopic reading. Yet it is only by being irregular that metering effectively captures the phenomenological experience of time, which as we all know is subjective and contingent on mutable physical and psychological factors, despite the fixed metrics of clocks. As noted before, Matsumoto acknowledges this by depicting the approach of time as one of decreasing intervals: the closer an hour approaches, the more intensely time is felt. He also gravitates towards contraptions that provide spatial analogues of this effect.

The most common such contraption was the activated train crossing.

(cont'd)