“My blood tastes like metal!”

“Even at the top, there’s always someone better.”

“Why continue if you can’t take it?”

“We’re all just killing time until we die.”

“What’s the point of all of this?” “To get stronger.”

“How can you hope to cross an ocean on such scrawny wings?”

“He wasn’t just good, y’know. He was beautiful…unbelievably beautiful.”

“It’s hard to recover from public humiliation like this.”

“Then is it simply that you have strength to spare?”

“I used to believe…in a righteous hero who couldn’t lose, more or less.”

“It’s envy, yes, but I’m also in awe of him.”

“Your talent will just rust away! Like a bicycle left out in the rain.”

For its deserved reputation in Taiyo Matsumoto’s oeuvre, it would be easy to forget that Ping Pong began as the work of a humbled artist in the wake of an ambitious commercial failure. In Matsumoto’s own recollections from his 2013 TCAF appearance, the increasingly personal turn of his series Number Five did not translate into sales, and his publisher sought from his next work something a bit more conventionally marketable, a sports manga. Working quickly, Matsumoto abandoned the scope of his prior world-creating epic and went small, operating at a mundane scale in a return to the genre where he began.[1] However, it is clear from page one that Ping Pong is not to be Matsumoto’s surrender whatsoever, but a progression of his expressionistic and empathetic artistic sensibility. Ping Pong takes the commercially viable generic patter of the sports manga as the groundwork for quiet, personal digressions that are tender and beautiful.

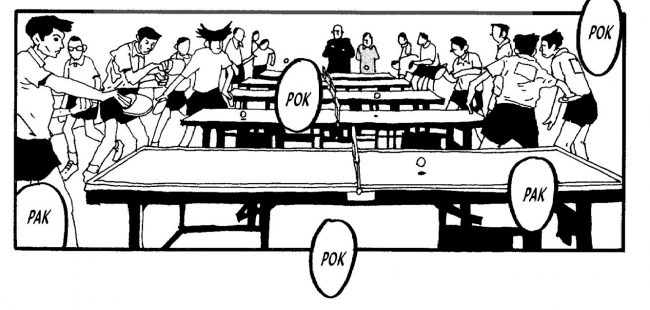

As the Shonen Jump mantra famously culled from a reader survey goes, Ping Pong is about friendship, rivalry and ambition. But in the same breath, the series is about exhaustion and regret, repression, and the reaching of personal limits. Ping Pong is about the friendship of two boys raised in the same foster home, Makoto Tsukimoto and Yutaka Hoshino, known to their friends and to each other as Smile and Peco (the Japanese onomatopoeia for a grin) respectively. Both have been playing ping pong from a young age and both are now practicing in a high school program to compete on a national level. Smile, as Peco often remarks, never smiles, his expressions hidden behind his glasses. He rarely speaks but often hums to himself, fidgeting with a Rubiks Cube pensively and practicing methodically, socially detached apart from Peco, a little bit on the spectrum. In contrast, Peco is a ball of hyperactive, unfocused energy, unable to keep quiet, sit still, hold back his titular grin at any time, often rattling off facts about different brands of candy or chewing gum. Without the sport these boys would likely be completely isolated by these sorts of behavior, especially in groups of schoolchildren raised to police norms. Yet the sport itself is a hotbed of societal pressures and demands to succeed, and although accepted for their abilities Smile and Peco remain in a world apart from others.

The manga unfolds as a series of matches gradually introducing an ensemble of participants in the sport all struggling with some form of conflict between love of the game and the draining emotional and physical pressures to remain at the peak of abilities and succeed within the crushing, relentless demands of competition. There’s Wang, called “China” by fascinated Japanese boys, a former top player who hopes to overcome his defeat in his home country by way of victory in Japan’s smaller competitive circuit. There’s Koizumi, the boys’ coach, in his youth a legendary player nicknamed “Joe Butterfly,” pursuing Tsukimoto’s potential relentlessly in hopes of recapturing his glory days and amending the decision that cost him his career. There’s Dragon and Demon, two talented players from a rival school, Dragon being calmly in love with the sport and self-assured of his abilities and Demon full of bluster hiding deep insecurities and fear of failure. In each, a psychology of conflict emerges around their involvement in (and detachment from) the game, the love of playing ping pong and the cost of taking it further. Smile stands poised to rise greatly in the sport, having in him a clear and intense natural talent, his competence and potential becoming a fact that every character must privately reckon with – Smile included.

Tsukimoto’s cold exterior is unraveled not by any moment of drama, some unveiling of Naruto tears or any sort of declaration of something, but in his technique, his game. He plays a carefully calculated match, matches where he is stronger, matches where he is weaker, but the expert observers of the sport notice immediately that what he calculates so efficiently as plays is not how he might win but a compassionate reflection of his opponent’s emotional inner world. To put it simply, win or lose he can’t bear to hurt them. It’s a heartfelt, admirable desire but one that renders his emotional disconnect all the more painfully vivid. He cannot see the competition as a social sphere that operates differently from the mundane world, he fears personally hurting people he cannot express his affection for in words and articulates this in a structured competition where all participants expect and understand that there will be dominance and failure by design, even though of course it does hurt for real. Tsukimoto can’t connect to people comfortably outside of competitive ping pong’s paradigm, and within it he is paralyzed with fear and self-abjection, struggling with the suggesting to slough off his only accessible means of showing kindness and imagining himself a killer robot, with blood like iron. I hesitate to write these words as any comparison to a diagnostic label can harm and reduce as much as help and elevate, but Tsukimoto is a brilliant portrayal of the internal conflicts to level with conventional social expectations that many autistic people know all too well.

Sports and shonen action manga are psychodramas. Even with the most decompressed, kinetic action (and perhaps, indeed, especially with this), tension and excitement is racked up in the genre by spending time inside the heads of combatants and spectators alike. In a generic battle manga, every turn and action is joined to hero, ally, antagonist individually looking on, mouth agape, thinking to themselves “He is good! Who is he? Who am I? How do I respond to this?” It is an approach to pacing that often generates absurdity and tedium (Dragon Ball Z, especially in anime form), but in Matsumoto’s hands the formula is exploited for explosively nonlinear meditations, the strike of the paddle setting off flurries of memories, symbols, anxieties, dreams and mantras, flickering before the players’ eyes as they draw in breath. Questions after matches – “Why did you let him win?” “How will I become strong now?” “What happens next, now that this is over?” – take on an existential, deeply personal flavor, which is of course the very draw of sports manga and shonen.

Where the work becomes unique is in its fixation on loss and limitation. Climaxes in competition manga often involve the hero conceding victory in a manner that reveals his moral excellence or a hidden ability such as extraordinary self-control or an untapped superpowerful technique – in other words, the defeats are in fact real victories. In Ping Pong, this fantasy of a winning loss is flatly crushed. If a game is lost in this competitive sport, your career in its niche confines is over, totally, a harsh truth we return to again and again. The winners must reckon with the level of ability and precision they must maintain to (perhaps) remain in the position they’ve reached and whether it is worth the pressure, the exhaustion, the opposition of the self to others. The losers have to reckon with what comes next, a life after the sport, wondering where they went wrong, wondering where now they should go. These matches are suffused with exhaustion and desperation and culminate in lingering existential crises. Matsumoto refuses to lend competitive sport itself the humanity and optimism the genre so often imbues the paradigm with, saving that empathetic loving gaze for his characters, their quiet, internal struggles, and indeed the sport of ping pong itself, the movements of its most engaged players.

In Ping Pong, the kinetic imagination of Matsumoto’s stark pre-watercolor style is redirected from the awesome vistas of Tekkonkinkreet and Number Five entirely onto the human body, the high-contrast tension of limbs attuned to sport. Games do not end in victory but in exhaustion, the striking of limits. I wouldn’t always call Matsumoto’s work homoerotic, but I can’t think of many comics that capture the potentials of men to be incredibly beautiful so distinctively as Ping Pong. This wonderful sense of physicality extends to the comics quiet moments as well, the boys moseying around in empty gymnasiums, animated by conversation. There’s a definition to their relationships in how they move and speak around each other and apart. Matsumoto’s grasp of body language lends his forms at once kineticism and warmth, whether in motion or in repose.

Eagle-eyed readers of this review may have figured out that the summation of Ping Pong’s original circumstances of publication I began with has strongly colored my reading of the comic. In the process of creating Ping Pong, Matsumoto was struggling with creative fatigue – like his character Wang’s exodus to Japan, Matsumoto was under pressure to succeed in an arena seemingly far less ambitious in scope yet where the slightest misstep could end his career. The anxieties to go on amid constraints – can I do this? why should I do it? have I lost it? – are overwhelmingly reflected in the text. Ironically, this work intended for greater commercial appeal sets the tenor for the loosely autobiographical mode of what was to come in much of Matsumoto’s late period with Gogo Monster (arguably his most experimental, anticommercial work) and the I-novel Sunny. If these three works form a trilogy of comics about foster children, then perhaps Ping Pong begins at the end of where most coming of age stories begin, Smile being in a sense the adolescent maturation of the quiet boy peering out behind thick-rimmed glasses amid the rigors of grade school in GoGo Monster and who enters the foster care system at the beginning of Sunny. At the same TCAF event mentioned at the beginning of this article Matsumoto identified the quiet boy in Sunny as himself, and the biographical thread becomes stronger with the awareness that Matsumoto began his career as a manga artist after abandoning ambitions to make it as a world-class soccer player. Ping Pong’s aimless teens at times also seem to echo the melancholic fascination with delinquents explored in Blue Spring, which in that book’s afterward Matsumoto describes as a preoccupation of his quiet teenage years. With Ping Pong, Matsumoto’s intensely personal anxieties and desires fill in the outlines of a recognizable genre form, exploiting that form’s accessibility to draw us into what might be his most emotionally intimate work.

A person can only handle high performance so long. “There is always someone better,” as Tsukimoto’s coach Koizumi muses, but at the top of our own games we can only ever really perform a little less well than ourselves. Ping Pong is a comic about the incredible and desolate lives of the so-called high functioning, the beautiful drive, the painful isolation, the capabilities we too often fail to recognize in ourselves and the agony of finally noticing the beautiful possibilities as they seem to be slipping out of reach. Failure and longing are central, defining experiences in this comic – there is an almost liberating excitement mixed with the melancholy when characters realize they have failed to live up to the private voice in their thoughts demanding that they never give up. Matsumoto’s work has never been about self-destruction but self-acceptance, finding a home within the sadness.

[1] Matsumoto’s debut serial was a baseball manga, followed by a boxing manga. Ping Pong to a certain extent also revisits the schoolyard settings of the juvenile delinquent short stories collected in his early masterpiece Blue Spring.