The tragedy of the American comic book in the 20th century was its struggle for cultural recognition. Artists, writers, editors and publishers in this competitive, ultra-commercial market had to weather changes in public taste, to determine if a current fad would last long enough to invest in it (as with the 3-D comics boom of 1953) and to evade the radar of self-appointed censors and arbiters of “good taste”.

Any hope of creating quality work that would engage the public, open their coin purses and keep their efforts viable—especially in the post-war market, where shifts in public interest, condemnation of comics’ content and few avenues for honest distribution kept publishers scrambling—was quixotic at best. It seemed the comic book (unlike the newspaper comic strip) was a popcult form doomed to slake the appetites of America’s bottom-feeders; never its elite.

It’s a miracle that anyone tried to exceed the norms. It just wasn’t worth the heartache. Publishers, editors and writers flew blind. No demographics existed to help them; any intel they received was months old by the time it reached them. The major changes in subject matter post-war—romance, crime and horror comics—aimed at the sensation-seeking reader. Writers could give a damn about their plots and characters and attempt nuance in four colors; editors might hope their work did better than their rivals’. But most of it aimed low, because it was easier to do. It held more potential for profit. The more murders, violence and melodrama in a crime comic story, the better.

The EC (Entertaining Comics) line tried to deliver superior material within the genre frames of horror, science fiction, war and crime. They often succeeded, but publishers like Victor Fox, who did not care about quality, outsold the EC titles with crude, soulless upchuck. Some publishers (DC, Dell) self-policed their material and took pains to accentuate the inoffensive. Most looked at the work of their rivals, created their version of it and produced commercial material without sincerity or finesse.

The individuals who have provided cover-to-cover digital scans of mid-century comics—available for free on the Internet—have liberated this material from its now-forbidding status as untouchable investment items and shown us what these comics were about. Much of them are unreadable. The work is either too dull or so coarse that it takes effort not to disengage. But these scanners have also revealed creators who did give a damn and whose work stands out in stark relief: it has intelligence, and it conveys the personality of its maker. The canonical honor roll of names doesn’t need to be recited. Seeing these superior creators’ work side-by-side with careless, rote material done for low wages by uninspired artisans makes evident the essential truth of the mainstream comic book. If you wanted to put in all that hard work to do something good, you could. You got paid the same whether it was high art or crap.

Among publishers who did give a damn was Lev Gleason, whose Comic House imprint birthed the crime comic during World War II and whose titles offered more substantial—if static—reading than most of their competitors. Editor Charles Biro had a clear passion for his work, and, as EC’s Al Feldstein would do in the 1950s, felt that more words per page was part of the solution. As cartoonist and comics historian Michael T. Gilbert notes in this fascinating, revealing new archival reprint, a Biro comic has few if any captions. Its characters talk, talk, talk their way through exposition, character relationships, conflicts and challenges. It takes longer to read a Biro-edited comic that you might spend reading three DC super-hero issues or Timely-Atlas-Marvel’s genre comics of the same era.

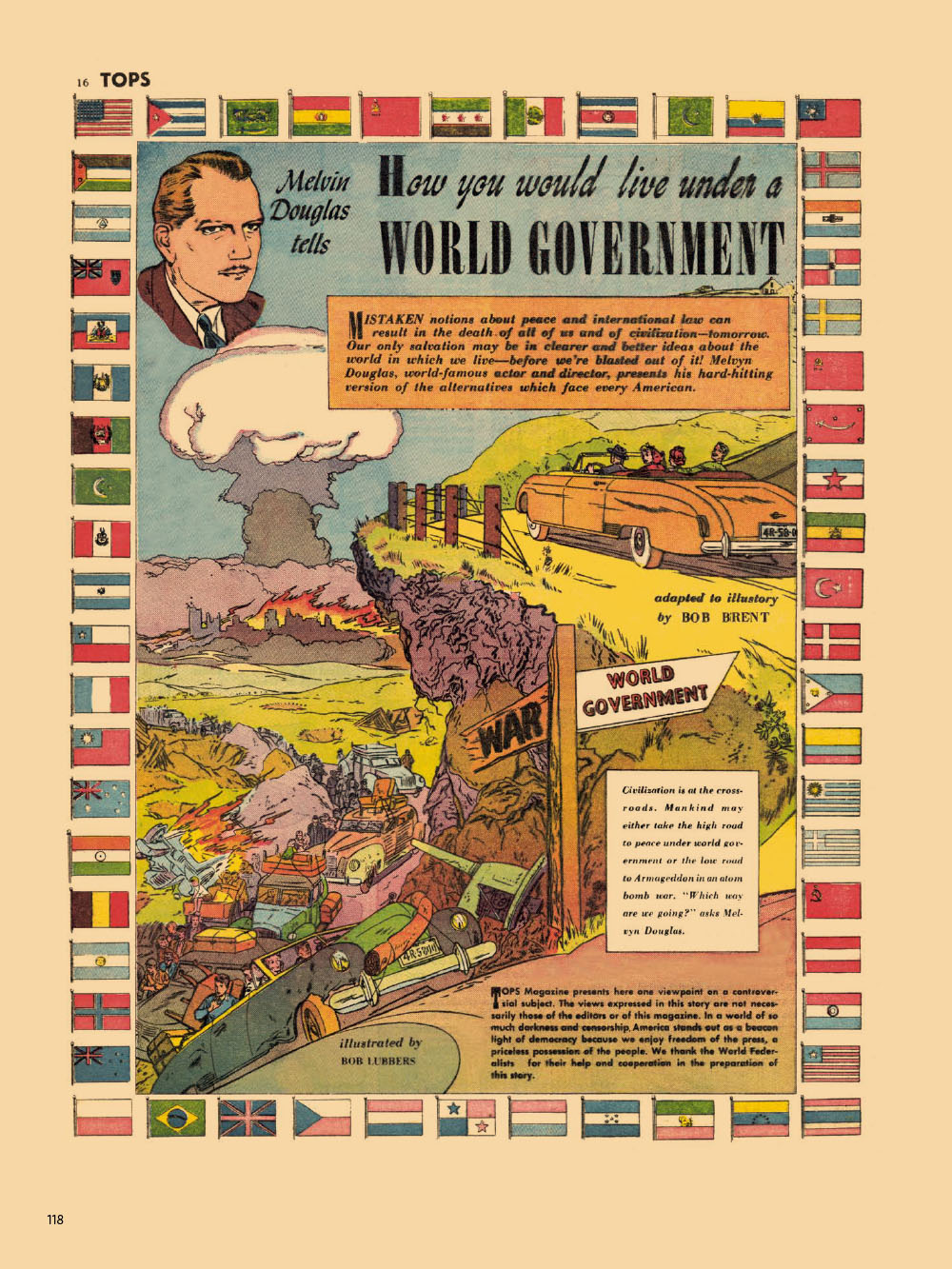

This philosophy is essential to Tops, the most ambitious failure of its day. Tops was conceived as reading for intelligent adults. Its two issues were the same size as Life, the weekly photo magazine. Biro hoped to have it printed on decent paper, but the bottom line prevailed. It was printed on the same acidic wood-pulp as the 10 cent comic books, with the same hold-your-breath printing quality. Biro invited the best artists in his rolodex to illustrate stories that range from serial-killer drama to biography to a treatise on why a world government would be best for us all, narrated by suave movie star Melvyn Douglas. If its two issues were done without data on what the adult market might prefer, it succeeded in producing stories that remain compelling and worth reading.

The story behind Tops, told in Gilbert’s revealing introduction, is interesting enough that, were the stories dull, it would still make this book worthwhile. Reading a comic book story of almost eight decades past, a 21st century spectator will find cavils—racism, sexism, etc. Weighed against those adverse expectations, much of the material in this large, handsome book stands the test of time.

You might feel discouraged if you read Bill Spicer’s “New Directions for the Graphic Story”, a 1967 essay on the two issues of Tops also included up front. Spicer’s take on this material might seem confounding. He approached these stories as they neared their second decade. Twenty years after their creation, few things look good. They remind us of whatever made us cringe about their recent time and seem to lose whatever subtleties they possess. Given more time, their assets or liabilities may seem easier to appreciate. I found Spicer’s essay of interest, but I’d have put it at the end of the book. I advise you against reading it before you approach the stories.

Another cultural anchor the book might have considered was the original paperback novel. These 25 cent softcovers filled newsstands as the two Tops came and went. As with comics, they were a recipe for hackwork, but allowed capable, distinct writers to find their voice and sustain it. The best of the paperback authors of 1949 remains readable and compelling. It’s the flavor of those novels that complements the contents of Tops—both were created within genre trappings but executed with care and intelligence.

The opening story, Charles Biro’s “The Closet,” illustrated with grace by Reed Crandall, typifies the Tops experience. We might think of other mass-market signposts of their times: Universal-International films noirs, Fawcett Gold Medal paperback originals, radio dramas. “The Closet” strives to be as good as, if not better than, those adult entertainments. Its story of a man whose embezzling scheme falls apart around him is heightened by its settings and its other characters. Crandall responded to this richer material and gave it a strong sense of time and place. None of its characters are glamorous, heroic or handsome. Crandall’s slick, solid approach is ideal for the subject matter.

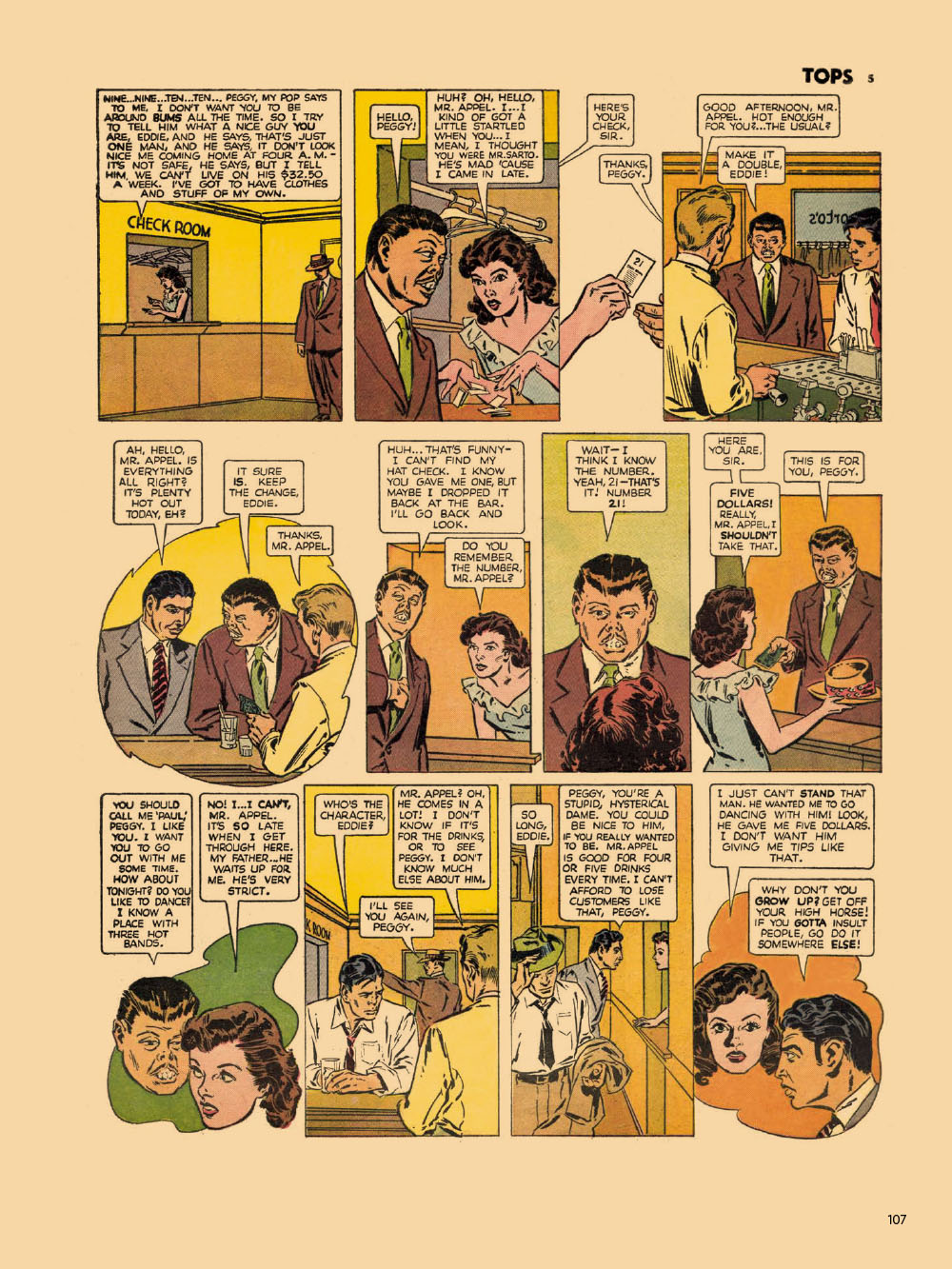

He bests this effort with issue two’s “Hat Check”, again written by Biro. This story is close to the spirit of mystery writer Cornell Woolrich’s jet-black worldview. A young woman from a poor family works a night job as cloak-room attendant at a New York nightclub. She doesn’t get along well with her parents and seems uncertain in the worldly atmosphere of the club.

When a recurring customer with a cleft palate and a disturbing demeanor fixates on the young woman, he fills her life with tension and unease. He stalks her as she walks alone, late at night. She demands he cease and desist, but he refuses. The newspapers report a serial killer on the loose, and she fears she’s been pulled into the orbit of a disturbed individual.

“Hat Check” succeeds in its wealth of atmosphere. As with “The Closet”, Biro and Crandall take pains to give us a sense of who the characters are and how they interact in their environments. At 11 large pages of four-row panels, the story has breathing room to explore its subjects as needed. Reading these two stories, I thought of Will Eisner’s contemporary Spirit pieces where he told an ironic short story in seven smaller pages, with his star doing a walk-on in the last few panels. Stories like Eisner’s “Ten Minutes”, “The First Man” and “The Barber” were aiming for what these two Biro-Crandall pieces achieve. These Tops entries lack Eisner’s melodrama. They take pains to downplay their events; this gives the reader authorship in deciding how dreadful, suspenseful or upsetting the stories are. Comics wouldn’t capture this sophistication again until the 1980s, when independent creators again explored this territory.

Among other standouts in this collection is a story written by Dick Briefer, one of the most idiosyncratic comics creators of its alleged golden age. Best-known for his inspired comic book version of “Frankenstein”, the cartoonist had a way with words evident in his droll dialogue and captions. This appears to be the only story he wrote for another artist.

“Our Explosive Children”, illustrated by George Tuska, is an intelligent account of an over-indulged, well-to-do young man whose arrogance and recklessness causes turmoil, death and unmarried pregnancy. Tuska’s caricatural, rounded cartooning was seldom as sober. Its calm helps leaven the melodrama of Briefer’s story. Briefer’s approach is more sensational than Biro’s, but no less invested in his characters and their relationship. The open-ended story, which asks of its readers “what are we going to do about it?” is another high spot in the book.

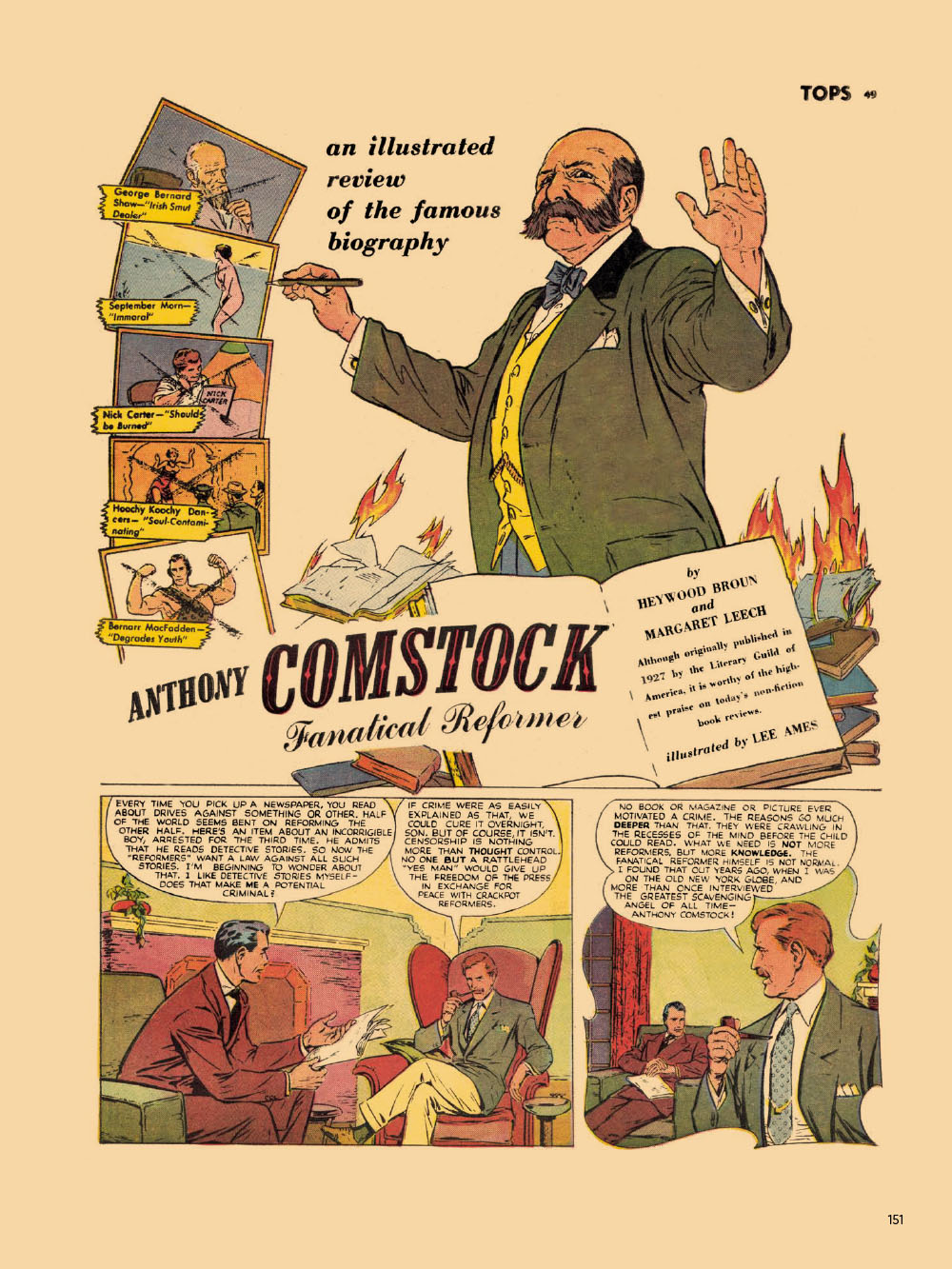

Biographical studies of Broadway legend Billy Rose and self-appointed reformer Anthony Comstock, based on prose biographies, show a lively approach to telling real-life stories in comics form. These are a far cry from the stifling scenarios of True Comics, the bland but successful title published from 1941 to 1950 by Parents’ Magazine Press.

With elegant artwork by Fred Kida, “Summer Waitress” is a solid romance story that explores a theme of classism. Kida's expressive, restrained drawings are impressive, and in concert with a well-told genre story by Virginia Hubbell (adapting Chuck Benedict), the results are a pleasant surprise.

And then there is “How Would You Live Under a World Government?” Illustrated by Bob Lubbers, it’s a fascinating piece of lefty propaganda that captures the sense post-war Americans shared that an atomic war could wipe out civilization at any time. Though hyperbolic in spots, the story is a riveting document of the tense mindset as the second World War segued into the Cold War.

There’s something of interest in every story in Tops; its prose pieces, usually the Achilles heel of the comic book, are solid. They include a minor but compelling short story by Dashiell Hammett, “The Joke on Eloise Morey”.

Designed by Keeli McCarthy, Tops is an elegant package—attractive and sensitive to its contents. This is a forgotten chapter in the abortive development of the comic book and its creators’ ambitions remain admirable. It enlightened me with its history and impressed me with its content, and that’s all I can ask of an archival volume.