In his introduction to this book, author Jeremy Dauber says that the overall goal of American Comics: A History is to cover “the whole shebang,” everything from 19th century political cartoons to the current rise of the YA graphic novel and all the stuff between. As ideas go, it’s not a bad one. While there have been numerous books chronicling various historical periods, delivery systems or genres–the underground era, comic strips, superheroes–there hasn’t, to my knowledge, been a book that tries to incorporate all of American comics history.

Dauber, a Columbia University professor, does meet that objective, but the real question is whether he provides an enlightening and well-rounded look at the medium along the way. The answer, unfortunately, is a shrugging “sometimes.”

To his credit, Dauber doesn’t rely on the overly-familiar and inaccurate clichés of the Yellow Kid starting everything, etc. He begins instead with Rodolphe Töpffer and the bootleg copies of his work that appeared on U.S. shores in the mid-19th century. (The bibliography shows he’s done his research, citing everyone from David Kunzle to Tom Spurgeon and what appears to be almost every issue of The Comics Journal.) From there he goes to Thomas Nast, segueing to the birth of newspaper comic strips and then following a somewhat predictable path from early comic books to E.C., and then the undergrounds and so on. Thankfully, Dauber has a light, conversational style that keeps the book from becoming a slog.

But all too often the book feels like little more than a checklist. As the decades progress and more and more titles and authors crop up, Dauber devotes a few tossed-off acknowledgments to comic after comic, lest he be accused of forgetting someone really important - or worse, someone’s favorite. Toward the end of the book it feels at times like he’s just shouting one title after another to the wearied reader. Have you heard of Salamander Dream? Picnic Ruined? Filthy? The Squirrel Mother? Underwater? Oddville!?

This can not only be dizzying but frustrating, given what Dauber chooses to highlight and what he glosses over. It’s great, for example, that Dori Seda is given her due, but also confounding that Julie Doucet is passed over so quickly, to say nothing of the short shrift Jim Woodring is given. And considering his influence on contemporary cartoonists, it’s a bit shocking that John Stanley receives only two sentences, mainly as a reference to Little Lulu creator Marjorie Henderson Buell. What’s more, considering the breakneck pace he sets for himself, it is odd the moments where Dauber does take time to delve. Why, for example, spend two full pages on EC’s A Moon, a Girl... Romance? Surely there are better ways to highlight the romance comic trend while segueing into Bill Gaines and company?

Dauber also brings up intriguing points without exploring them. In chapter 4, “From Censorship to Camp”, he notes how the rise of MAD magazine, along with Feiffer’s Village Voice strips, Pogo and Peanuts, aligned with the rise of stand-up comedy from folks like Mort Sahl and Lenny Bruce, moving mainstream comics away from slapstick and vaudeville-styled humor to more emotionally and politically resonant material. It’s a comparison I haven’t seen made too often, but Dauber drops the idea as soon as he gets it on the page in order to keep the train moving.

There are also errors. Sometimes sloppy, easily correctable ones. He says, for example, that both Krazy Kat and Ignatz shift genders (no, it’s just Krazy). He says Robert Crumb “concluded” Zap Comix “for good” in 1998, but issues came out in 2005 and 2014, both of which featured work from Crumb.

Often it’s not inaccuracies so much as odd sins of omission, or at least poor phrasing. His description of the Air Pirates debacle makes it sound like it was all Dan O'Neill’s doing and didn’t involve other artists (he leaves that information for a footnote). Yes, Panic was E.C.’s own knockoff of MAD, but Dauber’s phrasing makes it sound like it was all done in good fun, when it’s known that MAD editor Harvey Kurtzman was less than pleased about a derivative title competing for E.C.'s artists. Dauber's wording can also easily lead to confusion for a reader unfamiliar with the pop culture landscape. For instance, in talking about diverse casting in superhero films, he includes a quote from James Gunn that makes it sound like Gunn was the director of Spider-Man: Homecoming (spoiler: he wasn’t). Maddeningly, Dauber also plays a shell game with names, titles and dates. At one point he might mention the author and date of a particular comic but not the title. Then, a few sentences later, he might mention the title and date but not the author.

And while Dauber can turn the occasional clever or insightful phrase (“Watchmen is a superhero story in much the same way Moby-Dick is a treatise on the New England whaling industry”), he seems to struggle in trying to describe the art itself, the very thing that drives the narrative in comics.

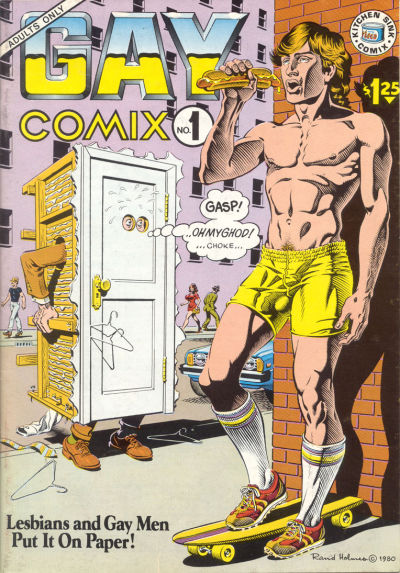

There are highlights. Dauber does a good job chronicling the nascent gay movement in underground and alternative comics. He also does well navigating the various initial forays into online comics in the early '00s and the quirky Garfield Minus Garfield-type offshoots that cropped up. And it should be mentioned that he frequently takes great pains to note the painful racist and sexist attitudes in older works while highlighting the pioneering outliers that attempted to provide a voice for minorities and women.

But for all his efforts to make sure everything gets its due, there are genres ignored or glossed over. Editorial cartooning is just plain missing (with the exception of Nast), and gag cartoonists are barely mentioned - hardly a glance to the New Yorker crew. Comic strips are dropped like a hot potato as soon as periodicals enter the fray, save for the occasional nod to cultural movers like Doonesbury, Bloom County or Calvin and Hobbes. It’s understandable that Dauber wouldn’t want to put too much focus on the newspaper side of things, but one can’t help but feel that it’s an area that deserved more exploration than is given here.

Honestly, I’m not sure who is the ideal audience for this book. Fans and scholars will be frustrated by its checklist nature, odd phrasings and slip-ups. Neophytes and more casual comics readers will likely walk away from it a bit disoriented by the deluge of names and titles, thinking little more than “gosh, there sure are a lot of comics out there.”

Perhaps my biggest problem with American Comics: A History is there’s too much advocacy and far too little analysis and criticism. While Dauber does often note the ill treatment that many cartoonists have labored under since the early days, he doesn’t hammer that point home hard enough to suit me. In an age where comics have gained a form of respect (if arguably meager), or at least are seen as a springboard for other mediums, the constant struggles–not just for legitimacy but for financial solvency–remain. Creators' rights are still an issue in 2022. And while an artist could once make a living selling work to magazines or via a strip, being able to pay the bills seems more and more like a pipe dream, book deal or no book deal.

This to me, is a central thread of comics history in North America, and should have been the focus of Dauber’s book. Instead it’s a side note - cause for concern, perhaps, but nothing that would distract you too much from the shiny brochure.