While I’ve long championed Masaaki Yuasa as one of the most singular voices in animation, I was less taken with his Devilman Crybaby than the mass of critics. Like all Yuasa series it was an undeniable joy to watch, a kaleidoscope of avant-garde animation techniques, brilliant color design, and dizzying cuts; it was also a complete slog to sit through. Gone were the well-observed character studies and deep warmth that characterized earlier Yuasa works, replaced wholesale by a middle-brow treatise on the seeming-apocalyptic horrors of puberty, the evils of sanctimonious prejudice, and the saving grace of love that papered over its shallow philosophizing with grandiose but vapid Biblical imagery and muddled plotting that left the series feeling more like a clip-show than a fully-realized story. It was sophomoric in the extreme, an attribute I was happy to ascribe as much to Go Nagai, author of the original Devilman manga, as to Yuasa or series writer Ichiro Okouchi.

That a glut of YouTube pedants masquerading as critics and hordes of gatekeeping beardos emerged in Crybaby’s wake to explain how Yuasa’s adaptation owed its depth and power to Nagai’s original Devilman manga only confirmed my suspicions. Nagai is after all the overgrown child best known for penning super-robot slugfests like Mazinger and impossibly horny magical girl series like Cutie Honey, a schlockmeister who mistakes wrathful rants about justice and peace delivered over tableaus of splatterhouse gore for the stuff of great insight and sexual comedy so crass it borders on the misogynistic for satire; it seemed telling to me that his most stalwart fans would defend what was dullest and ugliest in Crybaby as the product of Nagai’s genius alone.

What’s most striking upon actually reading the first half of the original Devilman (available in English for the first time in three decades after publisher Seven Seas fished it from the licensing hell Glenn Danzig’s vanity press Verotik's brutal mishandling once stranded it in; the second half will follow in October) is how wrong everyone – not just the fans, not just myself, but Yuasa and Okouchi, as well – got it. To be sure, Devilman IS a crass work, every bit as stupid and preachy and ugly as the worst elements of its adaptation and defenders would suggest. The major plot points are much the same: Fudo Akira is still the spineless wretch who gives his body and soul to the demon Amon so that he might gain the power and courage necessary to fight off the waking demon hordes that seek to reclaim the Earth they long ago abandoned; friend and partner Ryo is still the comically sociopathic aristocrat who espouses goals that sound altruistic in theory but suggest more sinister designs in practice. Nagai might hope the reader would blanch at Ryo’s callous slaughtering of a band of revelers he recruited in a ploy to draw out demons, but he plays this and other story beats with such over-the-top abandon that they come across less as serious commentary on the evil that lurks in the heart of men the characters’ grave monologues suggest than as the stuff of absurdist comedy. How else could readers interpret a series where characters deliver stentorian exposition about the coming extinction of humanity while wearing massive bug masks that transmit ancient history into their heads? Where demons sneak back in the middle of the night to repair the holes they left in Akira’s roof to “keep humanity ignorant of their existence?” Where our heroes inexplicably find themselves hopping through time to battle a rifle toting Nike in ancient Greece or the demon that stoked Hitler’s anti-semitism by kidnapping his lover? It’s no accident that Devilman was most familiar to Western readers for years as that manga where characters snidely remarked that their cigarettes were “laced with drugs.” Nor is it any mistake that Yuasa and Okouchi took such pains to excise the most ridiculous of Nagai’s indulgences while burnishing instead those elements they perceived to be the core of Devilman’s appeal.

What’s most striking upon actually reading the first half of the original Devilman (available in English for the first time in three decades after publisher Seven Seas fished it from the licensing hell Glenn Danzig’s vanity press Verotik's brutal mishandling once stranded it in; the second half will follow in October) is how wrong everyone – not just the fans, not just myself, but Yuasa and Okouchi, as well – got it. To be sure, Devilman IS a crass work, every bit as stupid and preachy and ugly as the worst elements of its adaptation and defenders would suggest. The major plot points are much the same: Fudo Akira is still the spineless wretch who gives his body and soul to the demon Amon so that he might gain the power and courage necessary to fight off the waking demon hordes that seek to reclaim the Earth they long ago abandoned; friend and partner Ryo is still the comically sociopathic aristocrat who espouses goals that sound altruistic in theory but suggest more sinister designs in practice. Nagai might hope the reader would blanch at Ryo’s callous slaughtering of a band of revelers he recruited in a ploy to draw out demons, but he plays this and other story beats with such over-the-top abandon that they come across less as serious commentary on the evil that lurks in the heart of men the characters’ grave monologues suggest than as the stuff of absurdist comedy. How else could readers interpret a series where characters deliver stentorian exposition about the coming extinction of humanity while wearing massive bug masks that transmit ancient history into their heads? Where demons sneak back in the middle of the night to repair the holes they left in Akira’s roof to “keep humanity ignorant of their existence?” Where our heroes inexplicably find themselves hopping through time to battle a rifle toting Nike in ancient Greece or the demon that stoked Hitler’s anti-semitism by kidnapping his lover? It’s no accident that Devilman was most familiar to Western readers for years as that manga where characters snidely remarked that their cigarettes were “laced with drugs.” Nor is it any mistake that Yuasa and Okouchi took such pains to excise the most ridiculous of Nagai’s indulgences while burnishing instead those elements they perceived to be the core of Devilman’s appeal.

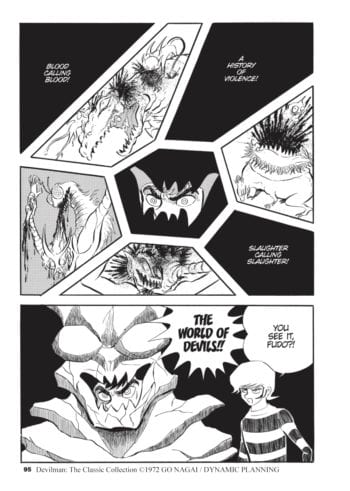

Similarly obvious is why Yuasa’s superflat and whimsical art shouldered out Nagai’s more grindhouse stylings: Devilman’s aesthetics are every bit as clumsy as its writing. The hosts of hell sound terrifying when kept to the shadows; as a parade of buxom harpies with tentacles trailing out of their tits and with teeth where their vagina should be they seem more like on-the-nose manifestations of the author’s comic insecurities about female sexuality. Human characters fare little better, their bodies and faces often appearing molded from melting plastic: it often looks as if everyone and everything were once normally proportioned toys a child had subjected to a full-blast oven. EVERY element of the comic feels like something a child would concoct in a sandbox as they narrated in stentorian tones the crashing and bashing together of their action figures.

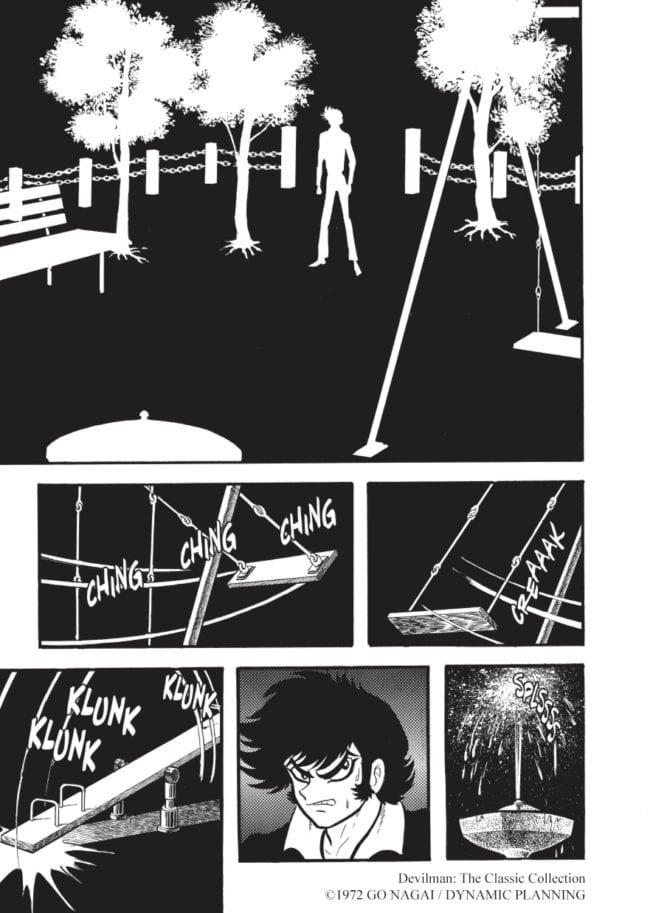

Yet it is exactly this amateurishness that prevents Devilman from ever devolving into the complete bore its spin-offs, imitators, and spiritual kin are so apt to become. Nagai is unfettered by good taste and the strictures of competent storytelling and so feels no shame in airing even his strangest proclivities or following counter intuitive paths which in turn allows him to channel energies and images and scenarios more professional artists would shy away from. For all that these pages are a mess they are also possessed by an urgency that elevates them from mere historical curiosity or ironic laugh-fest to something worthy of earnest attention. Yes, the bizarre subplots that find Akira saving Joan of Arc from a kangaroo court in hell or ripping a demon from Marie Antoinette’s skull are tonally messy and stupid in the extreme. They are also absurdly compelling precisely because they lack any kind of self-consciousness, because they are the expression of an artist grasping unaffectedly towards his own personal truth no matter how asinine they may be. No battle here is as well-defined or choreographed as the apocalyptic brawl between Satan and Amon in Crybaby, but then nothing in Crybaby feels as brutal or visceral or so demanding as the climactic confrontation between Sirene and Akira in this volume, clumsy paneling be damned. Yuasa’s most virtuosic display of animation genius seems like so much self-indulgent noodling compared to Nagai’s dramatic use of white silhouettes against stark black backgrounds that lend this volume’s goofy attempts at horror an undeniable atmosphere of dread they do not otherwise deserve. Even the showdown with soul-stealing turtle Jinmen feels more disturbing here than in Crybaby despite being given none of the time to breathe or emotional ballast that lent Crybaby one of its few truly shaking scenes.

Yet it is exactly this amateurishness that prevents Devilman from ever devolving into the complete bore its spin-offs, imitators, and spiritual kin are so apt to become. Nagai is unfettered by good taste and the strictures of competent storytelling and so feels no shame in airing even his strangest proclivities or following counter intuitive paths which in turn allows him to channel energies and images and scenarios more professional artists would shy away from. For all that these pages are a mess they are also possessed by an urgency that elevates them from mere historical curiosity or ironic laugh-fest to something worthy of earnest attention. Yes, the bizarre subplots that find Akira saving Joan of Arc from a kangaroo court in hell or ripping a demon from Marie Antoinette’s skull are tonally messy and stupid in the extreme. They are also absurdly compelling precisely because they lack any kind of self-consciousness, because they are the expression of an artist grasping unaffectedly towards his own personal truth no matter how asinine they may be. No battle here is as well-defined or choreographed as the apocalyptic brawl between Satan and Amon in Crybaby, but then nothing in Crybaby feels as brutal or visceral or so demanding as the climactic confrontation between Sirene and Akira in this volume, clumsy paneling be damned. Yuasa’s most virtuosic display of animation genius seems like so much self-indulgent noodling compared to Nagai’s dramatic use of white silhouettes against stark black backgrounds that lend this volume’s goofy attempts at horror an undeniable atmosphere of dread they do not otherwise deserve. Even the showdown with soul-stealing turtle Jinmen feels more disturbing here than in Crybaby despite being given none of the time to breathe or emotional ballast that lent Crybaby one of its few truly shaking scenes.

Devilman is repellent and stupid, yes, but it is also a certain kind of joyous, the work of an artist who believed deeply in every line he rendered and every emotion he so obviously struggled to portray. By sanding away the roughest edges – by emphasizing what seemed smart and meaningful while banishing what was most obviously ridiculous – fans, critics, and adapters alike missed that the worst in Devilman is precisely its juvenile posturing towards philosophical depth. That what truly lends this work its singular appeal is Nagai’s openly childish voice, a voice that rings as clearly and honestly and compellingly as the voice of a child narrating the apocalyptic confrontations between his armies of action figures.

Devilman is repellent and stupid, yes, but it is also a certain kind of joyous, the work of an artist who believed deeply in every line he rendered and every emotion he so obviously struggled to portray. By sanding away the roughest edges – by emphasizing what seemed smart and meaningful while banishing what was most obviously ridiculous – fans, critics, and adapters alike missed that the worst in Devilman is precisely its juvenile posturing towards philosophical depth. That what truly lends this work its singular appeal is Nagai’s openly childish voice, a voice that rings as clearly and honestly and compellingly as the voice of a child narrating the apocalyptic confrontations between his armies of action figures.