There has been a real explosion in popularity for horror manga in western circles outside of the established horror-reading audience over the past decade or so, and their aesthetics continue to be more widely spread in online space in particular. While fans of the genre will be happy to see one of its less-celebrated-in-translation yet most talented creators, Hideshi Hino, published in English once again, this official translation of 1983’s The Town of Pigs, courtesy of Star Fruit Books, is also a release for those new or curious about the genre to keep an eye on - particularly those who might want an introduction to the work of one of horror manga's most unique creators.

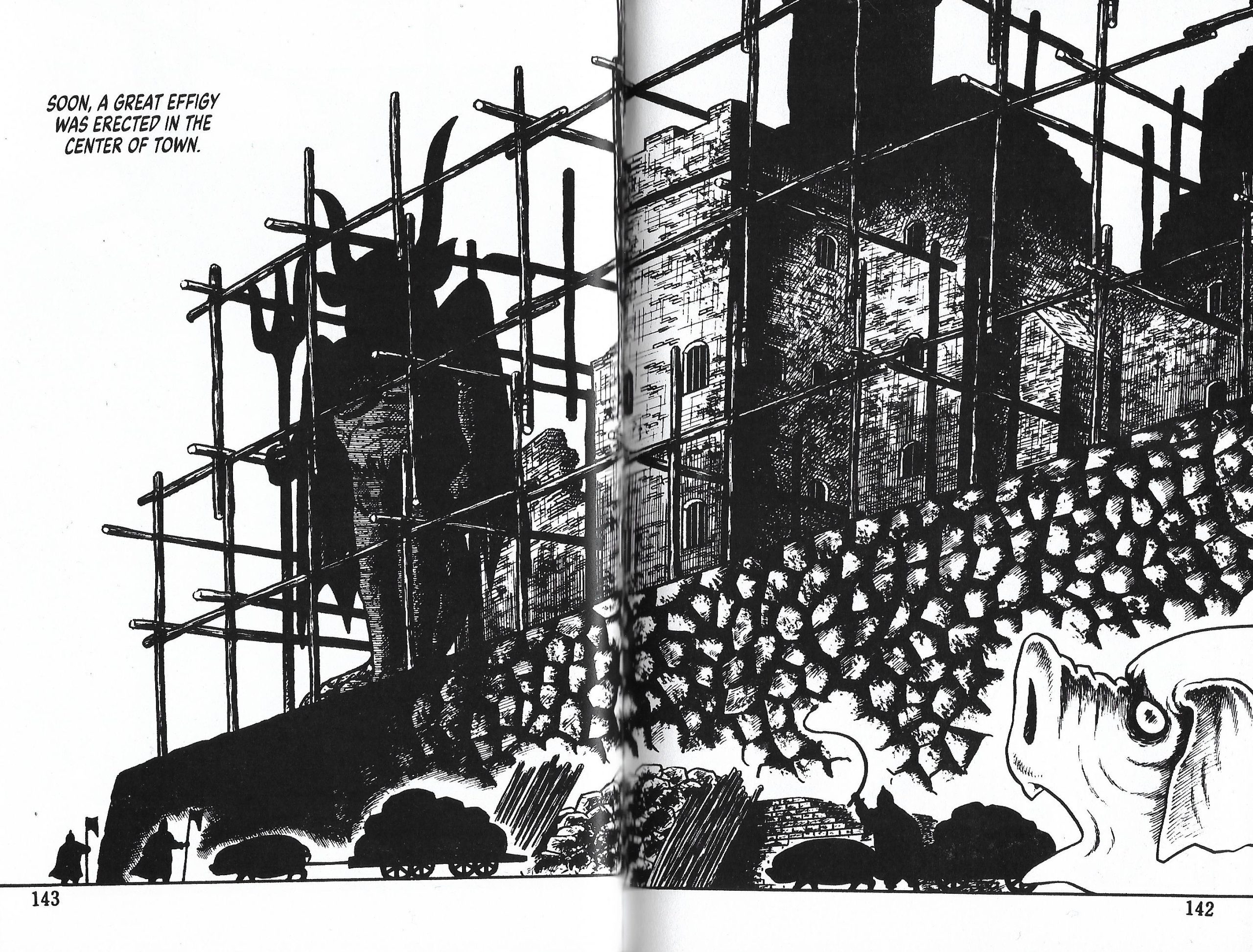

The comic follows young Kenichi, who wakes up one night to his small hometown being attacked by figures in dark robes, rounding up the townsfolk and razing the place to the ground. The boy narrowly manages to escape, spending the next few days trying to hide from the men in robes and making sense of the situation. The people of the town are brought back in shackles and physically transformed into grotesque-looking pigs; those who resist their captors are publicly executed. Though the premise is fairly straightforward as far as supernatural horror goes, what sets the manga apart from others of its time, and even more modern releases, is Hino's unique writing and artistic quirks.

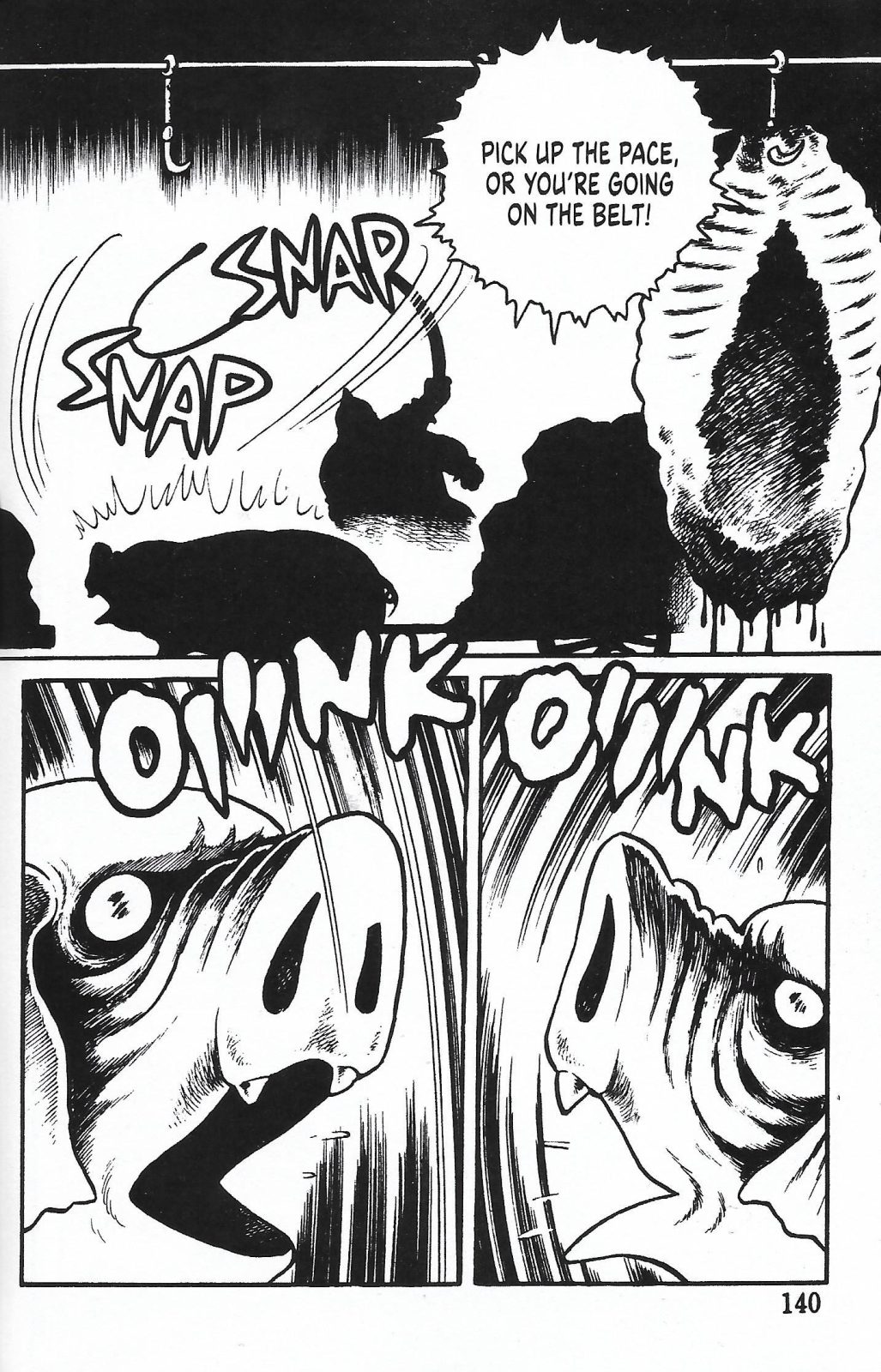

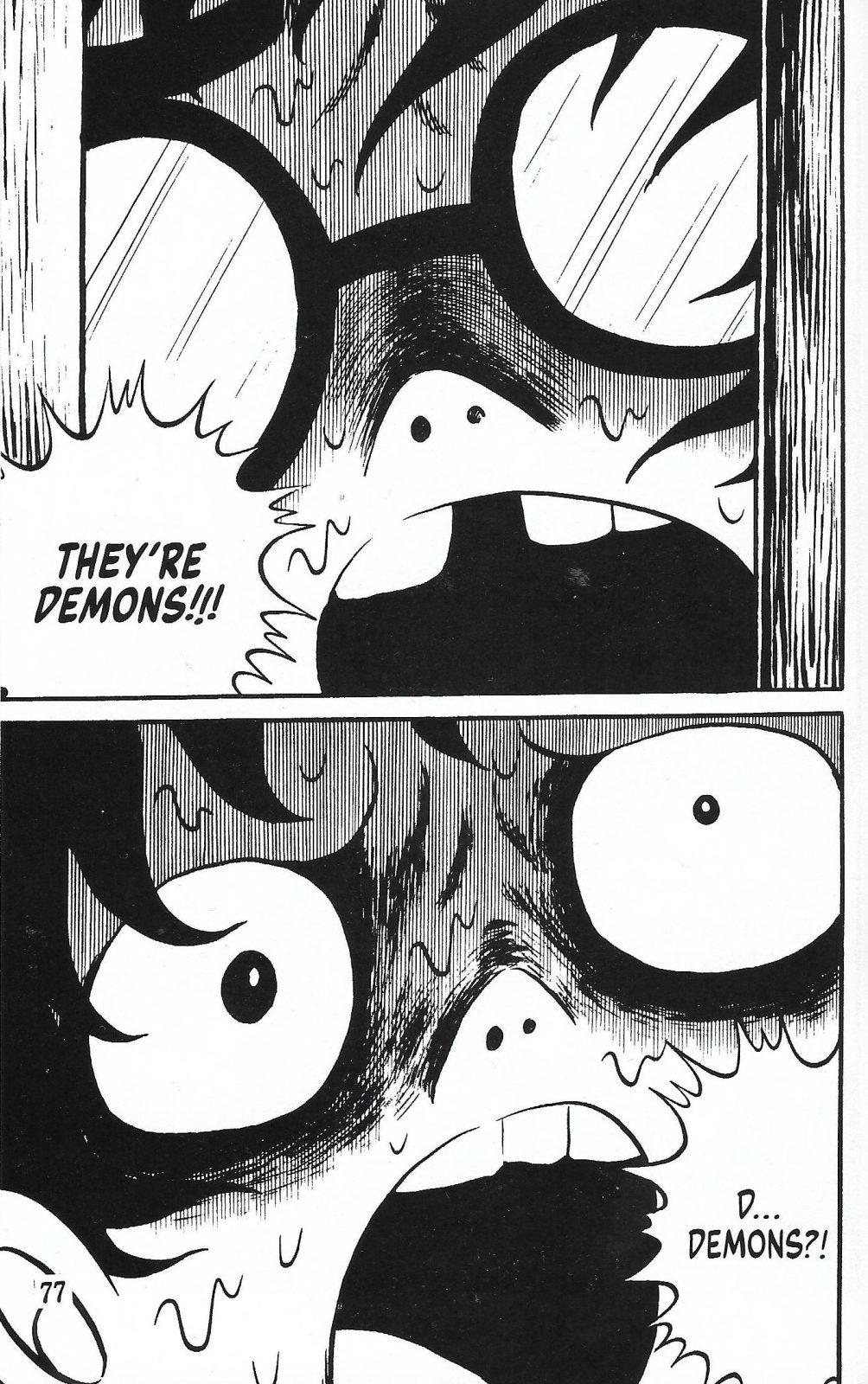

Whereas a trademark stylistic element of horror manga in the popular Junji Itō mold is to render everything in as much detail as possible–conveying as much visual information to the reader as the page will allow and thus creating a more believable and grotesque visual landscape–Hino accomplishes the same by taking the complete opposite route. Much like in Hino's other works, the art in The Town of Pigs is very minimal and almost cartoonish, with thick outlines and characters that have simplified designs and very exaggerated facial features and expressions. I’m pretty sure that the number of panels where the main character’s mouth isn’t open in a shocked expression can be counted on one hand, a sentiment I distinctly recall thinking back when I first read earlier translations of Hino's work, such as Hell Baby or Panorama of Hell.

Paradoxically, this doesn't mean that the art lacks in detail, due to the way the environments are illustrated using shadows and flat ink washes rather than empty page space. Though characters have simplified facial features and expressions that are almost permanently burned onto their faces, Hino gets the most out of them by playing with the density and placement of shadows; this applies to the environments as well, and gives the story a distinct visual style. Most of the manga takes place at night, depicted as heavy and oppressive, where the sky is pitch black and shadows indoors flood most of the panel space. Many times it feels like Hino draws less with outlines and more with the space in between pools of black, while also making use of heavy hatching to suggest detail in places without bringing them out into the light. Yet even the daylight feels oppressive and disorienting, such as when the boy’s town is torn down and rebuilt overnight - environments that should feel familiar are rendered completely alien to the point-of-view character, in turn reflecting the oppressive atmosphere of the world to the readers. It’s a very “ugly” story, stylistically speaking, yet intentional and stylized in its ugliness so as to avoid coming across as visually unappealing. Though it still goes for a grotesque aesthetic, this remains one of Hino’s least explicitly gory works.

While reading, I kept thinking back to the term “analog horror”, which gets thrown around a lot online to describe independent horror stories that ape the visual style of pre-digital media; while this isn’t accurate as a descriptor for this story, readers drawn to those aesthetics will nonetheless appreciate how, having been created in the '80s, the art in The Town of Pigs has that distinct grungy look that comes from being drawn directly in pen and ink rather than digitally. There’s something to be said about the slight imprecision of line and shape that can’t be easily replicated with modern digital art tools, which give artists far greater control over every line they put down on the page; these slight imperfections of traditional art are lost in a lot of modern manga, horror and otherwise.

The end result is an atmosphere that perfectly reflects the feeling of being trapped in a nightmare, particularly during the nighttime scenes. Just like in a dream, where it’s difficult to focus and make out details, readers are never given a complete picture of what exactly is happening or where the characters are, which is accentuated by the more personal touch of traditional art as opposed to the precision of digital.

In what’s common for Hino’s work, the story ends in a bizarre twist that I prefer not to spoil - not just to keep the surprise fresh for potential readers, but also because I’m still not entirely sure I fully “get” it. "Ahhh... that's right!" Kenichi exclaims, bringing the story to a close. "Suddenly, it all made sense!" Hino does not, however, explain what the character has realized, nor how his closing twist connects to the townspeople transforming into pigs. The ending could be seen as shocking, bizarre and unsettling, or just weird for the sake of weird, and I like to think I fall somewhere in between. While I appreciate the way the story uses its twist to bring the tone and stylistic choices seen throughout the story full circle—and I love the sense of sudden, violent estrangement from the main character that is created by having him attain an understanding that we, the readers, do not have—it is true that I was left slightly disappointed by the way the story builds up its central conceit and then seemingly forgets about it near the end. While it’s certainly not bad at all, and the themes and tone of the story are fully developed throughout, the actual narrative almost feels like the script to a different story got mixed in with this one somewhere along the line. Readers who expect tight, completely developed narratives might feel disappointed in the direction the story veers into towards the end.

Overall, I came away from The Town of Pigs mostly satisfied; though part of me wishes the narrative would be a little less aimless, I can’t help but love the way Hino uses his artistic sensibilities to create this hazy, almost dreamlike (or perhaps nightmarish) aesthetic. Like most of Hino’s work, this book is less interested in telling a complete narrative than exploring visual ideas tied together loosely by a central story hook. It’s less about events that take place, and more about conveying the feeling of being trapped in an incomprehensible, horrifying situation that can’t be fully understood, running on the kind of dream logic whereby the more that is revealed, the less sense everything makes. For fans of horror, in manga or otherwise, this is a great read as it provides a well-rounded portrayal of its niche, as well as a great introduction to Hino’s overall body of work, which is especially valuable to those already invested in the medium who might want a sample of one of its less-discussed creators in the west.