When Nate McDonough first started flipping comic books as a full-time job, he estimates he spent some 60-80 hours a week searching shops and then listing and shipping his finds through eBay.

When Nate McDonough first started flipping comic books as a full-time job, he estimates he spent some 60-80 hours a week searching shops and then listing and shipping his finds through eBay.

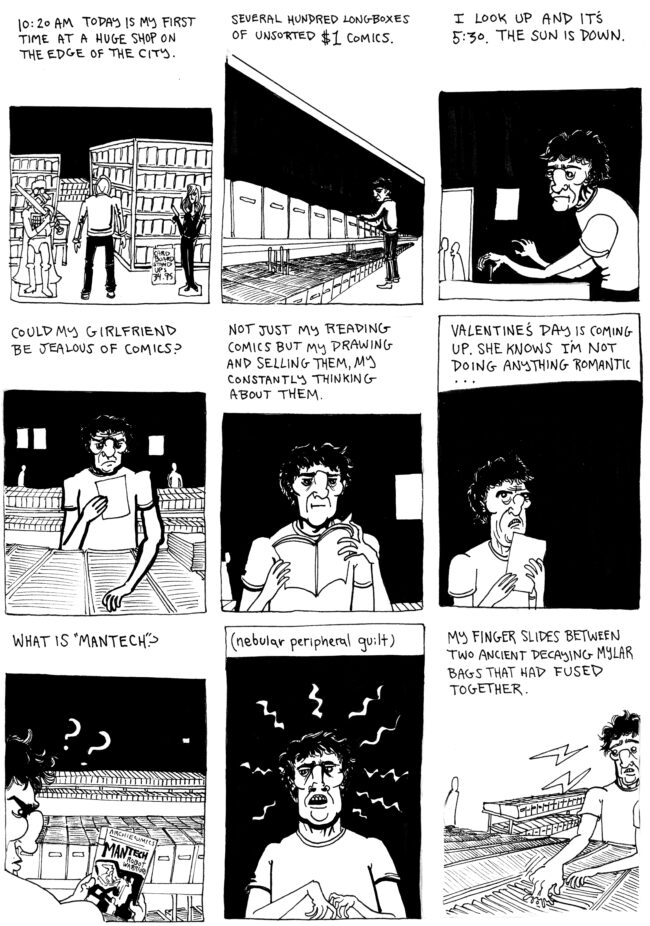

“A lot of that was a delight, though, because a lot of those hours were biking to and from comic shops and going to new comic shops and digging around in comic shops,” he told The Comics Journal in his home in July.

Now he’s gotten it down to about a 40-hour-a-week investment, and he does it on top of 20 to 30 hours a week of making and selling his own independent comics.

While these two endeavors exist in different comics spaces -- traditional shops with comics from the largest mainstream publishers and the alternative, independent scene -- McDonough threads them with his most popular comic strip, Long Boxes, an autobiographical comic chronicling his comics flipping.

McDonough, a 33-year-old Pittsburgh resident, has been making his comics for more than a decade. At 21 years old, he started Grixly, a series that collects minicomics he creates, often containing profane gags and autobio foibles. It gained a spike in readership about five years ago. A few years after that, he started flipping comics full-time and debuted Long Boxes within Grixly, which produced another spike in readership.

Garnering a readership for Grixly proved brutally difficult at first. When his visibility spiked some five years ago, it spiked “from nothing,” according to McDonough. He remembers giving 10 copies of its $0.99 first issue to Bill Boichel, the owner of Copacetic Comics Company, and then coming back a week later with 10 more copies of the first issue and 10 of the next, only to hear that none of the first batch sold.

“I think I sold three things in five years, because it was just bad comics, you know?” McDonough said. “Who’s going to go way out of their way to order these extremely low resolution, low quality, low print production [comics]? Just everything was mediocre to terrible about them.”

Boichel recalls those early attempts to sell Grixly, and commends McDonough for sticking to it. Nowadays, McDonough’s comics, especially the Grixly issues with Long Boxes, consistently sell at the shop.

“Relative to anyone else working in Pittsburgh who’s not a full-time professional, he’s probably the most prolific cartoonist in Pittsburgh,” Boichel said.

McDonough didn’t expect Long Boxes to be a hit and didn’t even originally plan to continue it past its first installment.

“How much more could there possibly be to say about it than that? And then I did a second seven or eight pages, and, again, I was like, ‘surely I must be scraping the bottom of the barrel now,’” he said. “I feel like I try to keep that in focus. I remain highly motivated, and I feel like I’m not running short on material.”

He realized recently that using the framing of Long Boxes has given his autobiographical work the kind of reader engagement and attention for which he’s been looking.

“It’s probably been a good thing for me in a way that I get this dose of modesty from, yes, okay, there are people who are willing to participate in this delusion that you do have these marvelous ideas to share with the world,” McDonough said, “but you just have to phrase your answer in the form of, ‘it happened at the comic shop.’”

As a child, McDonough obsessively followed Wizard magazine’s price guides, to the point where he could tell you at any time, by the dollar, the value of his comics collection. That obsession hasn’t left him.

McDonough works on his comics flipping seven days a week, whether it be visiting stores, listing items on eBay or making roughly weekly trips to the post office, where he has come to know every worker by name. At McDonough’s home, he showed me several long boxes filled with comics listed on eBay.

Primarily using completed eBay auctions as research, McDonough sifts through local shops’ comics inventory for issues worth more than they’re marked. He also frequently completes sets to sell; he constantly sells sets of the Daredevil storyline "Born Again" from Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli, for example.

About 95% of the time, he ends up profiting, he said. Another 4% of the time he breaks even, and about 1% of the time he loses money.

McDonough features the specific comic shops he visits in Long Boxes and portrays them in ways that will be familiar to Pittsburgh area comics fans. He draws Eric Bachman, owner of Bill and Walt’s Hobby Shop in Downtown Pittsburgh, in such a way that I can practically hear his big belly laughs just looking at the page.

He buys most of the comics he flips through New Dimension Comics, a chain in Western Pennsylvania and Ohio.

“If it’s a New Dimension I’ve never been to before, I’ll buy two long boxes of comics and pay $3,000 and then spend a month turning that into $7,000,” McDonough said.

One of those Pittsburgh-area stores, New Dimension Comics - Waterfront, made McDonough realize he could make a living out of flipping comics. Sales like 50% off $1 comics especially come in handy. As shown in Long Boxes, there have been several days McDonough has turned up at the massive store when it opens at 10 a.m. and stayed until it closes at 9 p.m., neglecting to eat, check his phone or take any other kind of break.

Tim Cope, Assistant Manager for New Dimension Comics - Waterfront, met McDonough a few years ago, when the Waterfront location first opened.

“He stuck out in my mind because he is the only customer we have that comes in and gets comics but rides his bike,” Cope said. “When you think of someone riding their bike and getting comics, you’re thinking, ‘oh, this guy gets like three or four comics.’ That’s not the case with Nate. When Nate comes down, he’s getting a pretty big haul.”

Cope said he’s learned a lot about selling comics from McDonough. And one day, McDonough brought in a sample of his own comics, which Cope found to be impressive and professional.

“You can tell his passion for comics doesn’t stop at selling books. It’s front to back. Reading them, collecting them, selling them and making them. And I think that’s one of the things that’s really fun about him,” Cope said. “I never know which part of the conversation I’m going to get when he comes in.”

Blue Lives may be McDonough’s most prominent work outside of Long Boxes. The Comics Journal reviewed it in 2019, calling it “delightfully crude and messily insightful.” The comic follows two cops stumbling around and acting like jackasses. McDonough channeled his raw frustration with cops into the book, which resonates now even more than it did when it originally released a few years ago.

“I’ve found that whenever I do make a book, the faster that it comes to me, the more I seem to enjoy it or the more worthwhile I think it is when it’s actually done,” McDonough said.

McDonough draws with a coarse style to create often gross imagery, evident in Blue Lives and everything else he does. A recent issue of Grixly sports a cover with a minion, one of those yellow-skinned, blue overalls-wearing children’s cartoon characters, slitting the throat of another minion, its blood gushing onto the street. Long Boxes ends up emerging as the least gross-looking of his work, but it doesn’t shy away from that when portraying, say, particularly strange people McDonough runs into while flipping comics.

Boichel appreciates the unpretentiousness and uniqueness of McDonough’s comics art.

“His particular sensibility is original,” Boichel said. “It’s an amalgam of all the stuff he’s interested in, which is especially horror, he really has a thing for horror, but then it’s like horror, superheroes, and then also the snarky, '80s, Fantagraphics, independent [style], and it’s just all kind of rolled into one.”

Daniel McCloskey, a fellow cartoonist and friend of McDonough’s, discovered McDonough’s work at Copacetic Comics Company.

“[McDonough’s art is] still doing the same thing to kids in Pittsburgh, from what I understand, that it did to me when I was 20 and found it,” McCloskey said. “He’s still drawing at the same pace and in the same kind of grotesque, weird style.”

McCloskey knows someone who teaches a small art class in Pittsburgh who would ask their students to bring in a piece of artwork they found inspiring.

“Most kids would bring in art magazines or historical pieces of fine art, like pop culture stuff,” McCloskey said, “but there was always at least one kid that would find one of Nate’s comics just lying in a coffee shop and go ‘Look at this! Isn’t this so weird? I think this guy lives around here!’”

The hard work McDonough puts into making comics impresses McCloskey.

“He is constantly working and producing things that are, I think, for himself first and that he shares with the world,” McCloskey said. “If you see him out in the world, 99% of the time he’s going to be drawing.”

I can attest to this. When I visited McDonough for this article, I found him outside his home on a chair in the grass, barefoot, wearing gym shorts and a t-shirt while he drew in a notepad. McDonough said he has a constant stream of ideas and an ability to draw, so the challenge is squaring that with his limited time.

“I only have like 15 to 20 hours in a week where I can make it happen,” McDonough said. “I’ve found a style of economy.”

Though he’s been in comics for so long, McDonough may still be early in his overall career. He just recently began distributing the free first issue of Imperial Egg, an anthology for which he’s publishing, editing and contributing, made with newsprint.

One particular, recent gag in Long Boxes seems prescient. McDonough drew a goofy white silhouette looking through a box of comics alongside something a buddy of his once said:

“One day a comic hunter will be searching for your comic hunter comic… and the universe will collapse under its one remaining pillar and we’ll all be free, so thanks!”