Aarthi Parthasarathy is an artist, filmmaker, and writer based in Bangalore, India. She is the artist behind the internet sensation Royal Existentials, a webcomic. I met Parthasarathy at this year’s Fumetto International Comics Festival where she presented about the work of Kadak, a South Asian female artist collective which she is a member of, and her research on the history of Indian comics focusing on the representation of women and underappreciated women artists. It was an enlightening experience.

Beginning & Royal Existentials

Kim Jooha: How did you get into comics?

Aarthi Parthasarathy: I love comics and graphic novels, always have. I spend inordinate amounts of time and money reading them, reading about them. My elder brother used to read them, and those were some of the first books I read. In India, Amar Chitra Katha is a huge series that tells mythological and historical Indian stories through comics - and my parents encouraged me to read them. They were the gateway drug to other comics.

What are your favorite comics? Or your influences?

There are way too many to name. Way too many.

I started with the classics - Hergé, Goscinny, Bill Watterson - but I really love all kinds of comics. I really don’t know how to answer this question. It would be an overwhelmingly long list, and I would feel bad about not including something/someone in case I forget them. Everyone from Kate Beaton to Orijit Sen.

Were you trained as an artist?

I went to Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, where I studied communication design, with a major in filmmaking, and also graphic design with a big dose of writing. But I thought that my drawing was not as good as many others - I was more drawn to writing, photography and collage. I draw mostly for storyboards for our film work.

Could you tell us more about your film studio, Falana Films?

Falana Films was co-founded by me and my colleague and partner, Chaitanya Krishnan. At the studio, we do a mix of client and personal work. It is also how I try to make money, because in India comics is small and there’s not too much money in it. Maybe I haven’t understood the business of it. We work on client projects, and we do self-initiated short films - a lot of animated memes, small comics, illustrations, writing - the studio is a space for people to experiment, to do whatever they want. There’s also a metal and wood workshop, and a 3D-printing space in there. We ask people to use the space to create, make things!

How did you start making comics?

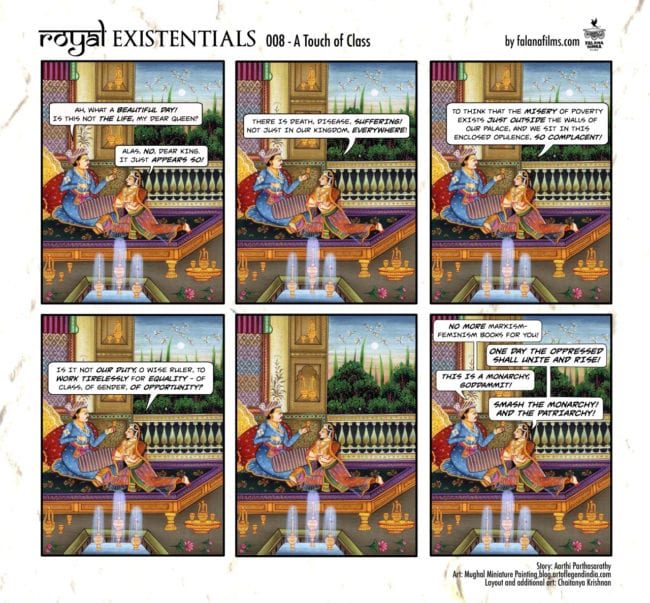

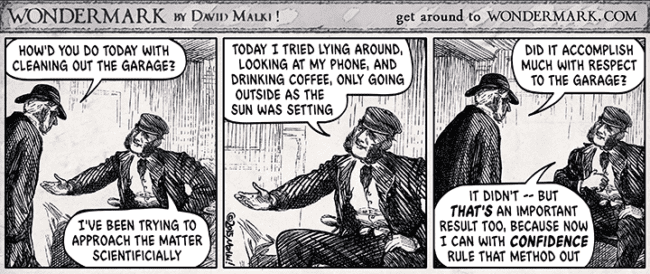

I always wanted to write them - I am not really a comic artist. The idea for Royal Existentials came to me about seven years ago, when I first read David Malki's Wondermark. It’s an American webcomic that uses Victorian-era illustrations, and he was using collage and appropriation in such interesting ways to make these hilarious, often political and socially sharp comics. I kept telling people that someone should do an Indian version. A few months later, I tried making one, which people seemed to enjoy. Then I just kept making them.

Royal Existentials was the first comic I worked on. It was just out of interest, and then I kept it going because I started enjoying myself. I had an interest in Indian art history, and I was studying some books to know more, that’s how I had some scans with me. Taking inspiration from Wondermark, I started playing with these images.

Royal Existentials was highly popular and influential. Did you expect that? What was your reaction?

It was surprising; I did not expect it at all. I didn’t expect it to be seen outside my circle of friends. The comic was a way to discuss what was happening in India, but the writing came from a much broader lens - the language is quite wordy and old-fashioned, the events are written about in a way that could apply to any region. The intent was to respond to the image - these kings, queens, servants, going about their business in these opulent palaces, speaking about democracy and revolution in a way that it creates an interesting paradox. The imagery from these times was the inspiration, and it came from engaging with them.

Why did you end it?

I had a health issue and required a major surgery. So I realized it was time to take a break. When I got back to work a few months later, I decided to concentrate on the studio and work on the projects there. Personal projects have been picking up slowly in the past couple of months, and I hope to pace better in the months to come.

Have you made other comics too?

Yes, I worked on a short series called UrbanLore with Kaveri Gopalakrishnan, and a few other comics with her, one of which ("The Same, Everywhere") was published in the book First Hand: Graphic Non-Fiction from India. I’ve collaborated with Aindri Chakraborty, Mira Malhotra, Renuka Rajiv, Chaitanya Krishnan on numerous comics -- most as part of the collective, Kadak. Other than that I work on film, animations and writing projects.

Kadak Collective

What is Kadak Collective? How did it start?

Kadak is a collective of women, non-binary, and queer artists who are talking about a gamut of social issues, mainly related to gender and sexuality, through graphic storytelling. So it is not just comics, but also illustration, graphic design, animation, and now hopefully other forms as well.

Kadak started in 2016. Eight of us came together to showcase our work at a table for ELCAF. Under the collective, we’ve got approximately forty self-published books/zines/comics in different formats. We showcase them in The Reading Room. There are webcomics too. We’ve done a few commissions for different publications/organizations as well, including Gaysi Zine (an Indian queer zine) and the Akshara Foundation (an NGO working with issues related to gender). Last year, we spoke about the direction the collective should take and we decided to take on a big publication project, and that’s where we’re at right now, with the Bystander anthology.

Why feminist and queer?

In India, the last decade has really brought a lot of issues into people’s consciousness - the issues of violence against women, representation, caste hierarchies, intersectionality, among others. Before 2016, when Kadak formed, there were a lot of incidents like violence against women and minorities that fired a well overdue outrage. There was the case of the rape of a young woman in Delhi in December 2012 that really shook the nation, and this led to big societal shifts in the way people talked about sexual assaults and toxic masculinity, embedded patriarchy in systems. We realized how the media had contributed to lopsided representations, encouraged misogyny, turned a blind eye to forces of caste and class hierarchy. A lot of us were wondering, asking ourselves, discussing, how we could contribute to this conversation? As artists, storytellers, we felt we had a responsibility. And as women, queer, non-binary individuals, we knew we were best equipped to tell our own stories. We believed there was a kind of storytelling that hadn’t been foregrounded, and we wanted to bring attention to it.

Feminist movements have been rising around the world in recent years. Do you think such international trends have influenced India or yourselves?

I think it’s a mix of both - with the internet, we were able to access larger, more global conversations, debates and ideas around feminism. And at the same time, there has always been a very powerful feminist movement at home in India. For example, there was an environmental resistance in India in the 1970s, called the Chipko movement, almost entirely led by rural women. Recently there was a big wave of #MeToo in India, with many women and minorities across the board coming forward with their stories, calling out men in the film industry, in the government, in the media, in religion, in universities - demanding action and accountability. I think a lot of these conversations have influenced us.

I’m from South Korea and my home country has seen the renewal of feminist movement recently too. Sad background fact: South Korea and Japan are two of the most misogynist countries among OECD/developed countries. I love this re-ignition of the feminist movement, but at the same time, there is a huge backlash, not surprisingly. I have received a threatening email “accusing” me of being a “femi-nazi.” When South Korean women protest on the feminist issue, they need to wear masks to hide their identity. It is the same for LGBTQ activism. So I was incredibly surprised by the braveness of Kadak: that you guys actually reveal your real names, publicly talk about these issues, and make art about it. Is there no such backlash? Is it safe to be open and out on feminist and queer issues in India?

There is a backlash against feminist voices - and the main reason is that people don’t understand anger. They don't know how to respond to it. Women and minorities have reasons to be angry, because entire systems have failed. So people don’t want to believe in these structures of law and justice anymore. One significant turning point in India was LoSHA. Raya Sarkar, who led this movement against a lack of action in incestuous circles of academia and the whole concept of due process, received a lot of criticism. Anything that seriously challenges the status quo suddenly and strongly will receive a backlash.

Folks within Kadak have experienced discrimination, and our work has been criticized, we've been called biased, "militant" even. Kadak itself has received comments: why women, why feminism, is it necessary, etc. People don't often understand why a space like this is relevant. We see a need for this kind of storytelling so we keep working together under the Kadak umbrella. We receive a lot more positive comments than negative, so that keeps us going. Though to be honest, most of us in Kadak are privileged. We create work mostly in English, and it travels only in certain circles. That's why we can work with our real names, and talk publicly.

I love the Unfolding the Saree zine so much. It shows the strength of Kadak of being more general graphic storytelling collective including graphic design, not just comics.

Unfolding the Saree is a zine designed by Mira Malhotra of Studio Kohl. It’s a beautiful zine, in the form and shape of a saree - on one side, it has a texture, one that you would associate with a saree, and on the other side, it tells the story of the saree - the history, politics, connotations of the garment, stories about it, its place in pop culture. The design of the zine is really eye-catching; it’s won a few awards!The idea for this zine came about when Mira was discussing making something about the garment, and all the different ways people look at it - which she spent a lot of time researching, and finally designed this zine.

You mentioned the Bystander anthology. What is it about?

The Bystander anthology is a very ambitious project — there’s a set of 51 South Asian and South Asian diaspora artists, who are contributing a set of pieces for a big print and web anthology on the theme of the bystander, someone who is present at an event but does not take part. Traditionally, the word has been used to connote inaction - an accident, for example, has a bunch of onlookers, who become bystanders because they do nothing to help. But someone could be a bystander because of so many reasons - because of fear, lack of access, disability, mental health issues, lack of power, etc. We wanted to unpack the ideas of inaction and action, because ‘what should one do?’ is the pertinent question now. We know so much now, because of the pervasiveness of social media and breaking news. But when someone doesn’t do something, or does something, is that right or wrong? How should one think about it? What about digital spaces? These are the questions we hope to address in this anthology. We’re crowdfunding for it, so we need all the help and support anybody reading this can extend.

I was impressed by the diversity of participating artists. The anthology features artists from not only several South Asian countries (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan) but also the South Asian diaspora (USA, UK, Canada, Germany, Netherlands, and Australia). Also it is not comics-specific. It includes architects, poets, and performers, etc. What was the curation process like?

Our initial wishlist was over 100 creatives. We spent a lot of time trying to include as many as people as possible. In fact, we’ve left a lot of amazing people out, which we truly regret. From the initial wishlist, the editorial team worked together over many weeks to arrive at a second list. Keeping diversity and representation in mind, we looked at artists - individuals and collectives - from different countries, identities, languages, abilities, kinds of work, and we arrived at 51 people.

Is the inclusion of other South Asian countries and diaspora common in other Indian/South Asian cultural projects?

Exchanges have always happened - in art, music, film, performance. In that sense, this approach is not new. It is definitely the first time it’s being attempted at this scale in the field of comics.

I have never seen such a case in comics. It pleasantly surprised me. How and why did you guys decide to include all of them?

South Asia is a large geographic entity, almost as big as Europe. Culturally, these nations have had a lot of exchange, and have a common thread of history. There are a lot of artists and creators who are making amazing, beautiful work; and are responding to political and social issues and events through timely and poignant pieces. We all follow each others work, but we felt there was a need to bring it together, in one single project. So we reached out to artists across the subcontinent.

Many regions in South Asia have had a history of conflict, which has led to migration and displacement over the years. We spoke about conflicts in India, in Sri Lanka, in Kashmir, in Pakistan - and there was a very clear decision at the outset about including all these identities as well.

Indian Comics History Research & Archiving

Your presentation at Fumetto was amazing. How much of it was your research?

Thank you! A fair amount of the images and comics, more than half of them, are from personal collection from Arun Prasad, a fellow enthusiast and researcher who has an astounding archive of comics. The others are from physical and digital archives, and from contemporary comic artists. The accompanying observations and stories are the outcome of our collaborative work.

How and why did you start working on the history of Indian comics?

I was interested in women comic artists, and I found a bunch of articles about many, many amazing women who made comics that I had never heard of. I came across Pretty in Ink by Trina Robbins, which documented and showcased many women artists in North America. Then I started reading up on women in comics in India - which led me to talking to Arun. We then decided to collaborate and work on a larger project on Indian comics history.

What is your goal?

We are writing a book. We don’t know how long it will take, but it is again an ambitious project. We are also taking the first steps in work on preservation and restoration of old comics in India - hopefully set up a comic museum at some point. This is a distant dream, but a necessary one.

Are there any comics archives in India?

There is no comic museum in India yet. There are historical archives, but they are libraries that include all kinds of books, magazines, and periodicals. There isn’t an archive with a focused study/inquiry on the medium.

I consider India more than a country. Not only is its population large -- more than a billion -- its history is long and cultures are so diverse. There are even twenty-two official languages! Is it possible to write “a” history of Indian comics?

A singular history is not possible, you’re right. But that’s what the book hopes to do - serve as a pointer to many different kinds of histories of visual storytelling. There are so many kinds of visual narratives in India, and they’ve been studied, revived, re-imagined in many ways over the last few years. We hope to showcase these forms, and present the links in a unique way.

I am also interested in the history and historiography of comics, especially from feminist, lesbian/female queer, and transnational viewpoints, and one of the problems I always encounter is that there are so many artists and works that are not well known. I mentioned the diversity and the huge scale of writing a history of India because I cannot imagine how much material there would be. I’m wondering if you have had a similar experience?

There is so much material! There are so many men, women, and queer artists whose work is not known at all. It’s often because of language, region, access, distribution. Another issue we are facing is the lack of preservation and documentation of these works - we find them in not ideal conditions, torn, cut out, ripped; and then the process of finding the artist, the context, the story becomes difficult. Then within language - so many of these comics haven’t been translated into other languages yet; and some issues and subjects that they broach are so specific to that context in terms of time and region. It’s quite challenging in many aspects, it can get overwhelming.

How is your research project different than previous Indian comics history narratives? I assume that yours will provide more “balance,” such as mentioning under-appreciated women artists and showcasing diverse cultures and languages in Indian comics, as your presentation at Fumetto did.

Exactly - our research looks at women, queer, and marginalized artists and writers, and aims to foreground their work. We’re also looking at independent publications, zines, unpublished works. The focus of our work is the narrative we’re building - it is not just a research project in that sense, there’s a story.

I had no idea that Indian popular comics were so hugely influenced by North American superhero comics. It is especially interesting to me, because East Asian comics are hugely influenced by manga, and nobody knew about North American popular comics and superheroes until the recent Marvel movies.

Yes, Lee Falk’s Phantom was a (bizarrely) hugely successful series in India - Indrajal Comics started publishing them in 1964. Though the story had to be adapted for Indian audiences - for example, the Singh Brotherhood of Pirates in the series had to renamed ‘Singa,’ so as to not offend Indian readers. Superman, Batman, and Spider-Man were quite popular as well at that time. These comics led to the search for an interesting Indian superhero, which led to the creation of Bahadur by Indrajal in 1976, followed by characters like Nagraj and Super Commando Dhruv from Raj Comics. Manga became popular (in the mainstream sense) here only later - maybe in the last two decades.

Political cartoons are the other big expression of the comics language that I spoke about in my research. From the days of Punch in the UK, and the many regional (unofficial) versions in India to the recent surge of webcomics and memes online that lampoon the government and public affairs, the political cartoon has remained a popular format for satire and critique in India.

How can people read about your research?

Right now, we haven’t published anywhere yet. I’ve given this presentation a few times in India, and then at Fumetto. Now we’re buried in writing the book, so I guess people will have to wait for the book!

How is the Indian comics scene, especially the alternative one?

It’s big now! Especially with the Indie Comix Fest, which is now in seven cities in India, and zine fairs coming up all over the country. And it's growing every month.

In addition to the Bystander anthology and your ongoing research on Indian comics, do you have any ongoing or future projects related to comics?

I’m currently writing and developing two short comics, and working on two zines which have political themes. Between the Film Studio, Kadak Collective, and the Indian Comic Research Project, I really have to hunt for time to do everything I want.