Full disclosure: Brian Blomerth has been a friend of mine since I lived with him for a few months a decade ago. Fuller disclosure: His work has nonetheless been pretty baffling to me, on a level of “I’m not really sure why he does this.” I can understand people who are obsessed with depicting violence and sex, people nostalgic for their childhoods, people making constant jokes in order to be liked, etc., but the main ingredients of Blomerth’s art, the dog-faced people and weird decorative flourishes, seem to come from a place completely beyond what I can access from my vantage point, situated in normal reality, and observing causal relationships between events and how they get processed into art. While his work is distinctively his, there’s nothing about it that would be traditionally understood as “personal” in a way that might lead someone who knows him personally to be biased in its favor.

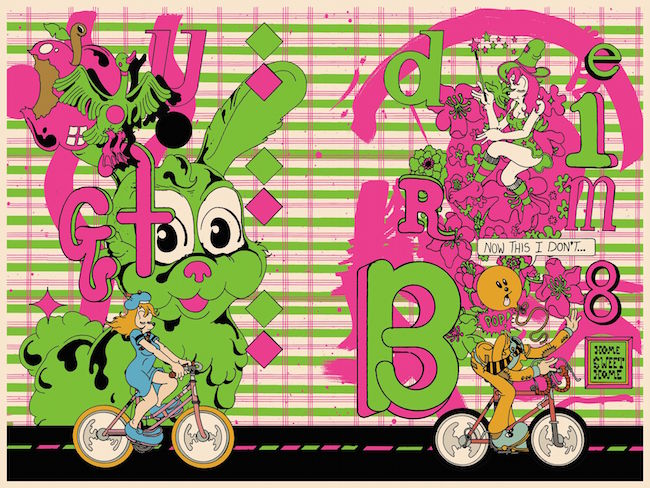

Also, over the past few years I’ve seen, from the distance of Instagram, Blomerth’s profile rise, and I do not think he needs me advocating on his behalf. If anything, my understanding of his work, clouded with the baggage of personal association, detracts from how far his work has been able to travel without being associated with him. His audience is different than my understanding of a “comics audience,” and that social media and doing a strips for Vice and a website about weed has led to an abundance of illustration work for bands and earned him an audience of people willing to shell out for expensive t-shirts. He has graduated to the realm of doing posters for bands who make, absolutely, some of the worst music I have ever heard. When I first met Blomerth, his visual art would’ve been most visible on the J-cards for the self-released cassettes of his noise project, Narwhalz (Of Sound). Those pieces were collages of different colored paper, each of which were drawn on. I took it in the way I viewed the visual art of Brian Chippendale on a Lightning Bolt album cover, where the bright colors pressed against one another served as an analog to the music within, and while the visual art might be less abrasive for not being loud and therefore overwhelming, it still served as a warning. Since then, the profile of the visual art has grown and been placed into different contexts, and I’ve realized that despite the abrasive and transgressive aspects of Blomerth’s personality, there is a broad audience that simply likes the way his stuff looks, especially with the more sophisticated color sense he now achieves using Photoshop.

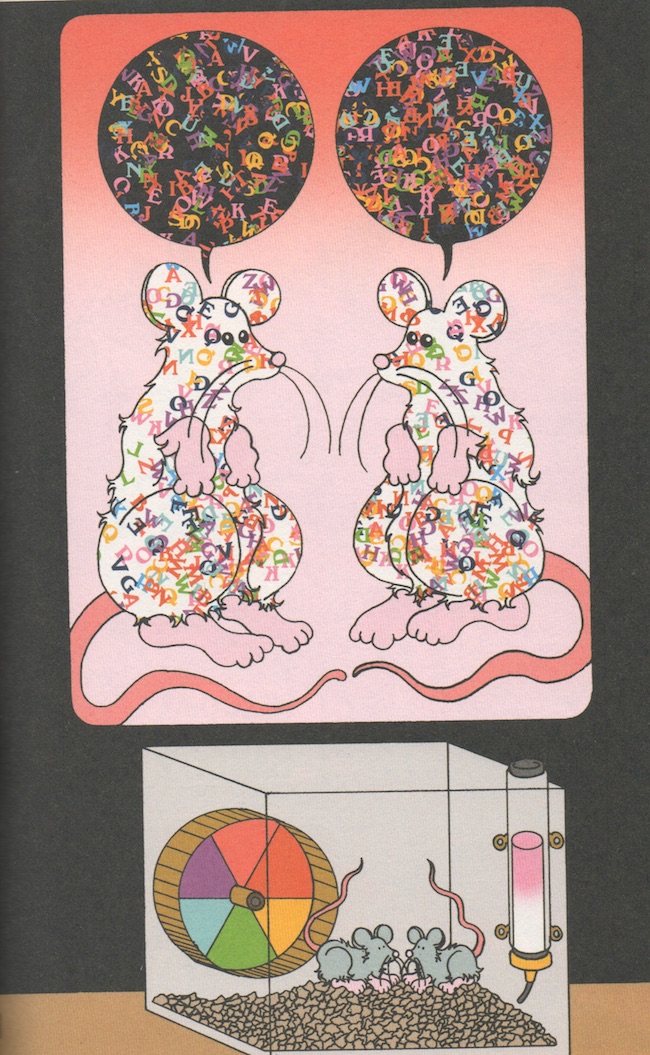

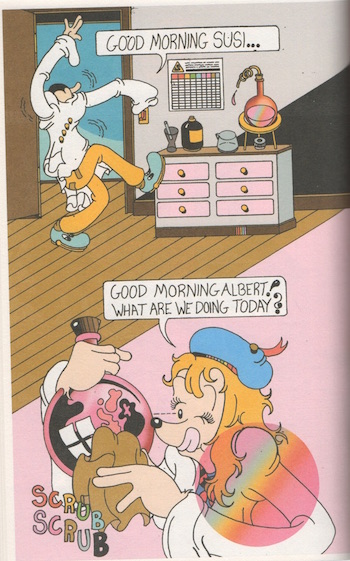

This culminates, at least for the moment, with the publication of Bicycle Day, a graphic novel about the Swiss chemist Albert Hofmanns’ discovery of LSD. Published by Anthology Editions, a book publishing imprint of a record label, I was surprised to find multiple copies for sale in a suburban New Jersey Barnes And Noble. I thought of them as a small publisher, and didn’t expect them to have that kind of reach, but I can see how them going big might be rewarded, and the book itself is, I think, really good. While many nonfiction comics come out with a sort of “hook” that seems designed for quick write-ups in gift-giving guides which is then pitched to a specific interest, Bicycle Day works as something a person would buy for themselves after giving it a quick once-over. It’s immediately visually gripping, and reading it provides enough context for it to feel like a satisfying read. In an afterword, Blomerth describes the book as an experimental children’s book, and while it’s close to 200 pages long, it’s composed as a series of spreads, all of which withstand the scrutiny of a sustained gaze. The acid trip sequences present new approaches to reality morphing with every page turn, but the vision of a cartoon Switzerland populated with cute animals blends nicely with it, and the whole book walks the line between the openly psychedelic and the cartoon-cute, appealing on both levels simultaneously. Form matches content in an interesting way: Considering the intensity of psychedelics when they’re actually ingested, any fictional depiction of them is sanitized to the point of being a Disney version. The story itself is incredibly simple, as Blomerth expands on what Hofmann devoted a few pages of his biography to, expanding the page count to book-length like some sort of comics narrative equivalent to time dilation.

This culminates, at least for the moment, with the publication of Bicycle Day, a graphic novel about the Swiss chemist Albert Hofmanns’ discovery of LSD. Published by Anthology Editions, a book publishing imprint of a record label, I was surprised to find multiple copies for sale in a suburban New Jersey Barnes And Noble. I thought of them as a small publisher, and didn’t expect them to have that kind of reach, but I can see how them going big might be rewarded, and the book itself is, I think, really good. While many nonfiction comics come out with a sort of “hook” that seems designed for quick write-ups in gift-giving guides which is then pitched to a specific interest, Bicycle Day works as something a person would buy for themselves after giving it a quick once-over. It’s immediately visually gripping, and reading it provides enough context for it to feel like a satisfying read. In an afterword, Blomerth describes the book as an experimental children’s book, and while it’s close to 200 pages long, it’s composed as a series of spreads, all of which withstand the scrutiny of a sustained gaze. The acid trip sequences present new approaches to reality morphing with every page turn, but the vision of a cartoon Switzerland populated with cute animals blends nicely with it, and the whole book walks the line between the openly psychedelic and the cartoon-cute, appealing on both levels simultaneously. Form matches content in an interesting way: Considering the intensity of psychedelics when they’re actually ingested, any fictional depiction of them is sanitized to the point of being a Disney version. The story itself is incredibly simple, as Blomerth expands on what Hofmann devoted a few pages of his biography to, expanding the page count to book-length like some sort of comics narrative equivalent to time dilation.

A moment can grow inside the head of the person experiencing it to feel an eternity, and the person experiencing it can feel there will never be another to follow it. When I met up with Blomerth in his Brooklyn apartment, he told me he approached Bicycle Day as if it were the only book he might ever get to make. This is fairly reasonable, as the future is unwritten and anything can happen or not happen, but now that it’s out, it seems to be doing pretty well. I’d heard that Bicycle Day is the best-selling book ever at the Brooklyn comic shop Desert Island. I called Desert Island to confirm and the answer was “Yeah. I’ve sold like 75 copies. We might’ve sold more copies of Watchmen, over ten years, but that’s it. That says something about the book, and something about the crowd that comes here.” When I called, Blomerth’s book would’ve been out for a little over a month and a half.

This is surprising to me because it does not seem that long ago that the combination of elements that made up Blomerth’s work struck me as fairly alienating or confrontational. Many comics people, perusing stuff at small press shows, were surely put off by the fact that everyone is depicted as a dog. While he’s getting illustration work now, he’s not budging on that point. “Lots of clients are fucked because it has to be a dog.” He’s not drawing humans anytime soon, either in his comics or for illustration work. “I like being connected to the funny animal genre,” and if people are hiring him, that’s what they’re going to get. I left the interview with a plastic cup advertising an event at Union Pool, sponsored by liquor companies, with four of Blomerth’s characters frolicking in front of a cityscape.

I imagine both comics fans and brands would avoid depictions of dog-people due to the association with furries. However, despite the fact that Blomerth depicts his dog-women as “sexy” there still doesn’t seem to be a furry fanbase picking up on his work the way they’re attracted to corporate mascots like Tony The Tiger and Chester Cheetah. The only reason I can think of for this discrepancy would be that Blomerth’s male characters aren’t depicted as strong and muscular; they frequently give off the impression as being nebbishes, suggesting the sort of comedy dynamic between sexualized women and overwhelmed hapless men you’d see in old Playboy cartoons, or Beetle Bailey. While he said it was “funnier to keep it G-rated these days,” he also said a friend of his suggested that while his characters don’t have sex on-panel, they do off-panel, and it’s completely disgusting, and Blomerth laughed with the sort of approval that suggests this interpretation is now canonical.

Back when Blomerth did draw explicit sex, it was very obvious that his work was in the lineage of underground comics. This is still heavily implied by his new book being about LSD, but while I am sure he didn’t learn about drugs from comics, he did learn something about sex from undergrounds. To hear him tell it, there was a Robert Crumb comic, found in an anthology at the library, that introduced him to the idea of semen. “What is this white stuff?” he remembers thinking, though now he doesn’t know what book exactly it would’ve been that contained what he describes as “a Crumb comic about business people fuckin’ the world. There was a lot of cum.” He knows it wasn’t the Bill Blackbeard Smithsonian collection, which he also looked at a lot. What would’ve been there were Floyd Gottfredson Mickey Mouse strips, which were clearly influential, and were read alongside Carl Barks reprints. I also see a strong Victor Moscoso influence on Blomerth's work. Blomerth liked underground comics but did not have much access to them. What would’ve been accessible were newspaper comics. When he tells me he still likes Berkeley Breathed, I can see the kinship between them as well. Learning to draw from copying newspaper comics left lingering effects. “Sometimes I’ll draw a hand like this,” he says, bending his hand at the wrist with the fingers backward, “and it’s the Fox Trot hand.”

Lately he’s been hearing comparisons to Joost Swarte, who he has since checked out. He thinks the similarity just comes from Blomerth using a ruler to draw straight lines. Blomerth’s approach is to draw everything freehand except for manmade objects like architecture, which he uses a T-squares and templates to handle. To him, his work looks like the Disney stuff he grew up on, but, he says “I’ve been rereading Barks’ stuff, and it doesn’t really look like that either!”

A more important disclosure is that Blomerth lies a lot, and I have a bad track record for credulity. When he Photoshopped an image of Kanye West wearing a “Sexy Pepsi” t-shirt, and captioned it “Guess I should make more of these” I totally thought it was plausible Kanye would wear a t-shirt with a sexy dog-woman Blomerth drew on it, but, upon further consideration, it is not.

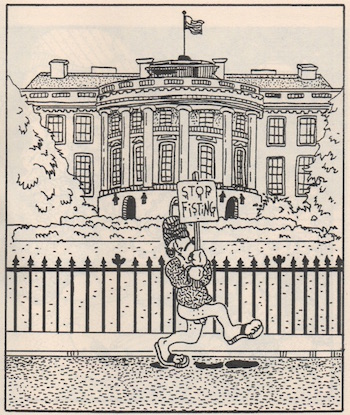

When he released a minicomic called The Book Of Worzil, which he labeled as “rejected New Yorker cartoons,” it seemed plausible that the rejection letter from Bob Mankoff at the end was authentic, even though my initial thought had been that there was no reason why he would’ve ever submitted them in the first place. On further consideration it seemed plausible he could’ve done so for his own amusement and the rejection letter would then be real, an accidental byproduct of the process it would then make sense to include. Still, I’m sure it’s not real.

Writing a Consumer Reports column for artnews, he writes “Lies are my favorite form of media. Especially, ones that you get called out for immediately.” It’s worth noting that the people who are closest to him do this as well, and that somehow over the years a weird and elaborate mythos has emerged through all of them based on ridiculous lies not getting called out and so developing into genuine misconceptions.

“I’ll hear something or think something and believe it’s real,” he admits. A recurring theme when I talked to him more frequently would be stories he would tell about celebrities I had never heard before, that seemed distinctly apocryphal, as if he was the only one who’d ever heard them. These stories would be like: My Bloody Valentine took forever to make their third album because Kevin Shields got really into ferret breeding, and the ferrets would run around the studio, chewing on wires and shitting everywhere to the consternation of the rest of the band. He also once told me Steve Martin once did a performance at a college where he got in a swimming pool, tried to drown himself, but every time he surfaced would shout out “Still alive!” at the audience. When I insist I don’t believe these things happened, his response is “Why would you deny the chillest shit?”

While every celebrity becomes in some way a mythic figure, the stories Blomerth told are at odds with the myths of those people as I understand them. They move away from the elements of control and perfectionism that are widely promulgated perhaps because they play into American notions of “hard work” explaining how celebrity status is earned and attained, instead embracing chaotic notions of self-destructive idiocy that present a more confusing alternative. It is maybe this misunderstanding of myths that’s important to understand when looking at Blomerth’s decision-making process, a lot of which may look like self-sabotaging or masochistic.

Take, for instance, the decision a few years back to make a comic about vaping. Understanding Nicotine coincided with Blomerth’s selling a line of vape juices called Slippy Syrup and purported to be the theories of a Japanese scientist, Ispib Osnotkitchi. However it carried a legal disclaimer explicitly stating it was fiction: “By purchasing this book you agree that the publisher maintains this book is false.” In the comic Blomerth drew, the scientist was, of course, depicted as a dog, though the commercial advertising the comic had an actor playing the role. While being bummed to concede the point that all this was an obvious lie, Blomerth then showed me a trailer to a martial-arts movie the actor had written and directed.

The comic also had a passage that asserted Walt Disney injected liquid nicotine before he died. These are fictions — lies — but the formal language of the comic is one of “nonfiction comics,” a riff on Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, and it’s able to move in a way that is both entertaining even as it feels informative and well-researched. It probably was well-researched, (in Baltimore, Blomerth mainly made money as a human guinea pig in smoking studies, and was in fact injected with liquid nicotine) but all to the end of conveying disinformation. I’m not going to argue that an artist’s creative decisions should be decided by what the market desires, but I will say it was a truly baffling comic to read and try to imagine who it might be for. “Jeff Foxworthy says you gotta entertain yourself,” he says, and what amuses Blomerth is these sort of conceptual hijinx, moreso than actual jokes with punchlines.

When I asked if his comics are funny, he expressed ambivalence, and wondered how many comics are actually funny. He then listed the Paper Rad and Simon Hanselmann as some of the few. When I suggest that what holds up about comics is that they’re well-drawn more than funny, he says “I agree 1000%.” He views the heart of his comics as being their drawing, which leads to a desire to distance himself from older work. This is both due to his drawing now being better than it used to be, but there’s also the sort of embarrassment typical for a man his age (Blomerth is 35) over what he did in his twenties when he just wants to calm down and avoid doing things that may be self-sabotaging. The desire now is for “just a nice quiet life and not have everybody mad at me.” Still, Slippy Syrup was, for a time, profitable, and even got mentioned in the New York Times after being namedropped as part of someone else’s prank. Such victories essentially affirm the sort of narratives Blomerth ascribes to Steve Martin or Kevin Shields: Like the fox in Antichrist says, chaos reigns.

Such prankish behavior seemingly determined the decision, since reversed, for his comics to regularly feature explicit sex, moreso than any gratification he got out of it. I did ask the question we’re all thinking: Did he jack off to his drawings of masturbating dog-women in estrus? The answer was no, and I don’t think he’s lying about this. “Fun to draw for sure, but I’m not a Crumb-style raging-boner monster. Not knocking it though.”

But: vaping, lies, funny animals, explicit sex or its absence: The choice of these elements is value neutral, indifferent to conventional ideas of aesthetics or morality, that combined together make for something confusing but compelling. In his newer work, this skill manifests on a level of image composition rather than a narrative one. The spreads in Bicycle Day might short-circuit the brain, but to be dumbfounded in such a way has a name for it, and it’s beauty.

This is not to say I don’t still suspect him of lying. In the afterword to Bicycle Day, he explains that the book’s dedication to Richard Scarry is based on an apocryphal story that the children’s book author was obsessed with Switzerland and drove his family insane by talking about it so much before he’d ever visited. I pressed him on this and he said he read about in an interview with Scarry’s son, also a children’s book illustrator, and there were photos was wearing Swiss fashions. The Scarry dedication also functions as an acknowledgment of the formal similarities Bicycle Day has to children’s books. These sort of conceptual interests, in the formal qualities of a project, are what keep him interested now, with the choice of subject matter owing to a desire to dive into technical drawing.

I mention I like the spread with all the calligraphy on it, and Blomerth tells me he had wanted his previous comic, Xak’s Wax, to feature way more calligraphy than it actually did. He enthuses about calligraphy, saying he wanted to develop it as a hobby inside his comics, but then says that’s insane: “You can’t have a hobby within a hobby.” He points out that both technical drawing and calligraphy, and the tools you use to achieve them, are “things you should learn in art school, but never do,” explaining how you can achieve the calligraphy on the cover of Manly P Hall’s Secret Teachings Of All Ages with a 45 nib, but the combination of technical information and fast-talking enthusiasm overwhelmed my ability to transcribe.

I mention I like the spread with all the calligraphy on it, and Blomerth tells me he had wanted his previous comic, Xak’s Wax, to feature way more calligraphy than it actually did. He enthuses about calligraphy, saying he wanted to develop it as a hobby inside his comics, but then says that’s insane: “You can’t have a hobby within a hobby.” He points out that both technical drawing and calligraphy, and the tools you use to achieve them, are “things you should learn in art school, but never do,” explaining how you can achieve the calligraphy on the cover of Manly P Hall’s Secret Teachings Of All Ages with a 45 nib, but the combination of technical information and fast-talking enthusiasm overwhelmed my ability to transcribe.

There are aspects of drawing and comics he wants to explore, like drawing more panels on a page, but when I say I think he did that well with a comic called Hypermaze, he dismisses it. “In my mind I just started doing comics with the Vice thing but I know that’s not true.” That was in 2016, and while having his comics in full color shifted the visual emphasis of his work, and so changed his storytelling away from the obviously underground-indebted, to me the continuum with his older work remains clear, and improvement’s been steady, but not exponential. Ten years ago, he was working on The Small Dog Other, a tabloid-size underground about violent biker pomeranians, when he switched from Microns to a Rapidograph and his line immediately became much smoother. “I love that motherfucker,” he says, proceeding to calling it a “fun-ass pen.” Then, as now, he drew straight to ink without preliminary pencils first, but, he points out, then he did not realize he could use Wite-Out to make corrections. He says this was good, as it forced him to learn to draw, but he now uses Wite-Out constantly. “I’m a Wite-Out baby.” I’m unclear on when he figured it out: Hypermaze was the followup to that, but it was preceded by a small 16-page preview zine, almost all the pages of which were completely redrawn for the larger print-run publication. At the time, he viewed it as the beginning to what would be a several-hundred page epic, though he now says that the drawing in it is bad and he will not return to it, and that he wants to list it as “Sold Out” on his website despite still having many copies.

The Small Dog Other is listed at his website as his first full-length comic, but at a mutual friend’s house, I have in passing seen work that predated this. These zines would just have one character talking in a series of borderless panels on each page, and Blomerth describes these as “Paper Rad ripoff shit.” He’s aware that in the future he will likely feel as critically towards his current work as he now feels about this older material. “In ten years I’ll be like this shit sucks.”

“Yeah that’s a terrible drawing,” he laughs about an album cover for the band Videohippos, which I recall for the scale of the original art, a work on paper that probably needed an entire gallery wall to be hung on before being photographed. That, I suppose, would’ve been done when Blomerth studied painting at Virginia Commonwealth University, because college grants time for such indulgences. Now, as Blomerth works on a solo issue of Smoke Signal, the balance between keeping the drawing interesting and the amount of time he can reasonably devote to it are in conflict. He likes the look of large drawings reduced down, so he is drawing what will be printed at 11 by 17 at a larger scale than that. Still, there’s an issue of how time consuming this could potentially be. “I can’t do 3-4 days on every page.”

The amount of time spent drawing Bicycle Day was much less than you would imagine. Anthology Editions originally suggested just doing a collection of Blomerth’s Vice strip, Alphabet Junction, which would’ve taken a lot less time. Starting from scratch led to spending a month on research, then doing the first 70 pages in a span of 3 months, before getting a phone call explaining the book was due. The rest of the book’s 188 pages were done in a month and a half, what Blomerth calls a “nightmare run” of 18-hour days, during which he did no other illustration work, which he has since resumed. The result of working so hard on such an insane deadline is he now views his art as looking much better now than it did on the Vice strips. This would be another part of the masochism I ascribed to Blomerth earlier: He does enjoy the punishment being a full-time artist subjects him to in order to subsist.

He also thinks it’s nice that his follow-up to a thirty-dollar book will be an issue of Smoke Signal that will be given away for free. Legally, giving his next comic away for free will be the only way it can be published, because Blomerth has wanted to tell a story, seemingly for a while, about the Grateful Dead bears, who are under copyright. Something that’s free protects him and his publisher, and connects to the Grateful Dead ethos that similarly allowed for the tape trading of show bootlegs. I don’t want to say anything here that can be considered an endorsement of the Grateful Dead. When I begin to hint I might begin talking shit, Blomerth says “I like that they’re not for everybody.”

Despite the Grateful Dead comic, his biweekly strip on a website about weed called Merry Jane, and doing a booklength comic about the first time anyone did acid, it shouldn’t be assumed the cartoonist himself is a big participant in drug culture. Having known Blomerth for a while, and reading his comics, I would instead suggest that he himself shares similarities with LSD: There’s an outward colorful demeanor, that can shade into the demonic, but if you can make peace with that, you can come back to the brightness and joy. I don't intend to evangelize. I feel about his work the way Albert Hofmann did about what he called his “problem child:” It should be researched and investigated.