Childhood, as hardly needs to be explained at this point, is fraught with peril. Children’s literature has always presented the lives of its subjects in this way, and where it does not suffer from an artificially imposed blandness (or its opposite number, a deliberately and falsely cultivated darkness), it excels the most when it portrays the realities of an unpredictable world filtered through the perception of young minds that have not yet learned how to contextualize them. This is what the innocence of childhood is: the impressionable state of mind before both joy and suffering can be placed in the frame that surrounds them for adults.

The Nightingale That Never Sang is a collection of just such childhood stories by Juliana Hyrri, a Finnish cartoonist, painter, and illustrator. This is her first collected book, and it is a miraculous achievement, one of the most impressive works of comic art of the year. Its six tales are extraordinarily precise, cohesive, and expressive, with an artistic consistency that belies the wild variation in their moods, which are, after all, the mercurial moods of a young child. Having read them once, the reader is almost compelled to read them again, to see what magic their small but thunderous revelations have hidden.

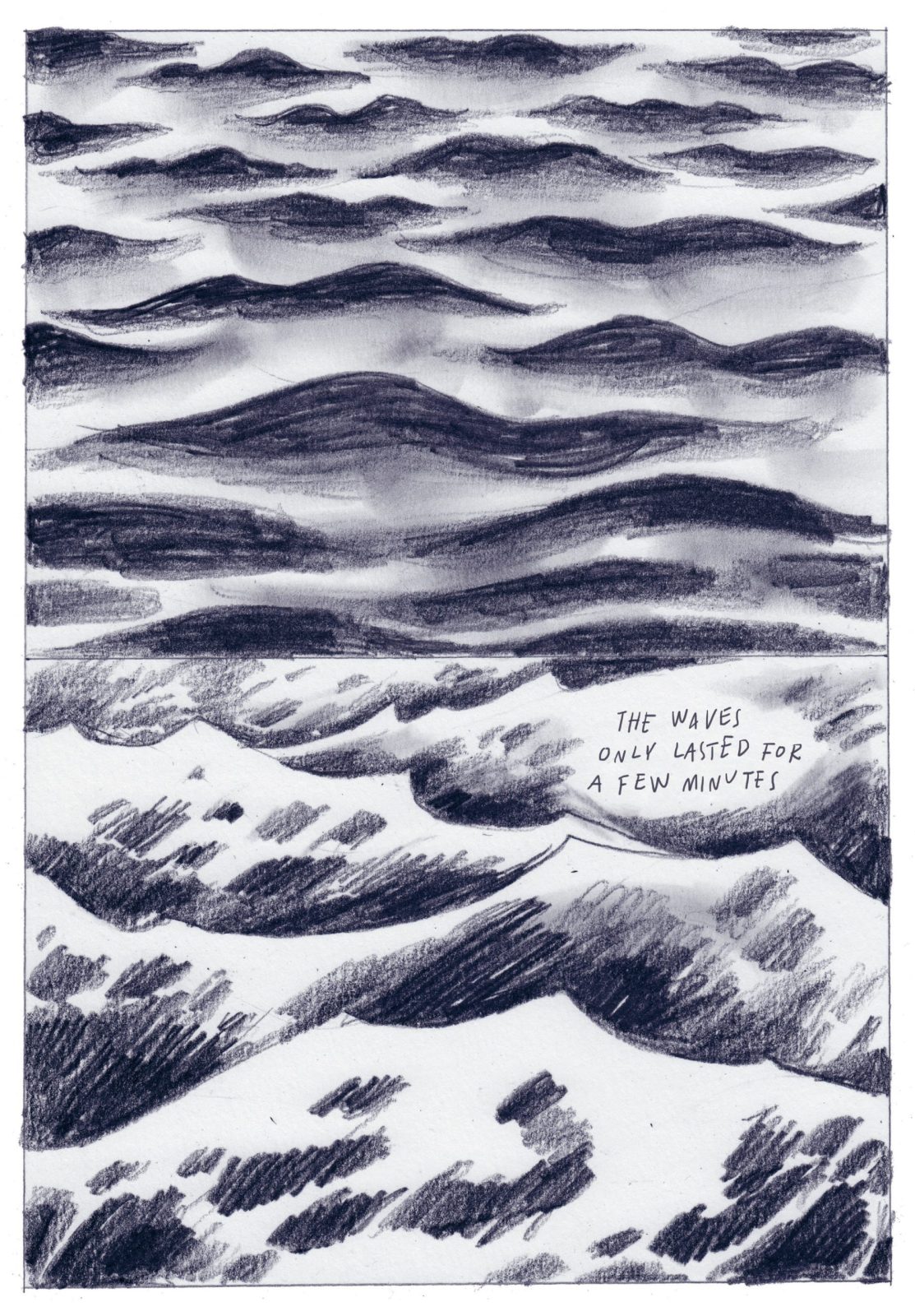

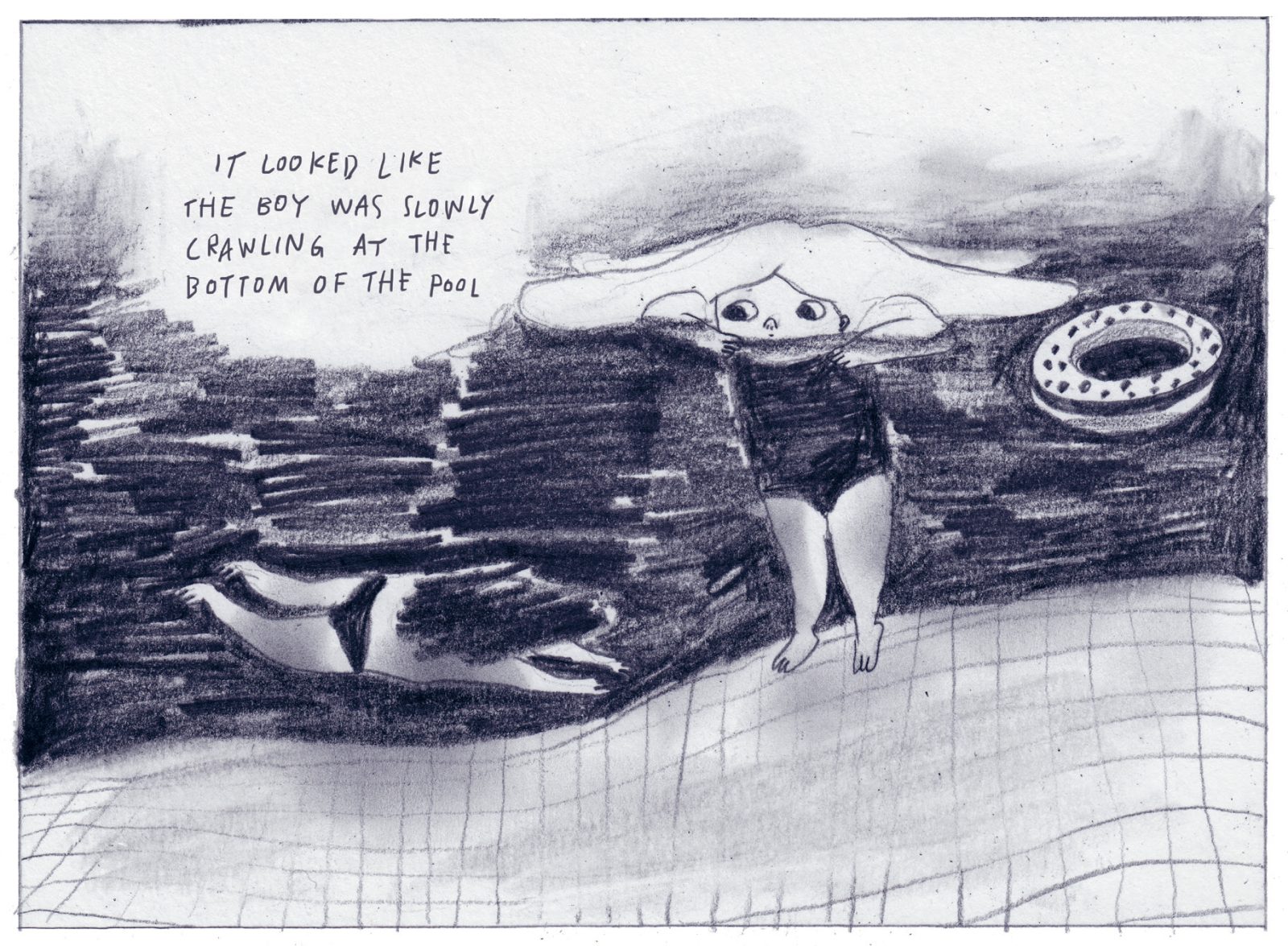

Hyrri’s drawing style is simple and effective, almost childlike itself with its distorted lines and rough shadings that creep over their edges. But the composition and arrangement is quietly sophisticated, with a natural elegance that belongs not just to childhood but to the nature itself - suitable for these stories where the delineation of the civilized adult world and the wild places of the natural world blur together like dreams at the edge of waking. They are mostly black and white with the occasional wash of pink watercolors, further placing them in that murky area of half-forgotten memories.

The first story, “The Blue Swimsuit” (written with Elina Johanna Ahonen), sets the tone for the entire book, beginning with a sweetly charming incident when Hyrri’s third-grade class takes a long-awaited trip to the water park. There are moments of comedy, innocent enjoyment, and the occasional missteps into the world of older children and adults that sometimes intrude on such times, until the waves assume the vastness and menace of a larger world. This is a forewarning of an event that immediately shocks the reader into chilly alertness, but which is read by the children in that context-free way we mistake for innocence.

“Wild Roses”, the first story washed in light pinks and dull oranges and off-reds, is perhaps the loveliest and purest example of the depth of childhood play: As Hyrri recalls a doll’s house she and her friends made out of cardboard and an old bedsheet, we are carried away by how adorable it all is, until she reminds us that the fantasies of children always contain darker elements than we can guess - or, more precisely, than we allow ourselves to remember. It ends with a jumble of broken and discarded toys, playthings that reflect guileless horrors in their dead plastic eyes.

The middle story, “The Sleepover”, is filled with such exhausting stretches of shifting mood and tone that it is almost too much to bear. Childhood sleepovers are so common, such classic fodder for adult remembrances of the odd emotional tenors of childhood that can never be fully recaptured, that it’s astonishing to see Hyrri bring such a fresh and intense interpretation to them, where a single movement or gesture carries such power for adults, who see them with such profound difference than they experienced as children. (If I am being frustratingly vague about what actually happens in these stories, it is absolutely intentional; Hyrri fills them with such strangeness and fright that I’d be ashamed of spoiling a single one of them.)

The story which gives the collection its name, “The Nightingale That Never Sang”, is a powerful evocation of the eerie, almost mystical hold that animals exert over children, before adulthood lets us put them at a cynical distance. It’s stunning in its ability to remind us of the ease with which we once encountered the natural world, as well as the unrealized cruelty with which we treat it before we really know what we’re doing. Like all of these stories, it ends with a simple sentence that seems completely uncalculated, but hits like a gut punch, putting the entire story in perfect emotional context.

“Being Selfish is a Sin”, too, deals with the magical connection between children and animals, the way it is so easily formed and so easily broken, as Hyrri takes in a stray cat that later gives birth to kittens inside her home. (The almost embarrassed expression she gives the mama cat when Hyrri discovers the litter is one of the most remarkable things I’ve seen in comics in ages.) It’s an amazingly deft blend of myth, ritual, memoir, domestic comedy, and awe, and perhaps the most moving story in the book.

The collection concludes with “The Clambox” (written with Myrtillus Kauria), in which two girls look at shells while Hyrri recalls a harrowing late-night conversation with her father (who, like most adults in the book, makes his presence strongly felt while never quite being present in the story). It’s a perfect conclusion, and a reminder of how much adults expect from–and need from–children who are incapable of yet understanding the depth and intensity of that need.

The stories in The Nightingale That Never Sang are among the best artistic evocations of an adult artist’s understanding of the events of childhood that I’ve ever encountered, beautifully and dangerously fusing the events as they are remembered with the meaning that was so elusive at the time. It’s an arresting and accomplished work that heralds the arrival of a major talent, a work that understands exactly what it is doing and never makes a misstep. And like the memories it brings to life, it allows us to look at the events it portrays in two ways: with the strange wonder of youth, and with the dreadful understanding of maturity.