This is a beautiful book, though let the use of the "Surreal" in the subtitle be a warning - it is not always easy to understand. Its opening page is a full portrait of Leonora Carrington (1917-2011) surrounded by mystical figures, an intensity in her eyes, hands cupping an egg, while she claims that she’s “mostly a horse... but sometimes a hyena,” and also that her mother “was away at the time” of her birth. These are quotes from the lady herself, an incredibly interesting figure in not only the greater context of the Surrealist movement, but also as a painter, writer and feminist in her own right. It does help to have some foreknowledge of the woman going into this book. An early 'hyena' vignette is lifted straight out of Carrington’s short story "The Debutante." And Leonora will often be shown morphing into both of those creatures, the hyena and the horse, as the splash pages multiply throughout. Lovely work too, depicting scenes such as her introductory experience at the London International Surrealist Exhibition in 1936–heart ablaze, whole body levitating at the magic of what was on offer–or engaged in astral animal sex with Max Ernst, him a bird, her ever an equine. Such transformation was not all that much a stretch to Ms. Carrington - Ernst had a fascination with our feathered friends, and she would paint Bird Superior, Portrait of Max Ernst in 1939. Later we’ll see Leonora communing with horses as she tries to escape the Nazis, much to the chagrin of her companions.

Obviously, Carrington as subject matter is tricky stuff. Both her life and work were incomprehensible to most people, even those close to her. Writer Mary Talbot does a good job of balancing biography whilst channeling Carrington’s character, presenting the narrative as coherently as she can while also letting loose the artist’s wild spirit. The text itself can’t help but be surreal, morphing and changing and coming across as odd even as straight fact is quoted. But the major points of her life are all here: from being an obstinate, willful child–qualities she will never surrender–at the home of her rich English parents; through her bohemian life on the continent until it was upended by the war; through to her final exiles in New York and Mexico City. All of this flows with a chaotic pulse. All, that is, except for hers and Ernst’s time in the French countryside of Ardèche. This interlude drags compared to the rest. It is necessary to be shown, if one is being true to her life, and will come into play later on as complications arise with the German Ernst's presence in wartime pre-occupation France. But even with Max’s wife entering the picture, these pages come across as somewhat dull. And perhaps the events they depict were. It seems to have been the only quiet time in her life, bar her last days in Mexico.

At times there is some confusion on the page in these quiet moments. On page 59 (above), two women argue in front of a canvas, both of whom could pass as Leonora Carrington. Indeed, one even addresses the other as "Leonor." It is only through much flipping back and forth through the pages that one realizes this is mean to be the painter Leonor Fini, who had briefly appeared in two panels on page 41 right before the introduction of Peggy Guggenheim, and is seen on page 59 with a different hairstyle. There are five pages of Notes at the back of the book, though no entry for page 41. The note for page 45 mentions a chapter on "The Two Leonors" in a reference text, but declines to shed any light on the actual scene in this book. And Page 59’s note mentions “Leonora’s acute awareness of her declining mental state.” A simple inclusion of the Fini surname would have sufficed to avoid the questions arising about any sort of split personality in Carrington herself. As it is, one is taken out of the text, at its slowest point as well, to try and figure this out. Things are further muddled when dozens of pages later, on pg. 125 (below), Remedios Varo, with similar short hair to Leonor Fini, comes back into Carrington’s life after having only been seen for a moment, years before, at that same first Guggenheim visit.

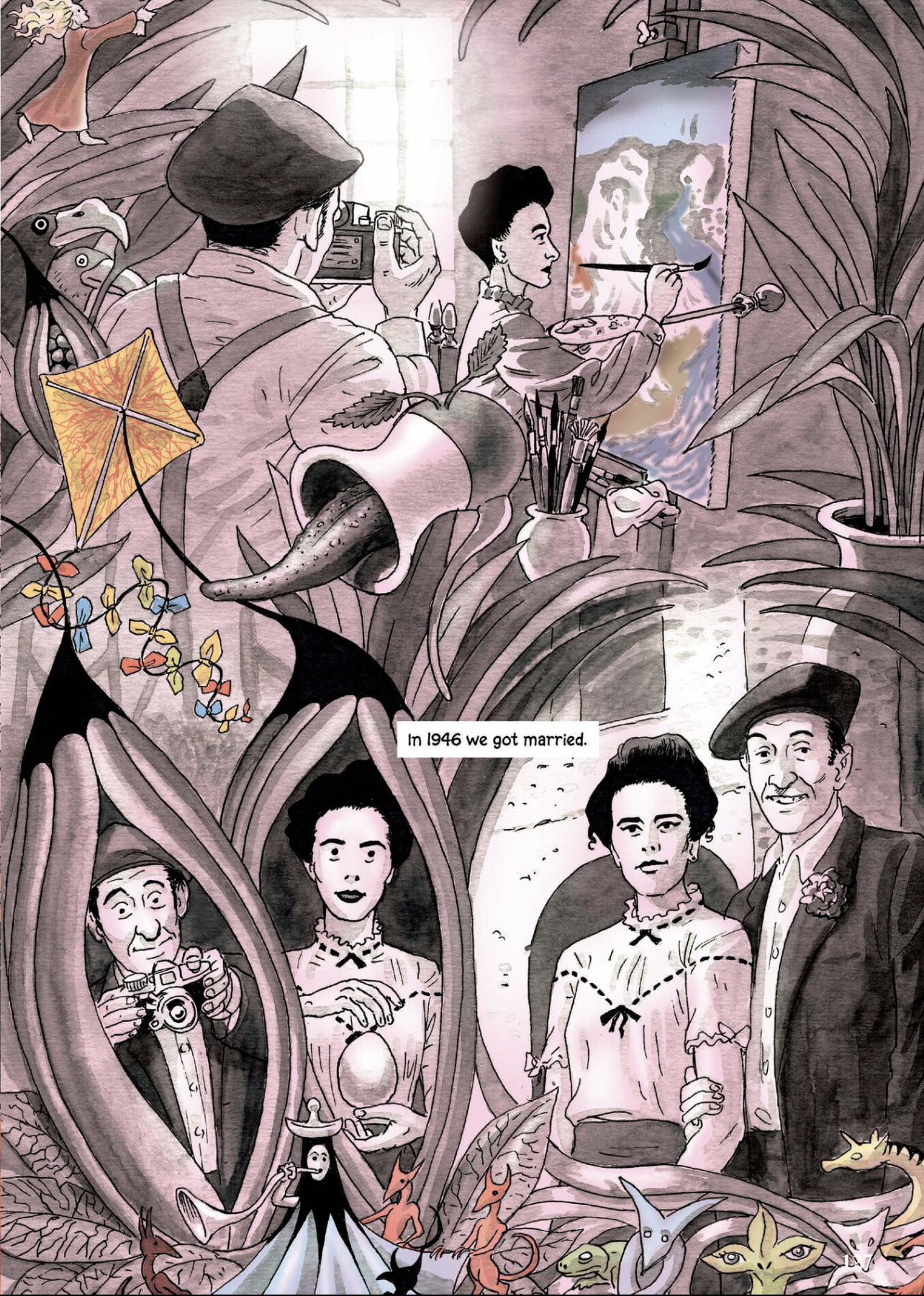

All in all though, this is a lovely little book. The only other quibble comes from its actual size. With the incredible artwork inside, and so much going on on each page, it would have benefited from being larger than its 6.5" x 9" dimensions. And the art really is something to behold. Bryan Talbot’s detailed penwork is presented in sepia tones, and covered with a large variety of enhancing, dreamy color washes. On page 126 the color pink tints the scene where her future husband, Emerico "Chiki" Weisz, hands her a rose as she holds another egg, while orange lays over the surreal landscape on the bottom, inspired by two of her paintings, The House Opposite and Chiki, ton pays (Chiki, Your Country). It is satisfying to catch sight of Carrington’s own works within these pages, and they are rendered so well, such as when she is painting "Bird Superior, Portrait of Max Ernst" on page 65, which is also seen at a more obscured angle on the cover. To help spot the references, including those springing from her literary works, one can check the Notes, though Bryan Talbot does a wonderful job–as dreams do, as life does–of blending many different aspects of a scene together into the multi-faceted yet concise whole of a single page. Armed With Madness is a visual treat; even just flipping through the pages at random one can’t help but be struck by its beauty.

Besides all the crazed creativity, there is also humor, kindness and love within these pages. The book ends with an aged Carrington surrounded by admiring young fans, thankful for all she contributed to Women’s lib. She answers their questions and offers some wise advice. Her playful nature is especially seen on the final page, through words of wisdom paraphrased from her novel The Hearing Trumpet: “People under seventy and over seven are very unreliable, especially if they’re not cats.” In these final pages Carrington is quite lucid, as well she may be, according to her own dictums, close to her death at age 94. The Talbots do an excellent job at fitting all that life into 144 pages.