It would be fair to wonder if, with the advent of the Hilda Netflix series, Luke Pearson might lose a step, stretched thin among projects (less than half the episodes are adapted from the books), but no. Hilda and the Mountain King is maybe less emotionally intense than its predecessor, Hilda and the Stone Forest, with which it makes a pair, but it’s no less visually accomplished or thoughtful. Mountain King picks up right where Stone Forest left off, the earlier work having tormented readers with a cliffhanger of an ending followed by two solid years of waiting for a conclusion. That book was about the way in which parents and children grow apart as kids age into adolescents. They stretch their independence and often the truth as a result. Hilda’s mom is navigating how to loosen the boundaries she’s established while keeping her daughter safe, and their fights are as affecting as anything more mystical or adventuresome. By the end of that book, they’d reconciled and seemed to come to a kind of understanding, and then Hilda woke up as a troll and a baby troll woke up in Hilda’s place. Fade to black.

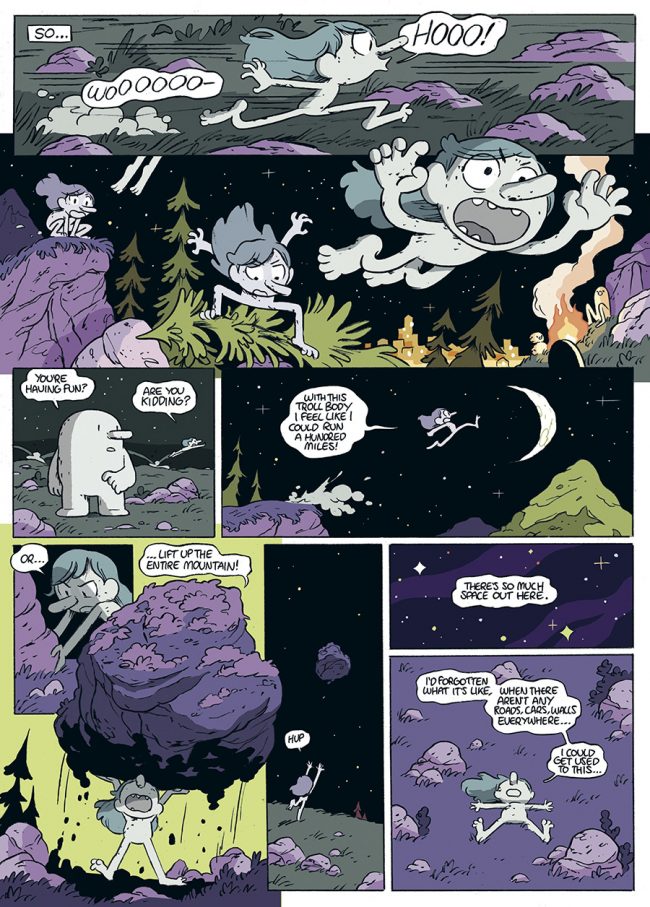

The new book is ostensibly about how to reverse that switcheroo, but that’s just the mechanism for a whole lot of other content. Pearson thinks kids can handle a lot: visually, emotionally, thematically. That’s why they like his work, and why I do too. Simplicity can be a virtue, but there’s also something to be said for embroidery, and he takes just enough from each of those attributes to make strong books. Hilda herself isn’t a perfect heroine. She’s headstrong, hooked on adventure, too apt to think that she knows the right move to make, and it gets her in trouble, but there’s no moralizing about it either. She’s just a person. The panel structure of Mountain King is as visually complex as the range of emotions in the story, and yet neither is hard to read. It feels cinematic without leaving comics behind. There’s no cheap use of Photoshop to blur a background so it feels like things are moving quickly. Instead, he likes to put a bunch of panels on a page, playing with different sizes and shapes. Sometimes he overlaps them, which produces the same impression of speed and action without the cheesy digital effect.

These are big pages (12 inches high by a bit less than 9 inches wide), and Pearson uses them in much the same way that Chris Ware does, tucking things into the corners and generally seeming industrious but not cluttered. He can get 13 panels on a page without you feeling like you’re in an episode of Hoarders. Two-page spreads are even more of a delight, as with a wonderful wordless action scene that opens the book: a large panel that crosses both pages across the top of regular-size Hilda fleeing a giant troll, all of whom we can see is a foot and part of a hand. She zips around a corner, runs up some stairs, promptly runs into another troll, hops off the side of the stairs, slides down the mountain a bit, lands right on top of yet another troll’s head, then skips across the domes of five more (these in a single panel). She’s nabbed in a fist, jerked backwards through the air, glared at, frozen with fear, and then set down, unharmed. She does nothing for a single panel, pondering her fate, then skedaddles off again, slightly less frightened but still in a hurry. The action lines are spare, and we always know right where we are and how we’re feeling. Could he maintain this pace over a book longer than about 80 pages? It’s hard to say. This length feels perfect.

These are big pages (12 inches high by a bit less than 9 inches wide), and Pearson uses them in much the same way that Chris Ware does, tucking things into the corners and generally seeming industrious but not cluttered. He can get 13 panels on a page without you feeling like you’re in an episode of Hoarders. Two-page spreads are even more of a delight, as with a wonderful wordless action scene that opens the book: a large panel that crosses both pages across the top of regular-size Hilda fleeing a giant troll, all of whom we can see is a foot and part of a hand. She zips around a corner, runs up some stairs, promptly runs into another troll, hops off the side of the stairs, slides down the mountain a bit, lands right on top of yet another troll’s head, then skips across the domes of five more (these in a single panel). She’s nabbed in a fist, jerked backwards through the air, glared at, frozen with fear, and then set down, unharmed. She does nothing for a single panel, pondering her fate, then skedaddles off again, slightly less frightened but still in a hurry. The action lines are spare, and we always know right where we are and how we’re feeling. Could he maintain this pace over a book longer than about 80 pages? It’s hard to say. This length feels perfect.

Those panels are neat, but they always feel hand-drawn. If you look at them carefully, you can see that the corners don’t always meet, or sometimes the lines overlap a little. It’s clearly important that things feel real, not mechanical, especially as part of this Scandinavian wonderworld Pearson has created, a simpler place with a lot of outdoor play, a kind of fantasy for Waldorf-type parents. He manages to use a lot of different color palettes. The troll world, which we mostly see at night, is cooler: grays, greens, blues, browns, a bit of yellow, occasionally a rich purple. The human world, in the light of day, uses red, peach, brighter shades of blue, and some orange. When the two collide, the colors merge, but their flatness makes it feel like a unified whole.

Mild spoiler alert here: The theme of parenting continues in this book from the last one, although maybe it’s subtler. It’s a book about nonviolence, to be sure, and about the futility of walls and the need for everyone to learn to trust each other and get along, but it’s also about how parents have to remove themselves to a distance as their children age. They can still watch, but if they try to protect them too much, they’ll wreck everything. Mostly, they have to grant those children their independence and trust that the bond forged early will remain.

Mild spoiler alert here: The theme of parenting continues in this book from the last one, although maybe it’s subtler. It’s a book about nonviolence, to be sure, and about the futility of walls and the need for everyone to learn to trust each other and get along, but it’s also about how parents have to remove themselves to a distance as their children age. They can still watch, but if they try to protect them too much, they’ll wreck everything. Mostly, they have to grant those children their independence and trust that the bond forged early will remain.