The Cisco Kid in Yugoslavia

In the '60s, Yugoslav readers of the daily Vecernje novosti (with average an circulation of 150,000 copies) were quite familiar with The Cisco Kid. For many years, it was published regularly with Stan Drake's The Heart of Juliet Jones, John Cullen Murphy's Big Ben Bolt and George McManus's Bringing Up Father, all syndicated daily strips by King Features Syndicate. Hence, readers of a socialist country had, via the first daily with tabloid style journalism, quite an opportunity to enjoy a variety of genres: Western, Soap Opera, Sport, Adventure and Humor. Since the '50s comic culture (domestic and imported) was flourishing again after the golden '30s, this provided a significant form of entertainment. Importantly, the quality of the print was good and there was neither editorial nor technical reason to intervene with the integrity of the daily strips. The Cisco Kid had a chance to be read in the full glory of its drawing style.

Regrettably, in the '70s and '80s, most of the publications in Yugoslavia that were collecting entire episodes of The Cisco Kid (in comic or book form) were of much poorer printing quality with lamentable reformatting. Even the two hardcover books with complete episodes of The Cisco Kid, published in the mid-eighties were published in a modified format. Instead of the original look of the daily strips they added additional panels, destroying the integrity of José Luis Salinas’s drawings, to make pages with six panels per page, cutting or expanding panels, filling in repositioned artwork. This became the usual practice in publishing The Cisco Kid worldwide.

Beginning & before Cisco

The Cisco Kid is one of the famous “eternal” Westerns, appearing on the pages of American newspapers for eighteen years, which can be considered a short period for a syndicated comic strip. In the world of comics done for King Features, many series lasted for more than half a century. The editors of KFS knew pretty well whom they were engaging as an artist for this series. José Luis Salinas (1908-1985) was an extremely skilled comic artist and illustrator. Prior to The Cisco Kid, he showed his extreme craftsmanship in a series of strip adaptations of well-known classic adventure novels in collaboration with the writer José de España. More importantly, Salinas was the author of the masterful Hernán el Corsario (1936-1938; 1940-1941; 1945-1946), which absorbed a lot of creative influence of Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant. Hernán el Corsario is considered the first great comic series in Argentina. Salinas was a quick-drawing artist. This proved to be important in nearly two decades of work on The Cisco Kid which was an exclusively daily strip. It’s one of the few syndicated comics where one can hardly notice variations in drawing quality.

Narrative tone

The lightness of the narrative tone, with elements of exaggeration that verges on the comic, is immediately established from the first weeks of The Cisco Kid. Were the King Features Syndicate editors the ones who set the task of simplifying the story in The Cisco Kid? Yes, there was a warning that Cisco’s character always had to be good. It created a somewhat narrowed space for individualization of characters. It’s divided between good guys and bad guys, providing a certain naivety ready-built into the storyline.

And what about Cisco? There is a certain almost boyish enthusiasm in his character. Cisco is partly based on a humorously simplified characterization. He is an indisputable hero, a young man with a well-shaped, tight waisted body, always dressed in the same embroidered black shirt. A more ironic reader would have called him Narcissus. He is tirelessly flirts with women, and then triumphs against desperados. Cisco’s romantic vision of falling in love is not exclusive and focused upon only one woman. He is primarily attracted to falling in love, to flirting as such and it doesn't matter if his sympathies overlap partners in real time. That brings a certain element of self-parody. Despite the Latin, partly frivolous Prince Charming appearance, sooner or later, he provokes trust and a feeling of protection for women. However, there are very little sexual undertones coming to the surface, if we compare it with other comic classics (Prince Valiant, Casey Ruggles, Lance, The Heart of Juliet Jones, and most of Alex Raymond’s work).

Characters in The Cisco Kid act as if they are on stage, with characters talking with each other as if it is intended more for the reader than for the strips protagonists. Dialog and content in thought balloons are, at times, too explanatory. Some elements of plot are not always convincing enough. Evil men are not evil enough, or they behave in a slightly naive, apparent way, and sometimes they are just plain stupid. Evil demands fascination.

To satisfy

“Reed kept his scripts light in tone, but with enough action to satisfy the Western fans of the day.” (David A. Roach in Paul Gravett’s 1001 Comics You Must Read Before You Die 2011) Part of the problem, I believe, is hidden in that part of the description - “to satisfy”. Hal Foster or Warren Tufts did not tell their stories to please the audience. Lightness of tone was not what they were aiming in their storytelling. Some of the stories were tragic, brutal, uncompromising… and, hence, unforgettable. Not in Rod Reed’s approach, which was less profound than in his stories for the Rusty Riley daily strips (Sunday pages of Rusty Riley were written by Frank Godwin’s brother Harold). The Cisco Kid did not have the epic story power of Prince Valiant or the radical narrative breakthroughs we encounter in Warren Tufts’ Casey Ruggles and Lance. Murder, rape, a woman who leaves her white husband and opts for a Native American to live with is difficult to imagine happening in The Cisco Kid.

Maurice Horn in his book Comics of the American West (1977) describes The Cisco Kid as an old-fashioned Western. That's partly true. In spite of interesting story lines and basically good characterization, the concept of entertaining narratives appeared as a limiting factor. The desire to please the audience did not pay off in this regard. It proved, however, a two-edged sword for the fate of this exceptional series. The Cisco Kid was doomed to be partly conventional. Horn says that after Warren Tufts’ Casey Ruggles and Lance, “Any hope of a realistic, hard-bitten portrayal of the West in newspaper strips went down along with it. … it might seem paradoxical to see the Western strip flourish in all parts of the world while it is slowly dying in America… the American newspaper strips have almost completely abandoned adventure and action…”

Gestures in The Cisco Kid are sometimes a bit reminiscent of the epoch of the silent film, when cinematic innocence prevailed in relation to a method acting: ostensible, manifestly demonstrative, slightly too obvious. Body language, especially Cisco’s, is theatrical. Gestures and faces as well. Salinas’ great talent for capturing facial expressions is subordinated to the demands of the story. However, many other aspects of Salinas’ artwork are not. They go beyond, far beyond.

Elegant & wild

Salinas developed a brilliant technique, shading with hatching. A master of linear shading, he very sporadically using crosshatching; adding gray zones with simple evenly distributed points. His clean line work is on the edge of being mysterious because of its astonishing precision. There are no disquieting strokes of the pen or brush, no simplified bodily shapes. Even from a far distance, Salinas’ miniature figures look flawless. No reduction in drawings, no abstraction: Academic realism in full splendor and glory. It's the reason Dennis Wilcutt called Salinas the Hal Foster of the daily newspaper strip (Return To A Vanished World - The Cisco Kid, Volume 1).

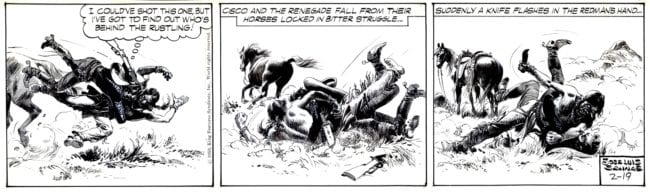

Here comes the paradox of Salinas’ talent: Most of the artists that apply academic realism in comics have a tendency of falling into a certain static approach. It’s difficult to retain perfectionism of drawing and still remain flexible in movement of the characters. What is astounding is Salinas' ability to simultaneously create a filigree work and bring an explosive energy into the drawing. Even the big masters of drawing can often only do one of these two things. Not many artists have the power to be elegant and wild at the same time.

From the saddle down

The principle of freedom for Cisco and Pancho is riding to adventures in the wide-open spaces of the American West. It’s poetry of open spaces. That is one particular layer in this comic strip that has absolutely never been restricted by conventionality. The freest living beings in The Cisco Kid are full-blooded stallions that move to the vastness of the West. Therefore, The Cisco Kid deserves careful reading “from the saddle down”. Right there, seemingly on the margin, all the strength of the action makes Salinas' drawings burst out. Horses are perfectly drawn with pure poetry of movement. With artist and dear friend R. M. Guéra I spoke repeatedly about one particular aspect of drawing skills in comics – who is able to draw a horse masterfully? Among many masters, one would always pop up first in our conversations, our self-evident choice: José Luis Salinas! Within academic realism, he keeps the throne. In that respect, Salinas managed to surpass even his greatest role model in creating comics, Hal Foster.

It’s not only about galloping… Getting on the horse, taking a horse into gallop, stopping the horse, getting off the horse – they are all phases and movements that Salinas turns into magic. Horses Diablo and Loco of Cisco and Pancho, of course, play a major but not exclusive role. Salinas moves viewpoint smoothly bringing different camera angles into counterpoints. The sense of time flow is crucial for the encapsulation, capturing prime moments in a story and a strong feeling for action and space. Salinas is powerful in rendering landscapes, capturing the depth of the scenes. And these panoramic scenes show his talent in full light. His interior design, on the contrary, is relatively scarce, often like a theatrical prop. In his introduction for the second volume of The Cisco Kid, Don McGregor perfectly pointed out the best panoramic scenes--the cinemascope single panels. In the first volume there are seven of these amazing wide-screen scenes. In the second volume we find six of them. In the third volume only one, and in this [the fourth] volume they regrettably disappear. We can only speculate why the frequency of Salinas’ usage of this powerful tool of his expression declined in time. Probably King Features editors asked him to do so, fearing that such a daily installment does not function properly in the perception of the daily reader - one single panel demands a stronger reader focus on the entire sequence that expands on the day before and leads into the day after, particularly if there was not much dialog in that single panel.

As Ricardo Villagrán mentioned in volume three, when reading The Cisco Kid, you cannot help but notice figure movements, even when they are in backgrounds. Salinas is a master of background movements. Even small movements, a turning of the body or just the turning heads of horses are enchanting. They never go unnoticed for the true connoisseurs and the readers who enjoy Salinas’ visual storytelling. We are constantly being pulled into the art and Cisco’s iconic poses remain engraved in the readers memory. As if there are two parallel stories: the genre story and the body language story of all the living creatures in this comic, a combination of story and visual narration. The Cisco Kid is not remembered for the stories but because of the authentic genius of Salinas. His visual narration goes far beyond the boundaries of the story. Within the dimension of visual narration he creates an unforgettable Western epic.

Restoration requirements

The Cisco Kid is one of the comic strips that requires restoration more than others. Why? Because there is a tremendous subtlety in Salinas’ line, his textures and decorative components. When we look at his art, we see needlework, embroidery. His pen stroke is precisely defined, almost a filigree work, a delicate kind of jewelry metalwork, usually of gold and silver, made with tiny beads or twisted threads, or both in combination, soldered together or to the surface of an object... metaphors aside, Salinas’ line work goes side-by-side with the precision of his teacher Hal Foster’s work. Unfortunately, the sources for reprinting The Cisco Kid are in much worse shape than Prince Valiant which was lucky to undergo multiple independent restorations: two color restorations and black and white. The color restorations were done by Fantagraphics and German publisher Bocola Verlag. The black and white restoration, Manuel Caldas. All three of them are impressive undertakings.

I admire Manuel Caldas’ perfectionism. I was directly responsible for connecting Caldas with Serbian publisher Makondo convincing them to publish a complete run of the restored Lance in four books (I wrote the introductions for each volume). But, my admiration refers to Caldas’ accomplished results, while one is not in a position to wait for his long and painstaking restoration process.

To wait for a full restauration by Manuel Caldas would be a mission impossible from the perspective of publishing all eight volumes, which is how many the Classic Comics Press has projected to produce a complete run of The Cisco Kid dailies. Up to now Caldas has produced one single volume of The Cisco Kid that covers only one third of the content of the first volume of the Classic Comics Press series. With such slow progress, it could take several decades to complete the total run!

Classic Comics Press is finding the best material within a reasonable period of time. Caldas' approach is perfectionism that ignores a question of time. Time is not important, only a beautiful result is important. On the other side of the spectrum, Classic Comics Press’ restoration and the scope of the entire venture are more than impressive. Their planned eight volume series is covering the entire run of The Cisco Kid, eighteen years, sixty-six adventures, a project of about nineteen-hundred pages.

Dreams & regrets: The Cisco Kid Sunday pages

How is it possible that Salinas’ artwork on The Cisco Kid has not merited him the status and fame of other top ranked comic artists, asks Dennis Wilcutt in his piece for the first volume of The Cisco Kid. Rod Reed put almost the same question… Don McGregor as well. All three of them agree that the reason may be in a never realized idea of Salinas creating a Cisco Kid Sunday page.

We can try to find the answer by analyzing some of his previous comics created in page format, easily accessible to be seen and read. I had opportunity to read and analyze the entire comic adaptation of The Three Musketeers. It was also possible to make comparisons with available samples from some other Salinas classic novel adaptations. For the purpose of analysis that follows, I will take it as a relatively solid ground for certain generalizations.

Scenes in The Three Musketeers are not closely related to each other. They are picturesque scenes in the tradition of the best in book illustration, but much more dynamic. However, they are more like a group of illustrations without having a compositional unity. Layouts of the page do not make a film-like sequence of action. Salinas makes a perfect composition of individual panels. Many of these scenes are dynamic. He uses beautiful camera angles, both low-angle and high-angle shots with hardly any close-ups. So it is partly engaging, partly distancing the reader from the story. Salinas constantly uses an angular overlap of the panels. Neither angular panel edges nor the presence of the speech balloons substantially affect the composition of illustrations. The scenes do not link fluently to each other. They are dynamic illustrations without particular page unity. Panels are not much subordinated to the primacy either of the sequence or of the page.

My analysis of The Three Musketeers is primarily applicable to Capitàn Tormenta, Miguel Strogoff, La Pimpinela Escarlata, and the astonishingly beautiful El libro de las selvas vírgenes (The Jungle Book). In El último de los Mohicanos (The Last of the Mohicans), on few pages that I had opportunity to see, there is more attention to page unity and sequentiality of action. As Charles Pelto mentioned in his essay in the second volume of The Cisco Kid, for these adaptations of literary classics, Salinas would first do the artwork, then would send the originals to a literary critic José de España, who was responsible for adding the text to these comic adaptations.

In Hernán el Corsario Salinas uses incomparably more sequential unity of action and some quite impressive half-page compositional unity as well (obviously production circumstances varied). However, there is still some distance to go to reach the masterful heights of the page composition that we find in Prince Valiant or Lance.

Those who regret that Salinas never made it to the Sunday pages are condemned to a domain of hypothesis. We do not know how Salinas would apply his talents to the layout of the Sunday page. From his previous comics, even from the first phase of Hernán el Corsario done on a bigger format, we cannot make conclusions with full certainty. Regarding color, we have his illustrative work and a few one-page comics with captions done in full color. That wouldn’t be enough to apply to a long run of Sunday pages. We do not know how the option of a color Sunday would function in Salinas’ hands. Would there be a near equivalent of mesmerizing colors of Prince Valiant or Lance? We do not know. What we know for certain is that there would be much more panoramic scenes in which Salinas triumphs, more scenes with a deep background and perspective. In its own terms, it would be a visual narration masterpiece.

[A version of this piece appeared in The Cisco Kid, Volume 4, Classic Comics Press 2018.]