Consider garage rock, the popular music genre that proliferated throughout the United States in the mid-to-late 1960s and still thrives today, its rigid parameters forswearing innovation. Blues-based, distorted, and structurally basic, garage rock by definition offers little variety. Compare something like The Sonics' 1964 single “The Witch” with the latest SoundCloud release of any Burger Records darling, and you’ll get an idea of how sonically timeless—and stylistically limited—the genre is. Given the narrow pool of precedents to draw from, contemporary garage rock songs are all, to a degree, about the idea of garage rock. The savvy garage rock band relies on a novel point of view and the unexpected juxtaposition of familiar tropes (e.g. attach a Byrds verse to a Stone chorus and you got something cookin’) to supersede stagnation.

Written by Keenan Marshall Keller and drawn by Tom Neely, The Humans is the comics equivalent of garage rock, an impeccably curated collection of stock characters, familiar scenarios, and unconcealed references to its pop cultural antecedents. And like the best garage bands it makes the most of a thin conceit. That conceit revolves around the travails of the titular biker gang, a Bakersfield-headquartered group of simian roughnecks, in an alternate Planet of the Apes-esque 1970s America in which apes have supplanted humans as the dominant species. But more than that it’s a comic about the idea of itself, a pretend artifact of '70s underground pulp that could never have really existed in the '70s.

Even given Image Comics’ increasingly catholic tastes, The Humans is a bold project for the publisher. The book wouldn’t be out of place on the roster of a boutique publisher like Koyama, but I wonder if that audience is even aware of The Humans. Image is no longer the house that variant Spawn covers built but neither is it the most logical venue for The Humans’ brand of wacky, self-referential comix-with-an-x pastiche. Most early reviews focused on the Russ Meyers school of '70s exploitation cinema as a reference point, but this volume, which collects the ongoing series’ first five installments, is more intertextually complex than that.

The Humans’ watering hole of choice is Kirby’s Saloon, a tip of the hat to the creator of Kamandi, arguably Jack Kirby’s best '70s-era work, about anthropomorphized animal clans in a desolate post-apocalyptic earth where most humans are kept as pets or used for labor, an idea The Humans borrows wholesale. Backgrounds are littered with mute, shackled humans, and one standout sequence depicts a pair of capital-H Humans pitting their human slaves against one another in a cockfighting-style competition.

Neely’s touch is lighter than Kirby’s. He lacks the King’s confident, bold strokes, but his thinner lines are well suited to the fluid gestures of a biker brawl or a motorcycle race. His character designs are varied and distinct, no mean feat for a book with a limited number of subspecies to work with, yet consistent in their bell-bottomed, spindly-legged Hanna Barbera-ness. Nonetheless, he shares Kirby’s predilection for densely populated double-paged splashes.

All of which speaks, in the best way, to Neely’s artistic indulgence. In particular in his layouts, Neely brings an eagerness to experiment (and to show off) that is commendable if not always successful. This psychedelic freak-out, for instance, would have made for a great cover but in the context of the book leads to some wonky pacing; what’s meant to convey an endless night of partying scans with a brevity that belies the bacchanalian extravagance depicted. Ostentation for ostentation’s sake, it’s less of a montage and more of a blacklight poster.

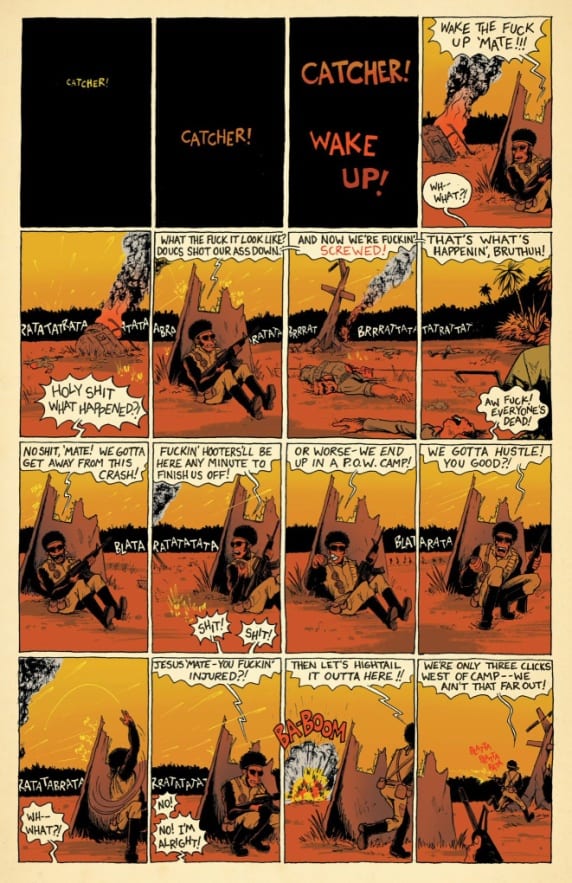

A much defter manipulation of narrative time is on display in lead character Johnny’s Vietnam flashback. This cramped 16-panel grid, drawn from Johnny’s first-person point of view, follows Johnny’s woozy line-of-sight as he gradually takes in the wreckage of his crashed helicopter, tracking his comrade-in-arms’ precise movements as his narrow consciousness struggles to comprehend the carnage that surrounds him. The next page broadens the scope to cinematic widescreen so as to lend a palatable distance to one of The Humans’ many scenes of gratuitous B-movie bloodshed.

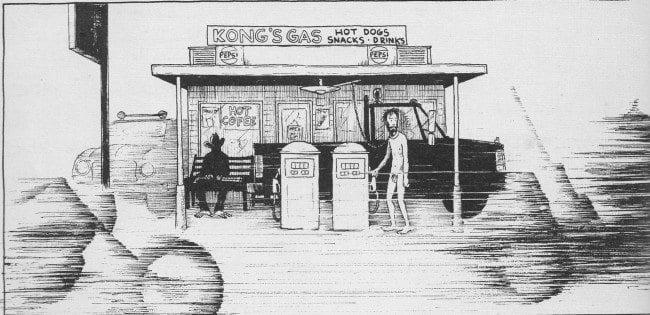

Kristina Collantes’ coloring is expressive and, for a book with such psychedelic underpinnings, impressively restrained. She tends to alternate between pages and panels with a preponderance of either warm tones or cool tones, striking a pleasantly uneasy balance between vibrancy and garishness. Quieter, dialogue-heavy scenes typically have the colder, subdued look of '70s film stock. And of course, when the page warrants a cornucopia of acid-flashback neons, Collantes knows when to go for broke. The book’s first twenty or so pages, previously self-published as The Humans #0, are black-and-white. This starker art accentuates Neely’s nicely kinetic sense of motion, a quality which the color art neuters somewhat. Still, the color art is superior for the balance Collantes adds to Neely’s occasionally busy pages.

If I’ve said little about the storyline, it’s because Keller mines a similar pop cultural detritus as contemporaries like Ben Marra and Johnny Ryan, whose comics revel in seemingly dumb, confrontationally unironic set pieces of hyper-violence and vulgarity. (One member of The Humans is even named after Marra, and both Marra and Ryan provide pinups in the book’s supplementary pages.) However, this is not to undermine Keller’s craft. His approach to this milieu is tonally intricate. Narratively Johnny’s post-war trauma is played with a straight face, the depiction of Vietnam-era societal turbulence as harrowing as the kind of thing you’d find in an old issue of Inner City Romance, but it’s all painted with the same gleeful, candy-colored exhibitionism the book applies to biker movies clichés. Sure, the Viet Cong are portrayed as snub-nosed monkeys and the American troops as chimps, but a spiritual successor to Maus this is not. Disillusion and rage belong solely to the characters, not the creators, and The Humans eschews the implied satirical bite characteristic of a Marra book. Even still, that tension between serious subject matter and goofy presentation makes for a book that (mostly) transcends immature provocation. If Ryan’s Prison Pit is for the inner ten-year-old, The Humans is for the inner stoned teenager—appropriately enough, the ideal consumer of garage rock.

And it’s worth noting that each issue of The Humans comes with its own two-song soundtrack, available at the series’ official website. All the songs, with “Nife Fite” and “Ride to Die” being representative titles, are revved up, distorted, messy, and totally lacking in subtlety, the perfect audio accompaniment for this loud and surprisingly ambitious series.