After 32 years, Kentaro Miura’s Berserk has finally concluded. After three-some odd decades -- three decades spent following the Black Swordsman Guts and his entourage as they carved their way through ever-grizzlier carnal spectacle, three decades stuffed with speculation over how, exactly, the infamously bleak chronicles of Guts’ quest for revenge against one-time comrade Griffith could possibly conclude with the happy ending its author once alluded to, three decades of increasingly baroque plot developments that left readers crafting ever-more baroque theories to explain away Berserk’s manifold mysteries (what, exactly, is the connection between the mysterious Moonlight Boy who shadows Guts’ entourage and the resurrected Griffith? Is the Skull Knight, as all signs suggest, the wandering spirit of the mythological king Gaiseric? If so, what, exactly, is the connection between him and the Godhand? And what, exactly, are the Godhand? What final purpose are they striving towards behind all their cryptic intonations about “causality?” Did Miura plan to reintegrate the never-reprinted 83rd chapter and its revelations back into the Berserk cosmology, or was his never-budging decision to drop it from all subsequent collected releases proof that it should no longer be considered canonical?), three decades spent trying to calculate what Guts’ final kill count would stand at (SkullKnight.net has long maintained an exhaustive, customizable search engine citing every last causality Guts has been responsible for, numbering a confirmed 1,190 as of vol. 37), three decades lousy with jokes about Miura’s ever-more-frequent hiatuses, about how Miura’s love of the videogame series Idolmaster was the origin of his truancy, about getting Guts and his entourage “off of the fucking boat” -- devotees need wonder no longer how the story ends. We know how it ends: in the early hours of a late May Thursday, with an announcement from the author’s publisher that Miura passed away some weeks prior of aortic dissection at the age of 54.

It seems unreal. Impossible, in fact. Berserk is a work of such cultural penetration, its influences so widespread and so long-lived, that it feels less like the work of any one man than an archetype dredged up from our collective unconscious: the series’ legendarily grotesque violence is so iconic that you have only to mention its name before defenders and detractors alike will offer up endless discourse about “horse rape” and “the Eclipse,” titles and images once absent from the lexicon that now possess such primal associations of revulsion and disgust that they seem to have always been there. One can point without effort to how baldly Hidetaka Miyazaki’s genre-defining series of Souls games have borrowed from the comic for iconography and monsters and armor and weapons, yes, though it might be more broadly interesting to note the direct correlation between Berserk’s runaway success and the explosive popularity of the genre as a whole given how ubiquitous the sight of scrappy protagonists swinging around comically oversized swords modeled directly after Guts’ iconic Dragon Slayer in dark-fantasy proxies of Middle Europe has become in the decades since the comics’ first publication (Miura himself noted something of this when he observed how before Berserk, “Fantasy... wasn’t a well-known genre at all” ). Among the artists who have cited Berserk as an instrumental influence can be counted superstars such as Hajime Isayama (Attack on Titan), Makoto Yukimura (Vinland Saga), Ryōgo Narita (Baccano!, Durarara!!), and Atsushi Ōkubo (Soul Eater), who went so far as to declare it his friend group's Bible; over its lifespan the series moved a staggering fifty million copies globally, while domestically Dark Horse Comics’ Director of International Publishing and Licensing has confirmed that Berserk was and remains the best-selling comic in the publisher’s storied history (edging out cultural cornerstones such as Hellboy and Lone Wolf and Cub); if nothing else at all one has to imagine there are more than a few tattoo shops that owe their continued existence to the always-popular and ever-ubiquitous design of the Brand of Sacrifice. Such was the series’ mythological aura that it was not uncommon for readers to joke about how it would be us on our deathbeds begging our grandchildren to explain the latest developments in Miura’s infamously long-lived epic while the author continued plugging away at his work, somehow and forever beyond the touch of time. Even the eulogies penned by his peers and collaborators seem struck by the impossibility of it all, with composer Susumu Hirasawa remarking “Once again, I hope we can get along earnestly,” as if he were merely announcing a new collaboration with his erstwhile friend rather than bidding him adieu, and artist Chica Umino writing more bluntly that “nothing has felt real for the past two weeks.”

Attribute that sense of the uncanny, perhaps, to how long-lived the series was: if there are other, younger manga that have long since surpassed Berserk in chapter and volume counts, there are only a handful of stories that can lay claim to a similar longevity: your Golgo 13, your JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure, your Cooking Papa and KochiKame. And yet it’s hard to think even these legendary series, had they met undue ends, being mourned with the collective cry of disbelief that resounded the world over with the announcement that Kentaro Miura had ended, and so with him Berserk. Surely there will be much wailing and gnashing of teeth and an endless number of memorials inked when Takao Saitō dies and the adventures of globe-trotting hitman Duke Togo come to the ignominious end their steely protagonist was always destined for; it takes no imagination to visualize the incalculable number of posing contests and tribute photos that will be emerge in the days after the seemingly eternal youth of Hirohiko Araki gives way and puts a stop to the lineal struggles of the family Joestar. What is harder to conceptualize is these authors’ deaths being met with so palpable a sense of incredulity: surely there was nowhere near so great a sense of public befuddlement when Crayon Shin-chan creator Yoshito Usui died, tragically premature though his 2009 passing was.

Maybe what makes it easier to process these author’s departures, and so accept them as inevitable even if unfortunate, is that their lives are coupled to works that either derive their appeal precisely from their fragmented, episodic nature (it hardly matters where you start with Crayon Shin-chan, say) or to works that are structured as a series of self-contained (if often interlocking) narrative arcs: had JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure left the latest arc JoJolion unresolved on the cusp of completion, there would at least remain seven parts before which saw their way to satisfactory endings. Consequently, perhaps what renders Berserk’s unceremonious conclusion so cruel and so ludicrous -- so inconceivable -- is the coupling of its venerable age with its structure. As an epic low fantasy that traces protagonist Guts’ development from birth through adolescence into adulthood, and the ever-developing dimensions of his grudge with former comrade Griffith, it was always intended that it should have a proper ending to a properly resolved arc that had been carefully developed to convey the whole of a world and life. That it traced this action in an unbroken line across 24 years of diegetic time and 32 years of our own -- ensuring that readers grew up alongside it, or were even born during its run -- only reinforced the sense that it was happening coterminous with its readers’ own lives; that it was not the fabrication of a teller so much as an honest chronicle of another world, parallel to our own but not in it, not of it, and so not necessarily defined or subordinate to it.

This has always been the great promise of popular speculative epics, fantasy in particular, that the author should by dint of scope and scale and vision render a new world -- one free from the mundane shackles of our own and so answering only to the limits of imagination -- in its entirety and in doing so capture something proximate to the breadth and depth we feel living through our own endlessly complex history. A world is not simply a collection of names and dates but a distinct phenomenological experience, a distinct way of being as well as seeing, and so it should be little surprise that the few other contemporary works to attempt so grand scale a project over so grand a period of time are also gargantuan sagas devoted to manufacturing planets in their wholeness. Could anything but another cosmos, captured down to the very last atom, cataloged down to the most remote annals of history, even begin to approximate the feeling of living in our own? What intimate work of fiction, no matter how well observed and psychologically astute, could begin to say something about the dizzying reality of living in a vast and interconnected history like our own? What perfectly frozen tableau of frustrated modern life, no matter how unsparing, could hope to provide the escape from our own wanting world that epic fantasy makes argument for by the brute force accumulation of facts? That these projects often take literal decades to unfurl is not to their detriment but to their recommendation, for to follow them -- to follow Kaoru Kurimoto's Guin Saga, which inspired Berserk, or A Song of Ice and Fire or The Wheel of Time or Gene Wolfe’s Solar Cycle or Jack Vance’s Dying Earth saga -- is to feel the scope of the world through time; by sheer happenstance the stories begin to take on other dimensions, only further enforcing our suspicion that there is something total about them, some essential element by which they might contain everything, especially those of us eager for escape from our own maddening universe. Unfortunately, such opportunities for unbridled creation often invite the worst excesses and the dullest indulgences, author after author populating book after book with databases and encyclopedias packed with proper nouns and abstruse terminology all meant to tie a vast, unwieldy assemblage of names and peoples together into a coherent world. As if the world was nothing but the agglutination of details. As if the whole not just of a single life but of an entire planet and its history and everything contained therein was nothing but a laundry list of facts and figures that could be collated on a spreadsheet or stretched across a globe, an atlas mistaken for the planet itself - the promise of the endeavor leads authors and readers alike, again and again, to mistake this potential for an inevitable quality. Somehow the description of a world is confused for the lived experience of being in it, as authors and readers forget that the first and perhaps most dominant quality in any experience is the sense of discomfiture that exists in realizing there will forever be a gap between oneself and everything else that is.

* * *

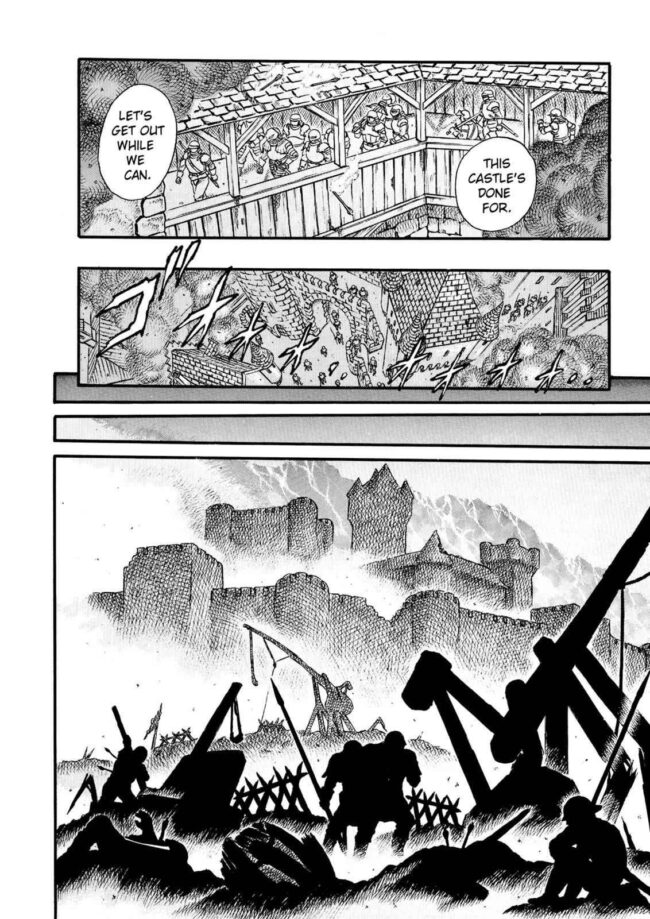

This, then, is the first and perhaps the most unassuming element of Berserk’s genius. Unlike so many of its peers, Miura’s masterpiece sparingly allows a glimpse beyond the ground-level perspective of nobodies trying to understand a world cut up by the machinations of higher powers only dimly apprehended. When first we meet Guts we are provided no context that could make sense of where exactly he is, or why exactly he’s so dedicated to carving a bloody swathe through the various abominations known as Apostles he runs afoul of; he seems to inhabit something like Hell, an unconnected, unidentifiable mishmash of haunted marshes and horrific castle towns connected through no politics, no history, no culture or religion but the certainty of extreme violence. It’s appropriate, given that Guts himself has no clue as to why his enemies exists or what purpose they serve in relation to the traitorous Griffith (nor, as it turns out, did Miura when he began to pen the series; per his interview with manga historian Yukari Fujimoto, he'd “hardly thought any of it out at first.”). Even when we are taken back in time to settings more mundane to observe the rise of Guts from foundling to raging avenger and afforded foreknowledge by our glimpse into his future, the lay of Berserk’s lands remains largely inscrutable, a dizzying procession of battles between mercenary armies in the employ of kingdoms that that often go unnamed and whose rivalries just as often go unexplained. We know that the charismatic Griffith wants the throne of Midland for his own, know as well that to achieve this goal requires him to upset the delicate balance of the century-long war with neighboring rival Chuder. What is left out is everything else: what is it that led to this interminable war; what is it that Midland and Chuder are actually vying for; what is the shape of Midland’s politics and ideology; where are the two kingdoms in relationship to one another, let alone to the rest of the world? The few hints we are given of any larger picture -- peeks at legends of the ancient king Gaiseric and his continent-spanning empire, the occasional intrusion by some rogue Apostle come crashing through like a misplaced visitor from some other story -- are only hints, and so only deepen the sense of fragmentation. And if later developments in the story sketch out to some degree the relationship between the various nations of the world and the presiding religious authority of the Holy See, again the specifics are left maddeningly unclear, delivered to Guts, and by proxy us, only by the similarly fallible Serpico from a similarly constrained perspective.

Fitting, given that the literal building blocks of Berserk’s world are likewise of wobbly make and origin: for all that it is easy to admire Miura’s stunningly rendered architecture, his meticulously detailed and endlessly inventive armor designs, and his unwavering attention to the mechanical realities of ships and wagons and weaponry, even modest scrutiny reveals these various elements to be an assemblage of disparate odds-and-ends thrown together with no consideration for their veracity. Miura himself has made no secret of this, clarifying in a 2002 interview that, “if you really talk about technical stuff, you’ll notice that some armors aren’t supposed to be used around that time... I don’t really go that far. I simply like things that look cool,” while remarking in another, earlier conversation that he “created one age that looked like it spanned from the early Middle Ages to the end of the Middle Ages in Europe,” less because he was worried about historical accuracy and more because he “thought the range of [his] imagination might become narrow if [he]... depended on history.” So it goes even with the mythology and cosmology of the series. Exacting though the dissertations young witch Shierke offers on the nature of magic and the metaphysics underpinning the world’s construction are, their implications for Guts and company are almost entirely practical, offering little answer concerning the series’ greatest underlying mysteries, or even deeper questions of just why this world exists at all; it is hardly by accident that Miura has omitted the so-called lost 83rd chapter of the manga, with its introduction to the Idea of Evil (the God of Berserk’s world), from all future reprints for fear that “the appearance of God in the manga conclusively determine[d] its range. I thought that might limit the freedom of the story development...”

If the reader often feels as if adrift in a dream they should at least rest assured they are not alone, for even the denizens of Midland seem struck by the internal incoherence, the irreality of the circumstances and the times they inhabit. “Even now, it feels like one long dream,” observes Casca, Guts’ lover, of her time fighting alongside Griffith; in looking back at his adolescence, Guts cannot help remarking, “It’s uncertain whether it was reality or dream.” “Good dreams, bad dreams; it’s still unfathomable to wake up in the middle of one...” opines Guts’ companion Judeau upon realizing that their desperate bid to restore Griffith to his place as the leader of the Band of the Falcon has come to nothing, a sentiment echoed by Guts’ lieutenant, Gaston, who on his deathbed remarks, “After the victory parties, things always seemed so sad for some reason. Like when I opened my eyes in the morning, it had all up and vanished. That’s how it felt...[like] we got pulled into the middle of some crazy story someone else wrote.” Again and again and again, characters confront the simple impossibility of their being anywhere and anything at all - some, like Guts’ enigmatic benefactor the Skull Knight, even going so far as to echo Gaston’s recognition of the inherent fictionality of their circumstances: “the world is as moonlight reflected on the water’s surface,” he remarks to Guts, later warning the man that the resurrected Griffith “exists beyond the reason of the physical world...[to threaten him] would be akin to someone in a story challenging the one who wrote it.”

The only thing that seems capable of instilling that sense of undeniable immediacy we associate with the actual is violence, brutal and final, the shake or shove from the real world that wakes you from nightmare or blissful dream back to waking and the revelation that what you have endured or enjoyed was nothing at all; at some point Guts even goes so far as to identify all the world as a war, remarking to an admirer who sees in his strength some respite from the nightmare of life how “there’s no paradise for you to escape to. What you’ll find... what’s there... is just a battlefield.” That Miura takes such exquisite, exacting pain to portray the full extent of violence -- eyes popping from heads like candy from piñatas, broken bones jutting from what remains of shredded and severed limbs, detailed dioramas of Guts’ tearing musculature and fracturing skeleton, the better to let readers observe the tremendous physical strain of his confrontation with demonic forces -- simply works to demonstrate that it is pain, battle, the forever looming possibility of a death inescapable and undeniable, that must constitute something like the bedrock of reality. Critics who lambaste Miura for overindulging in his most morbid proclivities might not be entirely wrong when they censure him for toeing too far on the side of bad taste, what with his penchant for graphic depictions of rape and brutalized children, but such accusations only ever seem to have the half of it; equally misled are those who would defend the series from such criticism by insisting that such grizzly depictions are necessary because their grittiness is an accurate reflection of violence and suffering in our own world. They are not, are in fact grossly exaggerated takes on the vulnerabilities of all flesh blown up to such repulsive extremes (where in our world does blood spray in torrential geysers, do teeth and viscera explode from the body to break through outlined panels with a rocket’s force as if insisting on their reality, do we find scenes so perverse as that of Guts standing in a rain of blood and viscera while a skeletal fetus dangles by an umbilical chord from his mouth?) that they become something that must be engaged with, must be acknowledged by readers even if it is only long enough for them to reject it, which in turn only affirms these spectacle’s violent power - affirms, ironically, their reality.

And yet even this violence, which seems both the one unifying principle of Berserk’s plane and its one transcendental truth, seems to have a limit embodied no better than in the Apostles, those monstrous entities lurking in the shadows as the secret chiefs of the world. As almost parodic imitations of life, sporting appearances like cancerous profusions of mundane natural forms (horses, bulls, slugs, snakes, among others) swollen to monstrous extremes and endowed with so great a degree of physical strength that even whole armies often seem helpless before the might of a single one of their kind, the Apostles serve as the ultimate symbols of the grossly physical, as arbiters of what writer Antonio Wolf dubs the “radical finitude... of Nature’s being.” Yet so monstrous are they in strength and brutality and form, so openly do they flout conventional laws of what is possible and appropriate in a world even as horrific as Berserk’s, that their existence seems more a perverse mockery of these certainties than any affirmation of it. In the face of the perfect representation of what seems the sole unifying principle of all the world, binding together royalty as well as commoner, the only thing that might be called real, even battle-hardened veterans who’ve witnessed Hell on Earth and Midland’s most hard-bitten citizens cannot help questioning their senses. “It was terror itself,” thinks a trembling Guts upon first witnessing the Apostle Zodd’s transformation; “It’s like I’ve strayed into someone’s bad dream... it’s like the real world has begun to crack, starting here...” muses the sex worker Luca upon witnessing an exchange between the Skull Knight and an Apostle; the mercenary Corcus can only deliriously cackle “A dream... it must be a dream...!” as hordes of the abominations descend to feast on his comrades.

Of course, it is: everything of this world is a dream, as much an ideological construct as a material construct; it is simply that the characters have so long inhabited their rigid world of literally overpowering material dictates that they cannot help regarding anything that upends their assumed knowledge as fantasy. With all the parallels drawn between life and dreaming, with how often what should be impossible transgresses against the prescribed boundaries of the mundanely possible, perhaps it should not be so great a surprise that there is something fictional to the construction of this world, that the very God of the world is less a naturally occurring and primal force of nature or transcendental entity than a kind of Jungian “Ego of the world,” its origins in the “swells [of collective unconscious]... [that] wanted reasons for the destiny that kept transcending their knowledge.” The apprentice witch Schierke offers her own extended description of the mystical laws that model the world, explaining to Guts that their own world is “overlapped by the existence of two others: the world of spirits, the astral world... [and]the soul of the origin of all existence, [known as] the world of the idea” with her mentor, Flora, further clarifying that “this world could never be summarized by materialism or any single doctrine.” Whatever sense of permanence the plane of base matter seems to have is itself a fiction at the mercy of currents of thought and fantasy: nowhere is this more apparent than in the aptly named “Fantasia” arc, wherein Griffith is able to force a merging of the conceptual realm of the Astral -- where exists all manner of “ethereal beings... living legends” -- with the physical plane, resulting in full-scale invasion of the “real” by the “unreal.” Yet this is not to say that these other realms represent some kind of Platonic ideal, not when the world of ideas itself exists as an extension of the thoughts and feelings of those in the material sphere, equally subject to the thoughts and feelings of its inhabitants. The Idea of Evil is again no all-powerful deity; more a slave to human will than any independent agent, while Griffith’s merging of the conceptual and material worlds is an act born in the material, the narrator describing it explicitly as “mankind’s desire.” In the cosmology of Berserk, there exist no foundational principle: the whole of the world is a dream fed by dreams ushering in only more dreams, a yin and yang of sometimes competing/sometimes converging phenomenologies.

If, at last, the picture this paints is of a work defined by deep contradiction that is precisely because Berserk is a deeply contradictory work, Miura’s epic a story every bit as messy as even Guts’ most brutal battles; the author was always quick to make it clear he was an improviser who “trusted in [his] own carelessness” moreso than any mechanic given to exhaustive planning (a “gardener” rather than an “architect”, to borrow the paradigm fellow epic fantasist George R. R. Martin is given to sorting his peers by). Nor does this messiness extend only so far as the exercise of world building; given that it is established how the various realms of Berserk grow out of and into its characters, how could the people this tale revolves around be anything other than a bundle of paradoxes themselves? Quick as fans and detractors alike are to emphasize the barbarity of Miura’s masterwork, to dwell at length on the beautifully rendered scenes of gruesome conflict that earned Berserk its reputation for shock (a reputation Dark Horse’s obnoxious ad copy has done nothing to dissuade: the synopses on the back of the English volumes again and again paint it as “a runaway manga locomotive [of] taboo-breaking humor that fires the boilers of its devoted devotees and just fires the rest,” and “a bludgeoning manga bulldozer”), what is lost in most popular discourse surrounding the comic is how artfully observed are the psychologies of its cast, how deftly it explores sensitive concepts of desire and fear and loss. Make no mistake, the characters of Berserk are a broken lot, the series for so much of its time a tragedy in which all people, down from peasants up to the pope, seem to have been cursed with the same fundamental flaw: they are forever broken in such a way that they are forbidden knowing what their true desires are until, in a desperate moment beyond any saving, they glimpse from the corner of their eye some objet petit a they have been furtively chasing without ever recognizing it. All grasp that there is something wrong with themselves and with the state of things, and yet can find no solace, no matter how hard they work to sate this existential hunger; something of their pasts has left them forever unable to recognize what is most precious until the moment they realize they cannot grasp it. For all his bluster about being torn between his love for Casca and his wish to avenge himself on Griffith, Guts remains unable to see that he is still raging against the father figure that sold him out and searching desperately for the family he has again and again been denied; for all her vaunted affection for Griffith, Casca realizes only with his departure that it was in fact Guts she loved; and for all his high-minded rhetoric about obtaining his own kingdom, Griffith fails to notice until the moment it condemns him that Guts was never just another pawn but in fact the only person he has ever loved, loved so much it caused him to abandon the one pursuit he had literally sold himself to advance. Again and again this pattern repeats itself, such that Guts’ later entourage consists -- like the lost members of the Band of the Falcon Guts cannot help associating them with -- of people united less out of any great shared values than a communal sense of lack, who sense in Guts’ stalwart façade something of the heedless purpose they all wish they possessed, hearing in Casca’s declaration of love that “licking wounds is good enough” - something like a mission statement for their party. Even the bestial Apostles who are said to have “transcended their very humanity” and for whom “do what thou wilt... [is] the only commandment” are one and all likewise cursed to discover on their deathbeds that what they willed was not at all what they wanted and there is still one thing lacking, that they have wasted their unnaturally prolonged time in pursuit of wanton pleasure at the expense of some obscure dream their demonic nature blinded them to, and so despite their seeming invincibility of mind and body, they are only yet another victim of the irreconcilable conundrums at the heart of any life.

What Miura understands so well, and what lends his magnum opus a magnetism far beyond even that engendered by his spectacular art and his legendary stylistic sensibilities, is that there is no pat way of summarizing the behavior of individuals, let alone effortlessly summarizing the full extent of their characteristics when they have grown in a world that is itself defined by lack and by paradox. If they might sometimes feel inconsistent or beyond understanding, that should be understandable; what else could they be coming from, but where they have? If they often contradict former words or sabotage themselves in the moments of victory, it is only believable within the context of a world that seems itself impossible (dreamlike) and they are themselves so limited (fragile). Detractors are given to complain that, as the series goes on, Miura loses his cynicism as he comes to focus on the antics of what some readers derisively referred to as “Guts’ JRPG party” -- that the near-constant state of horror earlier volumes emphasized retreats before a tonal welter given to placing scenes of slapstick comedy and low-brow antics between or alongside moments of extreme emotional tenderness and personal epiphany -- but even this is the natural outgrowth of characters who are so riven with contradictions; of writing a world that tries, however much it might fail, to accurately portray something of the world’s baffling nature. Miura’s own professed desire was to make of Berserk a story that was “downright shoujo mangaesque,” with all due emphasis on “expressing every feeling powerfully” to better avoid the “contrived... calculated” nature of “manga for men.” To insist that Miura had somehow strayed in his later years by modifying the timbre of the story or suggest he had lost his way by privileging his ever more fanciful artistic constructions over advancing the plot at a commercially acceptable pace is to misunderstand the very core appeal of the story and why it resonated for decades even despite every seeming dead-end and mistake. Per Dark Horse Editor Carl Horn, Berserk was predominantly “an epic of contradictions: beautiful, grotesque, whimsical, cosmic” succeeding not despite but precisely because of this inclusive, expansive nature.

Too often the fantasists’ greatest error is in mistaking a world for its geography, for mistaking verisimilitude of fact -- a well ordered globe, an extensively cataloged glossary, an impeccably kept ledger of logically deducible units of thoughts -- for verisimilitude of feeling, that elusive phenomenon of experiencing a world as an individual. What Miura explores in Berserk, by contrast, is a setting more organic, a confused and impossible turmoil of contradicting elements and influences, of half-sketched ideas and phantom terrains and riven, searching, uncertain people that add up if not to some startling epiphany of “truth” then at least to a distinct way of experiencing reality that captures exquisitely both the horror that arises from living in a world of epistemological uncertainty and the fleeting, irrational but beautiful human gestures we make with that time. It is often easy to forget that for much of human history the only perspectives ever afforded our ancestors came courtesy of the grand narratives, national and historical or religious and philosophical, that sketched the boundaries of the possible - and that these narratives were themselves ever butting up against the limited, contradictory experiences of those who inhabited them, who must have grappled again and again with cognitive dissonance as they tried to chart from their limited perspective a world incomprehensible. Bolstered as we are by a surplus of interconnected informational resources that enable us to pick and choose from a variety of authorities to arrive at the illusion of true mastery, of a bird’s-eye remove, we are similarly prone to forget our own foibles and assume that we have somehow overcome the need for such primitive systems of organization. We have, we tell ourselves, all the facts before us; we have, we tell ourselves, the perspective provided by time and distance to map the lay of the land precisely; we’ve seen the atlas. But this, too, is only a story we tell ourselves, and an unconvincing one at that: no matter how much we might insist on our desire for those epics that seem capable of accounting for every blade of grass and every day from the first calendar until the last, such projects are doomed to repel us, leaving us always hungry for more because they have taken on a project that is both conceptually impossible and philosophically offensive to our instinctual understanding that reality is far, far more than any easy accounting of its physical and temporal components. To perfectly map an environment is to simply recreate it in all of its complexity, something that would only leave us where we started - lost and befuddled, only more deeply so with the addition of new and indistinguishable layers. And so limited by imagination and rules as we are we resort again and again to guides more abstract; we resort to stories. Ideological constructs, beyond physical caprice and the wear of time, they are the framing devices by which we attempt to escape our limited lives, promising a transcendental model for understanding a world that resists any comprehensive summary. The better woven the story the more likely we are to interpret it as the truth of things, and with epics like Berserk, which so brilliantly capture so much of life’s endless conflicts -- conflicts of self, conflicts of a martial nature, conflicts of reason, conflicts of epistemology -- we are all the more likely to acquiesce to its spell: even Miura agreed when told “manga is a medium that could probably contain the whole world.” Little wonder that in his own story it is the very merging of the imaginary with the physical that is identified as the whole of “mankind’s desire.”

Yet even this is most all-consuming of fantasies is fated to reveal itself as nothing but another pipe dream, for just as there exists no universal set which might contain all objects up to and including itself there is no universal story that can allow for the full range of possibilities in all lives and all imaginations. No matter how capacious it appears to be, if such a fantasy is to truly contain all the world it must paradoxically likewise play host to the same deficiencies it is attempting to correct. In all the world and all possible worlds there exists no thing to accomplish such a task, and so it is ironically only nothing -- that lack which exists beyond definition -- that can possibly grant the freedom from paradox that stories falsely promise us. It may be that this is why in a series famous for its impeccable art, its lurid spectacle and its sensitive depiction of human relations, what has longest struck me as the most powerful image is not that of Guts standing under a shower of amniotic fluid as a fetus dangles by its umbilical chord from his mouth, not the atrocities of the Eclipse, not those intensely vulnerable moments where Griffith’s internal monologue betrays his desire for Guts even as he seduces Princess Charolette of Midland, or the sight of Guts and Casca holding each other in a lover’s embrace. No, what stops me breathless each time I revisit it is a two-page spread of the Earth’s merging with the astral realm as viewed from the moon, a cosmic tableau that situates this monumental occasion -- the instant humanity seems poised to escape its limited framework into the one story that transcends all others -- in contrast to the vast, uncaring cosmos in stark reminder of how localized even this supposedly sublime experience is, how paltry from the celestial perspective even the fulfillment of mankind’s collective desire must look. Should ever our world feel unreal, that is because it is unreal: nothing more than a series of conflicting stories adding up to an ephemeral dream we’ve all found ourselves living in, absent consent, and from which we must one day wake to the one thing that tolerates no symbols, no stories, and none of the endless contradictions such stories are heir to: the void.

Perhaps this as well is why we feel so betrayed when the authors of previously intriguing epics reveal themselves to be mere cartographers and why those authors who stall out in perpetual hiatus are so often the butt of jokes about mortality: that George R. R. Martin might actually die before the next installment of his series has become so potent a meme it has actually given rise to betting pools concerning whether or not he’s going to croak before he concludes the saga; for a decade-and-a-half, hacks greeted every announcement of Miura’s latest sabbatical with the same tired crack that a new installment of Idolmaster must have dropped. As much as these delays do elongate the story, lending it a sense of weight via the real-time passage of years, they paradoxically serve as a reminder of what we know instinctively but are afraid to articulate: all tales must end, by the author’s discretion or against it. And so each month that goes by in silence is a passive-aggressive threat, each year that ends with only a fumbling promise that something is coming in some unspecified future leaves us keenly feeling that the utopic promise of this conceit -- that maybe this one story could, as Miura believes, “contain the whole” of our jumbled world -- might have been nothing but a trick all along. And so we come to believe that if the same projects that intrigue us initially with their promise to capture the reality of our own jumbled existence inevitably disappoint us for their failure to keep this vow, they at least might allow us the morbid indulgence of witnessing a world end, and end in exactly the way we always secretly feared it must: not with any great bang but casually, accidentally, so burdened by the weight of contradictions it’s amassed that it keels over in exhaustion even as its overtaxed author collapses from heart attack or from disease or any of one thousand other weaknesses fallible flesh is heir to.

Perhaps this is why we feel so disbelieving and bereft when these authors actually do pass, and the perverse wish to experience the end of the world gives way to the confounding sense that this should not be, could not be. While we knew in our hearts that this outcome was the only possible one because we have seen first hand how all stories some day terminate, we must have hoped we were wrong about at least this one, whereby its spark of rare genius suggested the author had managed to contain something of the timeless and ineffable. Hence why the endless jokes about the author’s coming death are always hitched to hopes for the immortality of their work. We bet on Martin’s death while speculating on whether, like his peer Robert Jordan, he might have designated a successor to usher his work to completion; we joked about the impossibility of Miura’s death by situating it within a story all its own, insisting it would be us on our deathbeds waiting for news about how Berserk was developing, hoping that this fictional world we put so much stock by and dwelt in for so many years would outlive our own, and in so doing contain some bit of what we’ve left behind. Still others insist against all sense that these untimely conclusions are in fact satisfactory. That Miura, contrary to all expectation, did deliver something like the happy ending he once hoped for. It hardly matters, they say, what was to come of Griffith’s ambitions when Casca’s mind had been restored and she and Guts reunited, and that Guts’ companions had begun to resolve their respective traumas; the good have been rewarded the just deserts of a loving found family while the monstrous languish at the heart of their corrupt dream, a kingdom at a false peace built at opinnumerable sacrifices. As assertions go it is patently ludicrous -- Guts’ and Casca’s situation had hardly concluded on a romantic note, with the two of them still too traumatized even to greet each other face to face, while it is clear that Griffith’s machinations were to have inescapable ramifications for all the world -- but if ludicrous, it is also understandable: just as we find solace in hoping that these stories offer a parallel life which me might escape into and so offer the promise of quasi-immortality, when confronted with the brute reality of their demise and all it portends for us, we find similar comfort in the idea all stories must end they might at least do so tidily, happily.

We know, of course, that they will not, cannot. That Miura was unable to achieve the impossible should hardly be misconstrued as some kind of deception on his part. Not, at least, as a malign one. He must have known in later years that at his current pace and with his late-life preference for ever more baroque compositions that Berserk’s completion was, if not impossible, at least a vanishingly slim possibility. The work’s ambition had only ever seemed to increase; its scope only ever to widen even as it continued, while Miura's own propensities -- if not his talent, which was as prodigious as ever -- sputtered and stalled. And yet he persisted on in trying to capture something of a fantasy which might have capacity enough to contain the world, both in its gorgeous art and its narrative. Like his creation Guts, a man who is constantly identified as “the struggler” for his tenacity in the face of his inevitable end, Miura was tirelessly dedicated to a project that he must have realized on some level was a fool’s errand. That he failed to bring it to any but the most unsatisfying possible conclusion is coincidentally and ironically the most appropriate ending all projects so ambitious might have, capturing even to the last something of the anticlimax of what it is to live in a world that we are forever trying to understand as anything more than the transient dream it is, roused awake by some rude hand.

* * *

I came to Berserk some 17 years ago, fully half my lifetime, at the recommendation of a new acquaintance just as a change in schools had isolated me from my childhood cohort and a prepubescent love of high fantasy had curdled into resentment. Where once these tales had offered me something like a high vantage point from which to view a larger world that felt so distant, they now seemed -- as the classic and modernist literature I was discovering revealed new aesthetic and moral possibilities for art, and my estrangement from people emphasized a social atomization I’d never known before -- the kind of escape taken up by people who were so afraid to admit to their shortcomings and ugliness that they would gladly tolerate what struck me as pandering. At first glance Berserk seemed the same: how else to interpret a story that opened with a man shoving a grotesquely phallic cannon into a succubus’ mouth before splattering her brains across the country side of some nondescript European setting? But the acquaintance was promising, my isolation paralyzing, and I was eager to make common ground with others even if it meant sacrificing something of my literary standards.

What I would never have predicted is that Berserk would prove an instrumental text for uniting a larger friend group, a codex that enabled us to talk as openly our camaraderie, our fears of death, our anxieties concerning love and vulnerability, as about grand metaphysical concepts like fate and causality and our general apprehensions about religion, or that in the following two decades I would perpetually revisit the series in some piecemeal fashion, either working back through arcs when I felt their major thematic concerns were relevant to my life, when I wanted to refresh myself in preparation for the release of latest volume, or dipping into certain scenes and arcs because of a nostalgic yearning to experience again those emotions that had once felt so raw and urgent. In preparing myself to intercept the more gruesome aspects of the comic, I’d left unguarded my emotional vulnerabilities, and was unprepared to find a series that spoke directly to all matters concerning the vagaries of the human heart. At a period when I was coming to understand how little I truly knew even about myself, while trying desperately to bridge a confusion of social relationships, I was heartened to find that Miura’s characters acted in ways that likewise often eluded their critical faculties and left them helpless as much to the currents of some obvious Freudian subconscious as to deeper psychological streams and eddies that compelled them on to ends they often became aware of too late. Despite their air of martial invincibility or collected command, they were often weak, limited souls who only occasionally found fleeting chance for salvation in each other, a sentiment I felt all too keenly as I began to grapple seriously for the first time with my own limitations. Never before had I had a group of friends so close as the ones I made in those years, and consequently, never before had I great cause to wrestle with the complex of emotions that arose in such demanding relationships. As in the best of all fiction, it felt to me as if there was something at work in Berserk of the real, some element of life that Miura in his rare artistic genius had managed to crystalize despite all the contradictory limits of fictionality. In the close-knit companionship of the Falcon I found a model for the selflessness and the unconditional support that would prove instrumental in paying proper respect to my most vital friendships; in the anguish of Griffith’s pining for Guts I identified and named for the first time those similar and frightening feelings I had developed for someone similarly precious. Even the way the manga reflected global events, so full of violence and menace and injustice and institutional corruption, seemed accurate to my own slowing-growing awareness concerning of history and contemporary events. What I found in Berserk, in short, was a story by which I could explain the world.

As is the case with all such models, Berserk’s use as an explanatory text has changed over time, waxed and waned and morphed even as I have. Yet it has been for so long such an important work of art -- a work those old friends and I even now discuss -- that I had come to take its existence as much for granted as I might have gravity. To hear that Miura had died and that Berserk would conclude prematurely was not unlike hearing that the tides had stopped; that he should die within a day of losing the last of my grandparents and in a year that saw the suicide of one of my closest friends, the death of the last of my parents’ pets -- a dog I had helped raised and train -- and the utter devastation of my hometown by no less than four world-class climate catastrophes, only heightened the realization that such loss was no aberration but in fact the natural order of things. Berserk was a story I told myself for over half my life, one which seemed to have, if not the capacity to explain all of life, then at least to adjust so neatly to developments in my own understanding and worldview that it seemed a close enough proxy; and yet it was not flexible, not large enough to contain that greatest of all contradictions.

There is a moment at the end of Berserk’s Golden Age arc that has haunted me for years, just after the remaining Band of the Falcon have discovered that Griffith’s year of imprisonment has left him permanently broken -- tongue ripped out, tendons all severed, his famous beauty vanished under a welter of scars and burns -- and scant hours before he plunges them into the hell of the Eclipse. They stand at the edge of Midland’s territory, in the middle of a near-empty and seemingly endless steppe, wind blowing through the grass, setting sun hanging permanently in mid-descent: one has the sense that they have stumbled into some liminal borderland that marks the boundary not between nations, but between the collapse of one dream and the hope for another, as evocative a symbol of melancholy as I have ever encountered. As they convene to discuss their options, and if, maybe, Guts might not lead them in Griffith’s place, there is the faint sense of possibility that marks every new chapter in life: the hope that these all losses can be redeemed. Yet deeper still and all-pervasive is a sense of foreboding that assures us this is not the case. Readers know that the horrific future depicted in Berserk’s first three volumes -- Guts, alone, insane, condemned to spend his life locked in combat with demons -- must come to pass; we have long enough heard the imprecations of Apostles who warn the Band that “when [Griffith’s] ambitions collapse, death will pay you a visit! A death you can never escape,” to understand this was no hallucination. Prophecy and narrative construction have both dictated that history can only end one way, and yet in a moment of weakness readers must hope there are alternatives the characters have not yet seen. Even Casca seems to implore the audience to hope as she begs Guts to remember that “everyone’s weak, and so they rely on dreams....” Desperate as this situation is, she seems to say, Guts might still inspire his comrades by providing them a new story around which they can rally, a reimagined narrative of who they are and where they are going. Maybe, too, the audience might find in this imprecation to belief a new story that diverges from what we thought we knew, not merely about Berserk, but more largely about life. “Stories,” she is saying, and as Miura seemed to be saying without his oeuvre, are ultimately all we have.

I am afraid all we have is not enough.