Joe Quesada has escaped from his life sentence. Granted, 'chief creative officer of a multimedia superhero entertainment juggernaut' tends not to be the kind of captivity from which one struggles to escape. Yet after nearly a quarter century with the company now called Marvel Entertainment–a tenure that saw his ascent from co-editor of the scrappy Marvel Knights imprint to editor-in-chief of the comics line as a whole, to the nebulously high-ranking role of CCO, overseeing the company’s suite of multimedia properties–Quesada was beginning to seem as much a part of the Marvel furniture as Stan Lee had been 60 years earlier.

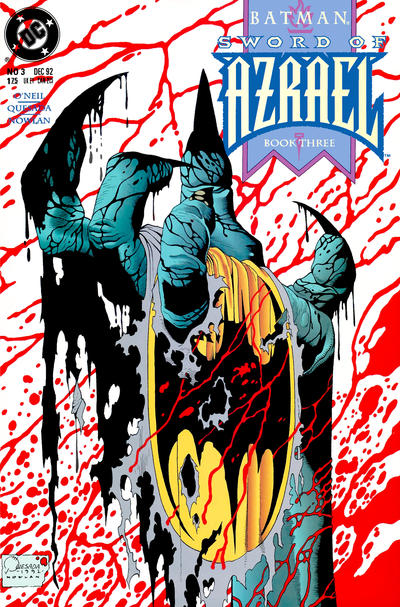

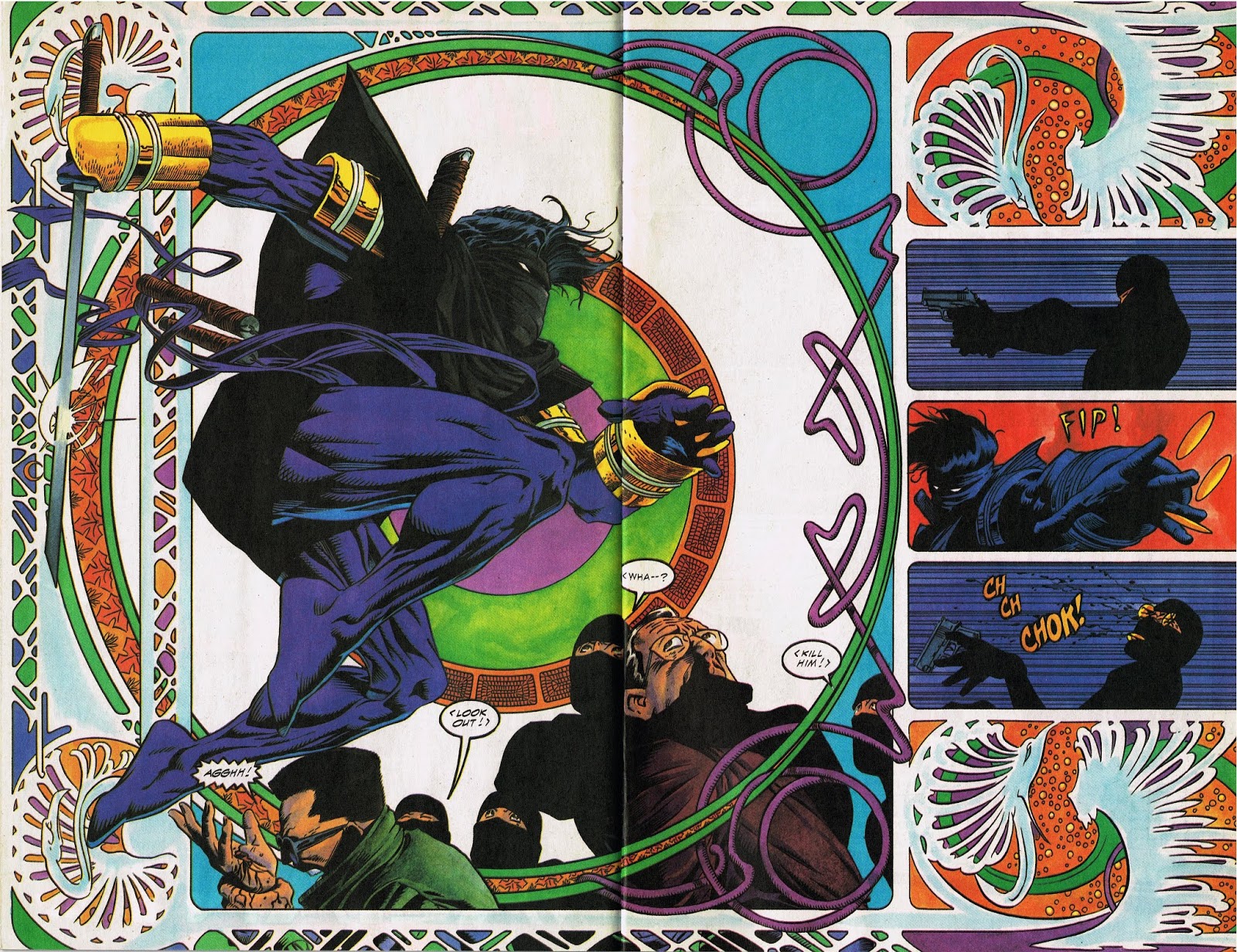

Easy to forget that before he was a Marvel institution, Quesada was a flashy hotshot artist in his own right: co-founder of Event Comics and co-creator of the firefighter superhero Ash with erstwhile creative partner Jimmy Palmiotti; designer of the haute '90s costume of Batman replacement Azrael; and work-for-hire penciller of comics like The Ray and Ninjak. Easy, too, to overlook the fact that it is Quesada as much as anyone who was responsible for the tone and ethos that we associate with 21st century Marvel - one that would in time metastasize into the ubiquitously quippy and explosive beats of modern superhero cinema. So there’s an argument to be made that Quesada wasn’t just a fixture at Marvel, but a fountainhead of contemporary pop culture, for better or worse. And in May of 2022, he packed up his office and walked away.

What followed was a period of radio silence from the otherwise outspoken Quesada, punctuated by occasional and unexpected announcements. First came the news at last year’s New York City Comic Con that he would be drawing a series of variant covers for DC Comics, his first work for that company in two decades. And then, more unexpectedly, Quesada unveiled his directorial debut with a short film entitled FLY; the short first screened at the Utah Film Festival, where Quesada won the award for Best Short Film Director and an Audience Choice Award. It moves next to the Zions Indie Film Fest in Utah, March 15-16, and the Garden State Film Festival in New Jersey, March 23-26.

For his first full interview since leaving Marvel Entertainment last year, Quesada sat down to talk about the challenges of taking on the medium of film, his biggest accomplishments and regrets from 24 years at Marvel, and what he thinks about the future of the comic book business.

-Zach Rabiroff

ZACH RABIROFF: You recently made your moviemaking debut with your short film FLY at the Utah Film Festival. How would you describe what the movie is about?

JOE QUESADA: FLY is about this young, small-town girl who loves to tell stories. She lives in a beautiful small town she calls the most beautiful place on earth, but she’s decided she wants to apply to one of the best universities in the country for anyone who wants to become a writer. And she basically is waiting for that acceptance letter to come in, and she gets a letter, and… stuff happens. So, you know, it’s a very simple story: I think it taps into my love of O. Henry with twists and turns, but that’s really it at its core. And it’s kind of meta in that sense that, you know, Maria [the main character] is telling you a story, and you then have to decide yourself: is she a reliable narrator?

So how long has this story been gestating for you? Is moviemaking something you’ve been wanting to do for a while?

I don’t know that there’s a lot of my own life in there. But I remember talking to Brian Bendis-- I think we were at Carnegie Deli and we had just broken for lunch at one of our writers retreats. And I’m like, you know, I have this short story, I’m thinking about doing it. And I pitched it to Brian, and Brian’s like, “Oh, you’ve got to do it, you’ve got to do it!” So I think I’ve had the story maybe for five to six years, and thinking to myself: I work for a living, so I’ve got to find time to do it. And then COVID hit, and even though I was still working remotely, I didn’t have to go to the office, and it just seemed like the perfect time to exercise those muscles.

I had been fortunate enough that Marvel had allowed me to direct a four-minute short for Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. And one of the things everybody knew at Marvel was how much I wanted to direct right when I got into comics. But then life took over, comics took over, and Marvel called, and away we went. So prior to the "Slingshot" episode, I ghosted some directors on Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., just to get a sense of the full episodic thing. And the goal was that eventually, in maybe season 2 or 3 of one of our shows, I get a shot to direct an episode. And true to form, Marvel said, “Hey, we want you to direct an episode of Runaways” - it was supposed to be at the end of the season, but as my schedule turned out, I was in the middle of doing another project for Marvel. So I told [publisher] Dan [Buckley], how about we do season 4 of Runways? Well, there was no season 4, so that opportunity was missed.

So I just figured, okay, let me create my own opportunity, and we did FLY, and we all had a blast doing it. And the thing with it is, it’s 180 degrees removed from what I’ve been doing my entire working career, right? It’s not a comic book movie. I wanted to step away and show that I could tell stories that don’t involve somebody getting punched, you know? Somebody shooting lasers from their eyes.

Were you drawing from any particular influences, either in terms of writers or directors, that you wanted to model your movie on?

It was less that and more tone. You know, there's a lot of different stories you tell: grim, gritty stuff or big, giant, epic stories. And I just wanted to tell something small. You know, my daughter’s grown up as a figure skater, quite often if I’m doing a panel or a talk, one of the things I like to talk to young creators about is how learning how to fall properly - i.e., learning how to fail properly. Well, I made that connection by watching my daughter. In order to land a jump at a competition, she has to fall hundreds and thousands of times. So you have to learn how to fall, and not just protect yourself.

That brings up an interesting point: the movie isn’t just drawn from the experiences of your daughter Carlie, but it also stars Carlie, too. Was the movie written from the beginning with her in mind as the lead?

No, because, first of all, she does not want to be an actress. I had to beg my daughter to be in my movie so that I could try to be a director. So she came in, and the the movie changed dramatically from the original [draft]. In the original scripted version, almost the entire story is told in voiceover, and that that's not ideal, right? But no one in the movie has any acting experience, and the idea was that we could have them go through the motions of the characters, maybe recite a few lines you could hear, but the story could be told when we record in the studio.

So on our first day of shooting, as we’re setting up for the shot, I could hear [Carlie] rehearsing in my earpiece, and I’m like, that doesn’t sound too bad. So I have my computer, I wrote down a few more lines, and I gave them the script. And they nailed these lines. So now I start thinking to myself, I’ve got to reinvent this whole thing. So every morning, I’m up at 4:00 AM writing dialogue. Because there was no dialogue, right? So that’s how the movie sort of took over.

Was it a challenge for you to be bossing around your family and friends as a director?

Well, anybody who knows me knows I’m not hamfisted, you know, even as editor-in-chief. That’s not what I do. But, yeah, with my daughter and I, it was a different thing when she’s taking direction from her father. So sometimes I would have to relay the direction through somebody else – you know, she was at that age while we were filming it that she was like [makes growling noises]. So I had to twist her arm to do the movie, but once the movie was done, she was very, very proud of it.

You’ve spent so many years as, primarily, a comic book artist. Were there things about this new kind of visual storytelling on film that you didn’t expect, or that caught you off-guard?

So, there are moments of voiceover in the movie, right? Not nearly what I used to have. But somebody whose opinion I trusted told me, “You need some beauty shots in here, because right now this place could be Bakersfield, California for all we know.” And then [after I added them], I didn't get any notes from people about, “Wow! Those shots are beautiful.” No comments at all. And I was like, that’s really weird, because there are some really nice shots in there.

And then it occurred to me that every one of the beauty shots had really long, descriptive voiceover that the audience knows is pertinent information for driving the plot. And I came to realize that this is what we as humans do, right? We can only take in so much information at one time. If I’m telling the audience 'listen to the voiceover because what she’s saying is important,' they’re not really seeing the shot. So I started pulling back [on the voiceover], and suddenly I sent the movie back out for the second round: “Oh my God! The beauty shots! They’re fantastic! Did you do reshoots?” No, I just took my stupid voice out of it and let the movie breathe.

And that was a real lesson, because it’s not something you think about. Because as readers, you read, look at the phone, look at the beautiful drawings, read. It’s symbiotic, and that’s not the way it works in movies, because in the movies you don’t have the opportunity to just listen and then watch. It’s all intertwined.

That’s really interesting, because I think it’s something a lot of people wouldn’t think about: that in a movie, you’re responsible for what the audience takes in and when, whereas in a book or a comic it’s the reader who has the luxury of setting the pace.

Exactly. Exactly. You know, when people ask me about horror comics, my thing is that it almost never works in comics. Because in horror movies or anything sort of visual, the director and the performers select the timing by which you get scared, and in a comic book you’re selecting the timing. So it’s next to impossible for you to scare yourself if you’re the one turning the page.

If you don’t mind my throwing some comic questions your way while we’re on that topic: you recently left Marvel after more than two decades. There are people who commented that they thought you were going to be a “lifer” for sure. So why now? What made you decide to do it?

You know, I’ve had these discussions with Dan Buckley, our president, for years. And it started off when I was editor-in-chief, and I had been doing it for a while, and I remember Dan and I had this conversation and I said, no one should do this job forever, right? I’m already at the point where I’ve been doing it as long as Stan Lee, and I’d like to do something else. And then this chief creative officer thing came around, and I was doing both jobs–creative officer and editor-in-chief–while we were preparing for the changeover to Axel [Alonso, Quesada’s successor as EiC in 2011].

Well, probably the summer before COVID, there was a change in structure at Marvel, where Marvel TV went over to the Marvel Studios side-- which, you know, I completely understood the math behind that, and the reasons behind that. But I’d also been at a point where I had really kind of done anything and everything that there is to do at Marvel. And the thing that I was that I was aching to do was to do the stories that I've been writing in a journal for a very long time which are not superhero stories - nothing that would be of any interest to Marvel. And it just came up in a number of talks with Dan, like, I think it's time, right?

But it also came out of something my father said a very long time ago. He was a big sports fanatic, and he always said, “Listen: whatever it is that you do for a living, if you have the opportunity to leave at the top of your game, before your skills wane, leave and try to do something else.” Like, people have fond memories of Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio because the minute they sensed their skills were waning, they called it a day.

The Beatles break up after Abbey Road…

On a high note, right? And the truth is, everybody that wanted the Beatles back together again, you know, being the world’s biggest Beatles fan myself, I’m like, no, no, no! No matter what they do, they could write the next Sgt. Pepper's, it won’t matter. It’ll always be compared to what you do before. So I’m not saying my skills are waning. I’m just saying there’s nothing I could do at Marvel that I think people are going to go, “Wow, okay, he’s doing X-Men.”

You know, I come from the world of creator-owned comics. If you look up really early interviews with me, I get asked the question a lot: “What is it that you miss the most now that you’re editor-in-chief?” And I'd say, you know, I miss the actual act of creating from scratch. I miss drawing. It’s kind of like a phantom limb, you know?

And of course you’re already starting to do that with the Batman covers you’ve been doing for DC. Did you find that your style as an artist has changed since the last time you were really active?

No, because I have been actively working on a project… well, still am actively working on a project that's been a slow burn. So I’ve been drawing. I draw every day, I write every day. I’m at my computer by 7:30 AM, and I will work until probably midnight. And there was a time during my tenure as editor-in-chief where I was just so busy, so slammed, that I hadn’t touched a pencil in a while - you know, several months. And when you don’t, it’s a chore to get it back, right? So you go through doubts, like oh my god, have I forgotten how to draw? I’ve lost it! That’s the worst, because then the self-doubt comes in.

But it’s muscle memory, you know? And thankfully, I’ve been working on this project for a while, and Marvel covers here and there, but that’s not the same skill as actual sequential stuff. So that's something I've been working on for a while, and I'm going to be doing more and more of that. And that's really exciting to me, because after the Marvel project, it'll be stuff that is my own. At some point, I’ve got three or four ideas.

When you look back, is there anything in particular that you feel like you're most proud of from your Marvel tenure?

So, the thing that got me into comics was just happenstance. I was part of that, just, creative boom at Marvel. To be involved in an American success story, that I was involved in that team-- those people did something that very rarely happens. You come into a company that used to be incredibly popular and viable, and is no longer, and you turn it around and make it not just profitable but it became a model, right? Steve Jobs and the people at Apple did that, but just looking at the history of companies in the entertainment world, Chapter 11, going through bankruptcy. [A revival on that scale] doesn’t really happen often, so to be a part of that, just a little footnote in that success story, that’s kind of cool.

Do you feel like that liberated you in a way you might not have been in later periods, the fact that because Marvel was in the midst of bankruptcy you could kind of do anything?

It did and it didn’t. It wasn’t so much that you could do anything, because you can also view it as, you know - I got the best seat on the Titanic, right? I can go down as the person who destroyed Marvel. So there are those pressures. But it did allow us to pose the argument-- because it’s not just comics, it’s any industry. If you’ve been in the industry long enough, you will find people that will say, “well, things have to be done this way, because that’s the way things are done,” and they will say that even as the ship is sinking. “No, you’ve got to do it this way.” So what it did was allow us to say the hardliners within Marvel, within the retail community, within the commerce community, that it doesn’t have to be done that way.

And we’re not the only ones who have created that kind of an idea. I mean, the Image partners, they did that back in the day. But you’re fighting against the tide-- and in this case the tide that we were fighting against was just that the entire boat was sinking. It was on the verge of going out of business, so get scrappy. You just try different things, and in the midst of the Marvel success there were gazillions of failures. And we can point to things and say, well, that worked well, that didn’t work, but you’ve got to make the attempt, because the stagnation was killing us. It was killing the entire industry. So it was a good time to come in and pitch some crazy shit, because why not just try it?

Is there any project in particular that stands out to you as being that kind of good, crazy shit, so to speak?

Oh my god, there were so many that we were doing. But the Ultimate [line] would never have happened if the climate hadn’t been that way. It was reviled before anyone read a single issue. You know, “We don’t want to read this, John Byrne just did Spider-Man: [Chapter] One, what was wrong with that?” Nothing, it just didn’t change anything!

So we were looking to change something - looking to change the narrative, and try to tell stories in a different way. I mean, people forget - those first six issues of Ultimate Spider-Man, Peter never puts on the costume, ever. And you can’t take it away from the creative team: Brian [Michael Bendis] wrote the hell out of that thing and [Mark] Bagley drew the hell out of it. It was just perfect for the time.

And I think that was also the time when we were printing to order, which was freaking retailers out. “What do you mean, we can’t get backorders?” Well, we can’t afford to just keep a stock of stuff, we’re in Chapter 11. So that actually helped the book, because it became impossible to get. So we went to a second printing, and then the first printing skyrocketed in price because it was an actual collectible - it just blew off shelves because retailers didn’t really think it was going to do anything.

So given how liberating that time was, can you look back and feel like there are any missed opportunities - things you realize now you could have done but didn’t? Are there any things you did do but wish you hadn’t?

Not really, no. I’m sure if I think back to my archives I’ll go, oh yeah, there was that thing, but there were a lot of happy accidents as well. You know, like, my first week as editor-in-chief, I did not move into Bob Harras’ office, because I just felt that it had come as such a shock to the staff. And then the second week, I moved into Bob’s office, and I opened one of his drawers that I just assumed was empty. And there were just a bunch of proposals, and I just start paging through them. And within these proposals was a proposal by a young Brian Vaughan called Runaways. So I’m like, wow, this is good, right?

There was a lot of stuff that happened like that, so I’m sure there were things that I shouldn’t have done. There were some things that were said during that era… let’s clear it up here, because I always hear this quoted. There was this interview, an exposé on me in the New York Observer, in which I had a very off-color quote about Superman, and it became incredibly controversial. As it should have.

INTERJECTION: In the interest of both clarity and historical accuracy, some elaboration is in order here. Quesada is referring to a profile which appeared in the Observer on April 29, 2002, which depicted the “trash-talking” (their words) editor-in-chief as a rabble-rousing bad boy set to shake up his industry. The passage in question, which did set off a minor scandal on the eve of the Spider-Man movie premiere, reads as follows:

Mr. Quesada is convinced that some good old-fashioned gloves-off rivalry will be good for business. “I liked it when the two companies hated each other,” he said. “It made it better for the fans. You know, if you like DC, then you hated Marvel. If you like Marvel, then you hated DC.”

“What the fuck is DC anyway?” Mr. Quesada said, stoking the fires. “They’d be better off calling it AOL Comics. At least people know what AOL is. I mean, they have Batman and Superman, and they don’t know what to do with them. That’s like being a porn star with the biggest dick and you can’t get it up. What the fuck?” (Paul Levitz, DC’s president and publisher, declined to comment for this story through a spokesperson.)

To return to Quesada’s explanation:

The origins of that are that they asked if a reporter could embed with me for an entire day, just to see the first artist [who is also] editor-in-chief. So I said sure, and the reporter sat in my office all day long. And it happened to be a day where a fan had won–I think it was through the Hero Initiative or some other charity–a lunch with me, which I love doing. So when the fan got there, I looked at the reporter and I’m like, you want to come along? He’s like, “Sure, okay, but this is all off the record until we’re back to the office.” No problem.

So we go to lunch, and, you know, the fan is a hardcore Marvel fan. Everybody in that lunch is hardcore Marvel. So we’re just ragging, you know, going off on DC this, DC that, [Quesada imitates machine guns firing] we’re gonna kill ‘em in sales! And somewhere in there, I said that, right? Just said it in conversation. Not thinking anything of it, and completely forgetting about it.

Then the article comes out, and he uses that quote, and it infuriated me. Infuriated me. Because I’ve always played by the rules, and this person did not. I mean, he had a juicy quote and he used it, and I should just never have invited him to lunch, period. Because here’s the thing: DC talks about us the same way. It’s just trash talk, that’s all it is. It’s not meant for the public, it’s for a laugh amongst friends and associates at lunch, and that’s what happened.

So when it came out, I was really mortified, and I thought, I could be fired for this tomorrow. And instead I got full support from the company, because they understood exactly what happened. As a matter of fact, there was some laughter at the very highest levels of the company - I won’t say who it is, but one of the higher-ups of the company comes into my office with the [Observer], and I’m like, shit, am I fired? And they point to the paper and they go, “Did you say that?” And I’m like, yeah, I did. “That’s fantastic!” And they walked out, laughing hysterically. So it was a crazy time, and that is the actual story of what happened. It was not meant to be-- I was poking and prodding and stuff, and Bill [Jemas, then-Marvel President] was going way overboard on poking DC.

Right, right, the Paul Levitz jokes in Marville…

Because Bill was getting personal, right? He was going after Paul and stuff, and I’m just standing back going, oh god. And I would have my share of fun with DC and poking them and stuff, just trying to get a little rise out of them. It was really more for fandom than anything. But I never would have said that in an interview in public, because that’s just not the kind of thing that I ever say in public. But it was said, it’s out there. I laugh at it now, but I know it was a rallying cry at DC for a long time.

Here's the thing: [whispers conspiratorially] it didn’t help them. We still kicked their ass. [Laughs] I’m still trash-talking, man, and I’m not even at Marvel anymore.

Yeah, I mean, it really did become a whole part of the fan culture at the time. Because obviously Bill was doing it, but it really felt for the first time in a long time like that storied Marvel/DC rivalry was coming back. And I think people were never sure how genuine it was, or how much was just to get the fans into it.

Yeah, I mean, Bill took it to a level I would not go. But I’m not going to tell my boss to shut up, you know? I mean, you know Bill, he does what he does. But Bill took it to a level where it was personal, and Bill also took it to a level with retailers that I wasn’t comfortable with. I know he was trying to get a rise out of people, but, you know - Bill gave me my job. So I’m always grateful for that trust. But we had different styles.

But that’s why to this day, that was one of my two moments-- it did make me wary of, whenever I talk to the press, sometimes off the record will not always be off the record.

You said one of two moments?

Oh, yeah, I always talk about this one openly, but when I was working at Valiant, long before there was an internet, they had promised something in a contract, and there were certain incentives and bonuses and things where if we hit certain levels of success, money would kick in. It wouldn’t be Image money, but it’d be money. And then through a few sales shenanigans, those goals became impossible to hit.

So I was infuriated, and I did the analog version of what I see people do today-- and I cringe, because I sort of… I wrote a hot letter to [Comics Buyer's Guide]. A hot letter, talking about Valiant screwed me this, and that, and the other thing. And then literally the minute I put the stamp on it and put it in the mailbox, I went, I don’t know about this. And then when it went to press, I felt even worse, right? Because I was still angry at the folks in that moment. I made peace with a lot of them later in life, but it was a huge mistake, because at the end of the day, Valiant is not going to respond to the letter. They’re not going to get back to me. I’ve burned a bridge, being new to the world of entertainment and media and business stuff, not realizing that the people at Valiant can end up somewhere else. And now I’ve created an enemy that will always be problematic.

Probably not unlike when I see creators vent about stuff like this, and not just burn their bridges, but set them on fire and throw dynamite on them, right? And then realizing that they did all this for what inevitably, really, is about five or six people on the internet. So they’re like, “You did great!” But meanwhile, they’re not paying your rent. They’re not signing the checks. So just on a personal level, I let myself down. I never wanted to do that again, and never did.

So when you look at the comic business now, what's your read on the state of the industry? Where does it stand, and where is it going?

Comics are always going to be around. They’re going to go through ebbs and flows. Some years might be tragic. But it’s a beautiful, wonderful art form, and it is going to survive. One of my biggest pet peeves with the industry as a whole is that there is no other entertainment industry that is so happy to predict its own demise. People that love the medium can’t stop talking about, “Oh my God, we’re dying! It’s gonna die!” Or: “I can’t wait for it to die.” I don’t get that. I don’t get it.

It makes sense to me from people who have been rejected by the industry, who’ve been let down by the industry, and, you know, “If I can’t be in the industry, then there should be no industry,” right? There’s a lot of that, and if you read through subtext, they may not even know they’re saying it. But I’ve seen that happen. I remember Jimmy Palmiotti and I, when we were breaking in, sometimes we’d see an older creator sort of publicly venting about the fact that these Image guys are making so much money. And realizing that it’s a generational thing: these creators didn’t get the acclaim and the money that current creators get.

And Jimmy and I swore to each other that if we lasted long enough in this industry, we will find ourselves in positions where new creators have stuff we didn’t get the opportunity to do. But we should never, ever, ever be bitter about it. We should just go, times change, and be supportive. I just never wanted to be that, you know?

So, in terms of the industry itself, you know, it's filled with creative people. And it changes because it’s supposed to change, right? If you’re reading comics for a long time, guess what: this isn’t your Captain America. It’s another generation’s Captain America. But when you had your chance, and you had your Captain America, there was somebody much older than you thinking to themselves, “That’s not my Captain America.” It’s always been that way.

What about in terms of sales? Do you feel like it’s possible for comics to stay afloat through the direct market?

It’s hard to compare, because there’s no apples-to-apples comparison. Are we selling as much as we were during the booming boom [of the '90s]? No, but again, those weren’t actual sales, right? We had one person going and buying 50 issues of something, so you can’t compare that. Are we selling as much as we were during World War II? No, and that’s probably a more apt comparison. But in World War II, we were shipping off comics to servicemen. Comics were part of a patriotic movement to keep America together, so it was almost essential reading and escapism at the same time.

But considering that we were almost shut down, many, many years ago by the government - the fact that we’re here now: we’ve actually achieved the goal. Comics have been living in a self-imposed ghetto for a long time. We’re not going to do that anymore. Superheroes are all over pop culture.

Aside from superheroes, though, are there other genres or types of stories that you feel like we’re not seeing in comics right now?

No, not if you pull back your gaze, stand 10,000 feet above it, and look at what’s being produced in the world of book publishing, right? Just look at all of the different genres that are being produced as graphic novels - straight to graphic novels. Just looking at the work Ed Brubaker is doing, he’s releasing these hardboiled crime novellas [Reckless, with artist Sean Phillips, via Image], but it’s really a book market initiative. Comics? The whole thing? They’re everywhere. They’re part of the culture very much in the way we used to jealously view Japan, and we would see these people openly reading manga on the subway. Well, that happens now: people read comics on the subway. Back when I started, they were reading a comic, but it would be inside another book, right? That stigma is gone: we are part of the mainstream. We do everything. It could be in a different format, you know?

So then, do you think that’s maybe the future the business is heading in - something other than the monthly, direct market periodical model we’ve had for so long?

It’s hard to say. I mean, the direct market is a gift to comics. When you think about any other industry, when you say to them, we have a distribution model in which our retail partners order you on a non-returnable basis, they look at you like you’re lying.

So do I see that going away? I could see that going away if it’s mismanaged, right? The whole non-returnable comics thing, we debated this at Marvel for a long time. It’s the equivalent, I think, of Hollywood and everyone’s rush to get into the streaming business because they thought that was the future, and literally destroying the golden goose which was movies and movie theaters. They willingly jumped into the streaming world, only to realize it’s not a profitable business. It’s an additive business, but your core business was movie theaters and linear television. And you’ve abandoned that willfully.

It's the same thing with the direct market, and that willingness to turn it into the newsstand and destroy a business model that has been very healthy and working for everyone. Because it does affect the cash flow for retailers, right? If they’re given something where they can order as much as possible - great, I’m going to order as much as possible, and then return later what I don’t need. But for that month, their cash flow is tied up with that one product. And this was happening for a while, and instead of diversifying their dollars and maybe try out this independent or this title, the bulk of their dollars that they were allotting for that month’s purchases now goes into returns.

I mean, here’s the thing: it’s a really great feel-good announcement, our books are going returnable. And you’re going to get a lot of people online and in the press saying, “Man, it’s awesome they’re doing that.” It is a terrible business practice. It just is.

You know, nobody gets into comics–retailers, artists, writers–we don’t get into it to get rich. We get into it because we love it. Some of us are fortunate enough that we make a living at it. There’s a lot of places for writers and artists to make more money than comics. So they’re doing it for a reason, and the only thing I can think of is simply love.