Two volumes into Ed Piskor’s X-Men: Grand Design, the question still nags: who is this for? Usually these projects—your remakes, your reboots, your adaptations—are a siren call to the elusive New Comics Reader; the untapped market blithely sailing by, waiting to be lured into fandom. The moviegoers. Yet there’s an absence of asterisks here to carefully lead the curious consumer directly and permanently into the Marvel vaults. There are few notes in the margins for context, while the Additional Reading sections by Daron Jensen and Jeph York that serve as bibliographies in the single issues have been conspicuously excised from the paperbacks. Every indication is that Piskor clearly intends Grand Design to be a self-contained experience. So again: for who?

In an interview with Juxtapoz magazine, Piskor explains how he got into the X-business: “I drew some X-Men and sent out a tweet saying something like ‘Marvel should just let me make whatever kind of X-Men comic I feel like making.’ They got in touch within an hour and it was on.” It’s nearly unprecedented for a Marvel superhero project to be written, penciled, inked, and lettered by the same artist, as Piskor does with Grand Design, so it’s curious that—given creative control plus carte blanche to pick a project—Piskor chose to remake the first three decades of X-Men comics. “I assure you,” he tells Juxtapoz, “this was a comic that I've been building myself up 35 years to create.”

Why do a remake? Was the intention to take a kernel of the original and spin it off into surprising new directions—Piskor’s The Thing to Jack Kirby and Stan Lee’s The Thing from Another World? Would he reimagine the hallowed heroes from a contemporary point of view? Reinterpret the sacred text with the advantage of modern perspective? Or was this more about form than content? Should he recreate the X-Men from memory, the way Dirty Projectors did Black Flag’s Damaged on their album Rise Above? Switch the genre? The setting? The characters themselves? I have this secondhand David Mamet anecdote I’ll tell anyone who listens, where Mamet is arguing with a friend about Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, which Mamet had done a translation of, and his friend gets frustrated and yells, “Did you even read The Cherry Orchard, Dave?” And Mamet says, “They didn’t pay me to read it, Scott. They paid me to fix it.” Is Piskor trying to fix the X-Men? Or is this more like Gus Van Sant’s shot-for-shot redo of Psycho, just learning in public?

It skews the latter. Piskor does change plenty of narrative details from the original comics to fit his arc, but Grand Design often feels like it’s more about craft than story. Piskor is what you might call a student of the game (a phrase I’ve also used to describe his Comics Kayfabe co-host, Jim Rugg): he’s fascinated by how comics artists interconnect with, pay homage to, and cannibalize one another in their work—a trait the medium shares with Piskor’s other favorite subject, hip-hop. He’s constantly sneaking in visual references to other creators and redrawing images from the original Uncanny X-Men comics into different contexts. A battle lifted from issue #97, for example, is drawn to look like a fight from issue #100. The details matter to him. Piskor’s Silver Age-inspired coloring techniques, on which Mark Sobel’s TCJ review of Grand Design’s first volume goes into detail, make the books feel like a discovery from deep within the archives. Interviews with Piskor universally contain mention or pictures of his own library. This is a creator that not only cares what his work looks like, but how it fits into an artistic lineage. He’s imagining his own place in the history he’s rewriting.

When it comes to narrative, however, Piskor’s thoughtfulness feels misplaced. There’s a structural contradiction at the heart of Grand Design. Piskor wants the book to be, as he tells Juxtapoz, “a single, satisfying, tale with a beginning, middle, and ending.” But then he uses an episodic approach, with each page representing a single installment. Those are two very different modes of storytelling, with their own unique strengths and weaknesses that don’t necessarily play nicely with one another. Smashing together linear and episodic narratives, as Sobel points out, is essentially the Netflix model of television applied to comics. And like most Netflix series, Grand Design seems to be figuring itself out in real time. That means the reader doesn’t know where they’re at in the dramatic arc at any given moment, and the impact of individual events get lost as a result; pacing falls completely out of whack—a death match with the Shi’ar takes up the same amount of real estate as a sequence about answering the mansion’s doorbell; and transitions between pages are often jarring, disruptive of any attempt at a clean throughline.

Yet the conflicting desire for a single narrative also makes it so that we can’t take detours, get messy, or dwell on the emotional lives of the characters—all of which tend to make episodic storytelling thrive. It feels like Piskor is constantly hedging his bets on that single, satisfying tale; and maybe for good—or at least well-intentioned—reasons, if contradictory ones. For one thing, Piskor seems to love structural challenges. He does well with parameters. It shouldn’t surprise, then, that within the one giant architectural task of recreating the first thirty years of the X-Men, he’s incorporated fractal organizational challenges for himself throughout. But the other thing—the one that really disrupts Piskor’s desire for a “single, satisfying tale”—is that if you’re going to rewrite the X-Men story whole, you’re essentially rewriting Chris Claremont, and you’re going to have to grapple with the fact that Claremont is an absolute master of episodic storytelling. His entire tenure completely rebuffs the type of clean, Joseph Campell-type structure to which Piskor claims to aspire.

For my money, the best thing that Grand Design has done to date is the very first thing that it did: it reframes the X-men’s story as a philosophical showdown between Professor X and Magneto. The first volume spends a significant amount of time threading everything involving the inaugural class back to that conflict. This was Grand Design’s mission statement writ large: the idea that all the strands, the rebrands, the “wait, who’s on the team now?” decades, were all interconnected in a gratifying and resonant way. But this was just a subtly-remixed version of Claremont’s spin on the original creators’ work. Claremont spent much of his tenure fleshing out backstories—developing psychological arcs that motivate the action, and vice versa. In many ways, Grand Design simply takes Claremont’s numerous retcons and puts them into chronological order.

Claremont has a gift for reinterpreting events without rewriting them (see also Avengers Annual #10, which harrowingly recontextualizes Captain Marvel’s departure from the Avengers). But retcons are only one way that he capitalizes on the strengths of episodic storytelling. His work on the X-Men is intuitive and non-linear: he’s frequently jumpstarting issues in the middle of the action, crowbarring origin stories into characters’ real time traumatic events, or planting plot points that won’t pay off for years. The throughline is emotion, not action. It’s messy in the way the characters might themselves be experiencing the events. Some of the non-linear storytelling occurs for practical reasons, like the recapping of past events to give new readers a foothold in the narrative. But those recaps often have a Rashomon effect for longtime readers—each appearance gives shades of fresh insight and added context to familiar beats. As in real life, the present is always remixing the past.

Claremont also works non-linearly on a subtler level in the way he consistently tracks the X-Men’s interpersonal connections, and this is what elevates his run on the book into something special. He doesn’t necessarily create complex characters—rather, he gives each member of the team a simple internal conflict, sketched out in melodramatic strokes—but over time all the moving parts combine into a complex, dynamic machine. A reader can’t just track the story in terms of “A happens which causes B to happen which causes C to happen.” When “A” happens in Claremont’s X-Men, it affects each member of the group as an individual, each member’s relationship to every other individual member of the group, and each member’s relationship to the group as a whole. Then, when “B” happens, the effects ripple outward again. That’s a ton of information, and it requires a certain amount of emotional intelligence and emotional investment to follow it over a long period of time, especially because Claremont never dials down the complexity, he only ratchets it up.

To go back to the Netflix analogy, the Claremont of the late 70s/early 80s X-Men uses similar narrative devices to the ones that television began to use in the mid-80s and sparked three decades’ worth of storytelling growth and depth in that medium. In his 2006 book on pop culture, Everything Bad Is Good for You, Stephen Johnson calls the use of a complex structure that involves numerous plots happening at once “multiple threading”; the use of narrative signposts to acclimate the reader into the action at any given moment are “flashing arrows”; and groups of people with intricately entangled relationships are, ahem, “social networks”. Those mechanics tend to help episodic storytelling work and make make the epic storytelling of comics and prestige television both more demanding and more rewarding for audiences. Netflix series, while nominally episodic, count on binge viewing, which lends itself to the “one single, satisfying tale” model. They are quick to jettison multiple threading, flashing arrows, and social networks nearly altogether. So is Piskor. Compared to Claremont’s X-Men, Grand Design reads like a Wikipedia plot synopsis.

It’s no coincidence that the Dark Phoenix saga, widely recognized as Claremont’s apex, has a relatively simple throughline—Jean Grey gains absolute power, is corrupted—that develops through series of seemingly disparate movements, from the mundane (Jean Grey gets indoctrinated by the Hellfire Club) to the cosmic (Phoenix kills the population of an entire planet), all of which factor into Jean’s mental and physical deterioration. By the end of it, she has been manipulated, exploited, and condemned, all while having to reckon with her inner thirst for power and inability to control her body or mind—and as readers we are asked to experience all of that through not only Jean, but through each member of the X-Men. In Grand Design, Piskor sacrifices Claremont’s complexity for a contradictory sort of streamlined completism. He’s thorough when it comes to what happened and when, but he avoids digging into the messy emotional journey of the group, even thought that's the lifeblood of Claremont’s X-Men.

For example, one way that Claremont develops the reader’s emotional investment in his characters is by building downtime into the narrative so that we can experience both how the battles have affected the X-Men on a personal level and how the friendships within the group extend to the choices they make when fighting. The first time we see the X-Men playing pickup baseball, Claremont covers miles of ground in only a few pages, particularly with Wolverine, a mostly by-the-numbers tough guy to that point. The game creates tension between Logan and the group while revealing his deeper feelings for Jean Grey, which sets up for a later action moment where he’s forced to decide whether to save Cyclops, his romantic rival, from harm. It’s not exactly earth-shattering stuff, but those are the building blocks of good story. When baseball shows up in Grand Design, it’s initially delightful because there have been so few other diversions along the way. Then Piskor just uses the sequence to land a pretty obvious Nightcrawler joke.

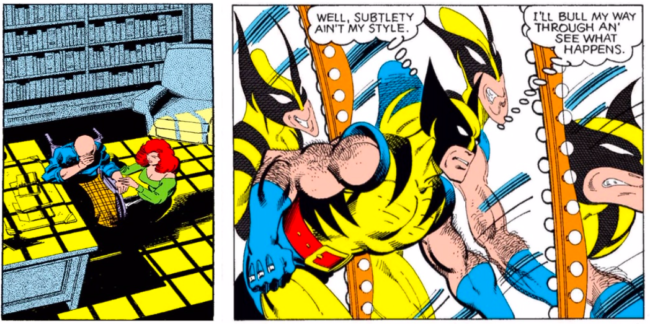

Grand Design consistently whiffs on these kinds of recognizable moments. Throughout the book, Piskor the writer seems to be counting on Piskor the artist to make up for his deficiencies. Claremont, of course, could do this; he had artists who supported and amplified his strengths. Dave Cockrum’s work from Giant-Size X-Men #1 through Uncanny X-Men #105, which typically gets short shrift compared to Claremont’s other collaborators, excels at a few key things that effectively helped relaunch the brand with Claremont at the helm. Cockrum’s drawing is less interested in being aesthetically pleasing than it is in being immersive. That’s the hook that gets you emotionally involved with the New X-Men before Claremont can give them psychological depth. Cockrum is consistently thoughtful about point-of-view: he likes to place the viewer at the point of impact, say, when someone gets thrown across the room.

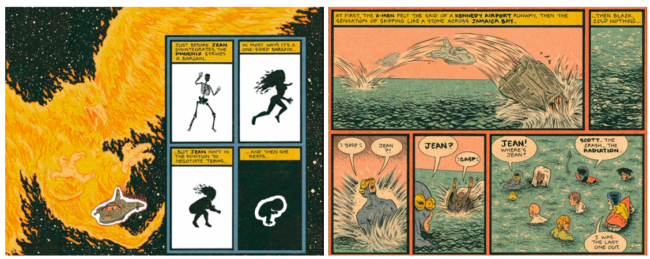

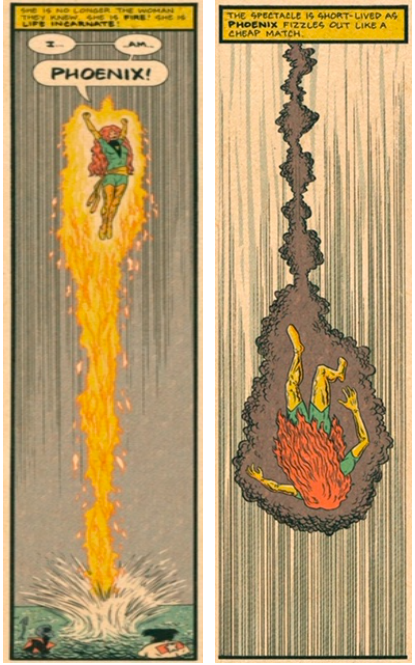

Compare his introduction of Phoenix to Piskor’s. In Uncanny X-Men #101. When the team crash-lands a space shuttle into the ocean, we experience it first psychologically, as Jean Grey struggles to telepathically hold the ship together; then we experience it physically, from the point-of-view of the water as the vessel rends apart mid-air. We are still half-submerged in the waves when Jean, transformed into the Phoenix for the first time, explodes out of the water.

Cockrum’s shuttle crash is noisy, chaotic. It doesn’t feel good to read; it feels like metal being ripped apart at the seams. In the opening panel of #110 (above left), the ship tears through Jean Grey’s head as she screams. Later, when she re-emerges from the wreckage, she erupts out of the water—transformed from a passive being into an aggressor. Piskor’s panels, on the other hand, mimic Cockrum’s while changing a few essential details. As opposed to a psychological onslaught, the energy that infests Jean is both literal and nonsensical: an actual bird made of… space flames? After the crash, he lifts our point of view above of the water, so you’re experiencing the tumult from a cold distance. Within two panels of a horrific ordeal, the X-Men look like they’re maxing out in an enormous jacuzzi rather than struggling to stay afloat in the hostile undertow.

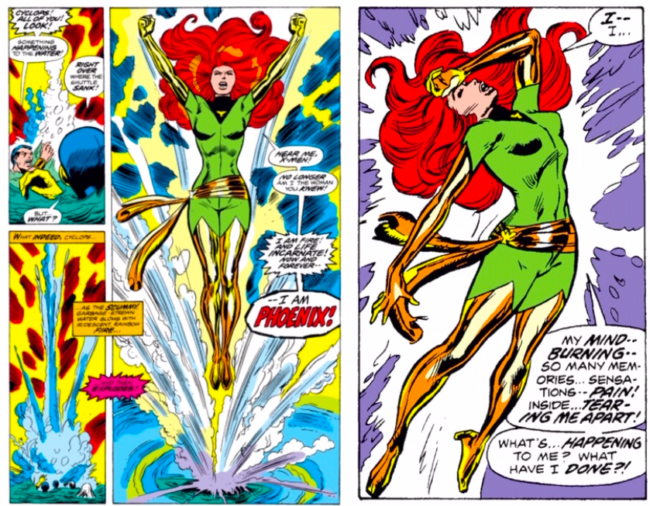

And that’s before we get to those iconic Phoenix panels. Cockrum and Claremont use a two-part build that sets the tone for the entire Dark Phoenix saga. The first panel shows Jean Gey's rebirth as the Phoenix. Cockrum shifts the reader’s point-of-view upward as the Phoenix triumphantly explodes from the water. We are at her level as she seems to consume the entire sky. In the next panel, she collapses. Awesome power immediately gives way to complete surrender. First, Jean Grey suddenly possesses infinite ability, but then the human body can only contain so much. Again, this is one of the simple dichotomies Claremont uses to define his characters, but Cockrum instills it with humanity. Note his positioning of Jean’s body. Now she is vast, open, limitless. Now she is broken, anguished, defeated.

Piskor handles this moment completely differently. He sets Jean at a tremendous distance from the viewer and angles her body away from us. In what is supposed to be an explosion of unforeseen power, she is dwarfed by the panel—smaller, even, than Nightcrawler and Wolverine watching from the water. Instead of thunderously declaring her rebirth, she appears to be feebly yelling up toward the atmosphere. The second panel is even worse, as Piskor obscures Jean’s face with her hair to make his analogy—that she has “fizzle[d] out like a cheap match”—work. The panels (and the analogy, for that matter), rob Jean of her emotional life in one of the character’s pivotal moments. Cockrum invites you into this intimate scene where Jean is at her most vulnerable; Piskor alienates you.

Cockrum’s talent for depicting the inner life of his characters reaches well beyond the birth of Phoenix. In his group shots, you can typically pick up on each character’s relationship to the rest of the team, even without context. In battles, you can easily track the logical push and pull of the action. Through Cockrum’s work, it’s easy to see a path that Piskor could have taken: one where his retelling of the X-Men story would stay economical, but with the emotional contours of the team coming out through the art. But that’s not where Piskor’s interests lay. He loves composition, but his mise-en-scène is rarely evocative. He positions the characters as if they’re action figures, guided by his unseen hand, bereft of any psychological motivation. He’s always thinking about how his panels look, but never what they’re supposed to be doing.

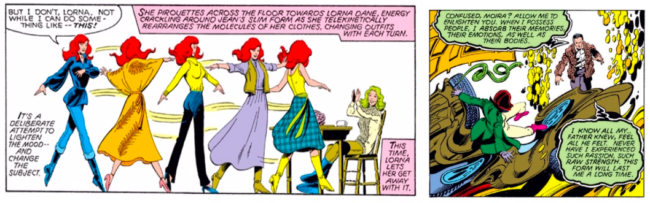

Piskor’s style has more in common with John Byrne, the other artist from the Dark Phoenix Saga—to whom Cockrum is often unfavorably compared. Once Byrne takes over, Claremont’s run on Uncanny X-Men starts jamming on a higher frequency, in no small part because Byrne’s work is so pleasing to the eye. His drawing may lack many of the experiential qualities of Cockrum’s work, but Byrne makes up for it by pulling from a seemingly inexhaustible wellspring of styles, including expressionism, surrealism, and psychedelia. At his best, Byrne elevates the series into something resonant yet unknowable. Professor Xavier’s depression is a cage of shadow and light; Jean Grey’s personality crisis is five outfit changes in a single twirl; Wolverine’s struggle with his worst impulses is the distortion of funhouse mirrors; and when Moira MacTaggert loses her son, reality becomes a slippery, abstract mess. Byrne doesn’t need to place the reader inside of the action the way Cockrum does because he bends the external world around the characters to reveal their inner lives.

It makes absolute sense that Piskor would want to make Byrne his primary reference point. Yet, for all Piskor’s comics literacy, he doesn’t have the vocabulary, the artistic range, or, frankly, the capacity for abstract thought that Byrne does. Where Byrne is endlessly inventive, Piskor repeats the same visual motifs across Grand Design, often without regard for what they’re meant to signify beyond the literal. His favorite trick seems to be using pure white color, since it stands out against the antiqued tan affectation of the pages. It’s a cool effect, but Piskor uses it incessantly and in ways that represent so many different things (psychic power, magnetism, ice, Angel’s wings, etc.) that when it’s meant to have its biggest impact in Second Genesis, the moment falls flat.

Continually, Piskor has a flair for the dramatic without understanding how to earn dramatic moments. And on their own, his panels are frequently clumsy or nonsensical. For a cerebral guy, Piskor reads as a severe under-thinker. Storm in “a claustrophobic panic” looks like she’s pleasantly dancing with a cellophane streamer; a volcano collapsing on top of the X-Men with “seismic intensity” looks more like a floating junkyard; in a fight scene, the team hilariously looks on with only mild concern as Magneto threatens to drop tons of metal on then; one panel where the team is supposed to be springing to action feels like an homage to clip art.

At the climax of the first part of the Phoenix saga, Jean pulls the X-Men into the M’kraan Crystal so that she can literally rebuild the universe. Piskor’s depiction of this high stakes moment presents everyone as paper dolls, floating against—his favorite signifier—a pure white background. The characters’ body language reveals absolutely nothing about the story. The panel could be plugged into dozens of places throughout the book and take on an entirely new meaning. The image is an homage to the X-Men’s battle with Dark Phoenix in Uncanny X-Men #136; if not for the presence of the Starjammers, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to suggest that Piskor had drawn it before he even knew where it would go. But look at Byrne’s panel compared to Piskor’s: it’s pulsing with energy and emotion, and you immediately get a sense of what’s happening, even without context.

Incidentally, Byrne’s depicts the M’kraan crystal event as a psychosomatic ordeal for the X-Men. In his very first issue, he’s already channeling the full range of his abilities.

It ultimately feels like Piskor either didn’t bother to figure out what makes Claremont’s X-Men so vital or doesn’t care—which circles back to the question of why he’s doing a remake in the first place. Piskor promotes himself as a longtime fan of the X-Men, but Grand Design reveals next to nothing about what it is that he truly likes about them. And where the creators of the most successful remakes—from The Thing to Rise Above—use their source material as vessels with which to explore contemporary themes, Piskor operates almost entirely on surface level (and he doesn’t always succeed there). Second Genesis does little to illuminate its subject on any level greater than simply filling in the backstory. It lacks insight and purpose, so much that it feels incongruous that he could be making Grand Design for actual fans of this era of X-Men. When the things that make the X-Men special—the broad-spectrum storytelling, the ever-evolving team dynamic, and the emotional complexity that grows out of that—are unavailable, what is there for readers at any stage of fandom to latch onto?

Could Grand Design be a repudiation of Claremont’s run, intentionally stripping it of its defining characteristics while keeping the most obvious signifiers? If so, maybe it holds up as some sort of feature-length pop art—X-Men qua X-Men. Piskor does seem to have a Warholian knack for self-promotion. In that sense, perhaps it’s not for X-men fans at all, but for Piskor fans. After all, branding is often about affiliation, and there’s almost no doubt that Piskor and Marvel aligned thinking they’d be great for each other’s PR. Grand Design is, if nothing else, Piskor Brand X.

Yet this would work against Piskor’s compulsion for referencing other artists. It’s difficult to completely reject a milieu while drawing inspiration from it. Add that to the list of other contradictions embodied by Grand Design, and you have a book completely at odds with itself. Piskor seems to undercut himself at every turn, which tends to be the mark of a creator who lacks a unifying vision—outside of the marketing department, at least. Look, that’s a common problem, and one that’s not always completely detrimental. But in this case, the whole project is about creating a unifying vision! So Piskor promises nothing if not coherence; he demands creative control, works in isolation, and eliminates direct ties to the source material, like asterisks and annotated bibliographies; and then he abdicates the responsibility to deliver on his one promise. That’s the failure of Grand Design: Piskor sells himself as an auteur, but he doesn’t really have anything to say.