For most of his life, Yoshiharu Tsuge objected to having his work translated, because there was so much Japan-specific cultural context it would be misinterpreted anywhere else. Now in his eighties, he’s relaxed his position, and in addition to The Man Without Talent, a 7-volume collection of his work will begin being published by Drawn And Quarterly this year. Still, presumably anything I write about him will miss at least some of the point. Translator Ryan Holmberg provides an introductory essay containing a good deal of useful information, but even without it, the power of The Man Without Talent is easily understood. Holmberg situates the book as fitting into a popular trend in Japanese literature called the I-novel, which are semi-autobiographical works written by men about being a loser and their problems with women and drinking. These exist in the U.S. as well and their appeal is readily graspable. Despite Tsuge’s reputation of making comics as art, and his stand-in Sukezo Sukegawa lamenting that art does not sell, The Man Without Talent ended up being a hit in Japan as the country experienced an economic downturn in the early nineties. An American audience, subject to an economy hollowed out by a recession and the rise of the gig economy, will find much to relate to here.

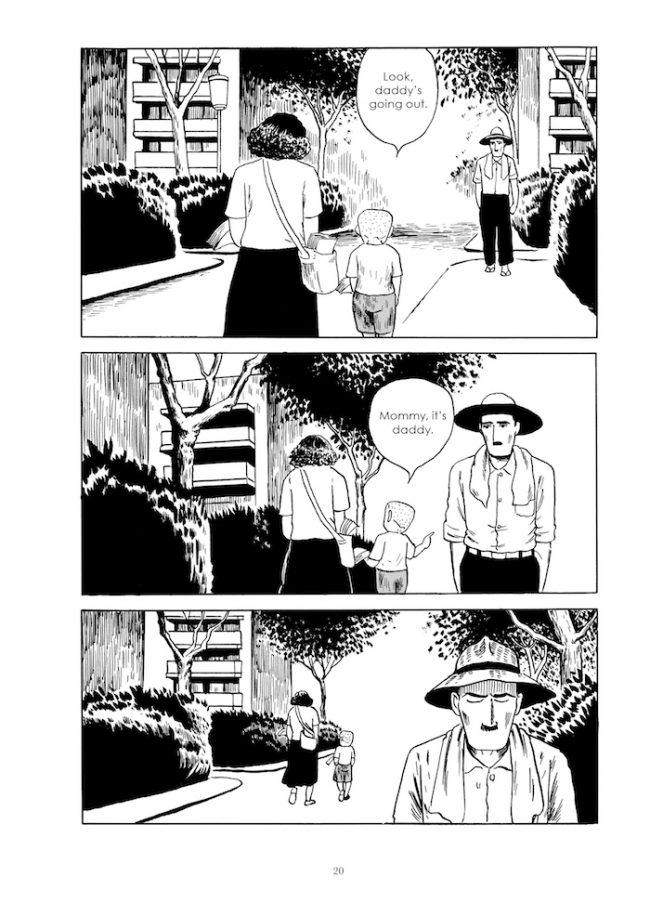

There is so much autobiographical material about being a loser in English already, in prose and comics both, that it is probably more important to explain what distinguishes Tsuge’s artistry that make it resonate on a deeper level than simply being relatable, and marks The Man Without Talent as the work of someone incredibly talented. This book came towards the end of a career, which included a stint working as an assistant to Shigeru Mizuki, whose work is well-represented in English translation. Mizuki would be best known for his cute one-eyed Kitaro character, who confronted monsters of yokai folklore among detailed depictions of rural environments. In The Man Without Talent, the backgrounds remain drawn with a high level of detail, even as the protagonist is not cute at all, and actually fairly repulsive. Tsuge’s skill at drawing backgrounds allows the pages to be attractive and easily moved through despite Sukezo’s omnipresence. His is a truly pitiable character design, one of the least attractive I can remember, with a dumb mustache and chicken legs. On the cover he’s drooling, as his pot belly falls out from under his shirt. His wife cannot look at him, seemingly. For the first half of the book, her face is either turned away from the viewer or covered by her hands.

Tsuge was also decades deep into his own body of work, which began with telling stories that were surrealist and dreamlike. I’m familiar with one of these, which was published in the U.S. under the name “Screw-Style” in an issue of The Comics Journal. There’s a sense in that story, based on a dream, that the landscape the characters navigate is symbolic and befuddling, that persists here as well, even in a naturalistic, quasi-autobiographical context. Sukezo Sukegawa is a hapless man, hoping to navigate the landscape and find something of value, so that he can make a living and stop hating himself. By rendering the outside world in such textured shadowy detail, Tsuge is able to capture the overwhelming quality of reality that is such a crucial aspect of the helpless loser experience.

Sukezo sells stones, gathered from a river. This might seem like a cultural thing without parallel in the West, but for the fact that the stones don’t actually sell and it’s a completely unsuccessful business. It’s an attempt to make the surrounding world work for him, to manipulate the objects around him become invested with value he can capitalize on, but it fails because he lives nowhere near the rivers and waterfalls where valuable stones are found, and any trend where stones were perceived as beautiful enough to buy is so far in the past no one can remember when it was. Books about valuable stones are provided to him by a bookseller, whose own business is failing, and who lays on the shop’s floor. Sukezo exists in a world where no one has money or prospects, where everyone is trying to save money by not buying anything, and while there are ideas for services that could be provided to the poor, there are not the resources to invest in realizing them. Sukezo was once a cartoonist, but no one’s getting in touch with him now, and if he contacts an editor, he will be perceived as desperate in a way that would sabotage his already-collapsed career. A talent that is not monetizable might as well not exist, and the whims of the market are fickle. In a flashback, we see how a brief stint selling repaired cameras was able to begin being successful, before the market changed and ruined him again.

The book ends up being about how the need to have money under capitalism manufactures self-loathing that leads to an even greater inability to act. An essay might be able to articulately describe how such forces control our lives, but none are going to be able to capture the experience of feeling like an idiot whose family hates hims as effectively as Tsuge does. With Sukezo’s mustache covering his mouth, he’s rendered with the appearance of voicelessness even as he speaks. His emotional responses are communicated effectively by big drops of sweat flying off his face, in constant shame.

An understandable desire to disappear seems to connect Sukezo’s predicament to his author’s desire for his work to not be published internationally. The book’s concluding chapter places Sukezo’s feelings in the context of Japanese history and cultural character, telling the story of a wandering poet. This ending doesn’t transform the book, but it does perhaps provide some context to understand its accomplishment. While modernity in America has its discontents, what enters into the book at the end is the idea of a haiku’s focus on the passage of time, and perhaps it is coming from a culture of Buddhism that enables the book to so skillfully meditate on the basic impossibility of simply existing.