What’s this - Peter Milligan, you say? Always something new on the grill from Mr. Milligan! Why, just in the last little while I’ve brought home new chapters of his periodic mutant saga The X-Cellent, with Mike Allred - two recent miniseries of five issues each, one in 2022 and the next in 2023. Who could have guessed they’d still be spinning out permutations of that original, brilliant run on X-Force 22 years ago? Another highlight: Absolution, five issues across 2022, from AWA with Mike Deodato on art. Near-future ultraviolent sci-fi media satire, total Paul Verhoeven hours. The book that pushed Deodato back on my radar.

But we’re not here to talk about anything new. No, we’re here on old business, in the form of a timely reprint. Like that Glen Dakin book I looked at a few weeks back, it's a reissue of selected older material in pamphlet form. The superhero companies are making quite a bit of hay on facsimile editions of older comics, recently, and while this isn’t quite that, it’s nevertheless very close to the impulse. Really flattering package, truth be told. The pamphlet is a gratifying format, aesthetically pleasing in an irreducible way. Nice to be reminded. We haven’t quite managed to kick it, for a good reason. Maybe we’ll see more projects in this vein.

The present volume collects two vintage Milligan rarities, both with longtime collaborator Brett Ewins: "Rooney’s Lay" from 1980 and "In the Penal Colony" from 1991. According to a convenient timeline in the back of the book, Rooney’s Lay, initially published in Magnetic Fieldz Magazine #2, represents the first collaboration between Milligan and Ewins, with their adaptation of the Kafka story (from A1 #5) coming after a solid decade of work together on everything from Tharg’s Future Shocks through to Johnny Nemo (from Strange Days and Deadline, plus an eponymous Eclipse miniseries) and Bad Company (from 2000 AD). They did Skreemer together with Steve Dillon for DC, and even managed to put out a Mister X Special in 1990 - rarified company, that franchise. There aren’t otherwise a lot of vertices between the 2000 AD crew and Los Bros Hernandez.

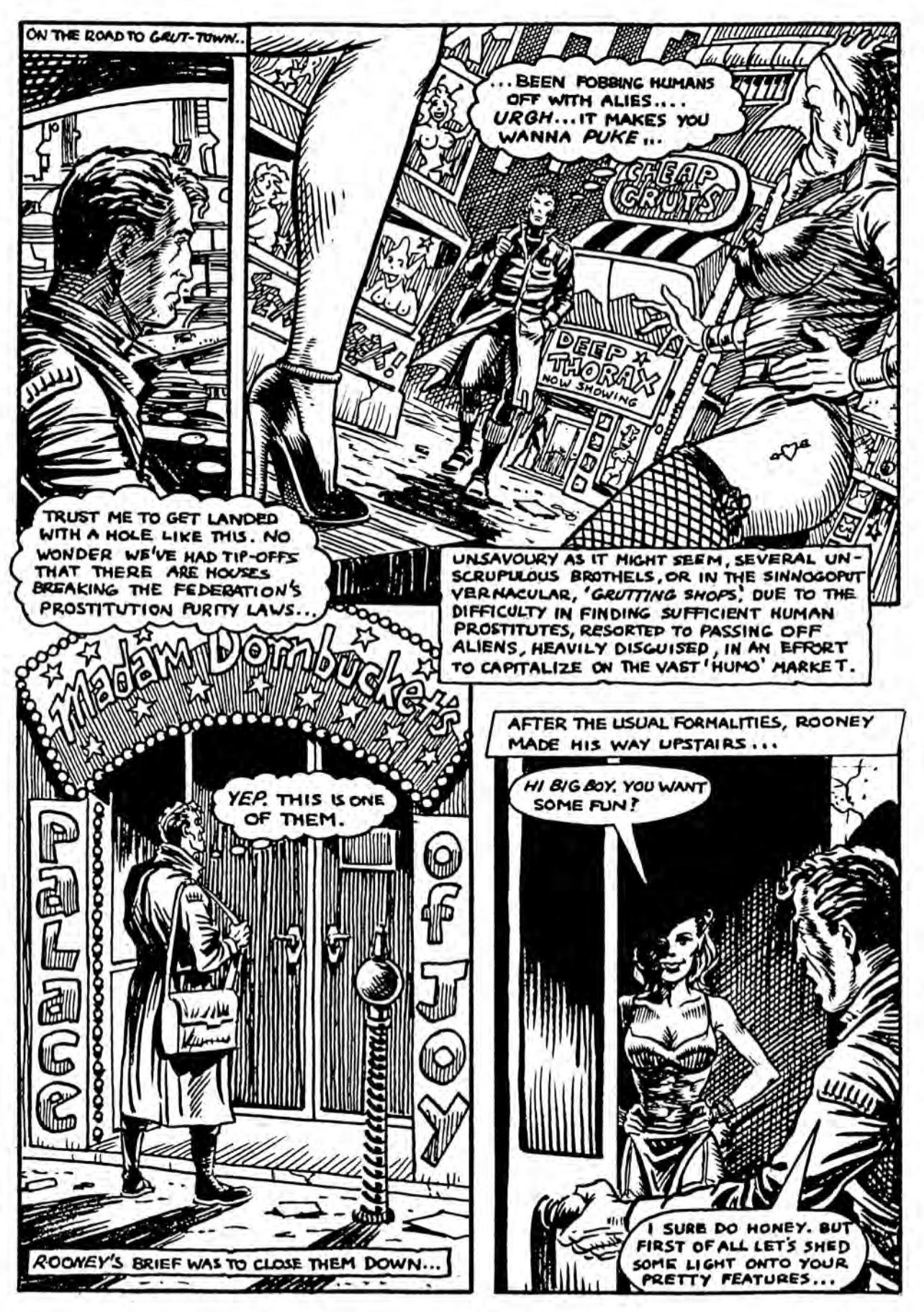

"Rooney’s Lay" is precisely what you’d expect from a 19-year old writer fully in thrall to Philip K. Dick - scabrous and obscene, yes, but also pointedly topical. As far as juvenilia goes, it’s actually quite a well-done story: a space bigot rejects alien prostitutes down the line, until he meets one who scrambles his brain into permanent devotion. It’s about as fraught as you’d expect a story about interstellar sex workers written by a teenager to be, but nothing worse than eye-rolling. Just desserts for the bigot, one supposes. Could be a lot worse! It’s a short piece, no need to belabor the point, but clearly an important work for the duo.

It’s the adaptation of Franz Kafka’s 1919 “In the Penal Colony” that will probably attract more attention here, if we’re being frank. It’s a good adaptation of a great story. Less a straight adaptation and more an adaptation in the art with a personal commentary in the text - the story begins, “When I was young I fancied myself somewhat Kafkaesque,” which is about the best description of a certain kind of insufferable youth imaginable. Thankfully I didn’t get around to Kafka until my 20s. Not a young man’s writer - or at least, for the sake of our young men, hopefully not! Young men deserve healthier role models, like Goethe.

“In the Penal Colony” is rightfully one of the more famous stories by one of the defining writers of the 20th century, and Milligan is hardly the first reader to find themselves so fascinated. Kafka didn’t write horror, per se, even as most of what he touched was by lengths somewhere on the spectrum between morbid and macabre. “In the Penal Colony,” however is about as close as he got to straight horror, with a central image straight out of some manner of 1980s splatterpunk anthology. That’s the core of it, really - that idea of being tortured to death by a machine as some manner of romantic transformation: torture as a means to see beyond the veil of Maya. Very much like something you’d expect to see in the Books of Blood.

And this is where Ewins really distinguishes himself. There’s a full page devoted to an illustration of “the apparatus” - the torture machine at the heart of the story, and surely one of the most fascinating such machines in literary history. “Brutal but... offering some shape and sense to his brutal world,” as the narration tells us. Ewins does a great job with a machine of almost Lovecraftian ambiguity, all pistons and concentric cogs, a device to translate the ineffable reality of authoritarian control onto the ultimate canvas of human flesh. Ewins’ version of the machine is futuristic in the context, a mass of gleaming and ineffable comic book tech. If Reed Richards designed a torture machine it might look something like this.

The story retains its magnetic fascination precisely because it is brutally fixated on conditions of reflexive institutional sadism that remain so very current. “In the Penal Colony” is 104 years old, and one certainly wishes we could look back through Kafka’s lens and see the old boy was needlessly worried. Alas! He had a bead on the century to follow, he certainly did.

“I don’t know why In the Penal Colony held a special appeal to me,” the narration confides toward the end of the story. “Maybe because at its core it seemed to mean absolutely nothing.” That strikes me as very much the kind of thing a 30-year old would write, as Milligan was 30 when that story saw print. “In the Penal Colony” doesn’t mean nothing, and I don’t even think Milligan thought that when he wrote those words. It means too much - has become in the fulness of time too prescient to be adequately summarized. That’s the real terror, and it’s hard not to see how any young and impressionable reader might not be waylaid by such a writ of prophecy.

But then, Milligan has always been a thoughtful writer, brimming with ideas. He never really developed the slight maudlin edge that Gaiman can wield to sledgehammer effect, and eschewed the high formalism that Moore found so effective. Always maintained just a bit of ironic remove, without so much of the animating sentimentality of his peers. Among the second wave of “British Invasion” writers he is the one most likely to be underestimated, but look and you'll see a spotless record stretching back to the days of Thatcher. Deserves significantly more in the way of retrospective than this review can provide.

Sadly, his companion for these pieces, Mr. Ewins, passed away in 2015. His work with Milligan, in a number of different genres and venues, was imaginative and crisp, never less than interesting, and sometimes—as in this issue's “In the Penal Colony"—capable of sublime heights. These two stories have been padded out in the present volume by an interview with Milligan on the circumstances of the extended collaboration: “I felt a certain part of me,” he says, “a part of me that wanted to explore a particular mood or certain themes, naturally came out with Brett.” The evidence presented here would certainly seem to attest to the strength of the combination.