This collection was surprisingly difficult to write a review for. I liked very little of it, on either a personal or artistic level, yet couldn’t get away from the feeling that that reaction had to be unfair. After all, Bill Kartalopoulos (series editor for The Best American Comics) seems to have practically anticipated it. He introduces the book by thoughtfully acknowledging that it is, inevitably, a work of criticism, and emphasizes that good criticism depends on humility:

Like anyone else, I have opinions: I have tastes, I have preferences, I have aesthetic biases. Like any critic, I believe that my opinions are informed: I believe that even my reflexive opinions—my gut reactions—are informed by a valid point of view based on years of engagement with comics…But engaging work critically requires one to be aware of one’s predispositions, and, crucially, to be willing to put them aside, to question them, and to revise them. A critic needs to be humble enough to acknowledge that they may not have totally understood a work the first time.

But how to humbly express your suspicion that something wasn’t very good? I read The Best American Comics 2018 hyper-aware that my own gut reactions were not informed by the years of comic-reading and making that Kartalopoulos and editor Phoebe Gloeckner have. Nor have I read any comics published between September 1, 2016 and August 31 2017, other than the ones in this book. In other words, I have no honest way to judge, based on either the editors’ criteria or my own, whether these selections really are the best that American comics had to offer last year. It would be disingenuous to try. I can only grope at the bit of elephant in front of me, and think about what it means that someone might call it “best.”

There are two obvious bents in The Best American Comics 2018. First, towards the auto and semi-autobiographical (nearly half of the 33 comics fall into this category). Second, towards the non-narrative, or otherwise “art”-y and experimental. Those are perfectly fine genres, and there’s no reason that they couldn’t happen to comprise the plurality of the year’s best comics, but the fact that their exemplars were simultaneously overrepresented and underwhelming left me with the distinct feeling of bias.

It’s the only way that I can explain the inclusion of five different comics about an author’s art education or early comic-making years, none of which give the reader a compelling reason to care about those stories. (Even one of the strongest ones, Playground of My Mind, Julia Jacquette’s “graphic reminiscence” of New York City’s modernist playgrounds, left me confused as to why I should be interested in how the playgrounds affected Julia Jacquette in particular. She makes an effort to make the playgrounds seem interesting, but doesn’t similarly justify herself.) In fact, because the collection contains so many of these comics-about-making-comics, the impact of each one, the sense that it is a uniquely important idea, becomes progressively diluted.

The thing about bias, and the reason critics mention it, is that it means an artist has to work less hard to create effects in its audience. They don’t have to refine quite so much. They don’t have to seduce. They don’t, in other words, have to do quite so much art.

Here’s a good place to compare. Take the three different comics in this collection that deal, broadly, with the feminine grotesque (ie, general coping with being embodied, from a female perspective), and their three different tacks. How To Be Alive (Tara Booth) is a series of wry, visual caricatures of the author’s more undignified moments. Angloid, Part 2 (Alex Graham) sticks to narrative, relating mildly surreal interludes in the life of the artist, in that way I associate with TV shows like Girls. UGLY (Chloë Perkis), on the other other hand, goes entirely figurative. And of the three, I found it was the one I respected most. While the other two linger on the sort of self-deprecation that mostly ends up coming off as self-absorbed, UGLY barrels past it to look at self-hatred for the cartoonish thing it is. It doesn’t bother to be cute. It’s simply absurd, and, well--ugly. The comic is entirely about the author’s feelings, but crucially, it digests them for the reader. It doesn’t merely represent. It plays. It contextualizes. It pushes. And I appreciate that.

[compare: three approaches to menstruation]

Or compare that expressiveness to Things More Likely to Kill You Than… (Laura Pallmall) a piece of political pamphleteering about as ideological as Socialist Realism. The comic is a series of images of red-culture Americana, each of which is, unsurprisingly, more likely to kill the average American than ISIS. Whether or not I agree with the politics behind it doesn’t even matter. As art it is insultingly literal. At least Banksy makes you make pleasant mental leaps. Hell, even someone as kitsch as Pawel Kuczynski has a grasp of imagery and figuration.

Or take “Sam’s Story,” an excerpt from Rolling Blackouts, Sarah Glidden’s journalistic account of media interactions with locals in Syria and Iraq. It’s a fascinating project, and easy to respect the effort behind it, but the execution is so wordy, and so visually flat that it practically dares you to pay attention to it. It looks like a court illustration, or a wikihow article. (Which okay, could be cool, in theory). Is this simply the artist’s style? Were they afraid that any hint of entertainment would profane the gravity of its subject matter? Would distract?

It’s not that I wish “Sam’s Story” had been entertaining in some lurid, adolescent way. But if we’re talking bias, my bias is to think it’s an artist’s responsibility to interest its audience, to make it notice what they want it to notice, and feel what they want it to feel. And somehow I don’t think that Glidden wants the audience to feel nothing.

Hostage (Guy Delisle) has a similar problem, though I wouldn’t call it flat. Visually, it’s more like Hostage is...chaste. Nearly cute. A peculiar choice for a true war hostage story, and one that doesn’t seem entirely purposeful (what it does seem to be going for is a sort of Trümmerliteratur brutalism). With both of these works, I left confused as to why the story had been rendered into a comics format in the first place. If an author isn’t interested in making the most of what visual art can add to a narrative, why bother with it?

[pictured: faces and squares]

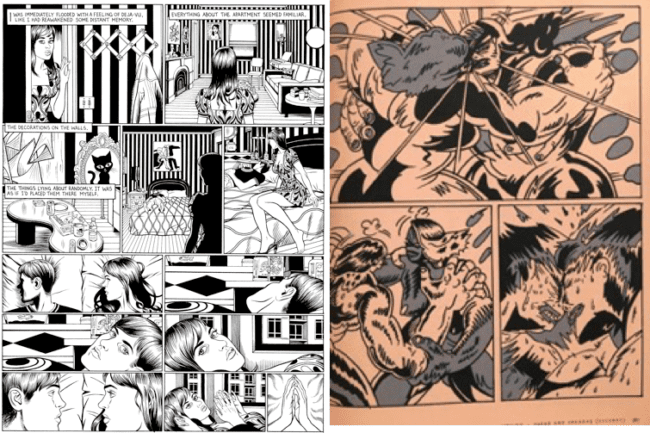

The works that made the biggest impression were the ones that made full use of the medium. Works like The Shaolin Cowboy: Who’ll Stop The Reign (Geoff Darrow), a comic-booky yarn about a pig on a mission of vengeance, with a visual style reminiscent of early Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. The Shaolin Cowboy is strong not because it looks “professional” or “mainstream,” or even because it tells a story. It’s strong because it feels complete. I could react to it as a “done” artistic entity. There is a security in that, in knowing that the artist is in control of what they’re doing. Whether or not the reader likes the work, they at least come away with some clarity about what they’ve experienced. Echoes Into Eternity (D. J. Bryant) felt similarly in control of its gender-bending, Cortázar-ish story. It’s a bit simplistic, idea-wise, but it takes those ideas to completion, building up a rich, geometric visual language where curves and angles subtly switch places as the story progresses. Yazar and Arkadas (Lale Westvind), just has a refreshingly strong sense of visual storytelling, managing to be clean and dynamic, while still maintaining an individual, original style.

[pictured: geometric motifs in Echoes Into Eternity, vivid action in Yazar and Arkadas]

The real problem with The Best American Comics 2018 is not actually the comics themselves, I’ve realized. The collection does, at the end of the day, contain a respectable variety of comics, most of which I can tilt my head and understand the merit of. The problem is the lack of editorializing. Truly, I wanted to read it in the spirit of Kartalopoulos’s introduction. I wanted to set aside my biases. I wanted to be wrong. Mostly, I wanted to know why I was reading these comics and not others. I wanted to be convinced. But no one was doing any convincing. If this were any other comic-reading experience, that decision would make sense. Certainly if one picks up a graphic novel, one doesn’t expect it to include authorial asides telling the reader what to think of it. But this is not a graphic novel. The editors acknowledge that it’s a critical enterprise, albeit one influenced by personal taste. It definitely doesn’t feel like a coherent reading experience, given that the comics are organized alphabetically--rather than in some more directed manner--and are often decontextualized excerpts*. Not to mention the unadorned list of also-rans in the back. How does one read that?

*(Take, for example, the excerpt chosen from Sunburning, in which author Keiler Roberts documents her daily family life. Sunburning is introduced merely as an autobiographical comic, and the section included gives the impression that it’s about as substantial as a long-winded Family Circus. I had no idea that the comic was actually about Roberts’ diagnosis of MS, which, while that doesn’t necessarily make the depiction of domestic life more interesting, it at least gives it some purpose.)

Perhaps it’s silly to take issue with the format of a long-running series, and perhaps I wouldn’t care if I liked more of the comics myself, but without editorial guidance, what makes this book more than an expensive listicle? It feels like a bait and switch, to pick up an evaluation that then fails to evaluate. If anything, fittingly, the book as a whole reminded me of the comics themselves. A bizarre combination of being opinionated, and being averse to one of the most fundamental aspects of artfulness: persuasion.