Nick Moss, the central character of In, feels like a nearly pure stand-in for author Will McPhail. At least, he does if you judge strictly by the popular New Yorker cartoonist’s Instagram bio and whatever picture of him pops up first in a Google search. Nick is a freelance illustrator with an encyclopedic knowledge of fonts who aspires to become a known regular in every coffee shop within a two-mile radius. He is also scrupulously designed to reveal nothing about McPhail or his values. Nick is a perfectly empty vessel, and anyone with even a passing familiarity with straight white male autobiographical fiction will probably give a resigned sigh of recognition when Nick Moss immediately launches into a traumatic memory from his childhood.

It’s a trap. Nick’s many surface-level attributes are ultimately revealed to be coiled self-protection mechanisms as the narrative turns from celebrating to rejecting them. After establishing Nick’s bland quirks and mundane routine, McPhail sneakily backdoors a compelling story about solipsism, chit-chat, and how to navigate the vast emotional distance that you’ve spent most of your life purposefully fostering between yourself and others. Nick Moss turns out to be an inversion of the typical Journey of Self Discovery protagonist, in that he doesn’t really have a rich inner life and, even at the end of the book, doesn’t really expect others to either.

Nick’s story manages to be touching and powerful because it subverts the expectations of an autobiography. On the whole, though, In is a bit of a mess. The framing puts it at a disadvantage that McPhail never quite overcomes. Even if it eventually pays off, Nick’s socially awkward, B-grade comedic material takes up half the book. Frontloaded with blithe observational yuks, the whole tone of the book is thrown off. Then there’s some vague gesturing toward a conversation about race that never actually materializes, which gives the book an off-putting undertone. It’s as if McPhail is questioning the value of a straight white male autobiographical work in contemporary culture, but still feels compelled to write one.

McPhail also seems to have trouble translating some of his strengths as a one-panel cartoonist into a full-length graphic novel. McPhail’s work for the New Yorker has a keen irony, girded by elegant composition that drives your eye precisely where in needs to go to get the story. It’s easy to see why he’s got that gig, but it does take a deceptive amount of skill to make an otherwise archaic, easily-parodied form like the New Yorker cartoon feel contemporary, and McPhail consistently conveys complex ideas in elegant, striking images.

By contrast, In often feels at odds with itself. The artwork and story often fail to support one another; jokes feel shoehorned in or, worse, built to be excerpted and shared. The book is heavy with symbols, most of which—coffee shops, bars, small talk, Nick’s sketch book—represent the exact same thing. McPhail is so eager to establish the social constructs Nick uses to put a safe emotional distance between himself and others, that he ends up making a single point over and over. The things meant to have symbolic weight often double as gag receptacles—a lot of easy, look-at-this-fucking-hipster-type riffs without much meaning beyond the low-hanging joke. So they’re supposed to make you laugh, AND they’re supposed to mean something, but McPhail rarely connects those two purposes. That’s too much weight for a flimsy symbol to bear. Symbols are a valuable tool for one-panel work, but at book length McPhail struggles to turn them into metaphors that evolve, deepen, and flourish in order to sustain the story. The big aesthetic choice occurs at the points when Nick makes emotional breakthroughs and connects with people, and McPhail’s stoic black-and-white sketches give way to a watercolor dreamworld. Of course, Nick’s dream life is nearly as literal as those in his real one.

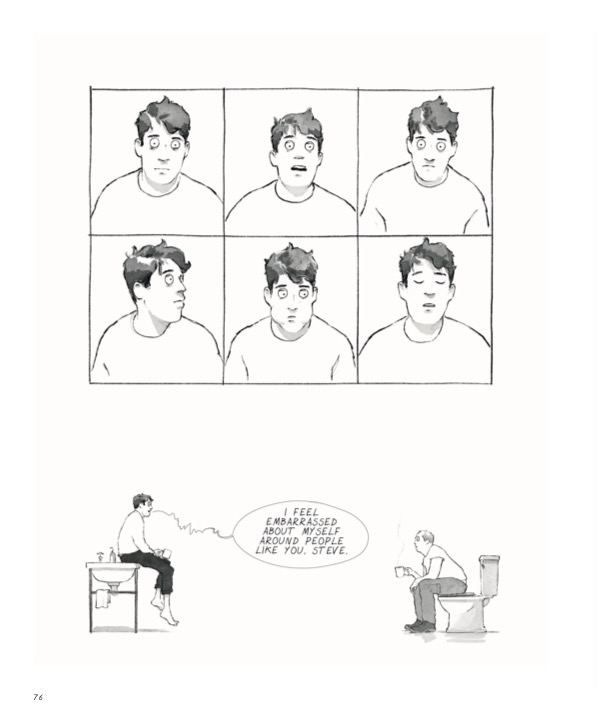

Elsewhere, In runs into storytelling trouble. McPhail draws every character with the exact same range of facial expressions. He seems to be striking a balance between aloofness and caginess, but the result is that characters’ emotional states are consistently inscrutable. Yet In is overly reliant on reaction shots for buttons and punchlines that rarely land. A similar thing happens with some passages, where McPhail might not be communicating what he thinks he’s communicating. At one point, Nick silently helps his mother fix up an old house (incidentally, the one metaphor that McPhail doesn’t belabor, and it’s a cliché). To me, this reads like intimacy: a break in social expectation where Nick can relax and not worry about filling the void with small talk. Later, that passage is revealed to be yet another example of emotional distance.

And yet, despite taking place in a resolutely two-dimensional world, Nick’s story is potent. In is at it’s best when Nick is awkwardly struggling to break through his self-imposed barriers and celebrating even the smallest victory with unrestrained enthusiasm. In one sequence, an honest conversation with his nephew sends Nick to a world where he is crowned King Uncle by a tribe of sentient potatoes. It’s one of the few parts McPhail doesn’t try to make sense of in real time, as well as one of the few places where the author actually seems like he’s having fun. Throughout the book, there’s a sense that writing In has been a way for McPhail to find his own artistic voice through Nick’s story, with Nick, McPhail, and the reader all working together to get through the layers of glibness and deflection and find meaning. Like many first novels, it’s more promising than satisfying. But there are moments, like the sentient potatoes, where it feels like McPhail has found his voice. Hopefully the next project will see him figuring out how to use it.