Richard Corben, who died on Dec. 2, 2020, was, in the words of Bill Sienkiewicz, both a “great artist” and an “American original.” He was also a pioneering filmmaker, a great innovator in the use of color and one of the first American artists to establish himself in European comics; but he remained something of an outsider, a recluse who shunned the limelight despite his international acclaim. What admirers like Bill Sienkiewicz, Moebius, Will Eisner, Neal Adams and numerous others appreciated was his combination of storytelling mastery, an animated sense of movement and a uniquely realistic technique of color and rendering that set him apart from anyone else in the art form.

Richard Corben, who died on Dec. 2, 2020, was, in the words of Bill Sienkiewicz, both a “great artist” and an “American original.” He was also a pioneering filmmaker, a great innovator in the use of color and one of the first American artists to establish himself in European comics; but he remained something of an outsider, a recluse who shunned the limelight despite his international acclaim. What admirers like Bill Sienkiewicz, Moebius, Will Eisner, Neal Adams and numerous others appreciated was his combination of storytelling mastery, an animated sense of movement and a uniquely realistic technique of color and rendering that set him apart from anyone else in the art form.

Corben was born in Anderson, Missouri, in 1940. He moved to Sunflower, Kansas, as a child and immersed himself in comics and animation, going on to study art in Kansas City, where he met his wife, Dona. Following six months in the Army Reserves, in 1965, he joined the animation department of Calvin Communications, where he worked for the next nine years. His discovery of comic fanzines sparked his enthusiasm, and in 1968 his first published strip: “Monsters” appeared in Voice of Comicdom #8. Soon he was in great demand, appearing in titles like RBCC and Anomaly (where he first collaborated with writer Jan Strnad) and in Voice of Comicdom #16 and #17, in which he serialized his first masterpiece, the crunchingly violent Rowlf.

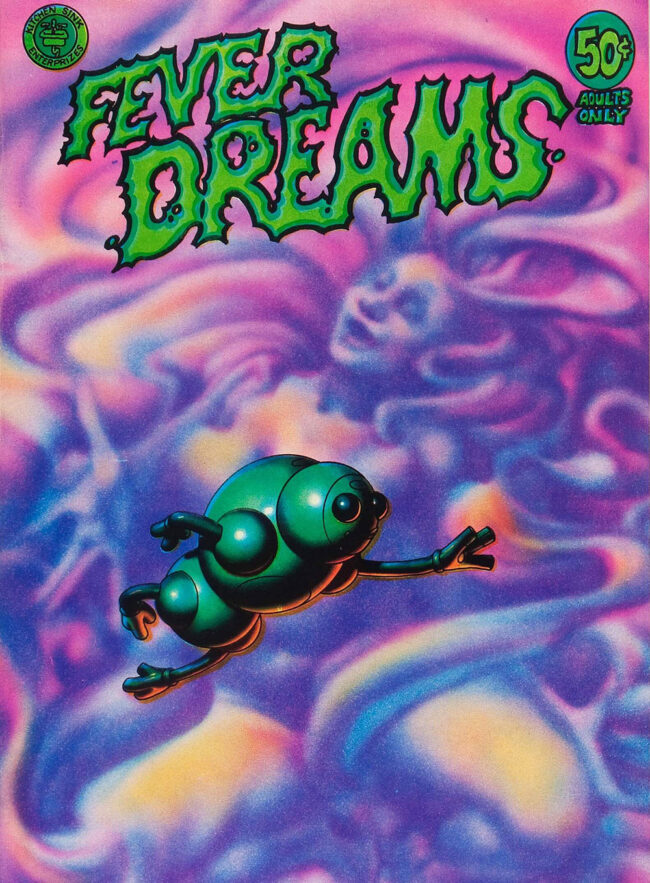

Corben’s next step was to save up and publish his own title, Fantagor, in 1970, which he largely wrote and drew himself — although selling the 1,000 copy print run proved to be harder than he imagined. Meanwhile, comic shop owner Garry Arlington was involved with Last Gasp publishing and in the creation of Skull Comics, an underground anthology rooted in the tradition of EC’s notoriously grisly 1950s horror comics. Recognizing Corben’s emerging talent, he sent the artist some copies of Skull and asked if he would like to contribute to its second issue. The idea that he might actually be paid for drawing comics, while still having the freedom to create whatever he wanted, was enormously appealing to Corben, who agreed to contribute. This first Skull Comics strip was followed by work in Slow Death #2, and Corben quickly began to amass an appreciative audience. Throughout 1971 and ’72, his work was published in more issues of Skull and Slow Death alongside such titles as Fever Dreams, Death Rattle, Anomaly, Weird Fantasies, Grim Wit and a revived Fantagor.

Corben’s next step was to save up and publish his own title, Fantagor, in 1970, which he largely wrote and drew himself — although selling the 1,000 copy print run proved to be harder than he imagined. Meanwhile, comic shop owner Garry Arlington was involved with Last Gasp publishing and in the creation of Skull Comics, an underground anthology rooted in the tradition of EC’s notoriously grisly 1950s horror comics. Recognizing Corben’s emerging talent, he sent the artist some copies of Skull and asked if he would like to contribute to its second issue. The idea that he might actually be paid for drawing comics, while still having the freedom to create whatever he wanted, was enormously appealing to Corben, who agreed to contribute. This first Skull Comics strip was followed by work in Slow Death #2, and Corben quickly began to amass an appreciative audience. Throughout 1971 and ’72, his work was published in more issues of Skull and Slow Death alongside such titles as Fever Dreams, Death Rattle, Anomaly, Weird Fantasies, Grim Wit and a revived Fantagor.

One particular highlight of this period was Kitchen Sink’s Up from the Deep, the first color underground comic, which featured the surprisingly poignant strip “Cidopey.” It was a showcase for a technique Corben had developed himself: using multiple sheets of color templates, often toned by airbrush, to create work of incredible luminescence and depth. Throughout the ‘60s, Corben had also created his own films, culminating in the fantasy-themed Neverwhere, a mixture of live-action and animation which impressed his employers at Calvin and went on to win a Japanese film festival award. For the second issue of Grim Wit in 1973, the artist revived Neverwhere’s concept of a bookish young American being transported to a fantasy world, where he was transformed into a naked Adonis, surrounded by pneumatic girls and bizarre creatures. It was not hard to see the strip, retitled Den, as a sort of adolescent wish-fulfillment: and these same themes of muscular adventure in fantastic worlds, coupled with unashamed sexuality, would typify much of his subsequent work. Some of his fellow underground creators, notably Bill Griffiths, felt he was essentially a mainstream artist taking advantage of the genre’s lack of censorship, but nonetheless, Corben felt buoyed by this first spell of success and finally quit his job at Calvin in 1973. Whereupon the underground market promptly collapsed.

Luckily, Corben had also been intermittently drawing strips for Jim Warren since late 1970, so turned his energies toward working for him in earnest, specifically on the 8-page colored strip inserts that had just begun appearing in his comic magazine titles Creepy, Eerie, and Vampirella. Drawing on his innovations in the undergrounds, the artist began to create astonishing images, both on his own work and as a colorist on Will Eisner’s legendary Spirit comic strip. Over the next six years at Warren, Corben established himself as one of the most exciting artists in America, culminating in several collaborations with writer Bruce Jones on strips such as “Within You… Without You” (in Eerie #77, #79 and “87) and “In Deep” (in Creepy #101) which remain career highlights.

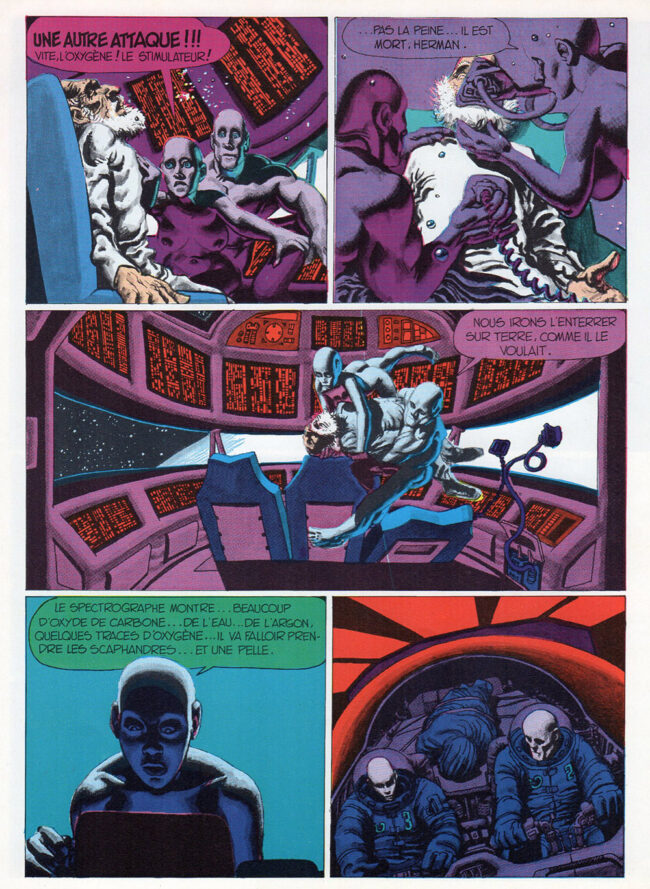

Meanwhile, in France, a revolutionary new comic magazine, Métal hurlant, was launched in 1975 by the Les Humanoïdes collective, which included artists Moebius and Druillet, and its first six issues all featured work by Corben, whom they had asked to participate. These strips were among his best colorwork from the undergrounds: “Cidopey”; “Going Home,” from Funnyworld #14, Den from Grim Wit and two new Den episodes, which revealed a remarkable artistic advance. Corben’s dystopian, sexual predilections made sense among the avant-garde science fiction strips of Métal hurlant, and over the next few years much of his work was collected into books by French publishers Futuropolis, Triton, Campus and Humanoïdes, and appeared in numerous issues of L’Echo des Savane’s Comics USA magazine. Alongside his Warren strips, Corben was also drawing an adaptation of Robert E. Howard’s Bloodstar for Morningstar Press, who subsequently commissioned him to complete the story of Den.

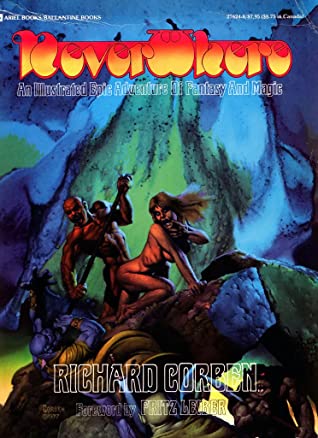

Squeezed in among his Warren commissions and a burgeoning career in book and record covers, work on Den took several years to complete, though he was spurred on by the emergence of Heavy Metal Magazine in 1977 from the publishers of National Lampoon. Heavy Metal was effectively an American version of Métal hurlant, comprised mostly of reprints from the French title but featuring the ongoing serialization of Den in its first 13 issues. Den remains Corben’s masterpiece, featuring exquisitely dynamic, realistic artwork of a kind that had never been seen in comics before. With sales of Heavy Metal at almost a quarter of a million copies each month, he was finally reaching a wide audience. In 1977, he also created by far his most widely seen piece of art when he was asked to paint the cover of Meatloaf’s first album; Bat Out of Hell, which went on to sell more than 43 million copies. It remains a profoundly iconic image and regularly features in lists of the greatest album art of all time.

Den’s success proved to be bittersweet; Morningstar’s graphic novel was released under their Ariel imprint as Neverwhere, but their contract with Corben ensured that they kept all profits from the strip for five years. This was particularly galling as the artist was now being represented by the Spanish agent Josep Toutain, who had so successfully introduced his Spanish artist to Jim Warren and was now selling Corben’s work throughout Europe. Most importantly, and radically, however, after Den, Corben worked completely autonomously, creating and owning his own work, which was then syndicated around the world by Toutain, making him, alongside Eisner, the first truly International American comic creator. His first project after Den was Mutant World, written by Jan Strnad, which was sold to Warren for his new 1984 comic, and published almost simultaneously in Toutain’s own Spanish version of 1984. Along with Den and his Warren collaborations with Bruce Jones, Mutant World shows Corben at the peak of his powers, with the artist reveling in the strip’s bleak post-apocalyptic milieu. For the next few years, much of his output was serialized first in Heavy Metal before being collected into graphic novels, starting with New Tales of the Arabian Nights (again written by Strnad) in 1978 and ’79. This was followed by newly colorized serializations of Rowlf, “The Beast from Wolfton” (From Grim Wit #1) and Bloodstar, the second adventure of Den; Muvovum, which ran from 1981 to 1983, and then, in 1985, The Bodyssey with writer Simon Revelstroke, his last Heavy Metal strip for many years. The 1981 feature-length animated Heavy Metal movie included a lengthy section based on Den, securing his position as one of the magazine's most visible artists.

Corben self-published the 1982 graphic novel Jeremy Brood under his own Fantagor imprint, along with an expanded collection of Mutant World, but subsequently, much of his work was released in graphic novels in the U.S by Toutain’s newly launched Catalan Communications. However, the emerging direct market for comics enticed the independently minded artist back into self-publishing, and from 1986 to 1994 almost all of his work was released by Fantagor. These comic and magazine miniseries were primarily sequels to his successful ’70s work, with Children of Fire (in 1987) and the 10-issue Den series (1988–89) subsequently repurposed as three more Den graphic novels. Other releases included Rip in Time with Bruce Jones (1986–87, inspired by their earlier “Within You… Without You” collaboration), Den Saga (1994) and a return to the horror work of his earliest undergrounds, with Horror in the Dark (1991) and From the Pit in 1994. The ‘80s was probably his most successful period internationally, with much of his work being reprinted across Europe, buoyed by the explosion of comic magazines and specialist shops. In Spain alone, all five Den books and a 13-volume career retrospective were kept in print until the collapse of Toutain’s publishing empire in the ‘90s, and these editions were widely translated across the continent.

But by the mid-‘90s, the Fantagor titles were increasingly out of step with prevailing trends of the speculator-led comic boom and the emergence of Image, so Corben began to look for work from elsewhere. Initially, he found commissions from Heavy Metal, now owned by Corben fan Kevin Eastman (whose Teenage Mutants Ninja Turtles comic he had drawn for in 1990), and then Omni and Penthouse comics. In 1996, he was asked by editor Mark Chiarello to contribute a strip to the Batman Black and White miniseries, which opened the door to more work in the mainstream. Beginning in 1997, he began a 20-year association with Dark Horse, initially working on the Alien Alchemy miniseries, which was followed by Conan, several horror series, and seven Hellboy stories in collaboration with creator Mike Mignola. This period also included numerous strips and series for DC, including work for Gangland, Flinch, Heartthrobs, The Spirit, House of Mystery, Hellblazer (issues 146–150 in 2000) and Swamp Thing (from 2004 to 2005). Most startlingly, he also found himself drawing such Marvel stalwarts as the Hulk (Banner #1-4 in 2001), Luke Cage (in 2002) and Ghost Rider (2006), as well as a series of Edgar Allan Poe and H.P. Lovecraft adaptations for Haunt of Horror (2006 and 2009).

Corben was, above all else, a unique voice in comics, whose work seemingly existed in its own universe; even when drawing other people’s creations, he somehow always made them his own. While he remained something of a cult figure in his later years, his standing in Europe as a major figure in comic art was never in doubt. This was confirmed in 2018 when he was awarded the Grand Prix at the Angoulême comics festival in France, followed by a career retrospective exhibition at the next year’s convention, which featured 250 pages of his original artwork. The two-volume catalog of this exhibition, limited to 1,500 copies, remains the only comprehensive volume dedicated to his career, though Fershid Bharucha’s 1981 book Flights into Fantasy is a fine introduction to his early years. Sadly, Corben was unable to attend the award ceremony. His death after heart surgery this December has brought forth a flood of appreciation and reminiscences from the comic world, emphasizing the enormous impact he has made over the years.

Corben was, above all else, a unique voice in comics, whose work seemingly existed in its own universe; even when drawing other people’s creations, he somehow always made them his own. While he remained something of a cult figure in his later years, his standing in Europe as a major figure in comic art was never in doubt. This was confirmed in 2018 when he was awarded the Grand Prix at the Angoulême comics festival in France, followed by a career retrospective exhibition at the next year’s convention, which featured 250 pages of his original artwork. The two-volume catalog of this exhibition, limited to 1,500 copies, remains the only comprehensive volume dedicated to his career, though Fershid Bharucha’s 1981 book Flights into Fantasy is a fine introduction to his early years. Sadly, Corben was unable to attend the award ceremony. His death after heart surgery this December has brought forth a flood of appreciation and reminiscences from the comic world, emphasizing the enormous impact he has made over the years.