In recent years some of the most obscure (not to mention neglected and deserving) vintage newspaper strips have been lovingly resurrected, often in the form of elaborately wrought book-objects. I’m thinking of some of the Sunday Press titles, the Herbert Crowley monograph from Beehive Books and a few others I thought I’d never live to see. While I have mixed feelings about the often imposing packaging, this is a very good thing (although I can’t begin to fathom the economics of it.) And then there are other approaches…

In recent years some of the most obscure (not to mention neglected and deserving) vintage newspaper strips have been lovingly resurrected, often in the form of elaborately wrought book-objects. I’m thinking of some of the Sunday Press titles, the Herbert Crowley monograph from Beehive Books and a few others I thought I’d never live to see. While I have mixed feelings about the often imposing packaging, this is a very good thing (although I can’t begin to fathom the economics of it.) And then there are other approaches…

The idea for gathering a collection of Cecil Jensen's Elmo had been a deep back-burner fantasy project of my own since I was introduced to this funny, perverse strip back in the 1980s (public tip of the hat to my ex-boss at Topps, Len Brown of Mars Attacks fame.) A strip like Elmo weaves that kind of spell, you read it and you feel compelled to share it with the world. Frank M. Young has recently taken Elmo on as nothing less than a personal mission and I’m eternally grateful (and I can finally scratch this one off my list.)

Chances are you have never even heard of Elmo. If that is the case, Frank logged a couple of TCJ columns on the work last year which you can access here and here,which serve as excellent introductions.

I chatted with Frank about how this project manifested, his decision to self-publish, but mostly about Elmo itself (which Frank has dubbed “An American Experiment”) a comic strip that is genuinely addictive (and still makes me laff out loud.)

Mark Newgarden: For years I felt like Elmo was a private hallucination of mine. It made little sense to me that a strip as dark and funny and risky as this one could have been neglected for so long, especially in a publishing climate where many far more pedestrian strips are given the turnstile “classic” reprint treatment. How and when did you discover Elmo?

Mark Newgarden: For years I felt like Elmo was a private hallucination of mine. It made little sense to me that a strip as dark and funny and risky as this one could have been neglected for so long, especially in a publishing climate where many far more pedestrian strips are given the turnstile “classic” reprint treatment. How and when did you discover Elmo?

Frank M. Young: In 1977, via the microfilm newspaper archives at Florida State University in my hometown of Tallahassee, FL.

With little info on comics history, and few reprints, Strozier Library’s microfilm collection was a welcome portal into all the history I could take in. The first eight months of Elmo was among my first discoveries. Elmo intrigued me right away. It was funny, yet not funny. The humor sometimes took days to register with me. I read all I could, and Elmo joined my general pool of arcane comics knowledge.

Fill us in on Cecil Jensen’s background and the forces that helped shape this strip.

Cecil Jensen was born in Ogden, Utah in 1902. Ogden was still a wild Western town at the time, with an underground den of vice beneath its main streets. Jensen’s first cartoons ran in his hometown paper during the first world war. At age 21, his first syndicated strip, Tied for Life, lasted eight months. Jensen moved to Los Angeles in 1924 to work as an editorial cartoonist. He moved to Chicago in ’28 and drew editorials until he died in a retirement home in ’74.

Jensen considered his editorial cartoons his major work. In his papers at the University of Syracuse, there’s correspondence and original art—but only for the editorials. Nothing on Elmo or his other strips.

His editorial cartoons from the 1940s shows that he was ready to do a strip like Elmo. In his cartoon “There Will Be Complications at the War Criminals’ Trial,” a roomful of Adolf Hitlers stands before a judge. It proves its own theory: one Hitler is horrifying; a roomful is hilarious. It shows that Jensen could find humor in all the wrong places.

Elmo didn’t click with the public. At a glance, there seems to be nothing happening in the strip. But once you give it your attention: wham!

Elmo didn’t click with the public. At a glance, there seems to be nothing happening in the strip. But once you give it your attention: wham!

Elmo lasted less than two years. By summer 1948, a kid character named Debbie elbowed Elmo out of the strip. Re-named Little Debbie in spring 1949, the strip continued to the end of September 1961. In its final year, Jensen brought Elmo and his world back for a few months of sudden inspiration. The strip became so disturbing that his syndicate’s flagship paper dropped it in mid-week. That’s chutzpah—to do a strip so tough its own syndicate won’t run it!

Then Elmo petered out again. Jensen didn’t seem to know where to go with it. He ended Debbie in a bittersweet coda that satirized Charles Schulz’s Peanuts and created one of the few genuine endings in comic-strip history.

The strip never set the world on fire. At its peak, it was in maybe 50 newspapers.

The best things never last. Where Elmo was modeled on Lil’ Abner (and to my mind greatly improved upon it) the more popular Little Debbie (which I think you like more than I do) seemed to take square aim at Nancy and fall utterly flat. Tell me where I’m wrong.

I have learned to like Little Debbie. At its best, it retains the sinister humor of Elmo. Jensen had inspired streaks, but I think he felt obligated to continue the strip, and sometimes it feels like a slog.

To me, Jensen was just not well suited for a traditional gag strip, especially one often dependent on visual gags.

His best humor is verbal. Take the dialogue away and its just people in an office. The character relationships are great, the stakes are solid, but everything is under the surface. Elmo makes you pay attention and unravel its moments.

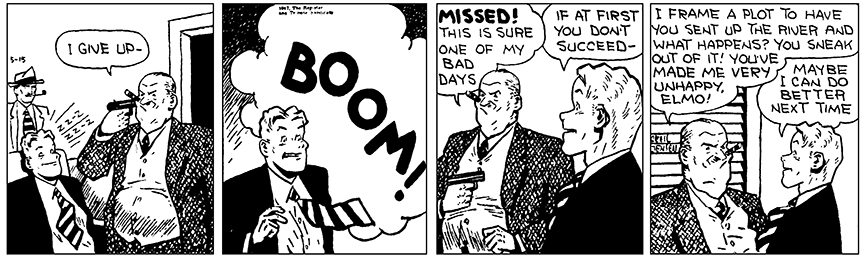

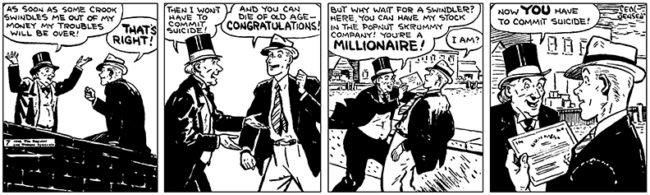

Jensen could do visual humor, as in this strip, where the impact depends on the reveal in the last panel:

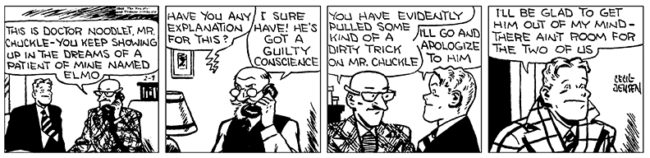

And this one, where the staging of events gives us an un-nerving mix of noir drama and black comedy:

The art’s musty old-school vibe helps undersell the humor. Elmo dares you to laugh—and to figure out why you laughed.

Elmo seems to belong to a certain strain of dry deadpan mid-century humor that I hold dear. This includes things like Vic and Sade, Bob and Ray, perhaps even the Herbie comic book as you mentioned in one of your TCJ essays. A lot of the technique is wrapped up in the seemingly mundane, earnest delivery of aggressively peculiar (or even perverse) material. The results can be subversive - but quietly and slyly subversive. Can you talk a little about this dialectic in Elmo?

The humor is like a delayed-action pill. You swallow it, and five hours later it hits you. Elmo has caused me to laugh out loud in the checkout line when a bit suddenly makes sense.

We’re used to a quick payoff in humor. You see the bit, you laugh, and it’s done in three seconds. Elmo, like Bob and Ray, plays with a dead pan and goes for a long-term relationship with your brain.

Jensen’s humor is a mix of old-school corn and mid-century cool. The friction of those elements makes Elmo (and Debbie, at its best) go different places. That aspect and the strip’s violence made its original audience uneasy. It’s not obviously a gag strip or a story strip. It’s almost never broad or loud. It doesn’t beg you to like it.

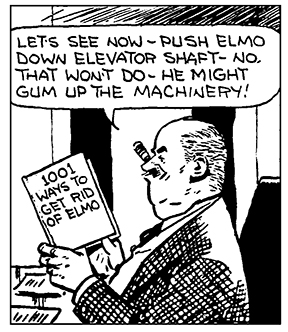

I love that Commodore Bluster has a custom-made hardcover book titled 1001 Ways to Get Rid of Elmo. It provokes a chain of unseen events. Who wrote the book? How did they compile the information? What printer made and bound this single copy? What’s the index like? That’s hours of speculation for the reader in a throwaway moment. Other comic strips don’t deliver this effect.

I love that Commodore Bluster has a custom-made hardcover book titled 1001 Ways to Get Rid of Elmo. It provokes a chain of unseen events. Who wrote the book? How did they compile the information? What printer made and bound this single copy? What’s the index like? That’s hours of speculation for the reader in a throwaway moment. Other comic strips don’t deliver this effect.

The strip has a strong sexual vibe. One of its main characters is a stripper, and voluptuous women throw themselves at Elmo, who seems asexual.

Late in the strip’s first run, Elmo sings a song over the radio with a chorus of quacking sounds. The radio waves zap migrating ducks in their rears—goosing them, if you will with an implication of sexual congress. And there are strong Amazonian women—almost like some of R. Crumb’s sex fantasies! It’s seamier and more “underground” than other strips of the day. You read Elmo and wonder who green-lighted it. I’m glad they did, but it’s jarringly dark and adult.

There is a sequence where Elmo goes to a psychiatrist because he wants to know why a bearded man keeps showing up in his dreams - so the psychiatrist calls up the bearded man and demands to know why he keeps showing up in Elmo’s dreams. Pure Jensen. What other cartoonist thinks that way?

None living.

Can you tell us a bit about how this book came to be? It has a few notable aspects. This is a self-published print-on-demand production. Why that route? Did you pitch it to the likely suspects? If not, why not? To me this project should have been a no-brainer for any of them.

Can you tell us a bit about how this book came to be? It has a few notable aspects. This is a self-published print-on-demand production. Why that route? Did you pitch it to the likely suspects? If not, why not? To me this project should have been a no-brainer for any of them.

This project was occupational therapy for me. I was diagnosed with leukemia and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in late 2016. I was in and out of the hospital for three years and underwent two stem-cell transplants. The second one seems to be sticking; I’m eight months out and cancer-free.

During recovery, I needed a project. And then I found Elmo while on Newspapers.com. Across several papers, the whole run was there. I found and bought a fair number of newsprint dailies. The rest came from the better examples on that website.

Having that self-imposed work schedule gave me purpose. I didn’t tell anyone I was working on it until I was on the home stretch. I feared someone else would announce they were publishing it. But I was alone in this effort.

The restoration of the strip was done in three full passes over two years’ time. Early on, I decided to self-publish. I have several books available through Amazon’s KDP print-on-demand service, including four books on cartoonist John Stanley. I like POD because it doesn’t waste resources. There are only as many copies of Elmo as the world desires. They don’t take up warehouse space. If I discover errors, I can pull the book for 24-48 hours, fix the mistakes, and put it back on the market.

With the Adobe programs, I had the same tools as a designer or editor at one of the publishing houses. The book didn’t need to be done by committee. I solicited feedback from friends and colleagues as I worked through the restoration. The quality of KDP’s printing and paper has improved, and I feel the book compares favorably to anything from Fantagraphics or other independents.

Most importantly, I get royalties from every copy printed and sold. That didn’t happen with either of the graphic novels I co-created with David Lasky. It hasn’t happened on any book I’ve published through traditional channels. The economic structure of traditional publishing seems, to me, built on the promise of failure. If a book receives critical acclaim but isn’t properly promoted, it still fails in the marketplace. The publisher gets the kudos of a critical success (including, in our case, an Eisner Award for The Carter Family: Don’t Forget this Song) and can declare a loss on the book, which gives them a tax write-off. It’s a time-tested business strategy that means most authors don’t get anything beyond the advance they receive at signing. The thousands of hours those two graphic novels required made the advance equal to a living wage from 1939.

The Art Young anthology that I co-edited with Glenn Bray required a group effort. Fantagraphics’ designers did a knock-out job. I was paid for my essay but not for the editorial work, which took about three years. I knew that going in.

The Art Young anthology that I co-edited with Glenn Bray required a group effort. Fantagraphics’ designers did a knock-out job. I was paid for my essay but not for the editorial work, which took about three years. I knew that going in.

The Elmo project could be a one-man show. I had a window of time to do the work, and it was important to me. Elmo was shafted by its syndicate, the newspapers that subscribed to it and its reading public. I felt that it needed another chance.

I thought about approaching an established publisher with the project. But the odds were stacked against me making anything from those two years of work. That’s not why I did it, but I feel that my effort is worth something. Low printing costs enable me to affordably price the book and realize a decent per-book royalty. Even if the book only sells a thousand copies, I still get paid for every one of them.

I also felt that it might be too out-there and obscure for most publishers. Elmo is a hard sell, but it’s not a multi-year epic.

What’s next for Frank Young?

I am working on a second volume, which will capture that final year of Debbie and offer a selection of the in-between years of the strip.

I’m looking for better source material. The only sources I have for the ‘60s strips are terrible looking. It will take twice the work of the first book. If anyone out there has clippings from the Lincoln, Nebraska Journal-Star, Chicago Daily News, Seattle Times or the New Orleans Times-Picayune, please get in touch with me. Those are four papers that carried the strip to its final episode.

Mark Newgarden is a cartoonist and co-author (with Paul Karasik) of the Eisner-winning How To Read Nancy. He teaches at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and the Parsons School of Design in Manhattan.