Raina Telgemeier is the patron saint for young cartoonists toiling in art school, hoping for a big break and a publishing contract. After graduating from the School of Visual Arts in New York, her publishing history consisted of a handful of short minicomics, an appearance in a Meathaus-related collection, and appearances in a few other anthologies, including one called Broad Appeal published by the Friends of Lulu. Her story in that book gained the notice of an editor at Scholastic, who let Telgemeier pitch her an idea. While she had already begun serializing her career-changing book Smile online, she pitched doing adaptations of Ann M. Martin's Baby-Sitters Club books. She adapted four of them, with modest success, before Scholastic opted to publish Smile.

That book, an autobiographical account of Telgemeier's painful and complicated history of dental problems along with other personal anecdotes, touched a nerve with a number of younger readers, and especially girls. Telgemeier's understanding that the more specific one gets in telling one's story, the more relatable it becomes gave the work an authenticity that struck a chord. When one throws in a smooth, pleasant drawing style that's equal parts Bill Watterson, Keiji Nakazawa, Bill Amend, and Lynn Johnston, you've got an artist who knows how to appeal to a wide audience without specifically adhering to a particular visual aesthetic. That said, if this was another era, Telgemeier would have no doubt been a successful syndicated cartoonist.

Instead, in this era, she merely has six of the top ten books on the New York Times' Paperback Graphic Books list. 2010's Smile is #3 and has been on the list for 181 weeks. 2012's Drama is #2 and has been on for 122 weeks. Telgemeier has been such a phenomenon, aided in part by her personable presence on her frequent nationwide tours, that Scholastic has gone back and reprinted her Baby-Sitters Club adaptations, this time (wisely) in color. Those books sit at #7, #8, and #10, and I imagine the fourth and final volume will crash the list when it's released next year. Her current book, and the subject of this review, Sisters, is #5 on the list and it's been there for 65 weeks. In essence, her readers pick up one pick and immediately want everything she's written, which makes sense because when they do read, children tend to be obsessive and voracious readers. Throw in Eisner Awards for both Smile and Sisters and plaudits from assorted libraries and kid-lit lists, and it's obvious that Telgemeier has carved out a career path that's come at the right place and the right time.

Instead, in this era, she merely has six of the top ten books on the New York Times' Paperback Graphic Books list. 2010's Smile is #3 and has been on the list for 181 weeks. 2012's Drama is #2 and has been on for 122 weeks. Telgemeier has been such a phenomenon, aided in part by her personable presence on her frequent nationwide tours, that Scholastic has gone back and reprinted her Baby-Sitters Club adaptations, this time (wisely) in color. Those books sit at #7, #8, and #10, and I imagine the fourth and final volume will crash the list when it's released next year. Her current book, and the subject of this review, Sisters, is #5 on the list and it's been there for 65 weeks. In essence, her readers pick up one pick and immediately want everything she's written, which makes sense because when they do read, children tend to be obsessive and voracious readers. Throw in Eisner Awards for both Smile and Sisters and plaudits from assorted libraries and kid-lit lists, and it's obvious that Telgemeier has carved out a career path that's come at the right place and the right time.

What's interesting to me as a critic is that Telgemeier is talented enough and her appeal strong enough that she was able to get better in public on a stage with much more at stake and with a far greater audience than most young cartoonists. The Baby-Sitters Club books wound up being her comics PhD, as she was able to learn about how to pace and structure a long plot and hit specific thematic points working with vividly realized characters. Those characters tended to be somewhat rigidly defined (this one's the jock! this one's the fashionista!), but it was no doubt valuable training ground--especially since the original versions of the books struck such a chord with Telegemeier as a teen. As an artist, however, the original books simply beg for color, because Telgemeier's spare line leaves huge gaps on each page that draw the eye away from the line.

One can see some of the lessons she learned from the BSC assignment in Smile. However, Telgemeier struggled to mesh three separate elements of memoir with her interest in providing thematic structure, and as such, the book is all over the place. It's to her credit that the themes she taps into--hanging onto friends who aren't really very nice to you, dealing with pain and humiliation--are so vivid and underserved in a graphic format that it didn't seem to matter much to her readers. That said, Telegemeier took a major leap forward with Drama, a work of fiction that was nonetheless based on her experience as a drama department "techie" in high school. Here, the structure of the plot and characterization is smoother and also more sophisticated, as she matter-of-factly introduces queer characters into the mix.

If those books vaulted her into success, Sisters helped cement that status. It's easily her best book to date, and the autobiographical structure of the book complements Smile as it acts as a sort of sequel. It's a story about the tumultuous relationship between Telgemeier and her younger sister, Amara, and it contains a lot of hard truths about the ways in which families develop and fall apart. One of the reasons why the book is so effective is that the actual story takes place in a two-week timespan during a somewhat arduous car trip with Raina, Amara, their mother, and younger brother Will. Throughout the book, Telgemeier employs flashbacks to emphasize key elements in her relationship with her sister as well as the family itself.

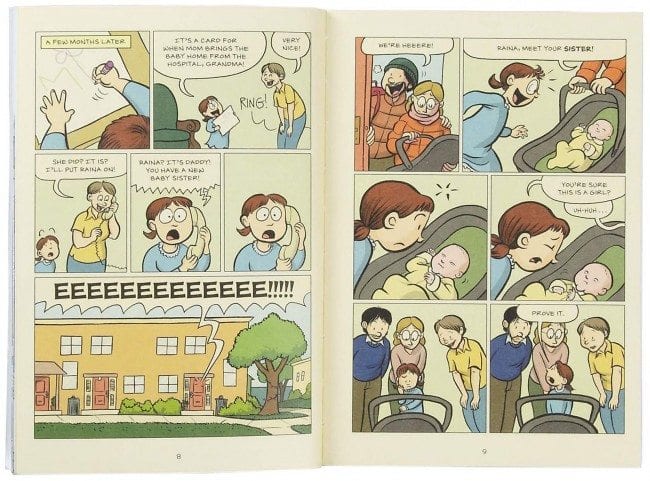

Living in San Francisco, the family gets increasingly cramped in their small apartment as more kids are born. Young Raina desperately wanted a sister, but finds that the one she gets is irascible and prefers being left alone. Amara's a self-styled outsider who doesn't fit in and doesn't care to. That's in contrast to people-pleaser Raina, and while the narrative is presented from Telgemeier's point of view and our initial inclination is to feel sorry for Raina and wonder what Amara's problem is, Telgemeier the artist slowly and subtly alters that impression as the book proceeds.

Indeed, as Telgemeier depicts the family's apartment as becoming increasingly cramped and noisy, she depicts herself as finding ways to escape--usually with her Walkman drowning out the din. Depicting the book from her point of view, we can understand why Raina wants to escape: grouchy and obsessive sister, loud and silly brother. However, in a surprisingly harrowing scene where she and her sister are left in the broken-down van in the middle of nowhere as her mother leaves them to try to find a ride, things get desperate and real between the two of them. Raina has suddenly noticed that things between her mom and dad aren't rosy at the moment--a revelation that had not escaped her sister. Raina learns that Amara resents her for tuning her and everyone else out with her Walkman, for only being nice to her when the cousins they were visiting weren't giving her the time of day, and essentially being far more observant than Raina gave her credit for. The end of the book doesn't wrap up every problem and bring it to a neat end, but it does begin the possibility of dialogue and finding a way to get along.

What makes the book work is that Telgemeier piles on humorous anecdote after humorous anecdote, effectively masking the book's overall themes in service of making it funny. It's still not hard to find the through-lines that reflect the themes, but there's far more restraint here than in Smile, which is at times thuddingly obvious. In service of those gags, Telgemeier's line became much more rubbery and even explosive, resembling Peter Bagge's work in The Bradleys more than Johnston's more gentle family saga. Eyeballs pop, young Raina demands that her parents prove that her new baby sister is actually a girl, pets die in increasingly ludicrous ways (the chameleon being eating by the crickets it was supposed to eat was especially funny and awful), the menace of a lost pet snake is a recurring gag and mouths are agape in screams. If Smile had a touch of a slightly melodramatic after-school special, then Sisters is far more raw and real. The loose plot that nonetheless has a built-in storytelling structure (the road trip) is the perfect template for exploring the ways in which families fight and ultimately either find a way to work together or else fragment.

Just as Smile appealed to teens struggling with getting braces and the unforgiving social order of school, so will Sisters appeal to those struggling with their own sibling and parental relationships. The specifics will differ, but Telgemeier's facility in depicting real emotions rather than melodramatic projections of same gives the book a sense of authenticity that is immediately recognizable.