One fine day an email appeared from my editor, asking if I remembered Glenn Dakin. “Why, that old salt?” I roared into an empty room. Of course I remember Glenn Dakin! How could I ever forget the co-creator of Die-Cut? Why, I remember as if it were yesterday: Czorn Yson was a mutant from the planet Ganalus, see, whose special ability was cutting through time and space with a giant razor. He fought Death’s Head II - not the one people like, but the other one, who confused people.

Now, funny thing about the Glenn Dakin who wrote a few books for Marvel’s late, lamented UK office during the heady days of the early 1990s: he also produced a significant body of work as an autobiographical cartoonist, in the vein of similar work by a longtime friend of his, Mr. Eddie Campbell. I believe I said a few words about Campbell recently in these august pages. Sadly, for all his plaudits, Campbell never got to write anything for Marvel UK. He’s still alive, so there’s still plenty of time for him to deliver unto us the definitive Motormouth story - with or without Killpower, I’ll leave that up to him.

Perhaps you recall a collection that hit our fair shores roundabout 2002 - Abe: Wrong for All the Right Reasons, released by Top Shelf. I also reviewed that book, back in the day, for a website that no longer exists. I have reviewed many books for websites that no longer exist, and even a couple websites that continue to shamble down the road as zombie SEO bait. Imagine then my surprise, upon checking up on Dakin’s recent movements, to find him a prolific author of various titles such as Be More Batman and Mr. Spock’s Little Book of Mindfulness - cute little volumes of nerd lore aimed at general audiences. Stocking stuffers.

Dakin has a new collection out, but not of new material - A Trial Death and Other Stories, from Colossive Press, features “Abe” stories from the '80s and '90s in a tiny little (as in slim, 28-page; in size it is 8.3” x 11.7”) pamphlet with a sharp-looking Riso cover. What’s the occasion for this sudden turn down memory lane? I couldn’t hazard a guess, and the promotional material leaves me none the wiser. Perhaps enough to say that this volume appears, now, because it should. Any later would be too late, and now is better than never.

The title feature is a three-page story from 1994, detailing a depressive episode from the previous winter. The author—or rather, the pseudonymous “Abe”—has suffered the kind of merciless season that assails us all on occasion. “When those November nights came down,” he relates, “I felt as if my soul was between the hammer and the anvil.” We are given a little doodle of Abe’s head being flatted by an imposing Mjolnir, accompanied by two ringing musical notes. “Little things and big things went wrong. People that I like were sad - and people I dislike advanced in the world and lost their sanity.” Surely the most relatable of sensation, in these spiritually lean years. What is it that finally turns the truck around? “Someone writes a nice article about the comics I did a few years back.” The sensation of hearing an advance preview of his own elegy knocks him out of his funk. Do you see now how powerful and influential comic book critics can be?

Dakin’s line here is quite gratifying. He shares with Campbell that same commitment to the seemingly tossed-off, the casual brushstroke that appears in places as much a species of squib as a deliberate mark. There’s a similar feel to later Feiffer here, casual at first glance but in fact quite precise. The line goes where it needs to go, no more and no less. Look at “A Song of Spring,” from all the way back in 1985. A bit more fussy than some of the later work, no doubt. Every frame in these nine-panel grids depicts a different scene, or scenery. Sitting in a train or walking along the park, mulling around a pub, all very quotidian - and then, at the end of the sequence, three panels of walking through Cambridge on a dark night defined by careful shadows, architectural specificity in breathtaking, minuscule chiaroscuro. My goodness.

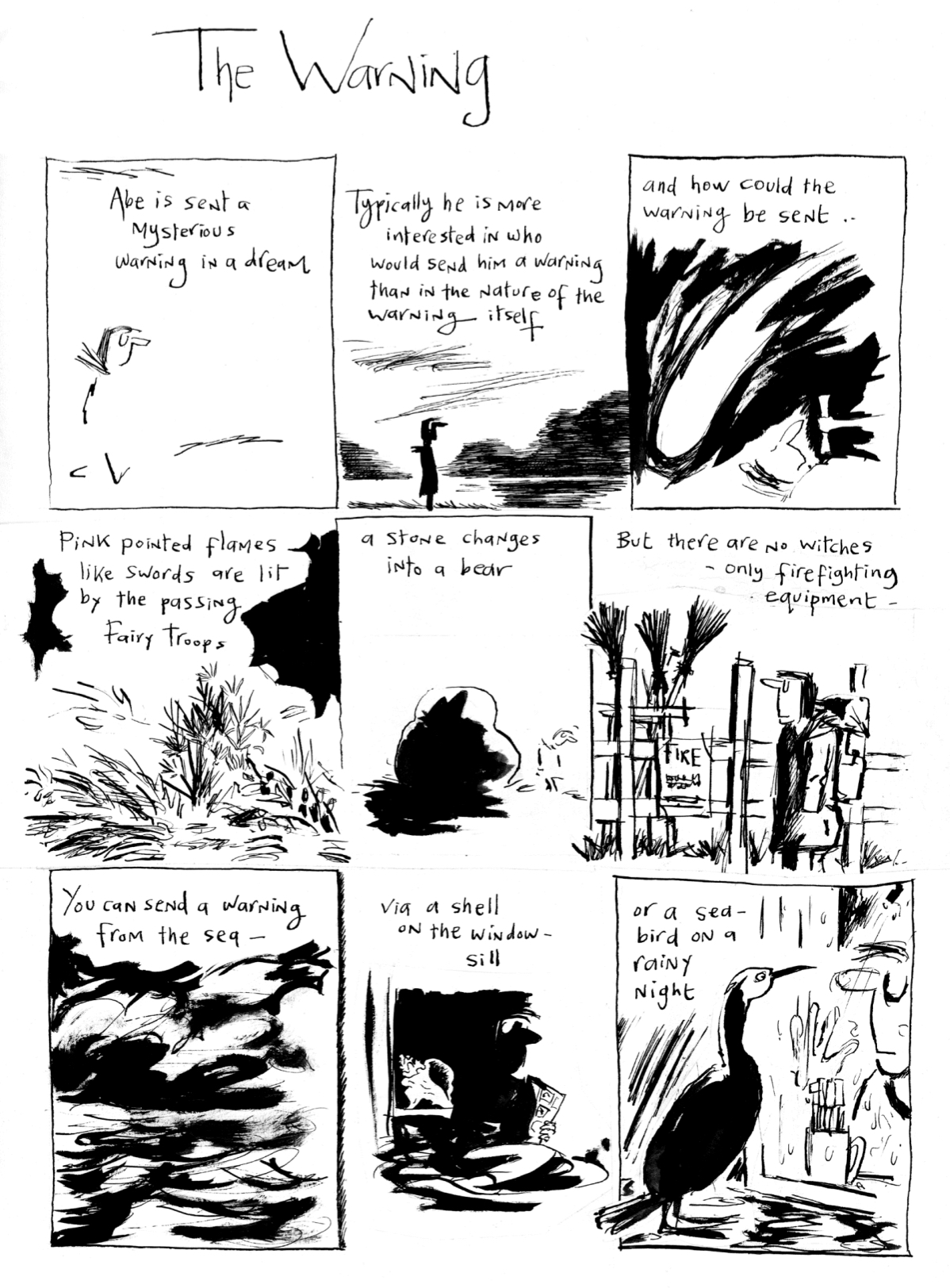

I quite like the little smudge of black ink surrounding a drawing of the moon on the next page, for “Abe Inherits the Moon,” subtitled “be brave when you leave.” Just a few stabs with the ol’ Winsor Newton, a lovely tactile evocation of the balmy deep of space cradling our dear satellite. Abe’s grandad won the Moon off the King of the Moon People in a card game, and the heir selflessly resists all attempts at commercialization. If you like the way Dakin tosses the ink around the page, check out “The Warning,” a strip about a dream that uses evocative splashes of black to shape unconsciousness as a species of perception regarding shadows. That story showcases Abe in his most classic pose: romantic wanderer seen in profile across the miasmic landscape. He’s breaking things down here, as minimal as he can get while still retaining some degree of mimesis. “A stone changes into a bear,” we are told, and shown the outline of a stone containing a dark splotch with bear-like features. You might even miss the figure of Abe slouching across the background of the panel, twelve or thirteen flicks of the wrist to carve a profile on the page.

If anything about Dakin might grate on the unwary reader, it might be a tendency towards rhapsody that could under uncharitable kliegs be reduced to bromide. He would appear to have been aware of this tendency, to judge from “Not the Sea, the Desert.” (Campbell, in a brief Foreword, tells us this desert is not unlike the Australian expanse across which he and Dakin shared a long journey by train, and now we are left ourselves to imagine the Dionysian wonders of a continental train ride accompanied by Eddie Campbell and Glenn Dakin.) Dakin encounters a wise man who speaks from a rock on high: “Love life - but don’t go around saying ‘Love Life.’ Seek enlightenment but avoid using the world ‘enlightenment.’” Some of the best advice you can get from a comic book, at least one that isn’t showing you how to conduct a necessary self-examination.

The longest story in the book, “We Have All the Time in the World,” clocks in at a weighty six pages. It’s about a holiday in Greece, the kind of delightfully formless and infinitely relaxing vacation in foreign climes that people don’t really get anymore, at least not in the Anglosphere. Seems like the only kind of vacation the kind of people who can afford to take a vacation take anymore are loud and disinterested jaunts, vigorous package tours involving fancy drinks and wristbands. Lazy endless days in exotic locales, absorbing the local life at its own speed... like a luxury from the days of Trollope. People who don’t have money don’t travel anymore, is the real punchline here. “On the Greek islands the simplicity of life gives your spirit a chance to come out...” we are told. “You feel more subtle and alive - and the more of life you get the more you want. You start to feel anything is possible.” Can’t have that.

The final pages of this all-to-brief retrospective focus on Dakin’s relationship to fantasy itself. A two-page feature called “The Hobbit” sees Dakin pulling a book out of a cardboard box and beginning with those familiar words, “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.” He ends up carrying the book around for the next few days: in bed, in a pub, on a train. That’s the story. With such wonderful brevity of expression, Dakin communicates the heady and gratifying sensation of traveling without moving. A free evening cruising down to Esgaroth. Doesn’t seem that far from writing those pleasing little books about Batman and Spock, does it? Easy work for an honest soul.

A few pages later, Abe encounters King Arthur, who steals his ice cream cone. But not before a brief exchange on the matter of responsibility: “Like you," Abe says, "I tried to put the sword back in the stone, and it nearly killed me.” Whimsy gets such a bad rap in this day and age! Is this a prelude to another release? Are we in for a more definitive collection? Again, the present volume offers no clues. It is merely what it is. A Trial Death resembles nothing so much as an urgent bulletin from a more deliberate era, an endearingly modest collection from an endearingly modest cartoonist. Give it a go. I think you’d quite like it.